Bycatch: Interactional Expertise, Dolphins and

advertisement

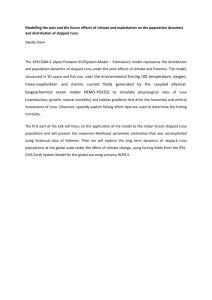

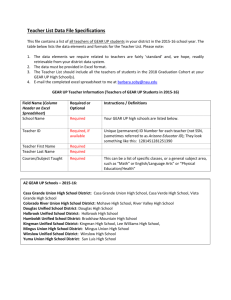

Bycatch: Interactional Expertise, Dolphins and the U.S. Tuna Fishery Lekelia Jenkins1 632 34th Street, Richmond, CA 94805 USA LDJ@DUKE.EDU Abstract The burgeoning field of studies in expertise and experience (SEE) is a useful theoretical approach to complex problems. In light of SEE, examination of the controversial and wellknown case study of dolphin bycatch in the U.S. tuna fishery, reveals that effective problemsolving was hindered by institutional tensions in respect of decision-making authority and difficulties with the integration of different expertises. Comparing the profiles of four individuals, who played distinct roles in the problem-solving process, I show that (1) to address a complex problem, a suite of contributory expertises—rarely found in one individual—may be required; (2) formal credentials are not a reliable indicator of who possesses these necessary expertises; (3) interactional expertise and interactive ability are useful tools in combining the contributory expertises of others to yield a desirable collective outcome; and (4) the concepts of contributory expertise and no expertise are useful tools for understanding the actual contribution of various parties to the problem-solving process. Keywords: Expertise and experience, bycatch, tuna-dolphin, invention, conservation technology, interactional expertise 1 I would like to acknowledge my PhD advisors Larry Crowder and Michael Orbach for their advice and support over the course of my dissertation research at Duke University. I am thankful to Michael Gorman and Sara Maxwell their insightful input. I greatly appreciate Harry Collins for his extensive editing and advice. I would also like to thank the National Science Foundation and the Oak Foundation for funding this research. 1. Introduction In 1963 the feature film “Flipper” and the subsequent television show, which aired from 1964 to 1967, sparked a national-wide craze in the U.S. for dolphins and other marine mammals. The public came to view marine mammals—more so than many other animals—as uniquely intelligent, caring, and lovable. In the late 1960s the first reports of the large dolphin mortality by the tuna fishery began to surface in the media. By 1971, articles in Newsweek and Life magazines firmly placed the tuna-dolphin issue on the national platform.2 The public with its newfound love for marine mammals was outraged. People from all walks of life, from scientists and environmentalists to housewives and school children, bombarded their congressmen with letters decrying the slaughter of dolphin and demanding protective action. In 1972 Congress drafted and passed the Marine Mammal Protection Act (MMPA) and in 1973 the Endangered Species Act. The MMPA not only protects marine mammals that are endangered, but all marine mammals, and mandates that their populations be as large as healthily possible. One outcome of this legislation was a new effort to prevent the accidental killing of dolphins during tuna fishing, a problem known as `bycatch.3 I report a case study of the way fishers and researchers used different kinds of expertise in their joint attempts to reduce bycatch. I begin with a description of the technique of tuna fishing and the institutional tensions between government agencies and fishers as they tried to solve the problem. I then discuss the methodology of the study, its results, and the way they bear on the theory of expertise. In order to analyze both the collaborative process and the problems faced by individuals, I will look at the career and work of some of those who were acclaimed by their peers to be the best among them in their different roles. These individuals are William Perrin, NMFS biologist; Harold Medina, tuna fisher; Dick McNeely, gear specialist; and James Coe, fishery observer turned gear technician. The experience of these individuals shows us that formal training and qualifications are not the key to attaining high levels of expertise and— 2 On this, see Anonymous (1971a) 3 Bycatch is the incidental harming or death of non-target organisms as a result of interactions with fishing gear. Medina aside—they also show us that cooperation facilitated by interactional expertise is the norm when such a complex set of goals have to be met.4 2. Developments in tuna fishing and the bycatch problem Tuna fishing in the U.S. was largely based in San Diego. The early 1960s saw the introduction of a new fishing technique, poles being replaced by nets called a `purse seines.’ The hundred or so boats fishing the Eastern Tropical Pacific quickly became the second most profitable fishery in the country. In 1964, however, a tuna fisher alerted California wildlife managers about the numbers of dolphins being accidentally killed in purse seines.5 Subsequent estimates suggested that several hundred thousand dolphins were being killed each year. 6 In 1969, the U.S. Bureau of Commercial Fisheries (BCF)—which soon became part of the newly established National Marine Fisheries Service (NMFS)— began a research project to investigate the problem. The primary activity of the project was to use fishery observers to collect biological and ecological data. The purse seining process involved encircling tuna that are either swimming as a free school, as a school associated with floating debris or as a school associated with dolphins. 7 An airplane, or a fisher positioned in the crow’s nest using high-powered binoculars, searched for signs of tuna. These signs included birds, whales, dolphins, floating debris, certain water disturbances, and certain displays of shadows and reflected light. If the captain was satisfied that 4 Interactional expertise is a level of expertise that allows a person to interact productively with other experts if not do the jobs they do – which demands `contributory expertise.’ The person with interactional expertise can understand and us the technical language. Collins and Evans (2002), Collins and Evans (2004) and Collins and Evans (2007). 5 At the time of the case study, dolphins were often referred to as porpoises. 6 For more information on the levels of dolphin mortality in the tuna fishery see NRC 7 To learn more about the tuna purse seining process read Orbach (1977) and McNeely (1992). (1961). these signs do represent the presence of tuna, he ordered a `set’. 8 If the tuna were associated with dolphins, the fishers used speedboats to chase and herd the dolphins, bunching them so that they were easily surrounded. The `seine skiff’ towed the seine net, which was approximately a mile in length, around the school until it was encircled. Fishers then secured the tow-line to the tuna boat, or `seiner.’ The net then floated in the water forming a large cylinder. Next, fishers pursed (gathered in) the bottom of the net, making it bowl-shaped. Then, fishers pulled the purse rings and the bottom of the net aboard the seiner. The fishers fed the end of the net through the powerblock in order to draw the net onboard the boat. This “drying up” process greatly reduced the circumference of the net, thus herding the fish into a small space. The fishers then `brailed’ the tuna onboard with a large scoop. Once the tuna are aboard, the fishers quickly preserved them by freezing them in refrigerated holds. `Fishing on dolphins’ soon became the most popular method of tuna fishing, because it yields large yellowfin tuna, which were the size and species preferred by tuna processors, and because dolphins, which are frequently on the surface, were a good visual indicator of tuna. Unfortunately, this tuna fishing method can result in significant dolphin mortality. Recall the purse-seining process; as the diameter of the net was decreased, the dolphins became bunched together in a small area. Even though dolphins are capable of jumping several feet above the water surface, when enclosed in a net they failed to do so and instead became passive. Thus, the dolphin rarely attempted to escape, rather they huddled together at the surface or lay submerged against the bottom of net. Frequently, the dolphins would come in contact with the net and became entangled in it. Unable to surface to breathe, they drowned. In addition, some were crushed by going through the powerblock, some injured falling from the net onto the deck, and some were fatally maimed when fishers tried to remove them from the net.9 Adverse net dynamics can cause “disaster sets” also referred to as “problem sets” in which most or even all the encircled dolphins were killed. Disaster sets occurred when shifting currents and gear malfunctions destabilized the net causing it to bulge, slacken or even collapse. 