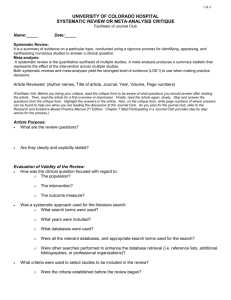

intervention conducting

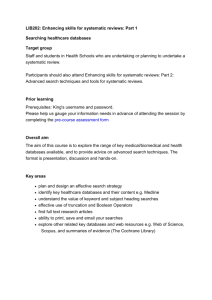

advertisement