small town newspapers - Center for Peripheral Studies

advertisement

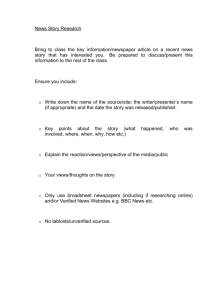

Small Town Newspapers: Ethnography and Folkloristics of Everyday Written Narrative (Rejected by Journal of American Folklore) Lee Drummond Center for Peripheral Studies www.peripheralstudies.org leedrummond@msn.com Small Town Newspapers: Ethnography and Folkloristics of Everyday Written Narrative Abstract Although much attention has been given to the ethnography of speech, and even more attention to the narrative analysis of traditional genres such as folk tales and myth, relatively little anthropological research has been done on common or everyday written narrative and its place in community life. Yet as formerly traditional peoples become modernized and as anthropologists become increasingly interested in their own, literate societies, the written productions of “new natives” will prove to be an important source of ethnographic material. This essay seeks to address that issue by examining the relationships among several communities of western Montana and the weekly newspapers published in those communities. The central problem of the essay is the nature of the relation between a community, considered as the object of ethnographic investigation, and an indigenous written production about that community, considered as folkloric material. The essay attempts to demonstrate that that relation is neither arbitrary nor a matter of simple reflection, but an integral function of the community considered as a system f significations. Distributional and associative features of newspaper content are examined, and the latter are related to a complex of ethnographically specified cultural themes that appear to operate in the several small towns. This study was conducted and the results analyzed by a collaboration of two anthropology graduate students at the University of Montana, William Dakin and Susan Boyd, and myself. Their contributions were invaluable; the project could not have been done without them. ……………………………………………… 2 I In a collection of seminal essays, William O. Hendricks (1973) argues persuasively for an approach to narrative analysis that integrates techniques developed in linguistics and folkloristics. The task of accommodating aspects of the two disciplines involves him in a consideration of the sharp distinction folklorists have traditionally drawn between oral and written narrative. He concludes that an adequate theory of narrative structure would relegate differences between oral and written forms to a contingent status, regarding them simply as variations in mode of transmission rather than basic structure. Rather than identify folklore exclusively with oral narrative, he makes the intriguing suggestion that writing, once acquired, takes on folkloric functions in a literate society. A seemingly reasonable hypothesis is that as literacy increases, folklore increasingly becomes something transmitted by the graphic medium. . . one can point out that in non-literate societies everything — including folklore — is orally transmitted. If the society acquires an orthography, functional uses of language may be differentiated as to mode of transmission, oral or written. The fact that writing may now be used for certain functions should not suggest that these functions have disappeared. (page 84) Hendricks explores parallels between oral and written narrative structure with examples drawn from English literature, giving extensive, and brilliant, analyses of works by William Faulkner, Ray Bradbury, and Ambrose Bierce. Despite his focus on polished literary works, he notes3 that discourse analysis in its present formative stage might first examine the everyday accounts of daily experience given by more-or-less ordinary people before trying to decode the structure of traditional tales told by verbal artists. The suggestion carries implications that furnish the subject of this essay. In proposing that folktales and literary works may have more in common structurally than does either genre with spontaneous verbal activity, Hendricks calls into question the homology that is sometimes supposed to hold between the two oppositions, oral/written and non-specialist/specialist. If the status of narrator (language specialist vs. non-specialist) and the mode of transmission (written vs. oral) are not determinatively related, then four narrative types based on these binary pairs can be identified (see Figure 1). 3 Figure 1. Four Permutations of Narrative Type Oral Written Specialist traditional folklore, professional speakers, disc jockeys, sportscasters, talk show hosts, some news reporters, teachers, clergy, politicians Non-Specialist everyday accounts of personal experience (ordinary conversations or what in the media have become known as “man in the street” interviews) literature, national magazines, large-circulation newspapers, technical reports, monographs, business letters personal letters (individual focus), school essays, small town newspapers (group focus) At present, three of the four narrative types identified in the paradigm are subjects of lively scholarly discussion. The “specialist” oral genre of traditional folklore (which may now be extended to include productions of modern verbal performers such as television news reporters and talk show moderators) are under the competent scrutiny of the folklorist and, for more recent productions, the cultural studies analyst. The “specialist” written genre of literature, (including national magazines and other highly polished professional works) are intensively studied by literary critics of every persuasion, including a large coterie of the cultural studies people. The “non-specialist” oral genre of everyday speech and individuals’ accounts of personal experiences (what the media calls “man in the street” accounts) is the subject of exciting research by workers in the rapidly expanding field of “the ethnography of speaking.”4 The fourth type, however, which consists of the written productions of nonspecialists, has been less well examined. In a brief programmatic article on “the ethnography of writing,” Basso (1974: 425-432) argues that written productions should be investigated as parts of wider cultural systems, and these investigations fitted into a developing ethnography of communication. Basso suggests the personal letter in American society as a subject to be used in mapping out an emergent ethnography of writing. This essay focuses on another kind of non-specialist written production, the small town newspaper, and seeks to identify semiotic/semantic features of that genre which advance the ethnography of writing. 