SAH Pathway-APPROVED

advertisement

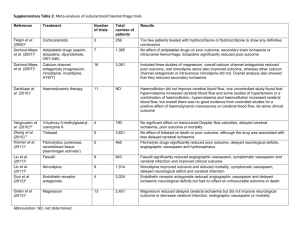

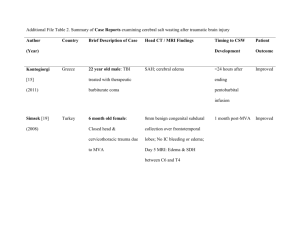

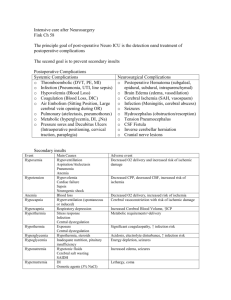

North Wales Critical Care Network SUBARACHNOID HAEMORRHAGE PATHWAY & CARE BUNDLE (for Adult patients requiring Critical Care) North Wales Critical Care Network [APPROVED] Amended March 2012. 1 North Wales Critical Care Network Adult Subarachnoid Haemorrhage Pathway and Care Bundle Introduction Early aggressive treatment of patients with a poor grade Subarachnoid Haemorrhage has resulted in favourable outcomes1. The aim of this paper therefore is to provide consistency across the North Wales Network region for Critical Care patients with a spontaneous Subarachnoid Haemorrhage (SAH). Because there are some differences in the management of spontaneous SAH patients from those with a Severe Brain Injury it was considered ‘safer’ to document their care separately. As with the Severe Brain Injury pathway however this document includes a referral pathway, ICU maintenance care and repatriation process for all SAH patients from the three hospitals, much of it being very similar. The first section provides a pathway and checklist for referral of the Subarachnoid Haemorrhage patient to the Walton Neurological Centre. This pathway has been agreed by Intensivists in North Wales with colleagues at the Walton Centre. The second section includes the guidelines that underpin the Subarachnoid Haemorrhage Care Bundle. This should be utilised for all Subarachnoid Haemorrhage patients who remain in the local ICUs. A quick guide of these more detailed guidelines is also included. The final section is a pathway for repatriating patients back to the local ICUs from Walton. North Wales Critical Care Network [APPROVED] Amended March 2012. 2 N Noorrtthh W Waalleess C Crriittiiccaall C Caarree N Neettw woorrkk Pathway for Referral of Adult Critical Care Patients with Subarachnoid Haemorrhage to Walton Neurological Centre Patient identified for referral to Walton Neurological Centre (CT/LP positive for blood) Immediate transfer not required Checklist complete (PTO) Referral to Neurosurgical SpR (0151 525 3611) Patient accepted (by neurosurgeons & intensivists) Handover to Critical Care staff (0151 529 5772) Image link CT Scan & inform Neuro SpR when CT sent Patient fully monitored Immediate transfer required (Ref Designed for Life: Welsh Guidelines for the transfer of the critically ill adult 2009) (Ref: All Wales Transfer Guidelines) Optimise patient for transfer Write discharge letter/plan & send with patient Contact Walton ICU (0151 529 5772) with ETA Call ambulance control (01248 689089) stating IMMEDIATE Transfer (Ref: Welsh Transfer Guidelines) Patient declined Admit locally to Critical Care Avoid secondary brain injury Initial resuscitation and stabilisation complete Walton to return call within agreed timescale (Ref: NICE CG56) North Wales Critical Care Network [APPROVED] Amended March 2012. Call ambulance control (01248 689089) stating URGENT Transfer Monitoring (during transfer) MUST include: ECG Invasive BP and NIBP SaO2 EtCO2 Temperature U/O by urinary catheter Pupillary size and reaction CVP where indicated Follow SAH Care Bundle Liaise with Walton Neurosurgical SpR re ongoing clinical management (Ref: NICE CG56) NB: Where transfer is necessary but Walton cannot accommodate the WCNN is responsible for finding a bed (SBNS). For Neuro ICU beds in the North West telephone ICBIS: 0161 720 2554 3 1 2 3 4 Referral Checklist - For Adult Subarachnoid Haemorrhage Patients to Walton Admitting DGH Consultant: Referring DGH Doctor: Referring DGH Consultant: Referring Hospital: Time of Call: Time of first contact Neuro SpR: Patient Details Name: Age: DOB: Sex: Brief description of SAH onset: 5 6 Time of onset: GCS, pupils and time of arrival on scene: 7 GCS, pupils and time of arrival at ED: 8 GCS, pupils at time of call: 9 Current observations at time of call: Any treatment given e.g. intubated / 10 Glasgow Coma Score Motor 6 Obeys Commands 5 Localises Pain 4 Flexes (withdraws) to Pain 3 Abnormal Flexion 2 Extension to Pain 1 No Movements Verbal 5 Orientated 4 Confused 3 Words Not Sentences 2 Noises Not Words 1 No Sounds Eyes 4 Open Spontaneously 3 Open to Voice 2 Open to Pain 1 Closed Time: Pupils: Eye Opening Motor