Minimum marriage age laws and child marriage in Africa Minimum

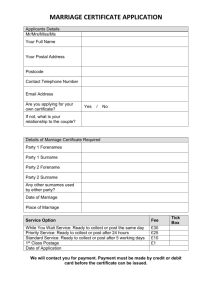

advertisement

Minimum marriage age laws, child marriage rates and adolescent birth: Evidence from Sub-Saharan Africa Abstract This paper examines associations between minimum marriage age laws, child marriage rates and adolescent birth in 12 countries in sub-Saharan Africa (SSA). Two data sources are used: the Demographic and Health Surveys (DHS) from each country and the Child Marriage Database created by the Maternal and Child Health Equity (MACHEquity) research program at McGill University. The paper first assesses whether there is an association between consistent minimum marriage age laws of 18 years or older for girls and child marriage rates; and secondly, whether there is an association between consistent minimum marriage age laws of 18 years or older for girls and adolescent birth rates. Law consistency refers to where the general minimum marriage age, the minimum marriage age with parental consent and the age of sexual consent for girls, were all set at 18 years or older. Using multivariable models with robust standard errors to account for household clustering, we controlled for poverty, educational attainment, religion and rural or urban location. Holding these factors constant, the prevalence of child marriage and giving birth as an adolescent were 40 percent [prevalence ratio (PR) = 0.60, 95% confidence interval (95% CI) = 0.55 – 0.66] and 25 percent (PR= 0.75, 95% CI = 0.73 – 0.78) lower, respectively, in countries with consistent minimum marriage age laws of 18 years or over compared to countries with inconsistent laws. While still to be confirmed by quasi-experimental analyses, the results are consistent with the hypothesis that marriage laws protect against the exploitation of girls. KEYWORDS: ADOLESCENT HEALTH, MARRIAGE POLICY, EARLY MARRIAGE, TEENAGE PREGNANCY, CHILDREN, ADOLESCENT MOTHER Minimum marriage age laws and child marriage in Africa 1. Introduction Child marriage is widely acknowledged as a harmful socio-cultural practice that is both a cause and outcome of human rights violations.1,2 Defined as marriage or cohabitation before the age of 18 years old,3,4 child marriage undermines a girl’s ability to exercise her right to autonomy, live a life free from violence or coercion and it compromises her right to education. 1,2,5 There is often explicit acknowledgement that the marriage is expected to result in childbirth.5,6 Thus child marriage also permits sexual exploitation under the guise of marriage and places a girl’s health at risk. Additionally, children of adolescent mothers start life at a disadvantage thus perpetuating a cycle of poverty and relative deprivation.5 Two main conventions aim to protect children in Sub-Saharan Africa (SSA), namely Article 1 of the 1989 United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child (CRC) and Article 21(2) of the 1990 African Charter on the Rights and Welfare of the Child (ACRWC). All African countries except for Somalia have ratified the CRC, which describes several child rights violated by child marriage, without expressly referring to child marriage.7 African countries were however underrepresented in the CRC drafting process and felt the need for a regional convention that complements the CRC, while addressing the specific realities of African children.8 The ACRWC thus emphasizes that signatories need to take effective action to end child marriage, set the minimum age of marriage at 18 years and make the registration of all marriages compulsory.9 As of January 2014, all African Union member countries had signed the ACRWCa, though seven have yet to ratify it.9 a Countries that have signed but not ratified the ACRWC are: Central African Republic, Democratic Republic of Congo, Sahrawi Arab Democratic Republic, Somalia, Sao Tome and Principe, South Sudan and Tunisia. Sudan and Egypt ratified with Page 1 of 29 Minimum marriage age laws and child marriage in Africa The majority of SSA countries are, in principle, legally bound by the terms of these agreements. In practice, political will to change marriage laws varies considerably and efforts have been largely inconsistent. For example, 37 out of 41 SSA countries (90%) have nationally legislated minimum marriage ages of 18 years or older for girls.b However, 12 of these 37 countries allow marriage before age 18 with parental consent, allowing parents to marry off their daughters as a matter of course.c Furthermore, almost all SSA countries have exceptions allowing children to marry under customary law or other circumstances (such as pregnancy), without specifying an absolute minimum age for these marriages. Inconsistent legal proscription is problematic because child marriage in Sub-Saharan Africa has been practiced for generations and is still seen as a culturally legitimate way of protecting girls.2,10 In addition, factors contributing to the demand and supply of child brides continue to plague the region such as poverty, high fertility rates, poor educational opportunities, gender roles and economic shocks from unemployment or HIV/AIDS.6,10,11 Consequently, poor parents with limited resources may have financial incentives for marrying girl children early, as the costs of raising and educating girls are weighed against the immediate promise of dowry. Allowing child marriage with parental consent and other exceptions may thus provide official sanctioning of a harmful custom. Setting clear and consistent laws against child marriage may be the first reservations and do not consider themselves bound by Article 21(2) regarding child marriage. Botswana does not consider itself bound by Article 2 that defines a child as ‘every human being below the age of 18 years.’ b Four SSA countries do not have national minimum marriage ages of 18 or over: Cameroon, Chad, Mali and Sudan. The eight SSA countries that are not captured in the 2012 MACHEquity child marriage policy database are: Botswana, Cape Verde, Djibouti, Eritrea, Mauritius, Réunion South Sudan and Seychelles. c Countries with a national minimum marriage age of 18 or over and a parental consent age of less than 18 are (parental consent age in parentheses): Burkina Faso (17) Gabon (15) Kenya (16) Malawi (16) Mozambique (16) Niger (15) Sao Tome & Principe (14) Senegal (16) Swaziland (16) Tanzania (15) Zambia (16) Zimbabwe (16). Page 2 of 29 Minimum marriage age laws and child marriage in Africa step in curbing the practice and possibly improving key population dynamics in sub-Saharan Africa. A substantial and growing body of empirical evidence reveals clear associations between child marriage, adolescent birth and various maternal and child health outcomes. Girls who marry before the age of 18 years are more likely to have children as adolescents.10-14 Moreover, adolescent childbirth is associated with serious obstetric outcomes relative to adult childbearing.15-18 For instance, compared to women over the age of 20, girls giving birth between the ages of 10 and 14 years are five to seven times more likely to die from child birth, and girls giving birth between the ages of 15 and 19 years are twice as likely.19 It bears repeating that the vast majority of adolescent births in sub-Saharan Africa occur within a marriage or union. Children of adolescent mothers also have poorer outcomes compared to older mothers, including lower birth weights, higher neonatal mortality rates, higher morbidity, stunting and mortality rates.16,20-23 Marriage before the age of 18 years is also an important determinant of women’s reproductive behaviour and health; compared to those who marry after age 18, child marriage is associated with a greater proportion of multiple unwanted pregnancies, higher total fertility rates, obstetric fistula, increased exposure to intimate partner violence and higher HIV prevalence rates. 