5 4 The study on which the essay is based involved several intensive months of meticulous examination and coding of newspapers from eighteen communities in western Montana.6 During the study, two research associates, William Dakin and Susan Boyd of the University of Montana7, and I were struck by the intriguing relationships that appeared to exist between a community and its newspaper. Implications of those relationships bear directly on current theoretical discussions in anthropology and folkloristics and need to be examined before presenting the empirical results of the study. The empirical presentation is intended to serve mainly a heuristic purpose; it will be enough if the analytical procedures employed here and the semiotic/semantic properties identified substantiate the crucial nature of the following general remarks. II First of all, what is one to make of a first brush with community newspapers of western Montana? For the most part, they are published in towns that by national standards are small and isolated in the extreme. A community of 1500 or 2000 persons is likely to be a county seat, the center of commerce and government, separated from the nearest town of comparable size by forty or fifty miles of highway that cuts through the Rocky Mountains and makes travel, particularly during the winter months, an experience. In the simplest geographical sense, the western Montana town is a true community, quite distinct from the “municipalities” that cluster around metropolitan areas, one shading imperceptibly into the next. In this setting of rural isolation, most community members know one another by sight, know their family ties, business interests, religious views, and gossip about the rest. Besides this wealth of knowledge, often garnered beginning in early childhood and extending into old age, the resident of the western Montana town is supplied with news about state, national, and world affairs from a variety of media — major Montana newspapers (such as the Great Falls Tribune and the Missoulian, each serving the region surrounding its city of publication)8, radio, television, and national magazines (such as Time and Newsweek). Between these extremes, acknowledging neither the car outside Widow Jones’ house last night nor the intricacies of détente, is the town’s weekly newspaper. Filled with accounts of city council meetings, high school sports events, weddings, deaths, and bridge parties, the small town newspaper is a chronicle of public and semi-public life — “all news that’s fit to print,” in a sense that is probably close to that intended for the New York Times of an earlier day. The small town newspaper is filled with “news” of a particular kind, a kind distinguished, according to our hypothesis, in that it conveys a sense of community life, of the community’s distinctive nature. Framing our introduction to the subject in 5 these terms makes it possible to pose clearly the question at the heart of the study: What is the relation between a community and a local narrative account of its affairs? Asking this question leads directly to a consideration of the theoretical issues involved here. In addition to the problem of how oral and written narrative may be related, there is the overarching problem of how ethnographic and folkloristic approaches are to be integrated, if at all. Hendricks’ integrative efforts are helpful in approaching this problem, but his analyses of literary works are intended to expand the heuristic overlap of linguistics, folkloristics, and literary criticism, and leave the question of the narrative – community relation mostly unexplored. If one is dealing with community newspapers, however, it is practically impossible to ignore that relation, since the materials one works with are themselves narrative renditions of social events. Ethnography and folkloristics are mutually implicated because the newspaper, as a description and interpretation of events, is ethnography and, as a culturally-constrained narrative production (the Widow Jones is never exposed in the pages of the Mission Valley News), is folklore. In addition, it is impossible to ignore the resonance of ethnography and folkloristics over a wide range, since both are forms of metadiscourse. The question of how a narrative account of a community describes, clarifies, explains what goes on there is at the heart of every ethnographic study. Like the small town newspaper, the anthropological monograph is (among other things) an account of what particular people do, of what is noteworthy about their lives, and must be evaluated according to what it tells, or doesn’t tell, about them. As Geertz (1978) suggests, the monograph is a literary production; it is just that its scope greatly exceeds that we usually attribute to the community newspaper. Moreover, the monograph is largely a second-order, or meta-discursive, rendering of primary narrative materials. People tell the ethnographer things and he writes them down; people tell other people things which the ethnographer overhears and writes down; or the ethnographer observes people and their surroundings and writes down what he sees. Thus oral tradition, kinship ties, social activities, political affairs, agricultural practices, and the like are scrutinized through the infinitely complex lens of the written words that spread across the pages of an ethnographer’s field notebooks and eventual monograph. This is not to say that the ethnographer and the journalist pursue the same craft, but the disdain the former often feels for the latter’s work (occasionally dismissing it as impressions gleamed from eavesdropping at diplomatic cocktail parties) should not be allowed to spill over into a related problem area: How does the ethnographer handle narrative material produced by local journalists describing events in the fieldwork area? It is well enough to dismiss members of the international press corps, cooling their heels around hotel bars in the capital city of a Third World country, but the conscientious ethnographer cannot afford to ignore the (often wildly interpretive) 6 content of local publications, nor community members’ reactions to them. In