Chapter 1 Overview

advertisement

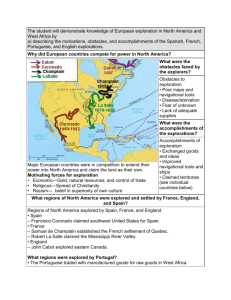

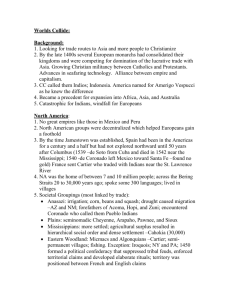

CHAPTER 1 Alien Encounters: Europe in the Americas CHAPTER OVERVIEW Columbus’s Great Triumph—and Error. Although Columbus failed to grasp the true significance of the discovery (he believed that he had reached Asia), he had reached two continents that Europeans had not known existed. Europeans had long valued Asian products such as spices, tropical fruits, silk, and cotton; and Columbus had hoped to find a western route to China, Japan, and the Indies, which would eliminate both the danger and expense of overland travel, as well as Italian middlemen. By the fifteenth century, western Europeans set about discovering direct routes to the East. Prince Henry of Portugal sponsored improvements in navigation and voyages of exploration. Columbus intended to reach China by sailing west into the Atlantic. About two o’clock in the morning of October 12, 1492, a sailor on the Pinta spotted land. He had spied an island in the West Indies called Guanahani by its inhabitants. The ship’s master, Christopher Columbus, went ashore bearing the flag of Spain and named the land San Salvador. Columbus did not know it, but he had landed on islands off the coast of two continents. His voyage opened up a new world to exploitation by the people of Western Europe. When he touched land, he refused to accept the overwhelming evidence that he had encountered not Asia but a world unknown to either Europe or Asia. He called the natives Indians, because he believed that he had reached the Indies. Columbus returned to Spain convinced that he had explored the edge of Asia. Three subsequent voyages failed to shake his conviction. Spain’s American Empire. By the time Columbus died in 1506, other captains had embarked on ventures of discovery and conquest. In 1493, the Pope had divided the non-Christian world between Spain and Portugal. Portugal concentrated on Africa, leaving the western hemisphere, except for what would eventually become Brazil, to Spain. Fifty years after Columbus’s first landfall, Spain held a huge American empire covering all of South America, except Brazil, and extending to the southern fringe of North America. Explorers such as Vasco Nuñez de Balboa and Ferdinand Magellan expanded geographic knowledge. Hernan Cortes and Francisco Pizarro subdued the Aztec empire in Mexico and the Inca empire in Peru. A distinct civilization emerged in the Spanish Americas. The Spanish founded cities, set up printing presses, constructed cathedrals, and established universities. The Spanish and other Europeans encountered natives in the course of their voyages of exploration. Greed and cultural arrogance led them to cheat and abuse those peoples with whom they came in contact; European technological superiority, particularly in instruments of war, provided the tools of domination. Even some contemporary observers, such as Bartolome de Las Casas (a Dominican missionary who arrived in Hispaniola roughly a decade after Columbus), were appalled by the barbarity of the conquistadores. While Spanish military leaders and administrators imposed an economic and social system based on Spanish feudalism, Catholic missionaries attempted to impose Christianity and obliterate native religious practices. Extending Spain’s Empire to the North. Within two decades after Columbus’s first voyage to the Americas, Spanish explorers had fanned out through the Caribbean and over large parts of the two continents that bordered it. Hernando de Soto traveled north from Florida to the Carolinas, then west to the Mississippi River. Francisco Vasquez do Coronado ventured as far north as Kansas and as far west as the Grand Canyon. By the end of the sixteenth century, the Spaniards learned that it was more profitable to acquire the crops and labor of Indians than search for rumored cities of gold. Don Juan de Onate led an expedition of Spanish colonists and soldiers across the Rio Grande into the territory of the Pueblo Indians, a farming people. Onate proved especially savage in his attempts to subdue the Pueblo. Franciscan missionaries baptized thousands of Indians and instructed them in the rudiments of the Catholic faith. They also taught Indians to use European tools, to grow wheat and other European crops, and to raise chickens and pigs. In the 1670s, a massive uprising by the Pueblo drove the Spanish back to El Paso. In the mid-1690s, the Spanish regained control of most of the upper Rio Grande. By the early 1700s, Spain had established a vast empire, but the population of the people they had subjected declined rapidly. Disease and Population Losses. Native American populations declined disastrously after the arrival of Columbus. Europeans brought diseases, such as