6,18,24-31 Additionally, Clark et al.29 found that mean spousal age differences are higher among women who married as children relative to those who married as adults. This may constrain their ability to negotiate with their husbands and may also compromise control over their own reproductive health. In other words, child marriage adds ‘another layer of vulnerability’ over and above background characteristics associated with adolescent childbirth, such as lower education, poverty and living in rural areas.26 Page 3 of 29 Minimum marriage age laws and child marriage in Africa The literature reviewed shows that studies of child marriage mostly focus on South Asia resulting in little empirical evidence about sub-Saharan Africa. This is a significant oversight given the disproportionate burden of child marriage in the region. A United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF) report on child marriage found that 46% of 15–24-year-olds in South Asia were married before they reached 18, compared to 37% of 15 to 24-year-olds in sub-Saharan Africa.32 However, 15 of the 20 most affected countries are in sub-Saharan Africa (Table I). In Niger for example, three quarters of 20 to 24 year olds were married before the age of 18.32 In other words, sub-Saharan African countries have some of the highest rates of girl child marriage in the world but have been neglected from rigorous research on child marriage. [Insert Table I] There is global consensus on the importance of setting minimum marriage laws at 18 years, as well as substantial evidence of the link between child marriage, adolescent birth and reproductive health. Yet to the best of our knowledge, there are no studies that examine child marriage from a policy perspective. This study will thus make a much needed contribution to the literature by examining the association between minimum marriage age laws, child marriage and adolescent birth in Sub-Saharan Africa. The severe reproductive health and infant morbidity concerns exacerbated by child marriage and adolescent birth increase the need for analysis of prevention efforts, particularly those centered on marriage laws. 2. Sample We merged information from two sources: the Demographic and Health Survey (DHS) and the Child Marriage Database. The DHS is funded by the United States Agency for International Development (USAID) in order to provide low- and middle-income countries with data needed Page 4 of 29 Minimum marriage age laws and child marriage in Africa to monitor and evaluate population, health and nutrition programs on a regular basis. This paper focused on responses to the DHS women’s questionnaire which collects information about socioeconomic characteristics, reproductive history, maternity care, sexual activity and contraceptive use. Health histories and anthropometric data are also collected for children younger than five years of age.33 The longitudinal Child Marriage Database was created by McGill University’s MACHEquityd research program for 121 low- and middle-income countries currently included in the Demographic Household Surveys (DHS) and Multiple Indicator Cluster Surveys (MICS) by UNICEF. The Child Marriage Database, created through a systematic review of marriage legislation, civil codes and child protection legislation from 1995 to 2012, includes such indicators as: the legal minimum age for marriage as well as various exceptions permitting marriage at younger ages. Information is captured for both girls and boys, which allows for the analysis of gender inequalities in marriage laws. The study is limited to girls because child marriage affects more girls than boys and because many of the health risks are specific to girls, such as those arising from adolescent birth.5 The data source for the age of sexual consent is the Family Online Safety Institute’s (FOSI) Global Resource and Information Directorye (GRID). FOSI is an international non-profit focusing on comprehensive research of the issues, challenges and risks facing children online. GRID is an up-to-date source providing data and information on online safety, e-learning and country laws on sexual offenses, children and the use of the Internet in the commission of criminal activity. d e http://machequity.com/ http://www.fosigrid.org/africa/africa-edition#profile [date accessed: 2 February 2015] Page 5 of 29 Minimum marriage age laws and child marriage in Africa Analyses were restricted to the most recent (2010-2012) DHS women’s datasets for sub-Saharan African countries, using 2009 child marriage policy data to better approximate a cross-sectional dataset. Additionally, the sample was restricted to women aged 15 years to 26 years as this age cohort was more likely to have grown up in the global anti-child marriage era, signified by the 1989 Convention on the Rights of the Child (CRC) and Article 21(2) of the 1990 African Charter on the Rights and Welfare of the Child (ACRWC). The countries and survey years examined were: Burkina Faso (2010), Burundi (2010), Cameroon (2011), Ethiopia (2011), Gabon (2012), Malawi (2010), Mozambique (2011), Rwanda (2010), Senegal (2010), Tanzania (2010), Uganda (2011) and Zimbabwe (2010). 