A comparison of young citizens in Quebec, New Brunswick and

1

A Comparison of Young Citizens in Quebec, New Brunswick and

Alberta

Michel Pagé and Marie-Hélène Chastenay

Department of Psychology and GREAPE, Université de Montréal

In this presentation, we will offer a comparative analysis of the young citizens of three Canadian provinces: New Brunswick, Quebec, and Alberta.

This comparison is aimed at identifying both the points of similarity and the points of differentiation between the sample groups of the three provinces.

Here is a rapid description of these samples.

Comparative Chart of the Three Samples.

The same questionnaire was used for all three provinces, each version featuring the same number of items, although we obviously have had to adapt certain questions, for instance, when referring to linguistic policies, which differ from one province to another, and to the society’s cultural characteristics. Though they are adapted to each province, the questions are designed to measure the same phenomena - an attitude, for example - but the attitude is sometimes expressed towards social features that are somewhat different. We have chosen to make this comparison based on the scores obtained for factors made up of several items rather than comparing results on isolated questions. This leads to comparisons in which we must take into account that some factors are comprised of different items from one province to another. It will be mentioned where this is the case.

We also have factors whose composition varies across the provinces even though the questions are exactly the same. Such a situation occurs when, among a list of similar questions, those that make up the factor are not the same from one province to another. This leads to highly interesting results, most notably with respect to two factors: civic identity and participation.

The factors upon which the comparison is based can be brought down to three broad dimensions: Identity, Agreement with equality and Participation, in accordance with the general conceptual framework that guided us in the

2 preparation of the questionnaire. The comparison will thus be presented by dimension.

Conceptual Framework and Variables

.

Identity Dimension

Figure 1. Identity dimension

The identity dimension is made up of two main factors: civic identities and differentiating identities. We have also added to this dimension the attitude towards linguistic diversity, which presents remarkable co-variations with the identity factors.

The most striking general result to emerge is that the cluster analysis for each province has differentiated types of citizens who are quite different from one another with respect to some, but not all, factors. Thus, we obtained four types for Quebec, where we have twice aggregated two profiles; four types for New Brunswick, where we aggregate two profiles, and five types for Alberta, which exactly correspond to the five types distinguished through the cluster analysis.

Each type is represented by a different colour in the diagrams. A deviation of one scale point, which corresponds to one half of the standard deviation, represents a significant difference (cf. Torney-Purta 2002 ). In this presentation, we will mostly take into account the differences that score more than one point on the ten-point scale.

As we will be able to observe throughout the presentation of our results, types are highly contrasted on many factors in the three provinces. We therefore believe we were justified in our decision to analyse the data by sub-classes.

Comparison on identity factors.

For Quebec, we can observe that one type (blue column) presents a high average on all factors of the identity dimension, while another type (yellow column) scores low on all factors. The latter will be designated as individualists.

3

The two types represented respectively by the green column and the red column feature contrasting scores from one factor to another. One of these

(green) represents a high level of identification to Canada and a low level of identification to Quebec. The other (red) presents the opposite profile: a high level of identification to Quebec and a weak level of identification to

Canada. Even among these two types, both poles of civic identity are not antagonistic; rather, we find an order of precedence between the two. Both of these types do not distinguish themselves in their level of identification to a particular group.

Interesting similarities and differences between the three provinces come to light when we include the diagrams representing New-Brunswickers and

Albertans. In New Brunswick and Alberta, there is no separate factor of identification to the provincial community. The civic identity of young citizens in these two provinces is entirely expressed in a single factor that amalgamates Canadian and provincial identities.

In New Brunswick and Alberta, we find the same type represented by the blue column, which presents high scores for all factors in New Brunswick and in Alberta.

We can identify two individualistic types in Alberta, both featuring weak levels of identification to the civic community and to their differentiating community (orange and yellow columns). We find the same type (yellow column) in New Brunswick, representing respondents who demonstrate a weaker sense of identification than others to the communities to which they belong (orange column).

Thus, one of the interesting general results so far is the emergence of two similar types that appear in all three provinces. One is individualistic, while the other strongly identifies with the communities to which it belongs.

The composition of the factors measuring civic identity in the three provinces presents an interesting contrast. In New Brunswick, the only items saturating this factor measure collective self-esteem. In Quebec, the feeling of resemblance to the other members of the community adds itself to collective self-esteem. In Alberta, the items measure social resemblance and proximity, but no item measuring collective self-esteem is included in the factor.

4

Attitude towards linguistic diversity.

In Quebec, one type very strongly distinguishes itself from the others through a rather very low positive attitude towards the use of languages other than French in the public sphere. A high concentration of francophones are to be found in this type and a high concentration of Anglophones are to be found in the other types much more favourable to the public use of another language than French.

