MOBILE COMPUTER BASED CLASSROOM IN EARTHQUAKE

advertisement

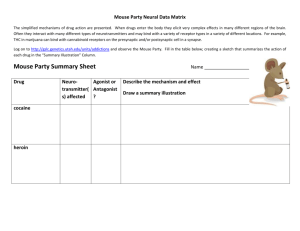

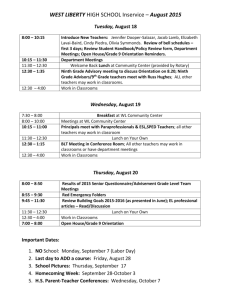

MOBILE COMPUTER BASED CLASSROOM IN EARTHQUAKE REGIONS OF TURKEY: A UNIQUE DISTANCE EDUCATION EXPERIENCE Yavuz AKPINAR, Erol INELMEN, Avadis HACINLIYAN, Ayþe CANER Boðaziçi University Faculty of Education Istanbul, Turkey akpinar@boun.edu.tr A1167 Abstract: This study reports a unique type of cooperation between a state university, a non-governmental organization (NGO) and a private company to provide "supportive instruction" to students experienced an earthquake disaster. The project, UMUT2000, aimed to provide support education to students in poor environmental and school conditions with the help of technologically rich instructional settings so that the students without hope for the future can be introduced to the facilities of modern classrooms, individualized new experiences and can change their vision of the world. The paper describes implementation and application of the mobile computer based classroom project, and reports some classroom observations. Keywords: mobile classroom, supportive instruction, computer based instruction INTRODUCTION The text, graphics, sound and digital data processing capabilities of computers have been rapidly developing. Similarly data access and data reading speeds of CDROM devices have increased every month. Transferring varying types of data such as sound and text and merging them into a coherent application is no longer problematic, but an ordinary activity for any information technology user. Beside, such revisions and enrichments in communication technologies, computer networks and the Internet are getting wider realization. Computers at the same or different sites are linked to each other to communicate data graphics and text; hence creating distributed electronic work environments. These network of computers are classified under two particular names local area network (LAN) and wide area network (WAN) on the basis of locality. Within the LAN and WAN type networks, a multi-cast information source is obtained. Different multimedia resources, databases, statistical, mathematical and other packages can be accessed and utilized for desired needs. For example, engineering students can logon to simulations and video packages at different locations, economy students can access to large and continuously updated databases and graphics packages in order to test, interpret and extrapolate all sorts of data. Sharing and exchanging data and software packages are so common that as if Bush’s (1945) utopia of “paperless office” is achieved. The network tools for speedy access to information patterns are continuously improved. Since late 1980s, e-mail, Telnet and ftp type of environments have been supported by systems as Gopher, WAIS and WWW. Whilst these systems are becoming more appropriate and more cost-effective in terms of security, ease-of-use and rapid access (Debrecency et al, 1995), their usage by institutions and individuals are among daily activities. For instance, in schools and colleges, computer networks as LAN and WAN are now commonly used, some schools share software packages and data. Also, discussions about different learning and teaching strategies are done in electronic discussion lists, data banks are shared and electronic help facilities are explored (Akpýnar, 1995a and Chee, 1995). Further, storage and analysis of such packages within the same environment make these systems more advantageous. Therefore, individuals at different sites can easily cooperate to be more productive and can increase product quality to a large extent. Along with developments in information technology, improvements in the quality of human resources are still getting considerable attention from societies. When developments of human qualities are considered, learning environments are to be inevitably examined. Computer technologies have an outstanding potential to be employed for improving human qualities. Although hardware is getting cheaper and more versatile, software problems do still exist worldwide. It has been accepted that when computer technology is “appropriately” used for learning a particular subject, most students can learn the subject provided that all conditions of learning is also met (Kozma, 1991). Hence individuals receiving distance education (DE) service should not only study courses with TV, radio and printed materials but also study with animations, multimedia environments and other interactive learning software. In brief, every educational institution should seriously and systematically consider “appropriate software” matters. DE institutions also face software problems for classrooms. The problems originated from the nature of distant learning are to be tackled by both the software designer and all other concerned authorities (McGiven, 1994; Tiffin & Rajasingham, 1995; and Parker, 1997). Main source of the software problems is in two fold; firstly, the software is not able to meet distant students’ needs, and secondly the distant learner may not fulfill the requirements of studying with the software. Much distant education software does not possess a proper help unit, which will aid the learner whenever he needs any sort of assistance. Due to lack of software facilities to guide the learner or due to late access to such guidance, effectiveness of the software is likely to be minimized. As in intelligent tutoring systems (Wenger, 1987), DE software needs components