considering that material, the ethnographer really must assume the interpretive role assigned him by Geertz. Something happens, someone tells a reporter about it, he writes it down, it becomes part of a story, gets edited (often by the reporter himself on a small town newspaper), is published, read, and perhaps even taken into account by readers in ways that are highly significant to the outsider who is trying to take all that, and much, much more into account in producing his own text about those readers and their culture. Metadiscourse, telling about telling, whether at one, two, three or more removes from the actual episode (and often the episode itself is a telling), is the stock-in-trade of both ethnographer and journalist, and it is what leads them, sometimes consciously for the former, perhaps less often for the latter, into reflecting on their respective crafts’ association with folklore and its interpretation. Unlike Sergeant Joe Friday, who only wanted “just the facts, ma’am,” the ethnographer knows (or should know) that there is no clear separation between what goes on in a particular situation and what people think and say about what goes on (and, if we follow Wittgenstein rather than Sergeant Friday, we may conclude that the saying is more accessible than the goings-on). It is the concern with interpreting the said, the Aussagen, that brings ethnography and folkloristics together. Telling a tale within hearing distance of a folklorist normally results in the production of a text, and even when the folklorist’s emphasis is on verbal performance9 there remains the important, if mundane, consideration that performance is rendered and discussed mainly in the pages of sparsely illustrated academic publications. Metadiscursive analysis is the very nature of folkloristic studies. Someone tells a story — myth, legend, humorous anecdote, or whatever — and the folklorist seeks to determine its significance. Depending on his interests, he approaches the text in terms of its internal narrative structure, its position within a corpus of texts, its sociocultural context, or some combination of these. Ethnographers of communication insist in principle on the embeddedness of texts in a cultural system, and consequently regard the three approaches mentioned here as necessarily interdependent. We submit that an especially nice example of this interdependence is to be found in the small town newspapers of our study. The case studies in Bauman and Sherzer (1974) pursue the theme of verbal performance as a sociocultural phenomenon; here we shall argue that those studies can profitably be extended to cover written folk productions as well. Our view that small town newspapers can be interpreted as folk productions requires elaboration, for, as we have come to understand, identifying the relation between a community and its newspaper rests on the concept of a human community itself as a group of speaking, hearing, understanding subjects. There is a potential difficulty in approaching small town newspapers as folk productions, for generally the 7 former are more closely associated with a discrete population than the latter. Myth, legend, riddles, and other traditionally conceived genres of “folklore” differ from newspaper stories in that they are presumed to be relatively free of context: the same traditional tale or a closely related variant often is told in widely separated and linguistically diverse speech communities. Even granting the important performative features of these tales which ethnographers of communication have identified, it is still clear that they lend themselves more readily to formal narrative analysis. For example, the value of Hendricks’ studies consists in demonstrating the heuristic range of structural analysis across the fields of oral and written literature. Can something like that be done for community newspapers? We suggest that, while a study of small town newspapers which restricted itself to discourse analysis would be helpful, it is better to begin by approaching them as texts firmly anchored in particular human communities. Unlike myth, newspaper stories are about particular persons and particular events (although it is an intriguing question whether, say, the premier of China is any more concrete to a western Montana logger than is a mythical demiurge to a South American Indian). The folkloric quality of newspaper stories consists less in their formal narrative properties than in their authors’ acceptance of a whole set of assumptions about what “news” is and how it is to be reported. Since the basic issue here is the relation of a community to its narrative, we are led to the view that an analysis of a newspaper narrative is inevitably part of an analysis of a cultural system. It is crucial to be precise here. The approach to narrative-community relationships we propose differs significantly from that briefly indicated by Hendricks (pp. 143-144). His goal in bringing linguistics and folkloristics together is to get “beyond the sentence,” which for him involves emphasizing the distinction between a formal and a sociological analysis of texts. In the former approach, social order is thought to be “built into the stories” (page 143) in such a way that a formal analysis of narrative structure automatically says something about the organization of cultural themes in the community. In the latter approach, the community is presumed to exist “outside the stories as something assumed, which the analyst can then correlate with what is actually in the stories.” Our previous remarks about the western Montana newspaper suggest that this analytical dichotomy cannot be maintained in practice, and that in its place an integral concept of the narrative-community relationship is required, one which combines ethnographic and folkloristic perspectives. The formal approach is inadequate because newspaper narrative is interpretive, and so “builds in” the community only in a complex sense. It is assuredly not an isomorphic reflection — a kind of Malinowskian charter — of social relations. The sociological approach is even wider of the mark for it assumes that a sociocultural order — the community — can somehow be given form independently of accounts of it. This formulation is 8 inadequate to the task before us, for we are not dealing with two things here — a group of communities and a set of narratives about them — but