In New Brunswick, two types present a less positive attitude toward that province’s bilingualism policy. They account for 60% of the anglophones comprised in the sample. Two thirds of francophones can be found in the two other types that present a favourable attitude towards bilingualism. It thus becomes apparent that the members of linguistic minorities in Quebec and New Brunswick are predominantly in favour of policies that protect the public use of their languages. And vice-versa.

In Alberta, types are highly contrasted in their attitude towards the use of languages other than English. Two types demonstrate tolerance in this regard, while the three others express their agreement with the official language policy of that province by a very low positive attitude towards the use of other languages than English.

Thus, in all three provinces, linguistic policies appear to be a controversial subject that divides citizens, a little less so in New Brunswick than in the other two provinces.

Equality dimension.

Figure 2. Equality Dimension.

For the equality dimension, four factors emerged from the confirmatory factorial analysis: (1) the inclusion of cultural diversity in the respondents’ perception of the provincial society’s collective identity; (2) the attractiveness of relations with people different from oneself; (3) the attitude towards reasonable accommodations; and, (4) the attitude towards the presence of persons of varied cultural identities in the public sphere.

5

We will first pay attention to the general level of agreement with the standards of equality and equity applied to all citizens regardless of their differentiating cultural identities. The comparison in this regard reveals that the levels of agreement expressed in Quebec and in New Brunswick are closely similar. In the two provinces, the level of response falls rarely below mid-scale and it reaches the 7/10 level in the same number of cases. The only contrast between these two provinces and Alberta is the greater number of types which scores under de mid-scale in Alberta. Overall, the contrast is small between the three provinces.

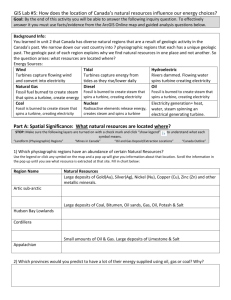

Of the three provinces, New-Brunswick is the one that attracts the least immigrants and includes the smallest population of Neo-Canadians. Indeed, while the general percentage of immigrant population in Canada is 17,4%, this percentage reaches 15,2% in Alberta, 9,4% in Quebec and 3,3% in New

Brunswick, which ranks second to last among Canadian provinces. (Data published by Statistics Canada based on the 1996 Census). The rate of immigrant population in the province does not appear to be a factor which affects the scores on that particular dimension.

As was the case with the identity dimension, we identify in all three provinces a type characterised by the highest, or among the highest, levels of response for all four factors. The type represented by the blue column, which featured the highest level of identification to both the civic and differentiating communities, reveals itself here again as the most clearly pluralistic in its relation to cultural diversity.

If we leave aside this exceptional type and concentrate on the other types, we notice that the highest contrast in Alberta and Quebec occurs in relation to the accommodation factor. This point warrants further discussion, and we will get back to it later. For the remaining three factors, the contrasts between types are not very significant in New Brunswick and Quebec since they very rarely exceed one scale-point.

What can we conclude from this finding? In both New Brunswick and

Quebec, where types are clearly differentiated by their socio-demographic composition, this variable does not seem to be associated to differences between types as regards their relation to cultural diversity.

6

In Alberta, the profiles are not differentiated by their socio-demographic composition. We find that one of the two individualistic types reveals a much less diversified representation of the collective identity than the others; it should be noted that, in this province as well, the scores barely reach the middle of the scale on that factor. For the Attraction factor, the strongest contrast occurs between the two individualistic types; this is also the case for the Presence factor. This brings to light the fact that, in Alberta, the highest contrasts occur between individualistic types that are identical in both their socio-demographic composition and their identity profile. We can therefore distinguish psychological types that strongly diverge from one another in their relation to diversity.

At this point, the Accommodation factor warrants further discussion. This factor presents a strong contrast between types mainly in Quebec and

Alberta. In Quebec, two types express a less positive attitude than the others.

Conversely, two other types demonstrate a more positive attitude. In Alberta, we have observed a sharp contrast between two types that score very low and three others that score significantly higher. Both of these provinces have been embroiled in intense public debates over cases of accommodation: we all remember the Albertan debate concerning the use of the Sikh turban by members of the RCMP and the wearing of such headgear in the halls of the

Canadian Legion; while in Quebec, the wearing of the hijab in one school and the bearing of the Sikh kirpan in another have sparked heated public debates. Nothing of the sort has occurred in New Brunswick, and therefore, it comes as no surprise that the subject of accommodation seems not a very controversial issue in that province. Indeed, the controversy has unfolded in the other two provinces whose histories have been marked by crucial events surrounding the opening up of public standards to religious diversity. For this reason, it is not surprising to find a similarity between Quebec and

Alberta in this respect. In spite of the differences between the youths of these two provinces, we find similar levels of contrast in their positions regarding accommodation.