2.1. Measures The exposure is whether a country had three consistent minimum marriage age laws of 18 and over for girls; that is, where the general minimum marriage age, the minimum marriage age with parental consent and the age of sexual consent for girls, were all set at 18 years or older. The general minimum age refers to the age at which girls can get married without parental consent. The minimum age with parental consent refers to the age at which girls require their parents’ consent to marry. The age of sexual consent refers to the age at which a girl is legally capable of agreeing to sexual intercourse, so that an adult male who engages in sex with her cannot be prosecuted for statutory rape. Countries with all three laws set at 18 years or older were defined as having consistent laws against child marriage. The outcome variables are child marriage and adolescent birth. Child marriage is a binary variable indicating whether age at first marriage or cohabitation was less than 18 years. Adolescent birth is a binary variable referring to whether age at first birth was less than 20 years. Page 6 of 29 Minimum marriage age laws and child marriage in Africa The primary question asked whether there is an association between living in a country with three consistent minimum marriage age laws and the practice of child marriage. The secondary question asked whether there is an association between living in a country with three consistent laws and adolescent birth. A common set of controls were used: • “Poor” is a series of indicator variables representing quintiles of household wealth, with the wealthiest quintile as the reference group; the wealth index, provided by the DHS, is based on ownership of specific assets (e.g., bicycle, radio and television), environmental conditions, and housing characteristics (e.g., type of water source, sanitation facilities, materials used for housing construction). • Location is a binary variable defined as 1 if the household is located in a rural area and 0 if it is located in an urban area. • Educational attainment is a binary variable defined as 1 if the highest level of school is secondary school or higher and 0 if it is primary school or less. • Religion is a categorical variable describing whether the respondent is Christian, Muslim, not religious or follows traditional or animist religions. The reference category is Christianity. Religion is a country-specific variable in DHS with each country using different coding. The variable was harmonized by recoding all unspecified observations as missing. • A binary variable for child marriage was used in the secondary research question to identify respondents whose age at first marriage or cohabitation was less than 18 years. 2.2. Statistical Analyses Page 7 of 29 Minimum marriage age laws and child marriage in Africa The study performed descriptive analyses separately for each country as well as for all countries in the sample. Descriptive statistics include univariate statistics on the independent and control variables and bivariate associations between consistent minimum marriage age laws and the outcome variables. Multivariable log binomial regression models were used to examine the association between consistent laws and child marriage on the prevalence ratio scale. Log poisson regression models were used to estimate the association between law consistency and adolescent birth, because log binomial models failed to converge.34 Independent variables were added one at a time in a series of models in order to test the strength of the coefficients; and results were presented as prevalence ratios (exponentiated regression coefficients) with 95% confidence intervals (CI) in parentheses. The highest variance inflation factor was 2.4 indicating little multicollinearity among the variables. Most DHS countries use a two-stage stratified cluster-sampling design to randomly select a fixed number of households for the survey, from primary sampling units that correspond to census enumeration areas. All eligible members in the household are asked to participate; that is, all women aged 15 to 49 years and men between 15 and 59 years.35 This sampling technique may introduce intra-cluster effects, leading potentially to underestimating coefficient standard errors. For instance, women in a particular household or region may be more likely to have married before the age of 18 years than those in other households or regions. There is no formal test to determine the appropriate clustering level for this type of survey design.36 The general convention is to cluster at the highest level when possible in order to be conservative.37 We performed the analysis with robust variance clustered alternatively at the household and the country levels. The estimated standard errors were highly sensitive to this choice of clustering, with the country-level clustering being considerably less precise. In the Page 8 of 29 Minimum marriage age laws and child marriage in Africa primary analyses shown, the more precise household clustering likely underestimates the true uncertainty. The alternative choice of clustering at the country level, with relatively small numbers of exposed and unexposed clusters, likely overestimates the uncertainty. Much of the published literature recommends the more conservative approach of overestimating uncertainty, based on the assumption that Type I errors are more costly than Type II errors in the context of statistical testing.36,37 We do not focus on statistical testing in this paper, and base interpretation more on the point estimates than on the associated intervals. While the point estimates may still be subject to endogeneity bias from unmeasured characteristics of countries with consistent laws against child marriage, the widening of the confidence intervals through the use of the robust clustering at the higher level does not correct this bias, but instead merely provides a more conservative interpretation of the estimates by representing them in the context of greater uncertainty. Faced with a choice between exaggerating the precision of our estimates and exaggerating the imprecision of our estimates, we opt for the less conservative depiction in our primary analyses because of our subjective beliefs that consistent laws are much more likely to be beneficial than harmful. Nonetheless, the estimated intervals in Tables VII and VIII should be viewed in light of this choice. All descriptive analyses were weighted using the women’s individual sample weights and STATA version 12. Multivariate analyses were not weighted, so univariate and bivariate results are representative of the population, while multivariate analyses are only generalizable to the sample of women.38 The final sample size in the 12 countries surveyed is 79 567 women aged between 15 and 26 years old. We restricted our analyses to women with non-missing information on key covariates (n=78 951). Analyses involving child marriage and adolescent birth were performed on the entire sample of women; and those involving religion were largely restricted to Page 9 of 29 Minimum marriage age laws and child marriage in Africa eleven countries (74 174 women), as Tanzania does not capture religious information in their DHS surveys. 