with a single system of significations which are not merely attached to particular human groups, but constitutive of them. A human community is a semiotic construction; it implies and is implied by narratives generated by its members. The outlines of an answer to the question regarding the relation between a community and its narrative productions are now in sight. The prosaic documents of our study illustrate, probably better than other written narrative genres, the complex interconnections that tie language to culture and reconcile individual originality to the aesthetic and moral norms of society, III In attempting to combine ethnographic and folkloristic perspectives, we were immediately confronted with the problem of editorial originality. Our earlier suggestion that the eighteen newspapers in our sample are intimately tied to and representative of their localities of publication is the result of interviews we conducted with editors and staff of several of the newspapers. This ethnographic exercise, necessitated in any event by our virtually complete ignorance of journalism as a profession, produced much useful material on the process through which an editor survives, or goes under, in a small town. While the details of this process need not be examined here, it is essential to describe enough of it to show how the ethnographic investigations contributed to our present views. At the beginning of the interview series, we were primarily concerned with whether individual editors as practitioners of a skilled craft, operated for the most part according to a professional creed independent of the community. If this seemed to be the case, there would obviously be little point in pursuing the study of small town newspapers as folk productions. Since the interviews were conducted after considerable textual analysis of the newspapers had been done, we cannot pretend to a textbook objectivity in their execution and interpretation. Nevertheless, we were genuinely surprised at the extent to which community concerns and mores seemed to influence editorial policy. Despite differences in professional training and experience, the overarching reality in every case appeared to be the exigencies of life in a small town. Any small town resident, and particularly someone in the public service role of a newspaper editor, is constrained in both behavior and expression. This simple fact of coexistence, of having to interact with an assortment of community members on a daily basis, was expressed to us in one form or another by every editor we interviewed. One editor made the point most succinctly: 9 . . . I like running the paper, and I think it ‘s a pretty good one. But I’m not out to take on the town, just the opposite. This is where my family and I live, this is our home . . . It is important to recognize that this individual is not describing an adversarial standoff, but the importance his belonging to the community has on his role as editor. Decades of living and working in a town make an individual part of it, and encourage an easy accommodation between practices learned years ago in journalism school and the daily flow of existence. The importance of such an accommodation is more striking in its absence, as one interview with an embattled young newspaper editor demonstrated. That individual was fresh from a university school of journalism and had taken on the editorship of the local newspaper after moving to the town to discover rural America. Her predecessor, she said, had been a local housewife with a high school education (it was a small newspaper, even by Montana standards). Although she edited the paper, the final copy was reviewed by the publisher, who also owned another paper in a neighboring town. Inspired by investigative reporting and with Bernstein and Woodward as her models, she found the chronicling of horse shows, pinochle evenings, and municipal sewerage levies tedious. Still, she recognized the inherent limitations of the job and, needing the money, decided to stick it out. The months that followed were a lesson in the shaping of editorial behavior. Readers called or wrote to complain that obscure social events were not reported, the names of dinner guests omitted, or remarks at public meetings quoted when they should have remained “out of the paper.” Even with her policy of tailoring coverage to the community’s needs and desires, the editor found that each new issue brought a stream of unexpected criticism. At the time of the interview, she had about decided to resign her posittion. These interviews support our earlier observation that small town newspapers are difficult to classify as written narrative produced by specialists. While the editor is distinguished from other town residents as the holder of a specialized role involving verbal ability, competent performance of that role requires exacting attention to collective sentiment.10 The editor’s personality, political views, and even recreations (one editor in our study regularly published photographic essays of his vacations) may well affect paper content, but his livelihood depends entirely on community acceptance of the product. The editor as professional and as local businessman must be accommodated within the same person, and those editors one meets are generally individuals who have successfully carried this off. It is quite simply a matter of being of the community. 10 The question of editorial originality, of the editor’s supposedly specialized role, addresses an important issue in folkloristics: the dichotomy of creativity vs. convention in the production of narrative. To what extent is the verbal artist’s work primarily an expression of his individual talent and to what extent is it a statement of the common understanding? Our study adds a peculiar twist to this discussion, for its findings contradict the usual view that the oral narrator is more constrained than the writer by community sentiment. Bogatyrev and Jakobson (1929: 906) held that the “preventive censorship of the community” applied with more force to the teller of stories, who depended on immediate audience response, than to the writer, who could compose flagrantly antisocial works that need not see the light of day for years. Hendricks (page 85) rightly counters that oral and written works alike need to be examined as both individual and social creations. His point is particularly relevant to our