Response Verbal Response Time: Pupils: Eye Opening Motor Response Verbal Response Time: Pupils: Eye Opening Motor Response Verbal Response HR: BP: SaO2 ventilated 11 Past medical history: 12 Is patient on Warfarin, Aspirin, or Clopidogrel? Reversal medication given e.g. Vitamin K, 13 Yes No Don’t know Yes No Don’t know Prothrombin Complex Concentrate (PCC) 14 15 16 17 18 19 Referral Clinician Tel No. & Ext No. Name of Neuro SpR spoken to: Name of Neurosurgical Consultant: Time of first contact with Neuro SpR: CT Scan report received and discussed with Neuro SpR: Outcome of call – comments: Yes PATIENT DECLINED No PATIENT ACCEPTED WHERE IS PATIENT TO GO TO? Walton Theatres Walton ICU Other: PLEASE TICK AS APPROPRIATE USEFUL TELEPHONE NUMBERS: Walton Switchboard: Walton ICU Phone: 0151 525 3611 0151 529 5772 Neurosurgical SpR: Walton ICU SpR: Ask switch to bleep Bleep 2018 PRIOR TO TRANSFER FAX THIS FORM TO WALTON ICU ON 0151 529 5510 North Wales Critical Care Network [APPROVED] Amended March 2012. 4 Subarachnoid Haemorrhage (SAH) Care Bundle (for adult patients requiring Critical Care) Background Information Nontraumatic spontaneous SAH usually is the result of a ruptured cerebral aneurysm or arteriovenous malformation (AVM). Blood extravasation into the subarachnoid space has a detrimental effect on both local and global brain function and leads to significant morbidity and mortality. Although mortality rates of SAH have decreased, it remains a devastating neurological problem. An estimated 15% of patients die before reaching hospital. Approximately 25% of patients die within 24 hours, with or without medical attention. The mortality rate at the end of one week approaches 40%. Half of all patients die in the first 6 months. Recent developments in neurocritical care including enhanced monitoring techniques, normalisation of pathophysiological states and better recognition and management of complications following subarachnoid haemorrhage have improved the level of care for SAH patients1. As a result mortality has decreased2,3. Advanced age, worse clinical grade, rebleeding, larger aneurysm size, global cerebral oedema, delayed cerebral ischaemia and medical complications all have a detrimental impact on outcome after SAH4-6. Reports of early and aggressive treatment of poor grade patients demonstrated unexpected improvements of long term functional outcome7-9. SAH is classified according to 5 grades: Glasgow Coma Score Grade I: Mild headache with or without meningeal irritation 15 Grade II: Severe headache and a no focal deficit Grade III: Severe headache with focal neurological deficit Grade IV: Depressed level of consciousness with or without focal deficit Grade V: Unconscious patient 13 or 14 13 or 14 7 to 12 3 to 6 World Federation of Neurological Surgeons. The ICUs in North Wales are familiar with the concept of care bundles; therefore a care bundle is described below to assist in the management of the subarachnoid haemorrhage patients who remain in the local ICUs. Subarachnoid Haemorrhage Care Bundle Early neurological and cardiopulmonary resuscitation of poor grade patients followed by high quality and comprehensive critical care should be the standard and based on a team approach1. This Subarachnoid Haemorrhage care bundle therefore aims to optimise care for the individual patient by addressing possible secondary cerebral insults and limiting ongoing brain damage. The three elements are: 1. Control of Intracranial Pressure (ICP) (caused by hydrocephalus and global cerebral oedema). 2. Optimisation of cerebral perfusion and oxygenation. 3. Prevention of aneurysm rebleeding; control of blood pressure, seizure prophylaxis. It should be noted that in order to be compliant with the elements in this bundle some elements of the Ventilator bundle may need to be excluded e.g. transfusion North Wales Critical Care Network [APPROVED] Amended March 2012. 