8 The term set refers to the placing of the net in the water to catch fish. 9 For more information on the causes of dolphin mortality in the tuna purse seine fishery see NRC (1992). When these net distortions occurred, dolphins could become enfolded in portions of the net, trapping and drowning them. The MMPA drove both government and industry to solve the dolphin bycatch problem. With the passage of the Act, the NMFS was required by law to reduce dolphin bycatch. Its responsibilities in the dolphin conservation program were to develop tuna fishing regulations, enforce regulations, conduct extension activities, as well as perform basic biological, conservation and gear research. Industry felt compelled to solve the bycatch problem, because it feared the complete closure of the tuna fishery if dolphin mortality was not reduced. To achieve their common goals government and industry needed to work together. NMFS required the fishing knowledge and experience of the industry and industry required the financial and scientific support of NMFS. Unfortunately, several points of contention made it difficult for them to coordinate their actions. Concerned about negative media coverage and potential lawsuits from environmentalists, NMFS was secretive about its tuna-dolphin research. This lack of transparency led many fishers to question whether or not NMFS—which had always been an advocate of fishery development—was truly committed to the continuance of the tuna fishery. Many NMFS personnel, on the other hand, believed that the majority of tuna fishers were not committed to fully addressing the dolphin bycatch problem. Distrust of each others motives created an unstable foundation on which to build collaborative projects. Furthermore, there was a fundamental cultural difference in how NMFS and the tuna industry determined rights to decision making authority. As one senior participant put it “NMFS didn’t listen to fishermen.” In this, the study is reminiscent of Wynne’s account of the expertise of the Cumbrian sheep farmers following the Chernobyl disaster. There too, expertise unsupported by scientific credentials appears to have been given less weight than it should have been given.10 NMFS treated academic credentials as the appropriate warrant for authority and decision-making power. Whereas, tuna fishers relied on superior fishing skills gained from experience at sea. Captains, who have almost monarchial authority while at sea, were now subject to the decisions of young NMFS staffers with little commercial fishing experience. 10 For more on this see Wynne (1989) In September 1971, 2 years after the beginning of the joint program, attempts were being made to improve the troubled NMFS/industry relationship. A cooperative research program between the representatives of NMFS and industry agreed: (1) there would be twenty operational trips on tuna boats with observers to record dolphin behavior and efficiency of gear modifications; (2) industry would make available sixty ship days in 1972 to conduct basic research on population dynamics and behavioral patterns of dolphins; and (3) industry would provide specimens of dolphins killed during fishing.11 This lopsided agreement illustrates the lack of parity between government and industry in the invention and development process. Clearly NMFS viewed industry’s primary role as providing the vessels and specimens that NMFS needed to achieve its research objectives. Industry, however, had research objectives of its own. For instance, the American Tunaboat Association (ATA) provided some vessels, most of which had Medina panels (see below), with datasheets to record, among other data, the number of dolphins captured and killed. This shows that the ATA was independently trying to evaluate conservation technologies in addition to its cooperative efforts with NMFS. The root of the cooperation problem was not lack of good-will, but rather perceptions of the nature of expertise and associated rights to authority. While NMFS earnestly sought industry’s cooperation in innovative fishing gear research to save dolphins, it did not see fit to involve industry in developing the overall research plan. Specifically, the Tuna Porpoise Review Committee encouraged the gear research subcommittee “to interface closely with industry, soliciting views, etc.”12 While there were government personnel and academics on the Tuna Porpoise Review Committee there were no industry representatives. The directives of the Committee show the good intentions of NMFS to work with industry to solve this problem. But, the Committee’s composition serves to highlight the dichotomy between how NMFS viewed the value of industry’s knowledge and industry’s right to hold authority in the invention process. This remained an issue throughout the gear research program. Industry thought the right to be involved in the decision-making process should be based on experience and expertise evidenced 11 From the government report NMFS (1971), which is available from NOAA Fisheries Southwest Fishery Science Center. 12 Quote taken from Alverson (1972), which is available from NOAA Fisheries Southwest Fishery Science Center. by innovative, skillful, and successful use of fishing gear while NMFS looked to credentials, formal education and academic degrees. These differing values exhibited at the institutional level also led to tension on the ground – or should we say `on the sea’ – when it came to developing dolphin conservation technology. The conflict at both levels yields useful insights into the Theory of Expertise.13 3. Methods I examined the tuna-dolphin problem and the surrounding activities between 1964 and 1981. The year 1964 was when dolphin bycatch was first brought to the government’s attention while 1981 was the last year that a dolphin conservation technology development program existed within NMFS. Most of the major developments in dolphin conservation technology for the tuna industry occurred before 1981. The burden of this analysis is the way interactional expertise is used to bridge the gulf between the hands-on experience of contributory expertise and knowledge without experience.14 It is well known that hands-on experience and other kinds of knowledge are very different. The gap was brought forcibly to my attention during an earlier study related to the fishing industry. While conducting an ethnographic study of the testing of turtle conservation technology for the shrimp fishery, I underwent instruction in the basics of net construction. I tried to learn to sew nets together and splice rope for the modification of shrimp trawls. Shrimp trawl design is much simpler than the tuna purse seines discussed here and I hoped that my years of recreational fishing, crafting, and knitting would help – but it did not. After a morning of direct tutelage with persistent questions and false starts, I was able to perform a poor mockery of the elegant work of my instructor. Examining my product and its twisted loops, slack knots, and uneven stitches, my 13 The technical terms, `interactional expertise’ and `contributory expertise’ used in this paper are taken from Collins and Evans (2002) The term `interactive ability’ is taken from their `Periodic Table of Expertises’ Collins and Evans (2004), reproduced in their Rethinking Expertise, Collins and Evans (2007). 14 Contributory expertise ” is enough expertise to add to the science of the field being analyzed Collins and Evans (2002), Collins and Evans (2004) and Collins and Evans (2007). instructor promptly unraveled the work and, in minutes, redid with skillful ease what had taken me an hour to complete. My instructor told me how he had learned his net-making skills. He had learned from his father who was a fisher. Unlike my focused instruction, his father and the other fishers refused to answer direct questions or give direct lessons. Rather he had to learn from years of observing. Over time I tried his learning method of observation. After nearly a week of watching gear specialists modify nets, my intellectual knowledge of the process increased, but my skill, if any thing, had decreased. It became clear to me that true skill in net building would take years of hands-on experience to acquire. A workshop, even under the watchful eye of a net specialist would not suffice for imparting contributory expertise. The shrimp study put me in a good position to understand different kinds of experience in the fishing industry but in the main I gathered data for this study by examining inventions, conducting interviews, and analyzing documents.15 I conducted 16, on-site, semi-structured and unstructured personal interviews with key informants.16 These interviews mostly occurred during two, two-week long trips in November 2003 and January 2004. The sample population consisted of representatives from stakeholder groups, including international and federal policy-makers and managers, scientists, inventors, as well as industry and environmental organization representatives. I initially established a sample frame using a purposive sample of prominent 15 Because of poor-record keeping and the deaths of several of the key players in this case study, it was not possible to obtain saturation for most of the code topics. Another confounding factor was that a disproportionately large number of the surviving documents were authored by NMFS. Because there were few or no documents available from other stakeholders for many topics, the possibility exists that the case study is skewed towards NMFS perceptions. However, of the industry’s, conservation community’s, and other’s documents available, these—as well as my interviews—corroborate the tuna-dolphin controversy as portrayed in the case study. For this reason, I firmly believe that the analysis of the tuna-dolphin case study offered herein is an accurate assessment of the situation. 16 The study considers individuals as representatives of organizations; verbal and written statements are taken to be valid representations of the opinions, attitudes, and beliefs that guided the work of those organizations. individuals frequently mentioned in the literature pertaining to the study. 