smallpox, measles, bubonic plague, diphtheria, influenza, malaria, yellow fever, and typhoid, to the western hemisphere. These diseases had ravaged the populations of Europe, Africa, and Asia for centuries; by the 1500s, the populations of those continents had developed resistance to those diseases. American Indians, however, had evolved without contact with these diseases and therefore lacked biological defenses. When exposed to these diseases, whole communities of Indians died. It is impossible to calculate the mortality from disease among Indians, but the lowest estimates begin in the millions. Ecological Imperialism. So many Indians succumbed to Eurasian microbes, at least in part, because they were already suffering from malnutrition. Unconstrained by microbes or predators that had checked their populations in Europe, animals brought by the Europeans reproduced rapidly. They devoured crops grown by the Indians. Europeans also brought plants and with them weeds that choked out Indian crops. This left the Indian population even more vulnerable to disease. Though harmful to Indians, the biological exchange also brought benefits. Horses originated in the Americas but had become extinct in the western hemisphere by the time Europeans arrived. The animals thrived in the grasslands of North America, and the Plains Indians quickly adapted their lifestyles to take advantage of the horse. Some Indians raised sheep and wove woolen cloth. The biological exchange went both ways. Europeans contracted syphilis, a disease native to the western hemisphere, and brought it back to Europe. Plants native to the Americas, such as maize and potatoes, produced half as many calories per acre as traditional European crops like wheat, barley, and oats. Spain’s European Rivals. Spanish colonization reaped an enormous harvest of precious metals. Spain dominated exploration of the Americas during the sixteenth century, largely because it had established internal stability, whereas other countries were still torn by religious and political conflicts. Moreover, Spain seized those areas in the Americas best suited to producing quick returns. Spanish power seemed beyond challenge, but, in fact, the great empire was in trouble. Corruption, dependence on gold and silver from its colonies, and the disruption of the Catholic Church undermined Spanish power. The Protestant Reformation. Corruption in the form of the sale of indulgences and the luxurious lifestyles of the popes led to a challenge by reformers such as Martin Luther and John Calvin. Political and economic motives led German princes and Swiss cities to support the reformers. In England, Henry VIII’s search for a male heir led him to split from Rome when the Pope refused him a divorce. English Beginnings in America. Queen Elizabeth supported the explorations of English jointstock companies and encouraged privateers, such as Sir Francis Drake, to plunder Spanish merchant shipping. She also supported schemes to colonize the New World. After Sir Humphrey Gilbert failed to found a colony in Newfoundland, his half-brother, Sir Walter Raleigh, landed a group of settlers on Roanoke Island in 1587. Return supply ships did not arrive until 1590, and they found no sign of the “lost colony.” Angered by English attacks on his shipping, Philip II of Spain organized a great armada to invade England. The English fleet and bad weather destroyed the armada. Thereafter, Spain could not block English penetration of the New World. Queen Elizabeth, however, remained cautious. Not until after her death did full-scale efforts to found English colonies begin, and, even then, the organizing force came from merchant capitalists, not the Crown. The Settlement of Virginia. The London Company established the first permanent English settlement in America at Jamestown in 1607. The settlement almost was not permanent. Half the settlers died during the first winter because of mismanagement, ignorance of their environment, and a scarcity of people skilled in manual labor and agriculture. The London Company encouraged useless pursuits such as searching for gold rather than building a settlement. The settlement survived in part because Captain John Smith recognized the importance of building houses and raising food. Aid from Native Americans, the settlers’ realization that they must produce their own food, and the introduction of tobacco as a cash crop saved the colony. After accepting aid from the Indians, the English settlers took whatever else they wanted by force. The English at times behaved as cruelly as the Spanish, and, in defending their way of life, Indians committed atrocities of their own. The London Company invested huge sums in Virginia but never earned a dividend, and its settlers suffered a staggering rate of