Against the Grain: Cultural Diversity, the Writing Center, and the

advertisement

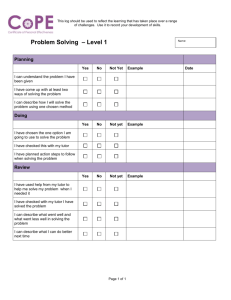

Manning 1 Patrick Manning Writing Center Internship Prof. Jean Grace and Geeta Kothari April 10, 2005 Against the Grain: Cultural Diversity, the Writing Center, and the University Ashley held out the essay she had written for Seminar in Composition. The assignment had requested that she analyze an aspect of her own life in the same way one of her readings did. She chose to write about her interactions with money and how, ultimately, through education of the processes involved with finances, anyone could become economically successful. That was her thesis, but that wasn’t her idea. At first, I asked her what she wanted to discuss; what were her concerns about the essay. Organization, punctuation, and commas…always commas. Focusing on how she had organized her ideas, I began reading here essay. She used anecdotes about her childhood, her job as a bank teller and her experiences with the wealthy, to construct an essay that was clear and well-organized. However, some of the anecdotes seemed off topic: she had told a story about how she was always excited when her father gave her two quarters for the candy store instead of one. I asked her how it related to the idea of financial education. There was a sudden shift in the tutorial. Ashley subtly hinted at an underlying issue: her working class situation and how that affected her life at college and in society. I noticed the hint and asked her to expand on that idea. She articulated feelings of inadequacy in the presence of wealthy friends, anger at frivolous spending, frustration Manning 2 towards political agendas favoring the rich, the difficulty of receiving financial aid to attend the University of Pittsburgh. I informed her ideas with my similar cultural and economic background. Suddenly, we were in it, the holy grail of composition, Mary Louise Pratt’s article I had read, discussed, cited—I had found myself in the contact zone, the place where our cultural expressions had met. We were discussing the politics of University life, the wealthy, the educated and how it related. She was forced to move to the North Side of the city to save money. She worked, however, on the South Side and attended the University of Pittsburgh half way in between. I wrote as she spoke. I grouped ideas, drew lines and boxes, underlined items and circled others: the paper was a piece of brainstorming genius. When we had finished with our powerful discussion of class in the University, I showed her the sheet of paper and asked her to connect these ideas with the assignment at hand. She lifted the paper and stared down at it. “I’m not sure I’ll have time to change it this much. It’s due tomorrow.” My energy was spent. Deflated as I was, I turned to my LB Brief and pointed out how to use commas in a series. But was that the best alternative? Should I have provoked further into the issue Ashley had seemed to want to ignore? Was I functioning as an agent of the University and not as an agent of academic discourse? And, furthermore, which one should I have been? Writing centers, by defining themselves as places of knowledge formation, need to become culturally diverse and sensitive; they must fight against the attempts made by the university to standardize students according to white middle-class values. Manning 3 The Writing Center’s self-conception promotes writing as a process. As North points out, the center’s “job is to produce better writers, not better writing” (69). However, North’s discussion is too narrowly focused on the individual: it borders on expressionistic in placing knowledge formation as an act that is solely individual. In doing so, it “ignores the extent to which social group determines what action the individual can take within society” (Hobson 104). It places the writing process outside of its cultural context. By lifting writing above culture, it allows for the creation of a rightwrong dichotomy that negates certain ways of thinking and writing. Because “writing is a social artifact” it must be honored as such in the center (Bruffee 211). Writing cannot be divorced from its cultural context; it has “no meaning, use, or currency apart from…interpretation” (Chafe 396). The interaction of tutor and tutee creates this cultural and social aspect of writing and creating; it works towards the ideal of creating better writers. However, remaining culturally sensitive and promoting diversity can be hindered by the structure created by the University. Because we exist within a University, we are subject to and products of both its history and its present. We can view the “process of education as a microcosm of the power relations and oppositional politics that exist in any society” (Murphy 276). The same inequalities existing in our society (race, gender, religion, ethnicity) exist within the educational system. With the same inequalities comes the same domination by the White, middle-class Americans. Using its power, the ideals of this group become mainstream, the “right” half of the dichotomy. With this power, knowledge again is taken out of its cultural realm: there becomes a right (white) and a wrong (other). As such, “the contextual nature of discourse and the Manning 4 malleability of language” is ignored (Hobson 103). Positivism, the I’m-right-you’rewrong mentality, takes its place; the hegemony prescribes knowledge (Hobson 101). Cultural and social ways of constructing knowledge are no longer valid; these dynamics are essential to writing center practice. When these practices become devalued, writing centers become threatened. A study conducted by Agnew and McLaughlin at Georgia Southern University found that the basic writing program precluded many African-Americans from continuing education. Students were placed into the new basic writing program based on entrance exams and given three chances to pass the course. If the student failed the third time, she could not attend any public university in Georgia for three years. To pass the course, the student had to write an impromptu essay that was judged by a group of graders. Rowena, one of the focal points of the research, was an African-American woman. She took the course three times, finally passing on the third time. Her first two failing essays exhibited a strong voice and narrative style. There were “AAVE [African-American Vernacular English] features that contribute to the student’s voice and ownership of the text” (Agnew 93). However, she achieved a passing grade only when this style was eradicated and the acceptable style adopted: generalization followed by specification; three-pronged thesis; a distance between writer and text, etc. The system had successfully changed Rowena’s writing style into the acceptable, standardized work