It is interesting to note that the types in Quebec and Alberta with the least positive attitudes towards accommodations also score higher on the Presence factor. What hypothesis can be inferred from such a finding? These young citizens have positive attitudes towards the presence of a significant number of individuals of diverse cultural identities in the social sphere and the public sphere. They can accept the place occupied by cultural diversity where this

7 does not involve exceptional measures that modify the traditional standards of public institutions.

Participation dimension.

Figure 3. Participation Dimension.

The participation dimension includes four factors. Current participation points to political or civic participation behaviours over the last twelve months both inside and outside of the place of study. Future participation is a factor that measures the declared intention of investing oneself in political and community activities, opinion and interest groups and charity work in the coming years. Trust in political figures measures to what extent respondents believe that serving the public interest is the main concern of elected officials. Finally, the fourth factor measures the respondents’ estimation of the degree to which citizen investment in participation can effectively contribute to obtaining the results he seeks or desires.

In this dimension, we find once again the consistency of the type represented by the blue column in providing the highest levels of response for all factors in all three provinces.

From a general point of view, we can observe that contrasts between types rarely exceed one scale-point in this participative dimension. Very often, the levels of response fall quite clearly below the middle of the scale. The only contrasts worth considering are those that occur in the comparison of individualists (yellow column) and the most participative respondents, represented by the blue column. The other types always fall somewhere between the two.

Of major interest is the rather surprising result obtained on the level of response to current participation in New Brunswick, which is quite high for both types, while the scores for current participation barely exceed 4/10 in the other provinces. In New Brunswick, this factor is made up of only five items, whereas it includes thirteen items in Quebec. In Alberta, the current participation factor includes six items that are very similar to those making up the factor in New Brunswick. We therefore find differences in the composition of the factors that must be taken into account in our comparisons.

8

Four items which make up the factor in New Brunswick and Alberta refer to participation at the place of study. The measure of out-of-school community involvement completes this factor. The very high level of response of the two types in New Brunswick thus mainly indicates a strong participation in student activities at the place of study, which may involve many activities related to the social student life and student cultural activities. Current participation in Alberta is of the same nature, although not as strong, which could indicate a lesser importance of social life at the place of study.

In Quebec the current participation factor is saturated with items that, considered as a whole, indicate involvement in the areas of political, community and social life. A high score on this factor would indicate a very strong involvement in society and politics as well as at the place of study.

Consequently, the level of response observed, which is clearly below the middle of the scale, must be interpreted as a low level of participative investment in a wide range of activities of political and civic participation.

The same holds true for the declared intentions concerning future participation, where most of the types are consistent in their response level.

However, a few do express the intention of making a greater investment in the future than at the present time. Here again, we must take into account the fact that, in Quebec and Alberta, the level of response covers a wide range of activities of political and civic participation. As regards political participation, this relates to a highly active involvement in political life, such as joining a political party, working for elections, and contacting politicians to express one’s opinions. The levels of response to the factor of future political participation therefore indicate a very active involvement in political and civic life. The results obtained must be interpreted with this in mind. It expresses the fact that youths in all three provinces intend to occasionally invest themselves in a wide array of activities representing a high level of political and civic participation.

It should be noted that voting in elections is not included in these factors because the level of response to this item is generally quite high and this level varies very little across all the samples. Even though it is excluded from the Participation factor, this type of response indicates that the intention to vote in elections is very widespread among these youths. The interpretation of this level of response must nevertheless take into account the data pertaining to the actual level of voting participation among youths between 18 and 24 years of age. A recent survey (Léger Marketing) reveals

9 that only 28% of young Canadians within this age group exercise their right to vote (La Presse, June 10 th 2002).

As can easily be observed, the level of trust towards elected officials scores below the middle of the scale and the various types are not differentiated by this factor. Young citizens appear to share a feeling that is apparently generalised throughout the population, as it is revealed by public opinion polls where very low percentages of respondents express trust towards political figures.

On the other hand, as regards the Efficiency of Participation factor, apart from the individualistic type that tends to score lower than the others in all three provinces, there is no differentiation between types. It should nevertheless be noted that the highest levels of response in the Participation dimension occur for this factor. This is quite obvious in Alberta, and a little less so in New Brunswick. The level of response for this factor in Quebec is not particularly remarkable. However, the difference between the levels of response to the Efficiency factor and to the Current and Future Participation factors is not an indication that, on the one hand, one’s think that participation can lead to changes but, on the other hand, that one’s would prefer not to get involved. Such an interpretation is ruled out by a mid-level positive correlation (,42) found in Quebec between the Efficiency factor and the Current and Future Participation factors throughout the sample. The same is true for New Brunswick. The most participative respondents are also those who give the highest scores for Efficiency of participation.