5 guidelines and low tidal volume. Bundle Element 1 Control of Intracranial Pressure (ICP) In acute SAH the sudden rise in ICP up to the levels of MAP leads to an arrest of cerebral circulation which is clinically seen as loss of consciousness and to the development of global cerebral oedema. Cerebral oedema and the resultant cerebral hypermetabolism are linked to increased risk of death, disability and cognitive dysfunction4. Altered level of consciousness may also be related to haematoma formation, hydrocephalus, vasospasm, or reduced cerebral blood flow. Early detection of deterioration in the patient's neurological condition is essential for the prompt treatment of complications such as vasospasm, rebleeding and/or hydrocephalus. Patients with a SAH therefore require frequent neurological observations. Pupil size and reaction are paramount in the sedated ICU patient where sedation will prevent motor responses. If ‘deep’ painful stimuli are required this should be performed with supra-orbital pressure or trapezius squeeze10. Additional measures to prevent increases in ICP are also indicated; a. Perform Neurological Observations ½ hourly for 12 hours, hourly for 24 hours, then 2 hourly thereafter10 Clinician discretion will be needed after the acute phase. b. Avoid venous congestion head tilt 20-300 (preferably 300 but be mindful of compromising MAP and thus cerebral perfusion pressure) avoid external compression; use adhesive ETT tapes or loose tapes) avoid high thoracic pressures (adhere to bowel protocol). c. Control agitation / maintain adequate analgesia and sedation if intubated analgesia and sedation (local protocol) (if required) muscle relaxant with neuromuscular monitoring Bundle Element 2 Optimisation of cerebral perfusion and oxygenation There is often an imbalance in cerebral oxygen delivery and cerebral oxygen consumption resulting in tissue hypoxia11. A labile BP is common in high-grade subarachnoid hemorrhage. Hypotension must be avoided at all costs as it will cause a reduction in cerebral blow flow and will result in cerebral ischaemia12. Both hypoxia and ischaemia will increase ICP. Myocardial injury in patients with SAH occurs as a result of excessive sympathetic drive and catecholamine release. ECG abnormalities occur in approximately 35% of patients and a similar percentage of patients will also have an elevation of Troponin. Echocardiographic wall motion abnormalities occur in about 25% of patients. Significant pulmonary complications occur in approximately 20% of patients and this spectrum ranges from acute lung injury to pulmonary oedema. This may North Wales Critical Care Network [APPROVED] Amended March 2012. 6 complicate clinical management when trying to ensure adequate intravascular volume on one hand and trying to avoid pulmonary oedema on the other13. Cerebral vasospasm is a devastating medical complication of aneurysmal SAH that is associated with high morbidity and mortality rates. It is most likely to develop 312 days post SAH, lasting approximately two weeks and occurs in about two thirds of SAH patients, of which half will develop symptomatic cerebral ischaemia causing neurological deficit of varying severity. Cerebral vasospasm may also lead to increased ICP, secondary to infarction. Fever (>380C) is a frequent event in SAH patients and is associated with symptomatic vasospasm14 and an increased ICU and hospital length of stay15. Administration of oral Nimodipine improves outcome after SAH16. The oral (or NG) route has been shown to be just as effective as intravenous administration, but is associated with less hypotension. d. Nimodipine administration Administer Nimodipine to all SAH patients; 60mg orally every 4 hours, continued for 21days. If enteral route is not possible, consider IV infusion via CVP as per the British National Formulary; 0.02% (neat from vial into 50ml syringe) at 5-10mls/hr. NB use giving set supplied with the vial. Adequate cerebral oxygen delivery depends primarily on satisfactory cardiorespiratory performance, but can further be categorised by those aspects which need to be in place before transfer of oxygen from haemoglobin to the tissues occurs, namely; e. an adequate circulating volume Aim for: capillary refill <2 seconds CVP minimum 8mmHg1 using isotonic crystalloids 0.9% NaCl at 1.0-1.5 mls/kg/hr. consider hypertonic saline where hyponatraemia present (consider cerebral salt wasting) if u/o >4mls/kg consider treatment for Diabetes Insipidus NB: If problems with fluid or sodium balance advice from neuro-critical care Intensivist at ICU (Walton) can be sought 24hrs/day. f. adequate perfusion pressure Aim for: Systolic <160mmHg1, diastolic <110mmHg1 MAP >80mmHg o adequate filling (as above) Vasopressors as necessary12 Antihypertensives as necessary1 g. adequate oxygenation Aim for: SaO2 >93% pO2 >13kPa10,17 h. avoid hyperaemia Aim for: North Wales Critical Care Network [APPROVED] Amended March 2012. 