mortality. James I revoked the London Company’s charter in 1624, and Virginia became a royal colony. “Purifying” the Church of England. Under Elizabeth I, the Church of England became the official church. Her “middle way” satisfied most people. Catholics who could not reconcile themselves left the country; others practiced their faith in private. More radical Protestants, known as Puritans, objected to the rich vestments, the use of candles, and the use of music in services. Puritans’ belief in predestination also set them apart from the Anglican Church. Some Puritans, later called Congregationalists, also favored autonomy for individual churches. Others, called Presbyterians, favored an organization that emanated up from the churches rather than down from the top. Puritan fears that James I leaned towards Catholicism further alienated them from the Anglican Church. Bradford and Plymouth Colony. A group of English separatists set sail from Plymouth, England, on the Mayflower to settle near the northern boundary of Virginia. They landed north of their destination and decided to settle where they were. Since they were outside the jurisdiction of the London Company, they drew up the Mayflower Compact, a mutually agreed upon covenant that established a set of political rules. They elected William Bradford their first governor. With some help from Native Americans, they established a successful colony. Winthrop and Massachusetts Bay Colony. A group of Puritans formed the Massachusetts Bay Company and obtained a grant to the area between the Charles and Merrimack rivers. They founded Boston and several other towns in 1630. The founders established an elected legislature, although voters and members of the legislature had to be members of the church. Early on, the settlement struggled. Like their counterparts in the South, the settlers found creating a new society in a strange land more difficult than they had expected. However, luck, careful planning, and an influx of new settlers ensured the success of the settlements. Under Charles I, Puritans were persecuted in England, and the Great Migration of Puritans to Massachusetts Bay took place in the 1630s. Troublemakers: Roger Williams and Anne Hutchinson. Several groups dissented from the way the Massachusetts Bay colony was run. Roger Williams opposed the alliance of church and civil government and championed the fair treatment of Indians. Banished from the colony, he founded the town of Providence and later established the colonies of Rhode Island and Providence Plantation. Anne Hutchinson preached that those possessed of saving grace were exempt from rules of good behavior. The General Court charged Hutchinson with defaming the clergy, brought her to trial, and banished her. Hutchinson and her followers left Massachusetts for Rhode Island in 1637. Other New England Colonies. Congregations from Massachusetts settled in the Connecticut River valley. A group headed by Reverend Thomas Hooker founded Hartford in 1836. Their instrument of government, the Fundamental Orders, did not limit voting to church members. Pequot War and King Philip’s War. English colonists in New England repeatedly exploited divisions among Indians, who identified with their hunting group, rather than a tribe. New England saw two major Indian uprisings in the seventeenth century; in both, the English colonists prevailed in part because of the assistance of Indian allies. The first of these uprisings came in the 1630s, by which time the stream of English settlers to southeastern Connecticut had come to alarm the Pequot Indians. After several clashes in 1636, the colonists demanded that the Pequots surrender individuals responsible for attacks on the colonists and payment of tribute. When the Pequots refused, the governments of Massachusetts, Connecticut, and Plymouth declared war. Aided by warriors of the Narragansett and Mohegan tribes, which were traditional enemies of the Pequots, the colonists attacked a Pequot village. The subsequent massacre of the Pequots horrified the Narragansett and Mohegan. The second major uprising came in 1675, after the Plymouth colony had convicted and executed three Wampanoags. In response, Metacom, a Wampanoag sachem, led an uprising against the English settlers in New England, during the course of which about a thousand Puritans were massacred. The next year, colonists, bolstered by Mohawk allies, retaliated. The New England militias destroyed Wampanoag villages, and the Mohawks ambushed and killed Metacom. The Wampanoag retreated to the Great Swamp in Rhode Island, where they built a fort, which the colonists surrounded and burned. Maryland and the Carolinas. In the seventeenth century, English colonization shifted to proprietary efforts. Proprietors hoped to obtain profit and political