study, since newspapers in rural Montana reverse the situation described by Bogatyrev and Jakobson by being much more subject to community censorship than is informal, oral gossip. What gets said in “street talk” (where the Widow Jones’ nocturnal activities are mercilessly dissected) would never appear in the “Local and Social” column of the town newspaper. It would probably be correct to extend this observation to U. S. society in general, since the written word carries a sharper sting — and greater legal jeopardy — than the spoken. The practice of putting out a community newspaper is actually an extreme example of the constraints on communicating at all: something new must be said for communication to occur, but the novelty of the account has to be compromised, firmly grounded in the already known and accepted. IV Our approach to the actual textual analysis of the eighteen newspapers in the sample was governed by a desire to build a framework for systematic comparison. If communities can be studied as intermeshed systems of signification, then their newspapers, as parts of those systems, should furnish information about similarities and differences among them. The overarching question here is whether the stories that people read about themselves are basically alike from town to town, or whether there are significant differences. If differences exist, these need to be documented and related to the sociocultural context in which they occur. Our initial assumption (call it an hypothesis if you like) was that significant differences are likely present and related in some fashion to intra-regional variations in western Montana society. While that region and, indeed, much of the mountain states area, may appear homogeneous to a metropolitan observer, residents in fact note social variations that are tied to readily documented demographic and economic conditions. We give here the barest outline of 11 those social variations, but urge that a full-blown attempt to combine ethnographic and folkloristic approaches in narrative analysis would require extensive fieldwork in the virtually unstudied communities. The communities are located in an eight-county region of northwestern Montana bordered by Idaho on the west and south, the Continental Divide on the east and Canada on the north. The terrain is more or less mountainous, with towns and roads laid out in the network of valleys cutting through the ranges of the Rockies. Although most settlements are small and isolated, there is one in the region (Missoula) that counts as a major city by Montana standards, with a population of about 55,000. The productive sector of the regional rural economy is concentrated in forest industries and ranching, with emphasis on the former. An increasingly important factor in the economy as well as in other social institutions is recreational and retirement property development. Topography dictates the economy of particular localities. Timber can be harvested on the slopes of all valley walls — subject to environmental regulations — but the floors of some valleys are so narrow and rock-strewn that agriculture is of minor importance. Only two valleys are broad and fertile enough to make ranching the predominant way of life, and in one of those (the Bitterroot), which is located near Missoula, residential subdivisions have sprung up in many pastures and fields. In the northern part of the region, around Glacier National Park, ski developments, a large tract of wilderness, and a large lake make tourism and retirement homes the major focus of local economies. Minimal ethnic diversity is present in the form of the Flathead Indian Reservation. The region’s 4,000 Native Americans comprise about 2.5 per cent of the total population of 157,000. All these demographic, economic, and ethnic variations are represented in the communities of our sample. Four issues of each paper, with comparable publication dates, were selected to provide a representative corpus. Rather than attempt detailed narrative analyses of a few selected portions of the papers, we opted instead for a broad-brush study of substantial portions of the content of each of the seventy-two papers.11 Detailed topical information was assembled for each article that fell into one of the following categories: every item on the front page; every “opinion” piece (letters, editorials) on the editorial page; the two longest articles in the rest of the paper; and the two largest advertisements on pages two and three of the paper. Using these criteria, we obtained specific data on fifteen to twenty-five articles for each issue of the seventy-two newspapers, for a total sample of 1,320 articles. This volume of material imposes restraints both on methodology and on the kinds of data that can be fitted into a comparative framework. Regarding methodology, it is immediately evident that flexibility in comparative procedures can be had only with computer processing. Our selection of a program was strongly influenced by a predisposition favoring the human coder over the machine. We feel 12 that computer-based analysis of narrative has a reasonable possibility of productive results if the machine is introduced only after professionally trained coders have read and prepared the material. The problem with machine reading, as we understand it, is simply that semantic rules cannot be written that will enable the most sophisticated program to scan a text and produce a useful summary of its message. The basic and apparently simple question, “What is this article about?”, can be answered in a few sentences by a literate human but not by a machine.12 With this in mind we opted for the FAMULUS program, which applies Boolean algebra to indexical studies of documentary collections. The program allows searches across ten information fields, all of which we utilized in the coding operation. All coding of substantive material was done by the three members of the research staff (Dakin, Boyd, and Drummond), who consulted with and cross-checked each other’s work to insure maximum consistency. Apart from labeling information which consumed four information fields (name of newspaper, title of article, and so on), the remaining six fields were used for the following kinds of substantive information: 1) 2) 3) 4) 5) 6) Type of article (news item, editorial, etc.). Topic area (politics, social affairs, economy, education, land use, community