7 CO2 4.5-5.0kPa10,17,18 i. control pyrexia maintain normothermia <370C1 (NB: Every 10C increase in core temperature causes a 6-10% increase in cerebral blood flow. The increase in cerebral blood flow causes an increase in cerebral blood volume therefore contributing to an increase in ICP). j. control hyperglycaemia maintain blood glucose 6-10mmol-1 (NB: Avoid hypoglycaemia at all costs) Bundle Element 3 Prevention of rebleeding; control of blood pressure, seizure prophylaxis. Rebleeding, a major complication, carries a mortality rate of 51-80%. It is hard to predict which patients will suffer a rebleed, yet it may happen at any time. After the first 24 hours have passed, rebleeding risk remains around 40% over the subsequent four weeks, suggesting that interventions should be aimed at reducing this risk as soon as possible. The main aim of treatment for SAH is prevention of rebleeding while preventing secondary ischaemia. Prolonged seizures may result in hypoxaemia and cerebral infarction due to cerebral hypoxia k. control of blood pressure (see also f – adequate perfusion pressure) Systolic <160mmHg1, diastolic <110mmHg1 o adequate filling (as above) see above note Vasopressors as necessary12 Antihypertensives as necessary1 l. control fitting Consider the context and requirement for induction of anaesthesia / intubation and ventilation If clinically indicated – Phenytoin 20mg/kg IV bolus followed by 5mg/kg daily1 (adjust dose according to plasma levels corrected for serum albumin); not exceeding 1.5 grams in 24hrs. m. Pharmacological thromboprophylaxis is generally contraindicated until the aneurysm is secured. Use Summary As well as optimising care of the SAH patient this care bundle should facilitate audit of process. Although compliance is expected, especially where deviations from this agreed practice cannot be justified, the bundle is not designed to replace clinician judgment. North Wales Critical Care Network [APPROVED] Amended March 2012. 8 Quick Guide for Subarachnoid Haemorrhage (SAH) Care Bundle Bundle Element Element 1: Control of Intracranial Pressure (ICP) Aims Pupillary reflexes performed minimum ½ hourly for 12 hours. Hourly for 24 hours, then 2 hourly thereafter. Avoid venous congestion Head tilt 20-300, preferably 300 Neutral head position Avoid external compression (consider use adhesive or loose ETT tapes) Avoid high thoracic pressures (adhere to bowel protocol). Control agitation/maintain adequate analgesia and sedation Element 2: Optimisation of cerebral perfusion and oxygenation Analgesia and sedation. (If required) muscle relaxant with neuromuscular monitoring. Administer Nimodipine to all SAH patients 60mg orally/NG every 4 hours, continued for 21 days. If enteral route is not possible, consider IV infusion via CVP as per BNF; 0.02mg/ml at 510mls/hr. Adequate circulating volume Capillary refill <2 seconds CVP minimum 8mmHg (zero at mid-axilla) using isotonic crystalloids 0.9% NaCl at 1.0-1.5 mls/kg/hr. Consider hypertonic saline where hyponatraemia present If u/o >4mls/kg consider Rx for D.I. Adequate perfusion pressure North Wales Critical Care Network [APPROVED] Amended March 2012. Rationale Pupillary reactions will provide prognostic information. Prompt detection of changes in size, shape and/or reaction of pupils any indicate swelling/an expanding lesion and increasing ICP. Head elevation will reduce oedema (and thus ICP) but >300 may reduce MAP and therefore CPP. Head rotation and neck flexion can increase ICP by impeding cerebral venous drainage. Tight ETT tapes will impede venous return. Straining will increase abdominal and thoracic pressures. Avoid ‘clustering’ care – stagger interventions giving time for ICP to settle in between. Sedation will help dampen the effect of any stimuli that might increase ICP. NB Beware of hypotensive effects of sedation, especially boluses. Exclusion Terminal care. EOL Care Pathway. Are all patients nursed Head elevated In a neutral position Patient does not require neuromuscular blockade Neuromuscular blockade may need to be considered if patient movement or ventilation