17 The purposive sample led to a snowball sample: informants were asked to name other individuals who were knowledgeable about the case study and many of these were then interviewed.18 To place informants at ease while discussing this controversial case, I took extensive notes but did not record the interviews. Thus, where indicated, some quotations are really close paraphrases based on these notes. I also collected hundreds of documents, including government reports, research records, workshop reports, panel reports, memos, personal letters, and educational videos and pamphlets from the key informants’ personal archives. I analyzed the text of the interviews and documents in the spirit of Grounded Theory allowing theories to grow out of categories and concepts that initially emerged from the analysis of the texts of documents and interviews.19 4. The case study In 1972, with the passage of the MMPA looming, and plans taking shape to infuse $250,000 into the dolphin bycatch reduction research program, NMFS set up a committee to decide on the appropriate course of action. The committee found that the most promising course of action would be a vigorous program of research on new technical gear designed to aid dolphin conservation. This conclusion was also supported by the tuna fishing industry. What knowledge and skills would be needed to accomplish this research? Several of my key informants cited mechanical engineering as an essential expertise: the inventor of a conservation technology must have the skill to design and build the device. According to William Perrin, the head of the gear research program from 1970-73: 17 To learn more about the socio-economic, policy, or other aspects of this case study, please see Coe (1984), Joseph (1994), Joseph and Greenough (1979), NRC (1992) and Orbach (1977). 18 For more on this, see Bernard (2002). 19 For a detailed discussion of Grounded Theory read Strauss (1998). Expertise in tuna fishing lies in the industry, not in NMFS. Scientists can do basic behavioral work to find out what makes a porpoise tick and can do the necessary population studies to assess the impact of mortality in the fishery, but actual development of improved fishing gear and methods can only properly be done by tuna-fishermen.20 So expertise in fishing gear and procedures is necessary, but must be supported by expertise in animal behavior and biology.21 The inventor of conservation technology must understand the workings of the fishing technology, so that the two can function in harmony. Furthermore, the fishing technology must continue to work while the conservation technology protects non-target organisms. In order to achieve this, the inventor needs to understand the biology and behavior of both fish and protected species. The expertises needed for a successful gear research program are, then, `contributory expertises’ in animal behavior and biology, mechanical engineering, and fishing gear and procedures. The position of a putative, full-blown, gear expert is illustrated in Figure 1. 20 This quote is taken from Perrin (1971c), which is available from NOAA Fisheries Southwest Fishery Science Center. 21 For simplicity, the term biology will also be used to encompass animal ecology, anatomy, and physiology. Animal Behavior & Biology Gear Expert Fishing Gear & Procedures Marine Engineering Figure 1: Basic Knowledge Needed to Invent Dolphin Conservation Technology On the other hand, the roles actually filled in the gear invention process at the outset of the project are largely those set out in Table 1, below. Fishers’ primary duties were to run the boat and catch tuna. Scientists collected and analyzed data. `New hires’ were graduates in biology recruited specially for the project to be trained to serve as fishery observers. Fishery observers were former new hires who have completed training in data collection and were gaining experience in fishing gear and procedures while serving on boats. And, gear technicians were like observers who know more about fishing gear and fishing procedures. In the almost complete absence of individuals who could do everything, the collective role of gear expert had to be fashioned from this set of partial expertises. At the same time, individuals tried to come to grips with each others’ technical worlds so as best to fit in with the overall project. I will now profile four exemplary individuals, who participated in the invention process in different roles. These profiles will reveal the factors associated with successful collaboration and invention of dolphin conservation technologies as well as describe how these collaborations embodied the all the necessary contributory expertise. As we will see, Medina was, perhaps, the one `exception that proves the rule’ in that he seemed to fulfill the full definition of gear expert. Position Fisher Expertise Contributory: fishing gear & procedures Scientist Contributory: animal behavior & biology New Hire Interactional: animal biology Interactional: fishing procedures Fishery Observer Duties Operate and maintain the boat & gear Catch tuna Invent new conservation technology and improve existing ones Collect and analysis data on the behavior & biology of tuna & dolphins Invent new conservation technology and improve existing ones Train to be a fishery observer Gear Technician Contributory: animal behavior & biology Interactional: marine engineering Fishing gear Collect data on tuna catch and dolphin bycatch Collect data on the behavior & biology of tuna & dolphins Training Years apprenticing under expert fishers Six to eleven years of specialized biological education Four year college degree in Biology That of a new hire Several weeks long workshop on dolphin & tuna biology and data collection methods That of a fishery observer Lessons on net construction & repair Apprenticing under expert fishers Perform the duties of a fishery observer Collect and analysis data on the performance of Contributory: prototype gear fishing procedures Invent new conservation animal behavior & technology and improve biology existing ones Table 1: The expertise and roles of various players in the gear development process 4.1 William Perrin, NMFS biologist Perrin began working for NMFS in 196?. From 1969-1973, he served as head of the gear research program. Developed in 1970, his most important invention was the porpoise rescue gate. Perrin began his career at NMFS as a doctoral student employed by NMFS to study dolphins. As a scientist, especially as head of the research program, Perrin had two principal duties: (1) collect and analyse data on the behavior and biology of dolphins as well as tuna; (2) invent new conservation technology and improve existing ones. The frequency of citation of Perrin’s earlier papers and his admirable reputation as a premier marine mammalogist (built on the foundation of his early dolphin work), attest that at the time of the case study Perrin had contributory expertise in dolphin behavior and biology (see Table 2). This contributory expertise was definitely sufficient for performing the first duty as concerns dolphins. However, this is only one component of the assemblage of expertise needed for inventing conservation technology. Examining Perrin’s efforts at invention will reveal his level of expertise in the other areas as they stood at the time. INDIVIDUAL Perrin Medina McNeely Coe Animal Biology Contributory Contributory Interactional Contributory Animal Behavior Contributory Contributory Interactional Contributory EXPERTISES Fishing Gear Interactional Contributory Contributory Interactional Fishing Procedures Interactional Contributory Contributory Contributory Mechanical Engineering None Contributory Contributory None Table 2: Levels of expertise possessed by profiled individuals The most promising prototype Perrin produced was the porpoise rescue gate.22 The original plans for this device called for a four-fathom long section of the corkline to be replaced 22 Perrin had the assistance of animal behaviorists, fishers, and other NMFS staff in developing the porpoise rescue gate; however, the original idea and final decision for with several inflatable sections.23 A system of independent air conduits would lead to a single connector at the end of the inflatable section. A skiff equipped with a gasoline-powered vacuum pump and compressed air tanks would connect to the air system after the net was set and remain stationed at the gate during the rescue operation. The gate would be opened by deflating the corkline and raised by rapid injection of air from the tanks. The operative concept was that the dolphin would recognize the deflated corkline as a break in the net and swim through the opening to safety. Perrin realized that an essential property of the gate was that it must be possible to raise the gate in one or two seconds in order to prevent tuna loss.24 Thus Perrin understood the behavior of tuna and applied this knowledge to the creation of the gate, indicating that he had contributory expertise in tuna behavior as it bore on the problem of fishing bycatch. During the course of conducting field research onboard tuna seiners for his doctoral work, Perrin acquired interactional expertise in fishing gear and procedures (Table 2). However, as illustrated by the previous quote from Perrin, he was aware that the NMFS scientists—himself included—lacked contributory expertise in fishing gear and procedures.25 His assessment is supported by evaluations of the porpoise rescue gate by the fishing industry representatives, whose comments often concerned the commercial practicality of the device. For example, one criticism was that there was too much heavy gear on the gate-tending skiff, which might cause it to capsize in rough weather.26 On industry’s suggestion, NMFS personnel modified the gate to modifications was his. Thus the invention will be discussed in terms of Perrin’s expertise. For details on this invention see Perrin (1970), which is available from the NOAA Fisheries Southwest Fishery Science Center. 