service, legal proceedings). Scope of article (local through international). Tone (editorial comment absent or present and, if present, affirmative or critical; also, whether the actual subject matter of the article was controversial or innocuous in the context). Value (dominant value(s) expressed or strongly implied in the article). Descriptor (ninety-one specific breakdowns of items in the Topic field into particular kinds of economic activities, decision-making institutions, voluntary organizations, etc. An important feature of the Descriptor field was the inclusion of an endorsement predicate _____restrict or _____ promote, which could be attached to any item in the field to indicate a significant change in its status. For example, a news item citing recent hospitalizations (a common feature in most of the newspapers) would receive, among others, the descriptor HEALTH, while an article on the probable closure of the local hospital would be coded HEALTH-RESTRICT).) Our textual analysis of the coded material aims at building a comparative framework on the basis of two considerations: 13 1) 2) If our hypothesis that a newspaper is part of a system of significations is at all sound, then the newspapers of different communities should reveal marked differences in the distribution of items in the substantive fields of Topic, Scope, Value, and Descriptor; A relatively few items in association should reveal semantic features of newspaper narrative that directly implicate sociocultura1 factors differentiating communities. Relevant portions of the distributional study are summarized in Table 1 and Figure 2. Table 1 simply demonstrates that there are significant differences among the newspapers in terms of the frequency with which items in the scope and topic fields get reported. Moreover, a brief examination confirms the fairly obvious fact that particular items co-vary: newspapers with a high percentage of national and international affairs articles have a low percentage of local affairs articles, and vice versa. Similarly, newspapers with extensive political and economic coverage have little social and community service news, and vice versa. Figure 2 presents the three newspapers with the highest and lowest frequencies of reporting for each category, and thereby reveals a correspondence between scope and topic content. See Table 1 and Figure 2 14 15 16 The Missoulian, Daily Inter Lake, and Hungry Horse News typically carry numerous national and international stories about political and economic affairs; they are also published in the three largest communities in the region (Missoula, Kalispell, and Columbia Falls). The Mission Valley News (Ronan), Northwest Tribune (Hamilton), and Whitefish Pilot (Whitefish) are distinguished by a concentration on local social affairs and community service activities. Like the legendary truck stop café, these correlations neither astonish nor disappoint: papers with large circulations print more “hard news”; papers with small circulations more “soft news”. Newspapers hold up the world for inspection by their readers, and if some are filled with accounts of Arab gunmen and disarmament talks while others run on about the Heart Fund and the high school basketball game, then these disparate panoramas form part of the cultural orders of the communities involved. Simple differences in content may well point to quite fundamental differences in lifestyle and outlook. The two “cities” in our sample (Missoula and Kalispell) are set apart from the logging towns and ranching valleys of the region in ways other than newspaper content; the two are poles in an urban-rural continuum which has complex meanings for the people involved. Ethnographic research supports this observation. Editors interviewed were quite explicit about differences between “hard news “ (politics and the economy) and “soft news “ (social affairs), and about the proper ratio of the two in their newspapers. One small town resident not connected with a newspaper provided an interesting, and unsolicited, confirmation of the difference between his town’s newspaper and one of the regional papers: I read the Missoulian sometimes, but it doesn’t tell me what’s going on here . . . who got married, who died, and what Penneys has on sale. I guess it’s got more news, but it’s just not my paper. Distributional analysis provides clues to understanding what makes a newspaper of the community. However, more substantive indications can be gained from a thematic analysis of associations in newspaper content that appear to be tied to sociocultural differences. We now turn to a consideration of those associated themes. The following abbreviated presentation is intended primarily as a heuristic device to identify thematic features of western Montana narrative and culture. Central to this discussion is the notion of the newspaper as a forum for community sentiment and debate. Following on our earlier claim regarding the interpretive nature of 17 newspaper narrative, it would be inaccurate to claim that newspaper A consistently presents image A of the community, newspaper B image B, etc. We feel that, while this is true to some extent15 it is important to recognize that what gets left out of a newspaper — or what is left unsaid of what is included — is also crucial to the narrative-community relationship. The set of significations a newspaper communicates is not always, or even primarily, “what goes on,” but what a community is prepared to read about itself and the outside world. To get at distinctions on this plane requires a close reading of the texts. Semantics figures at every turn, making the trained human reader/coder indispensable. The thematic analysis presented here turns on two pairs of oppositions in the Tone and Descriptor fields: CONTROVERSIAL/INNOCUOUS subject matter; and the endorsement predicates, ____PROMOTE/____RESTR1CT. The newspaper as forum places community members in a larger social milieu in several ways. Sensitive issues, those with a sting, can be confronted or skirted. This is the essential point behind the Tone opposition, CONTROVERSIAL/INNOCUOUS. These categories are not the same as the “hard news” vs. “soft news”, political-economic vs. social affairscommunity service oppositions in Topic distribution. The difference is intimately tied to context, and hence semantics. One city council meeting (a “hard,” political event) can be a ho-hum