able to understand the student’s actions and accordingly organize the software activities for him. Because building a student model and programming intelligent educational courseware are problematic procedures (Akpýnar, 1995b), DE software should have student support features additional to the features of software used under teachers’ monitoring in classrooms. In preparing DE software, computer managed communication and network technologies could be considered in a way that some support mechanisms can be integrated into the software to be used by distant students. Such mechanisms will enable the software and the student to communicate with DE authorities. This, in turn, will empower the learning process to be more productive. Computer assisted instruction was first introduced to Turkey in the mid 1980’s. At that time, the main activity was teaching programming using primarily the BASIC programming language on Commodore or Atari type home computers (Hacýnlýyan & Tepehan, 1991). Inadequate integration into the other parts of the curriculum, inadequate efforts spent in teacher training and in creating instructional material have always been the weak points of these attempts of introducing technology. In spite of the fact that PC compatible modern hardware and software has been introduced, the fundamental point that an educational system, like all other computer systems, is a man-machine integration has been overlooked. The same is also true for the recent attempts in introducing the Internet to the educational system. Consequently, the educational needs of students are not always being properly addressed. Adequate educational material in the Turkish language through online facilities, books or other material is lacking because of such unexpected and undesired phenomena. Under certain conditions such as an earthquake the students in those regions require an entirely different service and approach. For example they need attention, respect, love and consideration after shocking experiences. Quickness in action emphasis on mass education in large volumes with high quality may become necessary. A UNIQUE DISTANCE EDUCATION EXPERIENCE On 17th August 1999, a destructive earthquake occurred in the Marmara region of Turkey. People lost many relatives, children lost families. Thousands of property including school buildings became ruins. When the school term began, in many of the affected provinces school children could not find buildings that were safe enough to permit schooling. Tents inevitably became schools. However such temporary and improper shelters couldn't meet educational requirements. A state university, a nongovernmental organization (NGO) and a private company collaborated to give "supportive instruction" to those students, in compulsory schooling age 7-15, in the earthquake areas. The project, UMUT2000, aimed to provide support education to students in poor environmental and school conditions with the help of technologically rich instructional settings so that the students without hope for the future can be introduced to the facilities of modern classrooms, individualized new experiences and can change their vision of the world. Three large transportation buses were converted into high-tech mobile classrooms; two of the buses were redesigned to be mobile classrooms involving computer and multimedia technologies and one of them was redesigned as a mobile school library and a game room. Care was taken in order to make the busses self-contained and functional under the adverse conditions that would prevail in a deprived area. The facilities of one of the mobile classroom are: 19 Intel Pentium III 450-550 KHz multimedia computers (one to be used as a server and 18 PCs as client stations), 15" monitors, A laser and a DeskJet color printer, A scanner, A photocopying device, A projection device, A large screen TV, A video player, A video camera, A hub, A surround sound system, A white board, A projection screen, A satellite dish to connect to the Internet, A power generator and a UPS. The second mobile classroom has the same facilities with 12 computers. Both mobile classrooms had computer based learning software that support the school curricula. The faculty of education of the university specified the hardware configuration and layout of the internal design of the buses. Preparation of the mobile classrooms lasted about five weeks. The commercial company sponsored the project as part of its New Year advertisement campaign. It covered cost of all expenses of these three buses, including hardware, software, allowances and equipment maintenances. The NGO took responsibility of one of the mobile classrooms with 12 computers and the mobile library, and the university took the responsibility of running the other mobile classroom. Both the university and the NGO run their services in the areas ruined by a recent earthquake, but their services did not go to the same schools. This paper will give details of how the university managed its responsibilities of carrying out education support in those ruined area schools. UMUT2000 Mobile Education Center Four departments of the Faculty of Education were actively involved in the project. While the mobile classroom was being prepared, the departments specified and searched for adequate types of software suiting their needs and the school curriculum. After the procurement of the software and laying out a plan of how many and which schools (sites) to be served, the service began. Both the planning and the actual execution