2.3. Descriptive statistics The descriptive results are representative of 15 to 26 year old women in the population. Table II shows the general minimum marriage age, the minimum age of marriage with parental consent and the age of sexual consent for the selected group of countries in 2009. Countries with minimum marriage ages of 18 and over for all three laws are classified as having consistent marriage age laws, namely Burundi and Uganda. Rwanda and Ethiopia do not mention an exception to the general minimum marriage age with parental consent and have an age of sexual consent of 18 years. They are classified as having consistent marriage age laws for the purposes of this research. Countries where one or more of these three laws are set at less than 18 years are classified as having inconsistent laws namely: Burkina Faso, Cameroon, Gabon, Malawi, Mozambique, Senegal, Tanzania and Zimbabwe. Not applicable refers to legislations that do not specify minimum ages, while missing data indicates unclear or contradictory data for the country concerned. [Insert Table II here] The number of ever married women is 41 103, 23 760 (57%) of who were married before the age of 18. Table III shows that the highest rate of child marriage is in Mozambique where almost half of the women surveyed were married before the age of 18 (42.3%), followed closely by Burkina Faso (41.5%) and Malawi (38%). Rwanda has the lowest prevalence of the countries surveyed with approximately one in twenty girls in the country marrying before the age of 18 (6%). Page 10 of 29 Minimum marriage age laws and child marriage in Africa There are generally high levels of adolescents giving birth in the countries surveyed. Mozambique (48%), Malawi (46%) and Burkina Faso (41%) have the highest rates of respondents giving birth to their first child before the age of 20 years. Gabon has the biggest margin between child marriage and adolescent birth rates; twice as many women there give birth before 20 (37%) as are married as children (18%). [Insert Table III here] Child marriage rates were slightly higher in countries with inconsistent laws against child marriage (Table IV). On average, one quarter (26%) of girls who married as children in these countries married before the age of 15 years, compared to 23% girls in consistent countries. Ethiopia (40%), Senegal (39%) and Cameroon (36%) have the highest rates of girls marrying before 15 in the countries surveyed. It is interesting to note that the highest proportion of girl children marry at the age of parental consent in four countries, namely Burkina Faso (17 years), Cameroon (15 years), Mozambique (16 years) and Zimbabwe (16 years). [Insert table IV here] 3. Results Table V presents child marriage rates and adolescent birth rates for all women by demographics and law consistency, showing mean proportions for all countries, with ranges in parenthesis. There are high levels of exposure to factors associated with child marriage among the sample of women. The majority of women live in rural areas (64%) and have low levels of educational attainment, with only 4% of women completing thirteen or more years of schooling. There are however wide variations across countries, for example two thirds of women in Burkina Faso (64%) did not go to school compared to less than 1% of women in Zimbabwe (0.5%). Page 11 of 29 Minimum marriage age laws and child marriage in Africa On average, women living in countries with inconsistent laws against child marriage have higher rates of child marriage and higher rates of adolescent childbearing across almost all demographic characteristics. However, the gap (potential protective effect) is largest for women in the poorest wealth quintile, those living in rural areas and those with the lowest educational attainment. For example, the child marriage rate for women living in consistent countries who fall into the poorest wealth quintile is 17% lower than for the poorest women in countries with inconsistent laws. The child marriage rate is only 2% lower for women in consistent countries who fall into the wealthiest quintile. With respect to religion, Christianity appears to be associated with a lower rate of child marriage in both sets of countries. Tradition and Islam are often used in defense of the practice of child marriage on the African continent10 so the proportion of religious groups in each country may influence both the pervasiveness and intractability of the practice. [Insert Table V here] Individual country-level data in Table VI compares means for child and adult marriages. Overall, child marriages occur on average four years before adult ones, sexual debut occurs approximately two years earlier and the mean age at first birth occurs three years earlier. An analysis of adolescent birth reveals that the vast majority of women who marry as children (83%) give birth to their first child before the age of twenty. This rate is more than five times that of women who marry as adults (15%). [Insert Table VI here] A series of prevalence ratio models was used to estimate the adjusted association between law consistency and child marriage. The results are presented as adjusted prevalence ratios with confidence intervals in parentheses (Table VII). There are significant positive associations Page 12 of 29 Minimum marriage age laws and child marriage in Africa between poverty and child marriage as well as between location and child marriage. For instance, with controls, women in the poorest wealth quintile are 53% more likely to enter into a child marriage than those in the richest wealth quintile (PR = 1.53, 95% CI = 1.47 – 1.61). There is also a significant negative association between schooling and child marriage; proceeding to secondary school was associated with a 59% lower risk of entering into a child marriage (PR = 0.41, 95% CI = 0.39 – 0.43). The sample of women in countries with consistent minimum marriage age laws of 18 years or over for girls are 40% less likely to marry as children (PR = 0.60, 95% CI = 0.55 – 0.66) when clustering at the household level (Table VII). [Insert Table VII here] A series of prevalence ratio regression models was also performed to estimate the association between law consistency and adolescent childbirth. The results are presented as adjusted prevalence ratios with confidence intervals in parentheses (Table VIII). There are significant associations between law consistency and adolescent birth as well as between child marriage and adolescent birth. For example, with controls, women who live in countries with consistent laws against child marriage are 25% less likely to have a child before the age of 20 years (PR = 0.75, 95% CI = 0.73 – 0.78), while those who married as children are almost five times as likely to give birth as adolescents (PR = 4.82, 95% CI = 4.58 – 5.07). [Insert Table VIII here] 5. Discussion This paper finds some suggestion of a negative association between law consistency and child marriage, and between law consistency and adolescent birth. Holding poverty, educational attainment, religion and rural-urban location constant, women in countries with consistent Page 13 of 29 Minimum marriage age laws and child marriage in Africa minimum marriage age laws of 18 years or over for girls were only two-thirds as likely to marry as children and three quarters as likely to give birth as an adolescent. In other words, the prevalence of child marriage and adolescent