affair of budgeting for a new police car or granting building permits, while another can be (as in an actual case) a scene of bitter conflict over imposing a dog ordinance (or, sometimes, a horse or fowl ordinance) where none existed before. Articles that describe events without mentioning or strongly implying their (potentially) controversial nature were thus coded INNOCUOUS, and the others CONTROVERSIAL. Another aspect of the newspaper as forum is seen in its stance toward social change. With increasing demands on its forest, water, and mineral resources by a government bent on national self-sufficiency, and with increasing numbers of urban refugees moving in (the “Californication” of Montana), changes in western Montana are occurring rapidly. The endorsement predicates ____PROMOTE/____RESTRICT in the Descriptor field represent our attempt to categorize the orientation of newspaper narrative to social change. For an endorsement predicate to be applied to a particular descriptor, say TOURISM or ENERGY, the article must describe a state of affairs in which the activity is likely to be enhanced or diminished. Absence of an endorsement predicate for any descriptor in the article (as in the majority of cases) indicates a neutral orientation to the activity narrated. We submit that the frequency and type of endorsements indicates something about a community’s orientation to social change. The newspaper as a forum for confronting change falls between two extremes: the paper either accepts or rejects changes in important areas of local social life. Obviously, not all ____PROMOTE 18 predicates endorse change, nor do all ____RESTRICT predicates reject it. The status quo is often championed in the small town newspaper, as evidenced by ____RESTRICT predicates attached to the descriptors GUN CONTROL, SUBDIVISION, and TAXES. Similarly, these status-maintaining ____RESTRICT functions may occur in company with PROMOTE predicates for the descriptors, FARMING and GRAZING. Following this line of thought, we identified a thematic opposition that complements and crosscuts the CONTROVERSIAL/INNOCUOUS opposition, and labeled it CHANGE POSITIVE/CHANGE NEGATIVE. Here the program’s facility for Boolean operations proved indispensable, for it was necessary to construct search formulae of up to twenty-two terms. The procedure yields dual semantic continuua, with newspapers laid out along the resulting matrix according to the degree to which social change is actually or implicitly encouraged or rejected. The salient difference here is basically between newspapers that convey a sense of preserving a rural lifestyle in the face of external pressure to change, and newspapers that adopt a responsive, even eager attitude, toward development. The elements of our comparative framework are now complete. Combining the two semantic axes yields the paradigmatic array in Figure 3. See Figure 3 19 20 The coordinates of the newspapers on the semantic axes indicate their relative tendency to air sensitive issues and, usually among these, to confront issues of social change. The two axes are complementary, with a wide range along one vector and a fairly narrow range along the other. The paradigm in Figure 3 does not conflict with the order of newspapers according to Topic distribution (Figure 2), but it does add significantly to it by grouping newspapers according to thematic properties. Identifying these makes it possible to discern something of the relation between ethnographic and folkloristic approaches to written narrative. Communities whose newspapers lie to the upper right of the intersecting median points are all either the large towns or logging towns, or both (that is, towns where the health of commerce is synonymous with the state of forest industries). The high incidence of endorsement predicates assigned to controversial issues in those newspapers creates an accurate impression of the communities’ typically engaged stance vis-à-vis government, environment, and economy. According to our narrative analysis, timber workers and townspeople have something in common, which contrasts with other members of western Montana communities. The latter are predominantly ranchers and retirees — including those young or middle-aged “retirees” who have opted out of urban U.S. society — and it is significant that these groups, along with Native Americans, make-up the population of towns with newspapers in the lower left-hand quadrant of the paradigm. Those newspapers evince a strong internal focus, and project an image of the community as an expressive, uncomplicated world of school functions, social events, and the like. V While our narrative analysis could be extended, enough has been presented to show that the community-narrative relationship is significant and merits close attention in future studies of written narrative. Enquiries that pursue ethnographic and folkloristic lines simultaneously offer many possibilities for cross-fertilization. Some of our previous ethnographic work (Drummond et al 1975) suggests that cultural themes in western Montana fit into a scheme familiar to students of narrative: the triangle. There is empirical support for the view that we are not dealing here with yet another refrain of the rural/urban dichotomy, but rather with a triadic scheme of 21 complementary and opposed elements. In the communities of our study, these elements are symbolic and behavioral constellations tied to the three principal modes of life: ranching, logging, and town life or retirement (see Figure 4). The thesis, which we cannot develop fully here, is that these activities serve as the nuclei of cultural themes that make themselves felt throughout the institutional fabric of society — in family life, kinship ties, school activities, political orientation, land use, recreation, and more. If this interpretation has any validity, then the thematic comparisons developed in our narrative analysis support an approach to folklore much like that Bauman (1972: 31-41) espouses: folklore is not to be understood as the singular possession of distinct folk groups, but as interacting performances (and, we would add, narrations) among groups. According to this view, as we employ it here, human groups tell themselves and others stories about their respective identities, and only through that complex process of intertelling and interacting do they constitute themselves, laying claim to boundaries that are always conceptual, always shifting, always contested. Western Montana ranchers, loggers, and townspeople have roots in a history and stakes in a future that are given form only through a long, involved, and inherently contradictory process of mutual interaction and interpretation. Their combined stories yield up composite identities that are not internally consistent, nor do they clearly differentiate one identity from another. They are vectorial movements in a 22 multidimensional cultural space. This critical process is carried out, in part, in the mundane forums of the Tobacco Valley News, the Plainsman, and the Ronan Pioneer. An adequate understanding of how their narratives enter into the live of western Montanans requires developing an ethnography of the communication of cultural identity. 