23 Corkline is a rope with attached floats that suspends the net in the water column. 24 For more on this see Perrin (1970), which is available from NOAA Fisheries Southwest Fishery Science Center. 25 For more on this see Perrin (1971c), which is available from NOAA Fisheries Southwest Fishery Science Center. 26 For more on this see Perrin (1971a), which is available from NOAA Fisheries Southwest Fishery Science Center. allow operation from the deck of a tunaboat.27 Even though Perrin actively sought the expertise of tuna fishers and made the modifications they suggested, the porpoise rescue gate still remained problematic. The continued problems seem to have to do with mechanical engineering. During one evaluative meeting in 1970, Perrin stressed that the gear could be engineered to reduce weight and increase reliability. But notably, in a letter to NMFS, the President of Westgate Terminals, wrote, None of the masters or net men I have talked to can offer a practical method of installing, or operating in the open sea, a “gate” in the net such as described in the MS [manuscript]. The apparently desirable requirement for complete elimination of floats in the “gate” section of the cork line also presents a practical operating problem.28 Evidently, the mechanical problems were beyond the expertise of fishers with contributory expertise in fishing gear and would require the skills of a mechanical engineer. Perrin did not have a background in mechanical engineering (Table 2), so he was suggesting that others engage in the mechanical problem-solving. However a year later in 1971 a NMFS document stated “The gate…will need further engineering if it is to be used by commercial vessels.”29 The engineering work remained incomplete, because at that time there was no one working in the gear research program with contributory expertise in mechanical engineering. After this year there was no further work on the porpoise rescue gate, because the engineering problems proved too difficult to surmount. 27 For more on this see Perrin (1971b), which is available from NOAA Fisheries Southwest Fishery Science Center. 28 This quote is taken from Gehres (1971), which is available from NOAA Fisheries Southwest Fishery Science Center. Westgate Terminals is a major tuna processing company. A net man is a person (typically a fisher), whose has special skill is making and repairing fishing nets. 29 This quote is taken from Anonymous (1971b), which is available from NOAA Fisheries Southwest Fishery Science Center. As the above profile reveals Perrin was not—nor does he present himself to be—a gear expert. His knowledge and experience was not sufficient to invent dolphin conservation technology on his own. Nevertheless, as head of the dolphin conservation program it was his responsibility to make sure the task was fulfilled. Wisely, Perrin supplemented his contributory expertise in animal behavior and biology with the contributory expertise of tuna fishers in fishing gear and procedures. In my interview with him, Perrin said that he believed that the porpoise rescue gate was a viable idea and that he simply needed more time to develop it. However, more importantly I believe he needed on staff a person with contributory expertise in mechanical engineering, on which Perrin could have drawn. Also because Perrin did not have interactional expertise in mechanical engineering, in order to collaborate effectively with him this person would have needed interactional expertise in animal behavior and biology as well as fishing gear and procedures. Unfortunately, the right combination of expertises does not seem to have occurred. 4.2 Harold Medina, fisher Medina began tuna fishing in ???? and became Captain of his own boat in ???? Developed in 1971, his most important invention was the Medina Panel. Harold Medina grew up in a tuna fishing family. Because he didn’t perform well in school, he ended his formal education during high school. Medina then served as a merchant marine before becoming a commercial tuna fisher and eventually captain of his own boat. Gaining a reputation as a highliner, Medina was admired by his peers for his fishing skill.30 Medina’s life experience and reputation reveal that he had contributory expertise in fishing gear and procedures (Table 2). Medina spoke of his technological innovativeness and mechanical engineering abilities. He claimed to be the first tuna fisher to try sonar, the omega navigation system, and satellite navigation. He also asserted that he was responsible for increasing fishers’ safety by moving the 30 A highliner is a boat captain whose superior fishing skill yields major financial profit and a reputation as a master fisher. winch from the deck of the boat to the boom. He recounted that when he asked for this modification “the boatyard gave me a hard time but now all boats are this way [paraphrased].” In our interview he declared, “I can do anything with my hands….I can do anything on a boat.” He then listed his talents which including being a good carpenter, net man, engineer, and navigator. He knew how to overhaul boat engines as well as build and repair his own nets. These skills make it apparent that despite Medina’s lack of formal education he had contributory expertise in mechanical engineering (Table 2). Through his years on fishing boats Medina seems to have acquired contributory expertise in animal behavior and biology as concerns dolphins and tuna during the tuna fishing process. A typical NMFS scientist has a Masters degree or Ph.D. in Biology or related fields. These degrees represent six to eleven years of collegiate education (Table 1). Growing up in a fishing family and working onboard tuna boats, Medina’s direct experience observing tuna and dolphins exceeded the years of a scientist’s formal education. Medina’s experience amounted to an apprenticeship and self-taught education in the science of how tuna and dolphins interact with tuna fishing procedures. The litmus test of this and Medina’s other expertise is the success of his most effective dolphin conservation technology—the Medina panel. Medina observed that dolphins were frequently entangled in the net as they attempted to escape when their flippers and rostrums became snared in the mesh of the backdown channel. A backdown channel is a corridor of net that is formed while executing the backdown method. This is a dolphin rescue procedure, which involves reversing the boat so that part of the netting becomes submerged allowing the dolphins to escape to safety. It is the submerged area and the portion of the net leading to it that are referred to as the backdown channel. Medina surmised that using a smaller mesh-size for the netting in the backdown channel would prevent dolphins from becoming entangled. He conjectured that a two-inch mesh would provide maximum protection for the dolphins without creating adverse drag on the net and so reducing fishing efficiency. The result was a prototype consisting of a two-inch mesh panel of webbing seven hundred feet long and sixty feet deep that replaced the net’s large-mesh webbing in the backdown area of the net. When he presented his concept to NMFS in 1971, Medina claimed that while testing the prototype he had achieved zero dolphin mortality on some sets. The Medina panel in combination with the backdown method is widely accepted by the fishing industry, government, and dolphin conservation community as making the most significant contribution to reducing dolphin bycatch in the tuna fishery. After testing the device, NMFS promulgated a regulation in 1974 requiring its use throughout the tuna fishery. Many skippers had already begun to use the Medina panel, because of the increased fishing efficiency it offers. A NMFS memo stated that in 1972, 40-50% of the industry had voluntarily adopted the panel and by 1973, 60-70% of industry had adopted it.31 This rapid adoption was unparalleled among the other conservation technologies proposed to reduce dolphin bycatch and is a testament to the Medina panel’s effectiveness and commercially practicality. Medina’s device was successful, because he was able to apply to the dolphin bycatch problem contributory expertise in fishing gear and procedures, mechanical engineering, as well as dolphin and tuna behavior and biology. It would be incorrect to assume—as NMFS did in its collaboration with fishers— that this assemblage of skills would be common to any experienced fisher or even a highliner. A high level of mechanical aptitude, not necessarily shared by other skippers, was a necessary ingredient. August “Augie” Felando, the President of the American Tunaboat Association, affirmed this to me, stating, “The San Diego fleet was not too knowledgeable about the purse seine. To find a solution they needed to focus on the net and most didn’t understand net dynamics and how the net worked [paraphrased].” This is because the majority of the tuna fishery converted from using fishing poles to purse seining just ten years prior to the start of the gear research program. Since the industry-wide conversion, the gear had rapidly evolved and the fishery expanded. Thus, many of fishers were still learning the idiosyncrasies of the purse-seining gear and could not be considered gear experts. As a result, while the average fisher did have more expertise than most NMFS personnel, the majority of them did not have enough experience to solve the bycatch problem. Medina’s assemblage of expertise marks him as a gear expert (Fig. 1), proving that gear experts need not be gear specialists by trade. Furthermore, Medina acquired all of his expertise outside of a formal education system. Because he did not have any degrees, he probably would not have been hired had he applied to NMFS to be a fishery observer or gear technician. 