childbearing may be lower in households located in countries where the general minimum marriage age, the minimum marriage with parental consent, and the age of sexual consent are all set at 18 years or older for girls, namely Burundi, Ethiopia, Rwanda and Uganda. Girls may thus be more likely to marry before the age of 18 years and give birth before the age of 20 years in countries where these laws are inconsistent and where there is effectively no legal proscription against child marriage, namely: Burkina Faso, Cameroon, Gabon, Malawi, Mozambique, Senegal, Tanzania and Zimbabwe. Our results are consistent with the hypothesis that setting consistent minimum marriage age laws of 18 years, may protect against the exploitation of girl children. Girls who marry before the age of 18 are five times as likely to give birth as adolescents. This result is consistent with a number of other studies indicating an association between child marriage and early child bearing.12,13 There is sizeable literature showing that adolescent childbearing is associated with more severe obstetric outcomes relative to adult childbearing, such as fistula, miscarriage, preterm births, lower birth weights, stunting and higher infant and maternal mortality rates.15-20,22,24-26 Although proportionally fewer adolescents are giving birth in countries with consistent laws against child marriage, the percentages are high in both sets of countries. Three quarters of women who have ever given birth in countries with inconsistent laws (76%) and two thirds of the women who have ever given birth in countries with consistent laws (62%), gave birth as adolescents and faced elevated risks compared to women giving birth at 20 years or older. Page 14 of 29 Minimum marriage age laws and child marriage in Africa This study controlled for a number of factors that have previously been associated with both child marriage and adolescent childbearing such as rural/urban residence, religion, poverty and education. DHS data captures total achieved education rather than educational level at the time of marriage. The former variable may introduce potential reverse causality due to the bidirectional relationship between child marriage and education (child marriage limits education, but girls who are not in school may also be more available for marriage). We used a binary educational attainment variable to account for this, as well as to minimize differences in education systems across countries. That is, we classify the highest level of educational attainment into either none/primary or secondary/higher. Relatively low rates of girls marrying before the age of 14 (Table IV) suggests that primary school completion is likely to precede child marriage in most, but not all cases. A number of other mechanisms may influence the relationship between child marriage and adolescent childbearing. Lower levels of knowledge about contraceptive use, the often considerable pressure to prove fertility soon after marriage and higher mean spousal age differences in child marriages combined with lower levels of education often lead girls to become psychologically and economically dependent on husbands and in-laws. This may compromise a girl’s ability to control or negotiate over her own reproductive health.2,5 Region is a potential effect modifier that was not controlled for in this descriptive paper. Country level statistics hide the often considerable regional variation in the practice of early marriage by country, particularly in Ethiopia where the majority of child marriages occur in the Amhara region in the north of the country.39 The statistical significance of the results was sensitive to how we handled clustering. Angeles et al.37 argue that it is possible to obtain both reliable point estimates and coefficient standard errors Page 15 of 29 Minimum marriage age laws and child marriage in Africa in models with two or more levels by clustering at the highest level. This study clusters at both the country and household level and finds that the standard errors are substantially larger in the former (Tables not shown). Individual level variables such as child marriage and religion are particularly sensitive when clustering at the highest level. There may therefore be a clustering and weighting effect in these models, as the many different types of households in each country respond differently to their respective legal and religious environments. Several unobserved factors may influence the effectiveness of laws in the study. Legal frameworks and policy environments governing minimum marriage ages laws differ greatly across the continent. Some countries criminalize child marriages; some ban or invalidate marriage below the legally prescribed minimum age; and others merely prescribe a minimum age of marriage without expressly criminalizing or banning child marriage. Punishment also varies from fines to prison terms or a combination of both. Moreover, laws must be communicated to and adopted by communities, particularly in remote rural areas where child marriage is more prevalent. They must also be enforced by local officials so corruption, limited monitoring and enforcement capabilities and resistance from the community or even local officials may also have an influence on law effectiveness. To the best of our knowledge, there are no studies examining whether girls, parents and communities are aware of minimum marriage laws, or the extent to which laws are enforced. The study also highlights some of the challenges to curbing the practice of child marriage on a continent where pluralistic legal systems are the norm. For instance, the minimum age of marriage with parental consent is lower than the age of sexual consent in Gabon and Tanzania. This is problematic because a valid marriage needs to be consummated. Many such legal discrepancies result from the fact that marriage laws in sub-Saharan Africa are governed by Page 16 of 29 Minimum marriage age laws and child marriage in Africa statutory as well as customary or religious laws that may be contradictory and contravene international or regional human rights laws. Additionally, many sub-Saharan African countries have legal exceptions allowing for underage marriage. Almost all the countries surveyed, including Uganda with consistent 18+ minimum marriage age laws allow marriage at a younger age with court approval or ‘under exceptional circumstances’. It is difficult to determine how often these exceptions are used to marry children off given the general paucity of marriage data on the continent. Additionally, age at first marriage and age at first birth are self-reported and consequently may be prone to bias. For example, four countries display small spikes in the proportion of girl children married at the minimum marriage age with parental consent, namely Burkina Faso (17), Cameroon (15), Mozambique (16) and Zimbabwe (16). It is difficult to interpret this age heaping