remains problematic despite full sedation. It will also help to avoid rises in ICP due to coughing, straining etc. Administration of oral Nimodipine improves outcome after SAH. The oral (or NG) route has been shown to be just as Terminal care. effective as intravenous administration, but is associated with EOL Care less hypotension. Pathway. Maintenance of cerebral perfusion pressure (the variable which defines the pressure gradient driving cerebral blood flow) can be achieved with fluid replacement and inotropes (see below). Hyponatraemia occurs in 20-40% SAH patients as result of the syndrome of inappropriate excretion of anti-diuretic hormone (SIADH). Hypotension will result in a reduction in cerebral blood flow Compliance Audit Point Are there attempts to control ICP? Do all patients with a GCS less than 15 have Neurological observations performed as described? Are all patients adequately sedated and analgesed? Are there attempts to optimise cerebral perfusion and oxygenation? Do all patients have Nimodipine CVP minimum 8mmHg pO2 >13kPa MAP >80mmHg pCO2 4.5-5.0kPa 9 Systolic <160mmHg, diastolic <110mmHg MAP >80mmHg o adequate filling (as above) Vasopressors as necessary Antihypertensives as necessary Adequately filled (as above) Adequately oxygenated Hypoxia is the second most influential cause of secondary brain injury after hypotension and worsens outcome. Hypoxia causes vasodilation which will increase ICP. SaO2 >93% PaO2 >13kPa Avoid hyperaemia thus causing tissue hypoxia. Hypotension has been uniformly identified as the predominant factor in secondary brain injury and has highest correlation with morbidity and mortality. Hypertension Hypercapnia causes vasodilation which increases cerebral blood flow and volume and therefore ICP. pCO2 4.5-5.0kPa NB Beware low VT (e.g. Ventilator bundle causing an increase in PaCO2) Hypocarbia causes vasoconstriction which may exacerbate the risk of ischaemia. Control pyrexia Maintain normothermia < 37.00C Control hyperglycaemia Element 3: Prevention of rebleeding; control of blood pressure, seizure prophylaxis. Maintain blood glucose or 6-10mmol-1 (Avoid hypoglycaemia at all costs) Control of blood pressure (see also f – adequate perfusion pressure) Systolic <160mmHg, diastolic <110mmHg adequate filling (as above) Vasopressors as necessary Antihypertensives as necessary Control fitting Consider the context and requirement for induction of anaesthesia/intubation and ventilation If indicated; load with Phenytoin 20mg/kg IV bolus followed by 300mg/day* (adjust dose according to plasma levels corrected for serum albumin); not exceeding 1.5grams/24hrs. North Wales Critical Care Network [APPROVED] Amended March 2012. For every 10C increase in temperature there is a 10-13% increase in metabolic rate. Therefore pyrexia will exacerbate ischaemia. Shivering markedly increases ICP Hyperglycaemia may worsen cerebral ischaemia by decreasing cerebral blood flow. NB Beware of hypoglycaemia – the injured brain cannot tolerate it A labile BP is common in high-grade SAH. Hypertension increases the risk of re-bleeding however hypotension must be avoided at all costs as it causes a reduction in cerebral blow flow resulting in cerebral ischaemia. Patient does not require antiepileptics. Terminal care Seizure activity may cause rebleeding. It may also cause secondary brain injury as a result of increased metabolic demands, raised ICP and excess neurotransmitter release. Steps taken to reduce the risk of re-bleeding? Are all patients with SAH Normotensive Adequate control of fitting (where necessary) Or is there an attempt to achieve these parameters? 10 References: 1 Wartenberg K.E. (2011) Critical Care of poor grade subarachnoid hemorrhage. Current Opinion in Critical Care 17: 85-93. 2 Feigin V.L., Lawes C.M., Bennett D.A., Barker-Collo S.L. and Parag V. (2009) Worldwide stroke incidence and early case fatality reported in 56 population-based studies: a systematic review. Lancet Neurology 8:355-369 3 Taylor C.J., Robertson F., Brealey D., O'Shea F., Stephen T., Brew S., Grieve J.P., Smith M. and Appleby I. (2011) Outcome in poor grade subarachnoid hemorrhage patients treated with acute endovascular coiling of aneurysms and aggressive intensive care. Neurocritical Care. 14(3):341-7. 