31 These statistics are taken from Barham (1974a), which is available from NOAA Fisheries Southwest Fishery Science Center. Fortunately his status as a highliner served as an adequate credential for NMFS to give his idea serious consideration. Medina’s career supports the claim that knowledge and experience, not degrees and credentials, are the better means of determining a person’s inventive ability. 4.3 Richard McNeely, gear specialist McNeely began working at NMFS in 1955. From 1973-1977 he was head of the gear research program. His most important inventions and innovations included the anti-torque cable (1973), large volume net (1973), super apron (1976), and counter-balanced purse block (1977).32 Richard “Dick” McNeely, as one might say, `was born to be an engineer.’ Yet, he never earned an engineering degree due to the exigencies of World War II. Though he cobbled 32 Anti-torque cable is balanced to eliminate twisting almost entirely. The anti-torque cable was not a new invention, but McNeely’s application of it in purse-seines was an innovation. McNeely proposed the use of anti-torque cable to prevent roll-ups, a cause of dolphin mortality. A roll-up occurs when the purseline twists, sometimes catching the net and causing it to spool around the purseline. Retrieval of the net must stop until fishers untangle the roll-up. This effort takes time, increasing the dolphins’ exposure to the net and risk of becoming entangled. Meanwhile the net, stagnant in the water, is more likely to collapse due to the effects of wind and current. If the net were to collapse, the vast majority, if not all, of the dolphins would become entangled and drown. The large volume net was deeper, being made of seventeen strips of webbing, rather than the industry standard of ten strips. This modification reduced the probably of roll-ups and net pockets, because the degree of net folding is dependent on the ratio of length to depth. The super apron was a small-mesh webbing insert that formed an inclined net ramp in the backdown area of the net. McNeely designed it to eliminate loose canopies of webbing, prevent entanglement, and permit separation of tuna from dolphins. The counter-balanced purse block consisted of a standard purse block with counterbalancing weights to channel the purse cable through the true center of the purse block, eliminating cable twists caused by the block and thus reducing the occurrence of roll-ups. together a thorough education in engineering his lack of a degree would be a problem throughout his career. McNeely’s mechanical engineering knowledge and abilities were acquired through apprenticeships under his father and several other mentors. His formal mechanical education began with six years of machine shop courses in high school. After receiving the highest score of any applicant ever on a mechanical aptitude test, he was admitted to a technical school. He also received technical training in pilot’s school, in correspondence school, and during a brief stint as an electrical engineering major at the University of Miami. Collectively his training covered machinery, sheet metal, welding, electrical, metallurgy, building construction, drafting, blueprinting, aerodynamics, meteorology and combustion engines. While working for General Electric as a machinist, he earned a reputation as a problem solver, so the company made him a traveling consultant.33 From boyhood McNeely was an avid recreational fisher; indulging his life-long interest in the water, he eventually acquired a position with BCF in 1955. McNeely was able to apply his knowledge of aerodynamics to hydrodynamics and net dynamics, resulting in several major advances towards developing a commercially practical new kind of trawl. He continued this pattern of engineering innovation throughout his career; NMFS later identified fourteen of these innovations to be of major importance. His contributions indicate that his contributory expertise in mechanical engineering extended to marine mechanical engineering (Table 2). Examination of his dolphin conservation technology prototypes lends further evidence of his contributory expertise in this area. After he was brought from another NMFS center to head the dolphin conservation gear research program, McNeely—like Perrin and Medina— systematically identified causes of dolphin bycatch. However, his analysis focused on physical characteristics of the gear that cause bycatch rather than on dolphin behavior and biology. For example, as opposed to creating a means of escape (e.g. the porpoise rescue gate) that operated on behavior principles or reducing the ability of dolphins to entangle themselves (e.g. the Medina panel) that operated on biological principle, he strove to reduce the occurrence of disaster sets. McNeely’s most promising inventions and innovations all worked to reduce disaster sets by 33 The company presented him as an engineer and billed clients accordingly, but refused to pay him at the same rate as his colleagues because he did not have a college degree. stabilizing the net so as to prevent the development of folds and canopies, a problem suited to McNeely’s mechanical problem-solving abilities. McNeely, when he first joined the BCF, lacked knowledge about commercial fishing gear and processes. This was made evident when he took civil service examinations to qualify for a permanent position in the organisation. He passed the Electronic Scientists test with a score of 86, but failed the exam for Fishery Methods and Equipment Specialists with a score of 69. Although his official title became Electronic Scientist, he still performed the job of a gear specialist, allowing him to learn on the job. McNeely compensated for not having a background in commercial fishing by actively seeking opportunities to go out to sea on fishing boats. He also learned a lot from equipping a vessel used to sample living species—from marine mammals to bacteria—off the coast of Alaska. McNeely outfitted the research vessel with a large variety of fishing gear, as well as spare gear and repair supplies. For another research expedition he spent three-fifths of one year at sea, which is on par with the at-sea schedule of many fishers. He claims to have been on every type of fishing vessel on both coasts and to be the only government scientist with such wide experience of boats. Throughout his twenty-two-year career with NMFS, McNeely sailed on 9 different research vessels and 32 different commercial fishing vessels, many of them on repeated occasions. His at-sea experience included sailing on approximately 15 different tuna boats. In 1959 and 1960, during the early stages of the tuna fleet’s conversion from a pole fishery to a purse-seine fishery, McNeely researched and documented the change. He believes he was assigned this task because he was recognized as the only person in BCF to have extensive gear expertise. (BCF’s concern for degrees, may explain why most BCF personnel did not have extensive gear expertise. This expertise is most readily found among fishers, but the formal education of fishers generally stops with or before high school.) The result of McNeely’s work was a detailed article that was published in a popular fishing magazine.34 Reprints of the article quickly swept through the U.S. tuna fishing community and abroad, serving as a `how-to’ manual for converting pole fishing vessels into purse-seiners. The article is credited for helping revolutionize tuna fisheries worldwide. The editor of Pacific Fisherman, a prominent commercial fishing magazine, acclaimed it as “one of 34 See McNeely (1961). the most important and significant reports in its 58 years of publishing to the fishing industry.”35 This contribution to gear development in tuna purse-seining illustrates that McNeely had gained contributory expertise in fishing gear and procedures, despite having never been a commercial fisher (Table 2). The one area in which McNeely lacked contributory expertise was animal behavior and biology. McNeely had neither Perrin’s years of education nor Medina’s years of direct experience observing dolphins and tuna while fishing. However, McNeely was observant of animal ecology. He noted the change in the composition of fish populations as the water and pollution levels rose in his favorite fishing areas. He brought this same awareness to his work documenting the gear conversion of the tuna industry. Through reading and observing, McNeely learned about the biology and life history of tuna and dolphins. Citing this in his memoir as “one of the more interesting aspects” of his work, he went on to summarize feeding behaviors, migration patterns, and reproductive biology of these animals. Even though his studies of these activities were too brief to acquire the depth associated with contributory expertise, it is clear that his ability to understand and discuss animal behavior and biology amounted to interactional expertise. As a gear specialist and head of the dolphin conservation gear research program, McNeely needed to apply knowledge of animal behavior and biology to solving the dolphin bycatch problem. How did he do this if he did not have contributory expertise in this area? McNeely used his interactional expertise to engage people with contributory expertise. He had a reputation as a gregarious talker and harvester of ideas (interactive ability). When he took over the helm of the gear research program, he brought in new research partners within other governmental agencies and within industry. He worked with academics and fishers, bringing their knowledge to bear on the dolphin bycatch problem. When others describe him, his interactive abilities are often mentioned. His ability to communicate so effectively indicates that he had interactional expertise in all three essential areas shown in Figure 1, including animal behavior & biology. Using this interactional expertise, he served as a conduit through which the contributory expertise of others could be applied to solving the dolphin bycatch problem. 