as marriage ages may have been misreported with a bias towards the legal age, or parents may be waiting until the age of parental consent to marry children off. There are thus limitations to a study involving marriage in sub-Saharan Africa, and the aim of this paper is consequently narrow, that is to examine associations between law consistency, child marriage rates and adolescent childbirth. The paper is designed as an exploratory cross-sectional study using data from 2010 to 2012 and does not account for the year the minimum marriage age law changed. Results will therefore not imply causality at this stage. The findings from this descriptive analysis need to be tested with more rigorous approaches that control for longitudinal variation, changing social trends and country-level confounding. This paper nonetheless provides two important insights for policy makers. Firstly, the negative association between consistent 18+ minimum marriage laws and child marriage rates suggests that having consistent laws may have an impact on the practice of child marriage. And secondly, the negative association between Page 17 of 29 Minimum marriage age laws and child marriage in Africa law consistency and adolescent birth suggests that having consistent laws against marriage may also have an impact on adolescent birth. It is also important to note that consistent laws against child marriage may be associated with lower child marriage rates among those who, according to the literature, are more vulnerable to child marriage (poor, uneducated women living in rural areas). Women in countries with consistent 18+ marriage age laws are less likely to marry before the age of 18 across all demographic characteristics, but the gap (potential protective effect) is largest for women in the poorest wealth quintiles, those living in rural areas and those with the lowest educational attainment. For example, the child marriage rate for rural women living in countries with consistent laws is 17% lower than for rural women in countries with inconsistent laws, while the child marriage rate is only 7% lower for women in consistent countries who live in urban areas. The purpose of this descriptive study was to assess the association between child marriage and minimum marriage age laws in preparation for an analytical study that will address the causality limitations inherent in cross-sectional studies. Repeated cross-sectional data and causal policy analysis methods can be used to examine the impact of minimum marriage age laws on the practice of child marriage and on a range of reproductive health outcomes. Higher risks of child marriage and adolescent birth for 15 to 26 year old women living in countries with inconsistent laws against marriage, suggest that raising minimum marriage age laws and harmonizing various laws so that they are all consistently set at 18 years or over, is a crucial step to curbing the harmful practice of child marriage and possibly improving maternal and child health outcomes. Page 18 of 29 Minimum marriage age laws and child marriage in Africa References 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. 7. 8. 9. 10. 11. 12. 13. 14. 15. 16. 17. 18. United Nations Children's Fund (UNICEF), Early Marriage: A Harmful Traditional Practice, New York: UNICEF, 2005. United Nations Children's Fund (UNICEF), Early marriage: child spouses, Innocenti Digest No. 7, Florence: UNICEF, 2001. Convention on the Elimination of all Forms of Discrimination against Women (CEDAW), 1979, < http://www.un.org/womenwatch/daw/cedaw/cedaw.htm >, accessed Feb. 2, 2015. Convention on the Rights of the Child (CRC), 1989, <http://www.ohchr.org/en/professionalinterest/pages/crc.aspx>, accessed Feb. 2, 2015. International Planned Parenthood Federation (IPPF), Ending Child Marriage: A guide for Global Policy Action, London: IPPF, 2006. Nour N, Health consequences of child marriage in Africa, Emerging Infectious Diseases, 2006, 12(11):1644-1649. United Nations Treaty Collection, Chapter IV Human Rights: The Convention on the Rights of the Child, < https://treaties.un.org/Pages/ViewDetails.aspx?mtdsg_no=IV11&chapter=4&lang=en>, accessed Feb. 2, 2015. United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF), The African Charter on the Rights and Welfare of the Child, UNICEF Eastern and Southern Africa: For Children and Youth, <http://www.unicef.org/esaro/children_youth_5930.html>, accessed Feb. 5, 2015. African Committee of Experts on the Rights and Welfare of the Child (ACERWC), The African Charter on the Rights and Welfare of the Child (ACRWC), <http://acerwc.org/the-african-charter-on-the-rights-and-welfare-of-the-child-acrwc/>, accessed Jan. 27, 2015. Walker J, Early marriage in Africa - trends, harmful effects and interventions, African Journal of Reproductive Health, 2012, 16(2):231-240. Jensen R and Thornton R, Early female marriage in the developing world, Gender and Development, 2003, 11(2):9-19. Mensch B, Bruce J and Greene M, The Uncharted Passage: Girls' Adolescence in the Developing World, New York: Population Council, 1998. Williamson N and Blum R, Motherhood in Childhood: Facing the Challenge of Adolescent Pregnancy, New York: United Nations Population Fund State of the World Population Report, 2013. Westoff C, Trends in Marriage and Early Childbearing in Developing Countries, Calverton: ORC Macro, 2003. Kumbi S and Isehak A, Obstetric outcome of teenage pregnancy in Northwestern Ethiopia, East African Medical Journal, 1999, 76(3):138-140. Adedoyin M and Adetoro O, Pregnancy and its outcome among teenage mothers in Ilorin, Nigeria, East African Medical Journal, 1989, 66(7):448-452. Fraser A, Brockert J and Ward R, Association of young maternal age with adverse reproductive outcomes, New England Journal of Medicine, 1995, 332(17):1113-1118. Santhya K, Ram U, Acharya R, Jejeebhoy S, Ram F and Singh A, Associations between early marriage and young women's marital and reproductive health outcomes: evidence from India, International Perspectives on Sexual and Reproductive Health, 2010, 36(3):132-139. Page 19 of 29 Minimum marriage age laws and child marriage in Africa 19. 20. 21. 22. 23. 24. 25. 26. 27. 28. 29. 30. 31. 32. 33. 34. 