4 Claassen J., Carhuapoma J.R., Kreiter K.T., Du E.Y., Connolly E.S. and Mayer S.A. (2002) Global cerebral edema after subarachnoid hemorrhage: frequency, predictors, and impact on outcome. Stroke. 33(5):122532. 5 Frontera J.A., Fernandez A., Schmidt J.M., Claassen J., Wartenberg K.E., Badjatia N., Parra A., Connolly E.S. and Mayer S.A. (2008) Impact of nosocomial infectious complications after subarachnoid hemorrhage. Neurosurgery 62:80-87. 6 Wartenberg K.E., Schmidt J.M., Claassen J., Temes R.E., Frontera J.A., Ostapkovich N., Parra A., Connolly E.S. and Mayer S.A. (2006) Impact of medical complications on outcome after subarachnoid hemorrhage. Critical Care Medicine. 34(3):617-23 7 Le Roux P.D., Elliott J.P., Newell D.W., Grady M.S. and Winn H.R. (1996) Predicting outcome in poorgrade patients with subarachnoid hemorrhage: a retrospective review of 159 aggressively managed cases. Journal of Neurosurgery. 85(1):39-49. 8 Huang A.P., Arora S., Wintermark M., Ko N., Tu Y.K. and Lawton M.T. (2010) Perfusion computed tomographic imaging and surgical selection with patients after poor-grade aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage. Neurosurgery. 67(4):964-74 9 Haug T., Sorteberg A., Finset A., Lindegaard K.F., Lundar T. and Sorteberg W. (2010) Cognitive functioning and health-related quality of life 1 year after aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage in preoperative comatose patients (Hunt and Hess Grade V patients). Neurosurgery. 66(3):475-84; 10 UK National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence. Head injury: Triage, assessment, investigation and early management of infants, children and adults. (2007) http://www.nice.org.uk/nicemedia.pdf/CG56NICEGuideline.pdf Accessed 4th October 2007. 11 Werner, C. and Engelhard, K. (2007) Pathophysiology of traumatic brain injury. British Journal of Anaesthesia. 99(1):4-9. 12 Helmy, A., Vizcaychipi, M. and Gupta, A.K. (2007) Traumatic Brain Injury: intensive care management. British Journal of Anaesthesia. 99(1):32-42. 13 Diringer M N et al. (2011) Critical Care Management of Patients following Aneurysmal Subarachnoid Hemorrhage: Recommendations from the Neurocritical Care Society’s Multidisciplinary Consensus Conference. Neurocritical Care. 15:211-240 14 Naidech A.M., Bendok B.R., Bernstein R.A., Alberts M.J., Batjer H.H., Watts C.M. and Bleck T.P. (2008) Fever burden and functional recovery after subarachnoid hemorrhage. Neurosurgery. 63(2):212-7 15 Naidech A.M., Bendok B.R., Tamul P., Bassin S.L., Watts C.M., Batjer H.H. and Bleck T.P. (2009) Medical complications drive length of stay after brain hemorrhage: a cohort study. Neurocritical Care. 10(1): 11-9. 16 Pickard J., Murray G., Illingworth R., Shaw M.D., Teasdale G.M., Foy P.M., Humphrey P.R, Lang D.A., Nelson R. and Richards P. (1989) Effect of oral nimodipine on cerebral infarction and outcome after SAH: British aneurysm nimodipine trial. British Medical Journal. 298(6674): 636–642. 17 The Association of Anaesthetists of Great Britain and Ireland. (2006) Recommendations for the Safe Transfer of Patients with Brain Injury. London: The Association of Anaesthetists of Great Britain and Ireland. 18 Oertel, M., Kelly, D.F., Lee J.H. et al. (2002) Efficacy of hyperventilation, blood pressure elevation, and metabolic suppression therapy in controlling intracranial pressure after head injury. Journal of Neurosurgery. 97(5):1045-53. North Wales Critical Care Network [APPROVED] Amended March 2012. 11 N Noorrtthh W Waalleess C Crriittiiccaall C Caarree N Neettw woorrkk Pathway for Repatriating Patients Subarachnoid Haemorrhage to North Wales Hospitals from Walton Neurological Centre Intensive Care Unit Telephone numbers: Wrexham Maelor 01978 725447 or 01978 725608 Glan Clwyd 01745 534806 or 01745 534547 Bangor 01248 384244 or 01248 384436 Patient identified for repatriation to North Wales from Walton Neurological Centre Walton to contact referring hospital’s ICU (see ICU telephone no's red box opposite) Consider evidence of infection (where possible this should NOT delay patient’s repatriation) Yes Repatriate patient ASAP (to maintain ‘flow’ through Walton ICU) Bed available? No North Wales Critical Care Network [APPROVED] Amended March 2012. Discuss patient repat on daily teleconference – repatriate ASAP If no bed available liaise with Walton in 24hrs 12