35 This quote is taken from McNeely (2002), which is available from Lekelia Jenkins. One significant result of this type of collaboration was the super apron, which operated on a behavioral principle that tuna tended to stay in the deeper sections of the net, while the dolphins tended to stay closer to the surface. The super apron formed a shallow dolphin escape route, into which the tuna rarely ventured because they preferred deeper waters. McNeely won many awards and on his retirement, in 1977, NMFS praised his work, writing, “The tuna industry, as well as the environmental community, are greatly indebted to Mr. McNeely for his perseverance and success in dealing with an extremely complex difficult, and challenging assignment.”36 4.4 James “Jim” Coe, gear technician Coe began working at NMFS in 1971. From 1977-1981 he was head of the gear research program. Conceived in 1975, his most important innovation was the use of a snorkel, mask, and raft. James Coe succeeded McNeely as head of the gear research program, but before this he was one of about twenty gear technicians hired by NMFS. Most of the gear technicians shared a similar background. In my interviews with three former gear technicians—including Coe—they all acknowledged that NMFS initially hired them to be fishery observers and that they had no gear or fishing experience. NMFS hired most of the fishery observers as recent college graduates with a B.S. in Biology.37 As recent graduates, they were affordable labor. Their biology background indicates that they had interactional expertise in animal biology and perhaps animal behavior as well. This interactional expertise was sufficient to allow quick training in their primary tasks -- to record information about tuna catch and dolphin bycatch -- as well as to collect biological samples while on commercial fishing trips (Table 1). Even though their primary responsibility was data collection, the work helped the observers gain contributory 36 This quote is taken from NMFS (1977), which is available from NOAA Fisheries Southwest Fishery Science Center. 37 For more on this see Department of Commerce (1974), which is available from NOAA Fisheries Southwest Fishery Science Center. expertise in animal biology and behavior (Table 2). This is evidenced by the fact that several of the observers co-authored papers or reports in conjunction with the government scientists. 38 As a byproduct of their close contact with fishers during month-long fishing trips, the observers’ also gained interactional expertise in fishing gear and procedures,. After a season or two as observers, some of these individuals became gear technicians. Their experience as gear technicians made them proficient fishers; to gain acceptance and establish a spirit of cooperation on the boats, the technicians would often assist the crew with their fishing duties. Every former gear technicians I spoke to recalled that skippers offered them crew positions on almost every fishing boat they worked upon. Their comments clearly reveal that the gear technicians gained enough skill to be offered an entry-level position as a general crew member (Table 3). However an offer of this sort does not necessarily mean that they possessed great skill. During my interview, Coe claimed he “could speak purse seining and work every station on the boat and a lot of guys working for me [when he was head of the gear research program] could do the same [paraphrased].” His assertion that he and others could “speak purse seining” indicates that gear technicians had interactional expertise in fishing gear and procedures. The statement that he could “work every station on the boat” appears to indicate that Coe also had contributory expertise in fishing gear and procedures. But it is unlikely that Coe acquired contributory expertise in every station. The duties of those onboard a tuna boat are listed in Table 3. Rather, I believe that statement simply speaks to the jack-of-all-trades role that any general crew member would be expected to fulfill. Keep in mind that Coe’s impressive statement, refers only to his fishing ability. The duty of the gear technician was not to become a commercial fisher, but to invent conservation technology. As pointed out when discussing the case of Medina, contributory expertise in fishing alone is not sufficient. 38 For examples see Coe and Sousa (1972) and Holt (1973), which are available from NOAA Fisheries Southwest Fishery Science Center. Crew Position Captain/Skipper Certified Master Number of Fishers in Position One Mate Chief Engineer one (held concurrent with another position often Captain) One One Assistant Engineer Deck Boss Optional One Mast Man Skiff Driver Optional One Speedboat Driver Cook four or five One General Deck Crew three or four Duties of Position Authority over all the activities on the boat while at sea Determines when and where to fish Maneuvers the boat during sets. Certified by U.S. Coast Guard for operation of a tuna boat Must be onboard for legal fishing controls the powerblock during sets Responsible for all mechanical, electric, hydraulic, and chemical systems Orchestrates tuna preservation Assist Chief Engineer in his duties Responsible for all work involving rigging, net, deck, and deck watch. Hauling in of the net Fish Brailing Skiff retrieval Net Preparation for sets Searches for signs of tuna Operates the skiff Maintains the skiff Might oversee brailing Operates Speedboats Prepares food Assists with minor deck chores (e.g. stacking the net rings, etc.) Performs various duties needed on the deck (e.g. stacking the net etc.) Table 3: Positions and Duties of Tuna boat crew As the ethnographic work of Michael Orbach describes, willingness to work and a strong back are enough to fulfill the job requirements for a general crew member.39 General crew members usually perform the simpler tasks on the boat. In Orbach’s study, he spent most of his time loading and unloading tuna that could weigh hundreds of pounds each. Occasionally the general crew may be called upon to fill almost any role if needed. Typically, general crew 39 For details of this account see Orbach (1977). members are only called to such tasks during low-activity times when their fellow fishers are occupied with other chores. The several years that the gear technicians spent as fishery observers, watching and sometimes assisting with tuna fishing, certainly prepared them to substitute into more specialized roles, such as skiff or speedboat driver. But it is important to consider that the fishers who normally fill these specialized positions have honed their skill for years, or even decades in the case of captain, mate, or deck boss. McNeely’s account of his first tuna fishing trip lends further insight into Coe’s statement. Early in the trip I pitched in and in time became one of the crew. I stood watch from 3 AM till daylight and took my turn peering through the binoculars for signs of fish. I…participated in all aspects of the fishing operations from setting of the gear to brailing aboard the fish for distribution to brine tanks and fast freezing…One of my first jobs was to throw sharks overboard. I was taught how to handle a 150 lb. shark and get it overboard with little effort. I would grab it by the tail, pull it to the rail and by using a twisting-rolling action, lift it off deck and get most of its weight over board. I would then turn [it] loose and let it slide into the water tail first.40 It is likely that McNeely’s experience was similar to that of Coe and his fellow gear technicians. As in Orbach’s account, McNeely’s first responsibility involved unskilled physical labor. Within the length of one cruise, he was performing the tasks of a general crew member. He even spent some time searching for tuna, which is the primary duty of the mast man, a highly skilled position. Because a captain hires only one mast man, who can not work all day every day, this duty is often shared among the crew. Participating in this way, certainly did not qualify McNeely to be the mast man proper and it is very doubtful that a captain would offer him this position. Mast men must have an exceptional ability to distinguish minute indicators of fish. In contrast when on the lookout for fish, the duty of the rest of the crew is to not miss the most obvious signs of tuna. An indulgent parent may allow a child to drive the family car along a deserted country road but not in heavy city traffic or on a busy highway and, likewise, the `fishers-in-training’ would not be called upon to fulfill specialist tasks in storms or cases of 40 This quote is taken from McNeely (2002), which is available from Lekelia Jenkins. major gear problems. It almost certainly follows that the gear technicians’ lack of contributory expertise in fishing gear and mechanical engineering would prevent them inventing conservation technologies that would be practical for commercial use in all probable situations. One former gear technician, Chuck Peters, recalled, “Most of the observer training was about biology and data collection…Dick McNeely showed the gear technicians how to cut and sew nets [paraphrased].” This comment suggests that the gear technicians did not enter into