35. United Nations Children's Fund (UNICEF), We the Children: End-Decade Review of the Follow-up to the World Summit for Children, New York: UNICEF, 2000. Adhikari R, Early marriage and childbearing: risks and consequences, in: Bott S, Jejeebhoy S, Shah I and Puri C, eds., Towards Adulthood: Exploring the Sexual and Reproductive Health of Adolescents in South Asia, Geneva: World Health Organization; 2003, pp. 62-66. Raj A, Saggurti N, Winter M, Labonte A, Decker M, Balaiah D and Silverman J, The effect of maternal child marriage on morbidity and mortality of children under 5 in India: cross sectional study of a nationally representative sample. British Medical Journal, 2010, 340 (b4258):1-9. Nepal Ministry of Health, Family Health Survey 1996, Kathmandu: Department of Health Services, Government of Nepal, 1996. Nour N, Child marriage: a silent health and human rights issue, Reviews in Obstetrics and Gynecology, 2009, 2(1):51-56. Oyefara J, Socio-economic consequences of adolescent childbearing in Osun State, Nigeria, KASBIT Business Journal, 2009, 2(1&2):1-18. Raj A, Saggurti N, Balaiah D and Silverman J, Prevalence of child marriage and its effect on fertility and fertility-control outcomes of young women in India: a cross-sectional, observational study, The Lancet, 2009, 373(9678):1883-1889. Godha D, Hotchkiss D and Gage A, Association between child marriage and reproductive health outcomes and service utilization: a multi-country study from South Asia, Journal of Adolescent Health, 2013, 52(5):552-558. Huntington D, Lettenmaier C and Obeng-Quaidoo I, User's perspective of counseling training in Ghana: the "Mystery Client" trial, Studies in Family Planning, 1990, 21(3):171-177. Bruce J, Child marriage in the context of the HIV epidemic, Transitions to Adulthood, Brief No.11, New York: Population Council, 2007. Clark S, Bruce J and Dude A, Protecting young women from HIV/AIDS: the case against child and adolescent marriage, International Family Planning Perspectives, 2006, 32(2):79-88. Speizer I and Pearson E, Association between early marriage and intimate partner violence in India: a focus on youth from Bihar and Rajasthan, Journal of Interpersonal violence, 2011, 26(10):1963-1981. Erulkar A, Early marriage, marital relations and intimate partner violence in Ethiopia, International Perspectives on Sexual and Reproductive Health, 2013, 39(1):6-13. United Nations Children's Fund (UNICEF), State of the World's Children 2013: Children with Disabilities, New York: UNICEF, 2013. Corsi D, Neuman M, Finlay J and Subramanian S, Demographic and health surveys: a profile, International Journal of Epidemiology, 2012, 41(6):1602-1613. Zou G, A modified poisson regression approach to prospective studies with binary data, American Journal of Epidemiology, 2004, 159(7):702-706. Vaessen M, Thiam M and Lê T, Chapter XXII: the demographic and health surveys, in: United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs (UNDESA), Household Sample Surveys in Developing and Transition countries, New York: UNDESA Statistics Division, 2005, pp. 495-522. Page 20 of 29 Minimum marriage age laws and child marriage in Africa 36. 37. 38. 39. Cameron A and Miller D, Robust inference with clustered data, in: Ullah A and Giles D, eds., Handbook of Empirical Economics and Finance, Boca Raton: CRC Press, 2010, pp. 1-28. Angeles G, Guilkey D and Mroz T, The impact of community-level variables on individual-level outcomes: theoretical results and applications, Sociological Methods & Research, 2005, 34(1):76-121. Rutstein S and Rojas G, Guide to DHS Statistics, Calverton: ORC Macro, 2006. Erulkar A and Muthengi E, Evaluation of Berhane Hewan: a program to delay child marriage in rural Ethiopia, International Perspectives on Sexual and Reproductive Health, 2009, 35(1):6-14. Acknowledgements The authors gratefully acknowledge and would like to thank Dr. Chris Desmond, José Mendoza Rodriguez, Ilona Vincent and Efe Atabay for their support and assistance in preparing the manuscript. Page 21 of 29 Minimum marriage age laws and child marriage in Africa Table I: Countries with the highest child marriage rates in the world % of 20 to 24 year olds who were married or in a union before 18 1 Niger 2 Chad 3 Central African Republic 4 Bangladesh 5 Guinea 6 Mozambique 7 Mali 8 Burkina Faso 9 South Sudan 10 Malawi 11 Madagascar 12 Eritrea 13 India 14 Somalia 15 Sierra Leone 16 Zambia 17 Dominican Republic 18 Ethiopia 19 Nepal 20 Nicaragua 75 68 68 66 63 56 55 52 52 50 48 47 47 45 44 42 41 41 41 41 Source: UNICEF State of the World's Children, 2013. Data from the most recent UNICEF Multiple Indicator Cluster Surveys (MICS) and Demographic and Health Surveys (DHS) during the period 2002-2011. Page 22 of 29 Minimum marriage age laws and child marriage in Africa Table II: Minimum marriage ages for men and women by country Consistent 18+ laws National minimum age Parental consent Male Female Male Female Burundi 21 21 n/a 18 Uganda 21 21 18 18 Ethiopia 18 18 n/a n/a Rwanda 21 21 n/a n/a Inconsistent laws against child marriage National minimum age Parental consent Male Female Male Female Burkina Faso 20 20 n/a 17 Cameroon missing data missing data 18 15 Gabon 21 21 18 15 Malawi 18 18 15 15 Mozambique 18 18 16 16 Senegal 18 18 n/a 16 Tanzania 18 18 n/a 15 Zimbabwe 18 18 n/a 16 Age of sexual consent Male Female 18 18 18 18 18 18 18 18 Age of sexual consent Male Female 13 13 16 16 18 18 13 13 n/a n/a 16 16 18 18 16 16 Source: 2009 MACHEquity child marriage database: Age of consent source: FOSIGRID. Missing data – the marriage age is unclear based on the legislations due to contradictions. N/A – the legislations does not mention a minimum marriage age. Page 23 of 29 Minimum marriage age laws and child marriage in Africa Table III: Child marriage rates and adolescent births by country Country Survey Sample Sample % No. married year Size before 18 Mozambique 2011 6 515 8.1 2 538 B. Faso 2010 7 889 9.9 3 144 Malawi 2010 11 226 14.3 4 297 Ethiopia 2011 8 534 10.8 2 939 Cameroon 2011 7 922 10.0 2 570 Uganda 2011 4 375 5.4 1 286 Senegal 2010 8 127 10.0 2 779 Tanzania 2010 4 778 6.0 1 191 Zimbabwe 2010 4 529 5.7 1 075 Gabon 2012 3 960 5.1 882 Burundi 2010 4 971 6.2 671 Rwanda 2010 6 741 8.4 388 Total 79 567 100% 23 760 Child marriage % 42.3 41.5 37.6 33.6 32.2 30.4 29.3 27.9 25.4 17.6 14.2 6.0 29.8 % first birth before 20 48.1 41.1 46.2 28.4 37.1 39.3 28.7 38.6 34.0 36.7 20.5 12.6 34.8% Source: DHS 2010-2012. All rates are weighted. All percentages are weighted and performed on the sample of women aged 15 to 26 years old (N= 79 567). Parental consent refers to minimum marriage age with parental consent Page 24 of 29 Parental consent 16 17 15 n/a 15 18 16 15 16 15 18 n/a 16.7 Minimum marriage age laws and child marriage in Africa Table IV: Proportion of child marriages by age and country Proportion of child marriages by age of marriage Countries with consistent laws against child marriage 13 or 14 years 15 years 16 years 17 years younger Burundi 5.1 9.1 16.3 27.6 41.9 Uganda 13.6 10.6 21.2 26.0 28.6 Ethiopia 25.8 14.1 23.4 18.7 18.0 Rwanda 4.6 7.1 12.7 30.7 45.0 Mean (%) 12.3 10.2 18.4 25.8 33.4 Countries with inconsistent laws against child marriage Burkina Faso 7.2 13.5 22.1 26.6 30.6* Cameroon 18.9 17.5 22.6* 19.9 21.1 Gabon 13.1 15.8 18.5 24.6 28.0 Malawi 9.7 11.6 20.6 28.2 29.9 Mozambique 14.8 15.3 22.3 26.3* 21.2 Senegal 23.1 15.9 22.2 18.7 20.2 Tanzania 6.2 11.2 21.2 31.3 30.2 Zimbabwe 4.7 9.0 19.6 29.3* 37.4 Mean (%) 12.2 13.7 21.1 25.6 27.3 Median age 18.8 17.5 16.7 20.3 18.3 Parental consent 18 18 n/a n/a 17.1 17.0 18.3 17.3 16.9 17.3 17.7 18.3 17.5 17 15 15 15 16 16 15 16 Source: DHS Surveys 2010-2012. All proportions are weighted