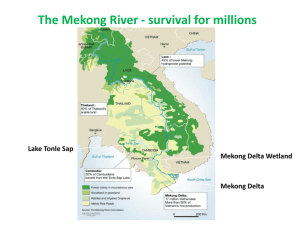

D. Use of local knowledge in the study of river fisheries

advertisement