the position with contributory expertise in fishing gear or mechanical engineering. Furthermore, the basic training McNeely gave them would not have sufficed to impart this contributory expertise. In addition to their observer responsibilities, the gear technicians were meant to evaluate prototype conservation technologies and suggest new ones (Table 1). Unlike their previous job as observers, the gear technicians not only collected data, but often performed ad hoc analyses during research trips. Based on these analyses, the gear technicians would make and execute decisions on how to modify gear to improve performance, as well as decide whether or not to continue the evaluation. As McNeely described the invention process, much of the work was ‘“spur of the moment” inspiration that occurred while at sea but were later published as well thought out, laboratory built systems.’41 In essence, the gear technicians were prescribed the role of evaluator-inventor, serving as the first line of NMFS decision-making. Unfortunately the few years of on-boat experience gained as observers and then gear technicians, prepared them to be entry-level fishers not innovative gear specialists capable of revolutionizing the fishing gear and practices of an entire industry. Jim Coe was arguably the gear technician who had the greatest impact on reducing dolphin mortality through the advent of a conservation technology. Coe told me that he conceived the idea to use a rubber raft, mask, and snorkel to assist fishers in making certain that all dolphins exit the net during the backdown procedure. This innovation allows the fisher more time and greater visibility underwater to search for submerged dolphins. It also increased fishers’ safety by allowing them to see and avoid the sharks that are often present inside the purse-seine and had been known to attack rescuers, who routinely swam in the net assisting dolphins. NMFS was sufficiently impressed to require all tuna boats use a rubber raft, mask, and snorkel to facilitate dolphin rescue. This innovation would definitely be considered a 41 For more on this see McNeely (2002), which is available from Lekelia Jenkins. conservation technology, because it led directly to a reduction in dolphin mortality. However, it is atypical because does not affect any aspect of the fishing gear or fishing process that causes the bycatch problem. I suggest that Coe had innate but unrefined abilities that made him one of the most innovative gear technicians. Perrin confirms this in a letter he wrote about the superior performance of Coe as a gear technician. Significantly, his words refer only to Coe’s ability in matters electrical, not mechanical. Although having no formal background in electronics or bioacoustics, in a very short period before the cruise he [Coe] acquired sufficient knowledge and experience to successfully operate and maintain a complex system of recorders, amplifiers and transducers under difficult conditions at sea. Through improvisation, he was able to deal with a serious equipment malfunction during the cruise and thereby prevented premature termination of the experiments.42 Despite his innate abilities, Coe lacked the accompanying experience that would have given him contributory expertise in all three necessary areas (Figure 1), especially fishing gear and mechanical engineering. As I have shown, acquiring contributory expertise in these areas can take decades. While I believe Coe was on a path to becoming a gear expert, he had not achieved that level at the time. As further support for this assessment, there were no major advances in dolphin conservation technology during Coe’s tenure as head of the gear research program. 5. Perceptions of expertise The above profiles reveal the types of contributory and interactional expertise it is possible to attain in each role. Only Harold Medina could arguably be said to possess all the contributory expertise of a gear expert but, as I have shown, he is an exception among his fellow fishers. This case aside, to invent marine conservation technology, a collaborative effort, such as 42 This quote is taken from Perrin (1972), which is available from NOAA Fisheries Southwest Fishery Science Center. that one McNeely established, is essential. An interesting question, then, is why McNeely was able to establish collaborations with fishers while the gear technicians that he trained did not? The answer is a combination of the genuine lack of fishing experience of the gear technicians and the perception of a difference in status fostered by the institutional tensions mentioned at the outset. The captains that were involved in the gear development program were highliners. As the best in the industry, able to generate large profits through innovation and skillful fishing, they were highly respected by their fellow fishers. The very use of the term `highliner,’ along with other captains’ attempts to emulate them, indicate that innovative captains were viewed as a class apart, not only from gear technicians but even from other fishers. In addition, the highliners I spoke with affirmed that they viewed themselves as superior to the gear technicians in knowledge by referring to them as “college kids” who learned most of what they knew on the job from the industry Furthermore, fishers thought that the gear technicians, though they had more academic knowledge of animal biology and behavior, ignored the fishers’ experiential knowledge of animal behavior in relationship to fishing gear. As one highliner, who captained a boat used for gear testing, explained, The fishermen would try small changes. Each boat is different, so gear has to be adapted to each boat. NMFS wanted to make large changes…NMFS had a list of about 50 things they wanted to try and none of them worked. They tested lots of things and all of them were NMFS ideas. NMFS wanted to herd dolphins from within the net toward an opening in the net. I said that it wouldn't work and it didn't. The dolphins just dove under the boats and surfaced behind them… NMFS didn’t listen to fishermen, not even in writing [paraphrased]. Some captains seemed particularly averse to gear technicians, but not the equally young and college-educated fishery observers. One such captain was Harold Medina. NMFS praised Medina for his cooperation with observers: Captain Medina has been very concerned about porpoise conservation for many years. At his own initiative and expense he developed the “Medina Panel” which the National Marine Fisheries Service has now made mandatory for purse seines of fishing vessels. He has freely consulted with and advised our gear specialists on other porpoise saving techniques and methods. He has frequently volunteered to take Government porpoise observers on his vessel, the M/V Kerri M., even when it was inconvenient for him. For example last year when arrangements to place an observer on a boat leaving Panama had to be changed at the last minute, he came forward and volunteered to take the observer (this was the only such 1974 observer who was not placed by the random process). In all respects, he is an outstanding citizen and a credit to the tuna fishing industry.43 Nevertheless, despite Medina’s willingness to share his innovative knowledge and to accept fishery observers he remained unreceptive toward gear technicians. Medina allowed fishery observers to view the function of the Medina Panel on two separate trips but he refused to allow gear technicians on his boat. He told me: I never had a gear technician on my boat, but I did work with them…NMFS hired net experts to improve my idea, but fishermen were the only ones really making improvements….The gear technician’s learned on the job from the industry [paraphrased].” It seems that the captains were disgruntled by having these “kids” evaluate conservation technology prototypes, many of which were derived from the ideas of experienced fishers. By comparing this attitude with industry’s attitudes towards experienced gear specialists, one can see that this was not just a sweeping bias towards government employees. Rather, it was a focused bias against young inexperienced gear technicians, who the industry did not believe were qualified to have decision-making authority. Industry’s high opinion of McNeely is an example 43 Quote taken from Barham (1974b), which is available from NOAA Fisheries Southwest Fishery Science Center. of their contrasting attitude toward experienced government gear specialists. In my interview, McNeely proudly explained that he was so well accepted by industry that he was often the only government employee allowed in some of their meetings and industries high opinion of him is confirmed by documents.44 The tuna industry even requested that McNeely serve on the advisory council of the Porpoise Rescue Foundation, an industry research body. Interestingly, however, while the industry welcomed McNeely into a place of authority because of his experience, he struggled to find this same acceptance within NMFS because he lacked formal credentials. When McNeely moved to Seattle and became Chief of the Northwest Fishery Science Center gear research program, his colleagues did not readily accept him because he did not have a college degree. Despite his proven abilities, McNeely believed that his colleagues resented his authority over them. He felt he had to earn the respect that was routinely offered to his fellows simply because they had academic credentials. McNeely vividly retold this portion of his career, writing: I was well aware that my lack of a college degree lowered my status within a group of several hundred marine fishery scientists. Most all professional employees were college graduates and many had advanced Masters or Ph.D. degrees. Some were irritated (some were jealous) that I was the only one at the huge complex that had an official title of “Scientist.” Many respected and well published researchers had titles of Food Technologist, Chemist, Chemical Engineer, Oceanographer, Biologist, [Mammalogist], Embryologists, Mechanical and Electrical Engineer and a variety of other academic degree designations. However, only I could officially sign a document with the word “Scientist” after my name. It was tough enough to make out in this situation with no degree at all and even worse with a title that was wound salting! “Walking on eggs” was appropriate to my conduct in dealing with my peers. Most of my co-workers had showed little concern for my title and education deficiency as long as I was a temporary employee…However, after I became a permanent employee, spending considerable more time in the laboratory and less time at sea, I had to exercise even more caution in dealing with my peers. I made a 44 For more on this see Rothschild (1973), which is available from NOAA Fisheries Southwest Fishery Science Center. special effort to never use the “Scientist” title and usually referred to my position as a “gear development specialist”. From time to time, I was made aware of my situation by innuendo and well crafted remarks designed to “put me in my place.” 