23 Notes 1. Instances are to be found in Bogatyrev and Jakobson (1929) and Abrahams (1969). 2. Hendricks (p. 83) with Ben-Amos (1971) and Hymes (1962). 3. Following Labov and Waletzky (1967). 4. For illustrative works, see Bauman and Sherzer (1974), Gumperz and Hymes (1972), Labov (1970), and Fishman (1975). 5. It may appear mistaken to call any newspaper a “non-specialist” production, since its contents are the work of trained individuals with specific roles in the community. Discussion of this point must await the following discussion of convention and creativity. For now it is enough to note that contributors to a small town newspaper are often formally untrained in journalism, and that even a journalism school graduate produces, in the role of weekly newspaper editor, a product discernibly different from that of an urban newspaper reporter. 6. The Institute for Social Research, University of Montana, assisted materially and intellectually by making available facilities and staff and by providing, through its director, Raymond Gold, a marvelous sounding board for ideas. The project was funded by the U. S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service. 7. As noted throughout this essay, William Dakin and Susan Boyd, graduate students in anthropology at the University of Montana, contributed substantively to every phase of he project. Their individual assistance and ideas are here gratefully acknowledged. 8. The Missoulian is located in the project survey area and is included in the study. The Great Falls Tribune, published in Great Falls, is across the Continental Divide from the survey area and is not included. 9. As, for example, in Bauman (1975). 24 10. A lively forum for individual criticism does exist in another narrative genre present in the small towns of our study. This is the “street talk” that occurs among residents while shopping in the downtown area, picking up their mail at the post office, sitting in the town’s one or two beauty parlors, hanging out at the drive-in, drinking in the bar. The editor, like everyone else with public visibility, is routinely monitored by “street talk” and, if he is at all astute, uses it as a guide in his reporting. 11. We feel this generalized search for comparisons is justified by the exploratory nature of the study. Not knowing which features of newspaper narrative would prove distinctive, it was important to cast as wide net as possible. Still, fascinating work could be done on structural narrative analyses of such forms as the wedding announcement, the obituary, and the sports article, 12. For an excellent critique of the current state of content analysis in social research, see Markoff et al (1974). 13. Interestingly named, a famulus being the secretary of a Medieval scholar. 14. For a discussion of these values and their method of identification, see Rokeach (1973). 15. For example, newspapers with extensive coverage of high school sports and local weddings probably do reflect rather strong community interest in such events. 16. For variations on this theme, see Olrik (1965) and Lévi-Strauss (1966) . 25 References Cited Abrahams, Roger 1969 The Complex Relations of Simple Forms, Genre 2; 125-126. Basso, Keith 1974 The Ethnography of Writing. In Explorations in the Ethnography of Speaking. Richard Bauman and Joel Sherzer, Eds. pp. 425-432. Bauman, Richard 1972 Differential Identity and the Social Base of Folklore. In Toward New Perspectives in Folklore. Americo Paredes and Richard Bauman, Eds. Austin: University of Texas Press. 1975 Verbal Art as Performance. American Anthropologist 77: 290-311. Bauman, Richard and Joel Sherzer, Eds. 1974 Explorations in the Ethnography of Speaking. New York: Cambridge University Press. Ben-Amos, Dan 1971 Toward a Definition of Folklore in Context. Journal of American Folklore 84: 8-9. Bogatyrev, P., and Roman Jakobson 1929 Die Folklore als eine besondere Form des Schaffens. In Donum natalicium Schrijnen. Nijmegen-Utrecht: Dekker. Drummond, Lee, William Dakin, Susan Boyd 1975 Conflict and Complementarity in the Lifestyle of a Montana Valley. Department of Anthropology, University of Montana. Fishman, Joshua A. 1975 The Sociology of Language: Yesterday, Today and Tomorrow. In Current Issues in Linguistics Theory: Invited Lectures at the 1975 Summer Linguistics Institute. Roger Cole, Ed. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, Geertz, Clifford 1973 Thick Description: Toward an Interpretive Theory of Culture, In The Interpretation of Cultures. New York: Basic Books. Gumperz, J. J., and D. Hymes, Eds. 1972 Directions in Sociolinguistics: The Ethnography of Communication. New York: Holt, Rinehart and Winston. Hendricks, William 0. 1973 Essays on Semiolinguistics and Verbal Art. The Hague; Mouton. Hymes, Dell 1962 Review of Indian Tales of North America, by Tristram P. Coffin. American Anthropologist 64; 688. Labov, William 1970 The Study of Language in its Social Context. Studium Generale 23: 30-87 Labov, William and Joshua Waletzky 1967 Narrative Analysis: Oral Versions of Personal Experience. In Essays on the Verbal and Visual Arts. June Helm, Ed. Seattle: University of Washington Press. Lévi-Strauss, Claude 1966 The Culinary Triangle. Partisan Review 33: 586-595. Markoff, John, et al 1974 Toward the Integration of Content Analysis and General Methodology. In Sociological Methodology 1975. David R. Heise, Ed. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass Publishers. Olrik, Axel 1965 Epic Laws of Folk Narrative. In The Study of Folklore. Alan Dundes, Ed. Englewood Cliffs, N.J.: Prentice-Hall. 27