percentages of all respondents who married before the age of 18 (N= 23 760) Weighted median age of marriage for all women in each country Parental consent refers to minimum marriage age with parental consent. * Indicates the largest proportion of girl children marrying at the minimum marriage age with parental consent. Page 25 of 29 Minimum marriage age laws and child marriage in Africa Table V: Child marriage and adolescent birth rates by demographics and law consistency. Child marriage rates Adolescent birth rates Sample Consistent laws Inconsistent Consistent laws Inconsistent Distribution laws laws Mean Mean Mean Mean Mean (Min, Max) (Min, Max) (Min, Max) (Min, Max) (Min, Max) Poorest 16.2 29.4 46.6 32.7 52.4 (13.7, 19.4) (9.6, 45.5) (26.1, 58.4) (17.9, 50.5) (48.4, 57.1) Poor 18.2 25.7 41.6 30.0 47.5 (16.6, 20.2) (5.4, 41.5) (23.5, 55.2) (13.2, 50.0) (38.3, 54.8) Middle 19.5 23.3 36.3 27.3 43.3 (17.4, 22.6) (6.2, 39.3) (20.1, 51.1) (11.8, 43.6) (24.9, 53.7) Rich 20.8 18.9 29.2 22.3 37.1 (18.9, 24.4) (5.5, 25.0) (5.5, 47.2) (11.1, 34.1) (20.8, 53.8) Richest 25.4 13.0 14.8 18.1 22.7 (21.6, 29.3) (3.9, 17.5) (7.8, 20.9) (10.2, 27.1) (15.6, 35.0) Rural Urban Christian Muslim Traditional No religion None Primary (1-6 years) Secondary (7 – 12 years) Post-secondary (13 + years) Total (79 567) 63.9 (10.3, 88.5) 36.1 (11.5, 89.7) 23.4 (6.3, 83.9) 13.3 (4.4, 18.7) 40.1 (27.8, 50.9) 20.7 (15.6, 30.1) 27.1 (12.6, 42.0) 19.2 (12.9, 29.9) 46.9 (38.8, 54.6) 29.7 (18.4, 42.2) 73.1 (4.2, 98.1) 23.8 (0.3, 95.4) 0.9 (0, 5.6) 2.2 (0, 9.1) 20.3 (5.8, 31.8) 27.6 (10.9, 38.0) n/a 24.0 (12.3, 38.1) 37.5 (24.0, 47.3) n/a 28.0 (24.8, 31.2) 25.8 (10.6, 40.8) 40.9 (20.5, 58.2) 51.5 (10.1, 80.8) 42.4 (31.1, 59.0) 42.5 (39.1, 45.8) 34.6 (18.3, 47.4) 45.8 (29.1, 56.1) 61.5 (54.4, 72.0) 48.3 (36.4, 66.7) 21.2 (0.5, 63.8) 34.7 (8.2, 71.2) 40.3 (13.7, 85.7) 3.8 (0.7, 10.9) 39.0 (18.8, 58.4) 20.5 (5.5, 38.5) 10.5 (2.2, 22.7) 2.6 (0 , 7.1) 21.6% 52.3 (35.1, 53.9) 38.2 (21.4, 58.1) 18.4 (6.6, 25.9) 4.3 (0, 12.4) 33.4% 43.4 (28.4, 62.3) 23.9 (12.6, 44.6) 15.0 (5.9, 35.8) 5.2 (2.6, 6.9) 24.4% 58.2 (42.9, 67.7) 44.9 (22.8, 60.3) 27.5 (7.8, 38.0) 6.7 (0.3, 24.0) 39.5% Source: DHS 2010-2012 Child marriage rate, mean proportion of all women aged 15 to 26 years, whose age at first marriage was less than 18. Adolescent birth rate, mean proportion of all women aged 15 to 26 years whose age at first birth was less than 20 years (N= 79 567). Page 26 of 29 Minimum marriage age laws and child marriage in Africa Table VI: Country level data by law consistency Countries with consistent Laws Mean age at first Mean age at first Mean age of marriage birth sexual debut Child Adult Child Adult Child Adult Burundi 16.4 20.1 17.1 20.4 15.9 17.6 Uganda 15.8 20.0 16.5 19.3 15.1 16.7 Ethiopia 15.0 19.9 17.0 20.5 14.7 18.1 Rwanda 16.5 21.0 17.6 20.8 16.0 17.6 Mean 15.9 20.3 17.1 20.3 15.4 17.5 Countries with inconsistent laws Mean age at first Mean age at first Mean age of marriage birth sexual debut Child Adult Child Adult Child Adult Burkina Faso 16.0 19.6 17.1 20.0 15.8 17.6 Cameroon 15.4 20.4 16.5 19.2 15.3 16.7 Gabon 15.8 20.7 16.7 18.1 15.2 16.3 Malawi 16.0 19.6 16.8 19.4 15.2 16.9 Mozambique 15.6 20.1 16.4 18.9 14.8 16.1 Senegal 15.2 20.5 16.4 20.2 15.3 18.2 Tanzania 16.1 20.1 17.0 19.2 15.1 16.6 Zimbabwe 16.3 20.3 17.0 19.9 16.1 18.8 Mean 15.8 20.2 16.7 19.4 15.4 17.2 % giving birth before 15 Child Adult 4.9 0.1 13.4 0.8 7.5 0.0 3.5 0.1 7.3 0.3 % giving birth before 20 Child Adult 87.0 9.6 88.3 17.9 72.3 6.2 90.8 7.7 84.6 10.4 % giving birth before 15 Child Adult 4.3 0.1 13.6 1.2 12.6 2.6 7.7 0.5 11.4 1.9 14.9 0.5 5.7 1.0 3.7 0.2 9.2 1.0 % giving birth before 20 Child Adult 81.0 12.8 78.5 17.5 74.4 28.6 88.6 20.6 78.3 26.0 75.9 9.2 86.1 20.3 84.6 16.7 80.9 18.9 Source: DHS 2010-2012 Weighted means of women 15 to 26 years old in each country (N=79 567). Adolescent rates are weighted proportions of women in each country. The total number who married as children in all countries is 23 759 and total number who married as adults is 17 343. Page 27 of 29 Minimum marriage age laws and child marriage in Africa Table VII: Prevalence ratio models for associations between law consistency and child marriage, household level clustering. Child marriage Consistent 18+ laws Richest quintile (ref) Richer Middle Poorer Poorest Model 1 (N = 79 567) Model 2 (N = 79 567) Model 3 ((N = 79 547) Model 4 (N = 79 547) Model 5 (N = 74 173) 0.64*** (0.58 to 0.70) 0.66*** (0.60 to 0.73) 0.58*** (0.53 to 0.64) 0.58*** (0.52 to 0.63) 0.60*** (0.55 to 0.66) 1.69*** (1.61 to 1.78) 2.04*** (1.95 to 2.14) 2.28*** (2.18 to 2.38) 2.61*** (2.49 to 2.73) 1.40*** (1.33 to 1.46) 1.51*** (1.44 to 1.58) 1.63*** (1.56 to 1.70) 1.74*** (1.66 to 1.82) 1.33*** (1.26 to 1.39) 1.41*** (1.34 to 1.48) 1.50*** (1.42 to 1.57) 1.60*** (1.53 to 1.68) 1.29*** (1.23 to 1.36) 1.35*** (1.28 to 1.42) 1.45*** (1.38 to 1.52) 1.53*** (1.47 to 1.61) 0.37*** (0.35 to 0.38) 0.38*** (0.36 to 0.39) 0.41*** (0.39 to 0.43) 1.14*** (1.10 to 1.19) 1.19*** (1.14 to 1.24) Primary school or less (ref) Secondary school or higher Urban location (ref) Rural location Christian (ref) Muslim 1.25*** (1.20 to 1.30) 1.31*** (1.24 to 1.39) 1.23*** (1.15 to 1.31) Traditional No religion Source: DHS 2010-2012 Household level clustering. 95% confidence level in parentheses. Indicates significance at: *p<0.05. **p<0.01. *** p<0·001. +p<0·10. N=79 567 women aged 15 to 26 years old. Page 28 of 29 Minimum marriage age laws and child marriage in Africa Table VIII: Prevalence ratio models for associations between law consistency and adolescent birth, household level clustering. Adolescent birth Consistent 18+ laws Child marriage Richest quintile (ref) Richer Middle Poorer Poorest Model 1 (N = 79 567) Model 2 (N = 79 567) Model 3 (N = 79 567) Model 4 (N = 79 547) Model 5 (N = 74 173) 0.77*** (0.74 to 0.80) 5.09*** (4.86 to 5.33) 0.78*** (0.75 to 0.81) 4.90*** (4.67. to 5.14) 0.76*** (0.73 to 0.79) 4.74*** (4.53 to 4.97) 0.77*** (0.74 to 0.80) 4.75*** (4.53 to 4.98) 0.75*** (0.73 to 0.78) 4.82*** (4.58 to 5.07) 1.15*** (1.11 to 1.18) 1.20*** (1.16 to 1.24) 1.23*** (1.19 to 1.28) 1.27*** (1.23 to 1.32) 1.12*** (1.08 to 1.16) 1.16*** (1.11 to 1.20) 1.18*** (1.14 to 1.23) 1.21*** (1.16 to 1.27) 1.14*** (1.10 to 1.18) 1.19*** (1.14 to 1.24) 1.22*** (1.16 to 1.28) 1.26*** (1.19 to 1.32) 1.14*** (1.10 to 1.18) 1.19*** (1.14 to 1.24) 1.22*** (1.16 to 1.27) 1.26*** (1.20 to 1.33) 0.87*** (0.84 to 0.89) 0.86*** (0.83 to 0.88) 0.86*** (0.83 to 0.89) 0.95** (0.92 to 0.98) 0.95** (0.92 to 0.98) Primary school or less (ref) Secondary school or higher Urban location (ref) Rural location Christian (ref) Muslim 0.87*** (0.84 to 0.89) 0.94* (0.89 to 0.99) 1.10*** (1.05 to 1.15) Traditional No religion Source: DHS 2010-2012 Household level clustering. 95% confidence level in parentheses. Indicates significance at: *p<0.05. **p<0.01. *** p<0·001. +p<0·10. N=79 567 women aged 15 to 26 years old. Page 29 of 29