45 In their opposite ways, the cases of both McNeely and the gear technicians show that credentials are a misleading proxy for expertise. McNeely’s experience warranted that he have decision-making authority in the invention and development process. On the other hand, the college degree that seemed to be a hiring requirement for gear technicians did not confer any relevant expertise to justify their authority in the invention and development process. 6. Conclusion In this paper I have tried to describe expertise using the categories developed by Collins and Evans. In particular, I have found the contrast between no expertise and contributory expertise useful in understanding the actual contributions made by different parties, while I have found the ideas of interactional expertise and interactive ability useful in describing how certain individuals, such as McNeely, managed to coordinate the work of others with their own in order to produce valuable collective outcomes. I have shown that expertises needed to produce successful dolphin conservation innovations in the tuna fishing industry are contributory expertise in animal behavior and biology, fishing gear and procedures, and mechanical engineering. The four profiles illustrate that it may be rare to find this complex assemblage in one individual, such as Medina. Even McNeely, who was recognized as a gear specialist, did not possess all the needed expertises. Thus most attempts to invent dolphin conservation technology required a collective effort. Perrin’s profile shows that it is insufficient for a group of people to work collectively, if the full assemblage of required expertises is not represented. Furthermore, collective work will likely fail, if one or more of the parties does not have the interactional expertises to engage the other, such as in the failings of the fishers and gear technicians in Coe’s profile. A successful example of collaboration, McNeely’s profile aptly illustrates how his interactional expertise in 45 This quote is taken from McNeely (2002), which is available from Lekelia Jenkins. animal behavior and biology helped him integrate the expertise of dolphin biologists into his inventions, for instance the super apron. However, in complicated and emotionally charged situations such as this case study, interactional expertise is only one component of a successful collaboration. One or more parties must also have interactive ability, for example McNeely with his gregarious and inquisitive personality, and the willingness to interact. The difficulties between the gear technicians and tuna fishers show that willingness to interact can be directly tied to how parties perceive each others’ role in the interaction. This is a classic case of the tension between an institutional culture that depends on formal qualifications and one that values experience and expertise. Like the Wynne case study of Cumbrian sheep farmers, the expertise of individuals who lacked scientific credentials, although relevant was not adequately heeded in the decision-making process.46 On the other hand, this study lends no support to the idea that lay persons have any special kind of expertise; all the actors who made contributions in this domain were highly skilled and highly experienced. It follows, that if we are to understand how different expertises blend to produce a solution to a problem we must find a way to describe the character of expertise. We must find a way that is independent of attributions associated by others with certain social groups – I have shown how misleading this can be. For example, NMFS personnel assumed that most fishers were de facto gear experts capable of inventing conservation technologies, when in fact most were still learning about the gear. We must find a way that is also independent of the political or institutional nexus from which expertise emerges – I have shown how damaging this can be. For example, it is revealed in the distrust and sweeping judgments on the part of both NMFS personnel and fishers that led to tensions between the two parties. In this atmosphere the innate abilities of Coe were subsumed by the fishers’ general negative attitude toward the “college kids.” Thus Coe’s innate abilities were less likely to be nurtured because fishers with relevant expertise, such as Medina, refused to work closely with the gear technicians. We must find a way that is also independent of the qualifications of the bearers of expertise. I have shown how irrelevant this can be, for instance, McNeely’s fitness for positions being determined by his lack of degree rather than his years of formal and informal education and experience and the gear technicians being given authority based on their degrees that was not warranted by their 46 For more on this see Wynne (1989) knowledge. This new way of characterizing expertise must assess individuals’ expertise in terms of their knowledge and experience, and must not depend on qualifications or institutional affiliations as proxies for a direct analysis. References Alverson, D. L. (1972). Porpoise committee--a progress report. Anonymous (1971a). Pity the Poor Porpoise. Anonymous (1971b). Summary - porpoise/tuna situation. Barham, E. (1974a). Medina panel mesh size: factors pertaining to proposed regulations. Barham, E. (1974b). Tuna fisherman of the year award. Bernard, H. R. (2002). Research Methods in Anthropology: Qualitative and Quantitative Approaches. Walnut Creek, CA: Altamira Press. Coe, J., & Sousa, G. (1972). Removing porpoise from a tuna purse seine. Marine Fisheries Review, 1972 Nov.-Dec., 15-19. Coe, J. M., Holts, D. B., Butler, R. W. (1984). The tuna-porpoise problem: NMFS dolphin mortality reduction research, 1970-1981. Marine Fisheries Review, 46, 18-33. Collins, H. M., & Evans, R. (2002). The third wave of science studies: Studies of expertise and experience. Social Studies of Science, 32, 235-296. Collins, H. M., & Evans, R. (2004). Periodic Table of Expertise. Collins, H. M., & Evans, R. (2007). Rethinking Expertise. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. Department of Commerce (1974). Report to the congress on the research and development program to reduce the incidental take of marine mammals: October 21, 1972 through October 20, 1974. Gehres, L. E. (1971). Holt, D. (1973). Preliminary report of porpoise mortality directly related to gear, gear malfunctions and techniques presently being used in the Eastern Tropical Pacific tuna purse seine fishery. Joseph, J. (1994). The tuna-dolphin controversy in the eastern pacific ocean: Biological, economic, and political impacts. Ocean Development and International Law, 25, 1-30. Joseph, J., & Greenough, J. W. (1979). International Management of Tuna, Porpoise, and Billfish: Biological, Legal, and Political Aspects. Seattle: University of Washington Press. McNeely, R. L. (1961). The purse seine revolution in tuna fishing. McNeely, R. L. (2002). Little Squeak from Dunbar (Memoirs of Richard L. McNeely). NMFS (1971). Result of meeting between representatives of the National Marine Fisheries Service and the tuna industry on September 9, 1971. NMFS (1977). Monthly report - July and August 1977. NRC (1992). Dolphins and the Tuna Industry. Washington DC: National Academy Press. Orbach, M. K. (1977). Hunters, Seamen and Entrepreneurs: The Tuna Seinermen of San Diego. Berkley: University of California Press. Perrin, W. (1970). Quarterly program progress report: assessment and alleviation of porpoise mortality: January 1 - March 31, 1970. Perrin, W. (1971a). Quarterly project progress report: development and improvement in fishing strategy. Perrin, W. (1971b). Quarterly project progress report: development and improvement in fishing strategy: January 1 - March 31, 1971. Perrin, W. (1971c). Summary -- porpoise/tuna situation. Perrin, W. (1972). Superior performance by D. B. Holts and J. M. Coe. Rothschild, B. J. (1973). Porpoises and tuna policy. Strauss, A. L. C., Juliet (1998). Basics of Qualitative Research: Techniques and Procedures for Developing Grounded Theory (2nd ed.). Thousand Oaks: SAGE Publications, Inc. Wynne, B. (1989). Sheep farming after Chernobyl: A case study in communicating scientific information. Environmental Magazine, 31, 33-39.