of the project was done with the close collaboration of the Ministry of Education authorities in the three affected provinces, Kocaeli, Sakarya and Yalova. The project was placed under the responsibility of a Faculty appointed coordinator. As the faculty and its staff is located in Istanbul, a 100-180 km distance to the sites, and as the faculty members have other duties to do, it was decided that the mobile classroom stays in a different site every week and the faculty members travel to those sites with a different vehicle. One school of education lecturer with one research assistant, three assisting students both graduate and/or undergraduate and a technician comprised the education team. Every day a different team was formed. Their schedule was clarified a month forward. In order not to interrupt the school teachers' work, the schools were informed about the visit at the beginning of the projects, along with other authorities such as Ministry of Education and Local Education Secretaries. The teaching hours were kept in parallel to lesson period of the schools. The service for first two days of the week was undertaken by the department of computers and instructional technology, teaching students about introductory computer skills; components of a PC, basic of working with a commonly used operating system, Windows 98, (file, folder, mouse actions and other interface basics), computers as calculators, applications including paint, MS Word basics, multimedia and the Internet. Since number of students in the schools visited was much larger than expected (the number of students rapidly increased in those schools as the families returned their home or shelters gradually), in some of the schools the Internet instruction couldn't be completed. In third and fourth days of the week, teams from the mathematics and science education departments, respectively, visited the school and provided computer based support to students at mathematical and science domains at which most students experience learning problems and develop misconceptions. Finally on the fifth day, the foreign language teaching department provided computer based support to students at English language domains at which most students experience learning problems. All the teams gave support to 108-144 students in a day. LESSONS LEARNED As mentioned above, the first two days of the educational support activities of the project was aimed at acquainting students with computers as a tool for learning. A teaching program that would include introduction to various Windows tools was envisaged. Students ranging from 9 to 16 years were expected to attend the classes in groups of 18. At the time of planning the program for the project, it was decided to use the Windows Tour as an introduction to the use of computers. It was soon found that this tour did not motivate the students. Many of the students were too slow in adapting themselves to reading the material and doing the necessary manipulation on the keyboard and mouse. Furthermore, they were not achieving a product that would interest them. A decision was thus made to drop this part of the program, as the activities involved were more appropriate for a higher age group. Students found themselves more comfortable when using MS Word –the popular text processing program- as a tool for writing their basic personal information. They were asked to write their names, teacher’s name, school and courses taken. Two different versions of exercises were used, depending on age group of the target audience. Using large font sizes and capital letters only was found to be more convenient for the youngest students. The use of various colors in the text made the text more appealing. In the alternative approach, different font sizes, capital and small letters were used and an attempt was made to instruct the students in the use of the keyboard. Older students enjoyed this and, in some cases, were able to perform drag-drop operations. Including clips from the programs own files proved not to be very easy and the practice had to be used sparingly. This part of the program lasted about 20 minutes. In the second part of the program that also lasted for 20 minutes the Paint program was used. In the first weeks the students were requested first to draw something and then paint it. It was soon discovered that drawing using the mouse was not an easy task so that a pre-drawn figure was selected for painting only. Many students were able to complete the task before the time allocated so the introduction of the spraying tool was added to create the idea of snow in the given landscape. Some students even had time to paint some extra figures that were drawn by the teachers. After finishing this exercise, students were asked to open the Windows calculator, use the numeric keypad to enter two numbers and divide them. The implementation of the program soon showed where the bottlenecks were. Students had difficulties in differentiating the “blank”, “enter” “shift”, “caps lock”, “num lock” and “backspace” keys, so some preliminary explanations had to be given using a keyboard. Even more complex was the learning of the correct handling and use of the mouse. With the three keys, the mouse proved to be difficult to use considering that the hands of the students were far smaller than then device. The relatively small space available for moving the mouse in the relatively cramped space of the bus was another difficulty. Preliminary explanation of mouse use and restricting mouse operations to