power. Realities of life in America, however, limited both their control and their profits. Maryland, one of the first proprietary colonies, was established under a grant to the Calvert family. Lord Baltimore hoped not only to profit but to create a refuge for Catholics. Catholics remained a minority in the colony, however, and Baltimore agreed to the Toleration Act, which guaranteed freedom of religion to all Christians. A huge grant of land south of Virginia established Carolina, the proprietors of which drafted, with the help of John Locke, a plan of government called Fundamental Constitutions. Two separate societies emerged in Carolina. The one to the north was poorer and more primitive. The Charleston colony to the south developed an economy based on trade in fur and on the export of foodstuffs. Eventually the two colonies were formally separated. French and Dutch Settlements. England was not alone in challenging Spain’s dominance in the New World. The French planted colonies in the West Indies and, through the explorations of Cartier and Champlain, laid claim to much of the Saint Lawrence River area. Cartier attempted to found a French colony at Quebec in the 1530s, but it succumbed to brutal winters and Indian attacks. At the end of the century, French traders began to trade metal knives and hatchets as well as woolens with Indians for furs. Although there were only a few hundred French colonists in New France by 1650, the French government began to build forts to protect its toehold in North America. French and English colonization came into conflict that led to bloody warfare between the British and their Indian allies and the French and their Indian allies. The Dutch also established themselves in the Caribbean and founded the colony of New Netherland in the Hudson Valley. The Middle Colonies. The British eventually ousted the Dutch from New Amsterdam, which became New York. Quakers settled in New Jersey and Pennsylvania, where they drafted an extremely liberal constitution that guaranteed settlers freedom of conscience. William Penn, proprietor of Pennsylvania, treated the Indians fairly and permitted freedom of worship to all who believed in God. Penn’s ideas were more paternalistic than democratic. Cultural Collisions. Since the Indians did not worship the Christian God, the Europeans dismissed them as heathens. Some even regarded the Indians as servants of Satan. Conflicts grew out of cultural misunderstandings. Europeans assumed that Indian chiefs ruled with the same authority as their kings. Indians, bound more by kinship loyalties rather than allegiance to one leader, did not always honor commitments made by their chiefs. Europeans regarded this as treachery. Those Indians who depended on hunting and fishing had little use for personal property that was not easily portable. The European drive to amass possessions puzzled the Indians. Similarly, Indians regarded the cultivation of crops as women’s work and looked askance at European men who worked hard in the fields. The apparent lack of concern for material things led the Europeans to conclude that the native people of America were lazy and childlike. The notion that Indians left the environment undisturbed is a myth. Indians cleared fields, burned forest underbrush, diverted rivers, built roads and settlements, and constructed earthen mounds. Europeans, however, left an even deeper imprint on the land through their technology and imported animals. Cultural differences manifested themselves in warfare, too. Indians did not fight to destroy an enemy but to display valor or acquire captives. They preferred to ambush an opponent and seize stragglers. Europeans preferred to fight in heavily armed masses and to obliterate the enemy. Cultural Fusions. The relationship between Native Americans and Europeans is best characterized as an exchange. Indians taught the colonists how to grow food, what to wear, and new forms of transportation. Native Americans adopted European technology (especially weapons), clothing, and alcohol. Out of the interaction between cultures came something new and distinctively American. LEARNING OBJECTIVE QUESTIONS 1. What forces drove Europeans to exploration? 2. Why was England was relatively slow to explore and to settle the New World? 3. What European beliefs and attitudes governed their relations with Native Americans? 4. How did European and Native American concepts of land differ? 5. What was the impact of disease on Native American populations? 6. How did the Protestant Reformation influence the colonization of the western hemisphere? 7. Why was private exploration prominent in England and what were the consequences? 8. What problems confronted English settlement? 9. What was a proprietary colony? 10. What was the Columbian exchange?