those involving the left hand key enhanced the learning process. It was necessary to show the way that the ball inside the mouse worked, since some students took the mouse on their hands to operate it. Many students also lacked the dexterity involved in double clicking the mouse. Instruction on the multimedia and multitasking capabilities of the computer was restricted to asking students to put on earphones, minimize the Paint software, double click an approximately three-minute long MIDI file involving popular Turkish music, reactivate Paint and continue with the painting exercise. The staff sometimes allowed students that showed exceptional progress to play games and thus rewarded them. Although students seemed not always interested in listening to the preliminary explanations about the use of the keyboard and the mouse, the practice was continued because it helped the staff to communicate with the students and get their first reactions. Many students showed interest in continuing the practice when a computer would be available. Some expressed their desire to request their parents the purchase of a home computer. The possibility of playing games with a computer was a major concern among male students CONCLUSION The students were so much intrigued with the mobile classroom and their teachers were also interested to see the facilities and some asked the authorities to obtain such facilities for their schools. The service may therefore be approached as a part of inservice teacher training. In many cases, the classroom teachers were encouraged to participate in the activities. The students were so motivated that they did not leave the mobile classroom, their teachers frequently indicated that the students pay more attention to classroom activities after they have the mobile classroom experiences, the students started to ask more questions in the classroom, the students' attendance frequency to schools increased, the students started to talk about the mobile classroom facilities rather than repeatedly talking about the earthquake experience. This mobile computer based classroom experience has been extremely interesting and rewarding from technological, sociological and educational points of view. Technologically, it has been demonstrated that a mobile educational unit involving high technology computing, telecommunication and multimedia equipment can be put together and made functional in a relatively short time and it would involve high but not exorbitant costs. Furthermore, it has also been able to operate under heavy workloads with very few failures and maintenance requirements in deprived and disaster affected regions. Virtually all failures have been associated with the motor vehicle and not with the educational equipment. Finally, the system has been maintained with relatively few personnel. Authorities should consider using such equipment in rural and sparsely populated provinces as an alternative to procuring technological equipment to every school. Sociologically, the affected area was one of the highest income tax-paying regions of Turkey before the disaster and it has been an interesting to observe the extent of deterioration that had been caused directly and indirectly by the disaster and its effects on the students and staff of the schools. A public service has also been rendered to the students and teachers in the area. This has caused a significant morale boost. Educationally, the experience has been extremely revealing from the points of view of developing suitable material for a relatively diverse age group varying from childhood to early adolescence. The extent of participation by the administration and class teachers of the host school has varied from school to school and has greatly affected the effectiveness of the program. Student response has been in general favorable and enthusiastic. REFERENCES Akpýnar, Y. (1995a) Internet for Collaborating Teachers: Preparing Curriculum Tasks for Interactive Learning Environments. Proceedings of ED-MEDIA 95, [Edited by H. Maurer] 733-734, Graz, Austria, AACE Akpýnar, Y. (1995b) Examining the Design Principles of ILEs. Proceedings of ICCE 95, [Edited by D. Jonassen & G. McGalla] 298-307, Singapore, AACE Akpýnar, Y. & Hartley, J. R. (1996) Designing Interactive Learning Environments. Journal of Computer Assisted Learning, V. 12(1), pp. 33-46 Bush. V. (1945) As We May Think. The Atlantic Montly, 1(1), 3-10 Chee, Y. S. (1995) Mind Bridges: A Distributed Multimedia Learning Environment to Support Collaborative Knowledge Construction. Proceedings of ED-MEDIA 95, [Edited by H. Maurer] 292-298, Graz, Austria, AACE Debrecency, R., Ellis, A. & Chua, K. (1995) The Integration of Networked Learning Delivery: from Strategy to Implementation. Proceedings of ED-MEDIA 95, [Edited by H. Maurer] 340-345, Graz, Austria, AACE Hacýnlýyan, A and Tepehan, G. (1991) Language Problem in Secondary School Instruction Involving Computers. Turkish Journal of Physics, 15(2), 217-224 Kozma, R. B. (1991) Learning with Media. Review of Educational Research, 61(2), 179-211 McGiven, J. (1994) Designing the Learning Environment to Meet the Needs of Distant Students. Journal of Technology and Learning, 27(2), 52-57 Parker, A. (1997) A Distance Education How-to Manual: Recommendations from the Field. AACE Educational Technology Review, No.8, 7-10 Tiffin, J. and Rajasingham, L. (1995) In Search of the Virtual Class. Routledge, NewYork, USA Wenger, E. (1987) Artificial Intelligence and Tutoring Systems. Morgan Kaufmann, Los Altos, USA