we as writing centers should work to dispel. This study proves Smitherman’s assertion that “the speech of blacks, the poor, and other powerless groups is used as a weapon to deny them access to full participation in society” (Agnew 86). Because writing is such a personal endeavor, because it depends Manning 5 on cultural histories, because it reflects an individualistic view of the world, it cannot be standardized. If it is, we lose the richness of the art. But how can we combat these engrained notions of education as a force of “standardization, stratification and systemization” (Grimm 34)? Writing centers need to value cultural diversity and work to promote challenging and competing understandings of the world. “Using writing…deeply affect[s] world view and being in the world” (Chafe 392); writing centers need to recognize the power of creating a piece of writing. Kilborn offers us only superficial ways of understanding cultural diversity: I and members of my staff have attended such events as the Chinese New Year; poetry readings during African-American Awareness Week; banquets, potlucks, and pow wows; and panel discussion, teleconferences, and speakers on such topics as racism and racial violence, global awareness, the “Making of Dances with Wolves,” and the Persian Gulf War (395). While she is undoubtedly well intended, these attempts to promote cultural diversity may fall short of its goal. It seems the intention of such endeavors is to educate people on as many different cultures as possible but it does nothing to teach people how to interact with those cultures. Furthermore, it cannot be the job of the tutor to be an expert on every different world culture. It is the job of the tutor to engage with different cultures, not to be an expert. To defeat the engrained hegemonic ideals of the university, more deeply rooted concepts need to be established. Authentic listening is a key factor in achieving Manning 6 culturally sensitive and diverse tutorials. “Authentic listening…requires…a ‘dwelling’ in another’s thought with a part of our mind suspended, recognizing ‘that we share in both the problem and solution without being able to escape into neutral and unrelated spaces” (Grimm 69). This technique requires the tutor to become as invested in the work as is the writer; it demands interaction and cultural interpretation. It suggests, though, that the tutor needs to divorce herself from her own cultural background in ‘suspending’ her own mind. This can prove problematic: the tutor’s cultural experience is as relevant as the writer. It is essential for the tutor to remain within her own cultural mindset to better inform the text. For authentic listening to be successful, the tutor must remain sensitive to the writer’s cultural knowledge. Authentic listening, practically speaking, requires that the tutor remain open and alert. Beyond that, though, it requires a willingness to engage, to commit, and to involve oneself with the writing. In my tutoring session with Ashley, I picked up on a subtle hint about economic struggle. I also allowed my own feelings of economic disparity to become involved in the writing. Despite the session’s eventual outcome, we successfully entered into a discussion of greater cultural significance. Because we both shared in “the problem and solution,” we invested more into the session. Sharing in both the problem and solution opens the doors to the contact zone. Through authentic listening, we can create an organic place for cultural discussion to exist. In Anne DiPardo’s essay “’Whispers of Coming and Going’: Lessons from Fannie,” she illustrates a scenario in which the tutor failed to recognize subtle hints the tutee used. The tutee, Fannie, had been raised on a Navajo Reservation; her schooling included a boarding school in that forbade her native language, and her cultural Manning 7 assumptions, i.e., collaboration as important to the learning process, were subservient to ideas of individualism (DiPardo 352). In effect, her cultural identity had been devalued by her schooling. Attending college at a predominantly all white university, Fannie began a semester long tutor sessions with Morgan, an African-American student (357). During one session, Morgan chose a minimalist approach to try to help Fannie out of her writer’s block. And Fannie, armed with Navajo ideals and heritage, discussed writing an essay about values (360). Throughout the session, Morgan tried not to speak too much; but, she also does not listen authentically. Morgan steers the fragmented pieces of Fannie’s statements, one’s that in print seem to be suggesting a culturally sensitive subject of Navajo relation to the Earth and subsequent conquer by Western society, towards “commonplace environmental concerns” (DiPardo 361). Fannie hints repeatedly at the importance of the land: never does she overtly mention pollution or deforestation. And, in Morgan’s defense, she may not be well versed in the niceties of Navajo culture. But that is exactly the reason the tutor is required to listen, and listen intently, authentically, to the student’s statements. Morgan, however, should not have only listened. Authentic listening does not exclude interaction; in fact, it requires it. Thus, the process of authentic listening comes in conflict with the minimalist tutoring strategy. Brooks suggests “the student, not the tutor, should ‘own’ the paper and take full responsibility for it” (220). Following this technique precludes the student from entering the space where he “share[s] in both the problem and the solution”; in effect, it allows the student to escape to neutral ground negating Brufee’s notion of writing as a social artifact. Suddenly, the entire process is placed on the writer. I can hear my seventh grade teacher gasping even as I write: Of Manning 8 course the writer is responsible for her own writing. And I will agree, to a certain extent. But writing is a cultural phenomenon: it requires interaction. It’s a cultural artifact because “no written materials have meaning, use, or currency apart from oral interpretation” (Chafe 396). In other words, writing carries no weight of its own without the interpretation of readers, without a cultural audience. Authentic listening requires both tutor and tutee to remain vulnerable. This vulnerability creates an environment where “ideas and identities [are put] on the line” (Pratt 617). Because “everyone [has] a stake” in the learning experience, we create knowledge in a way that challenges the structure we exist in. It is not a prescriptive transfer of knowledge; it is a culturally based, dialogue driven creation of knowledge. Mary Louise Pratt’s discussion of the contact zone provides for a culturally based creation of knowledge: it creates a space where learning intersects personal investment. Students no longer are told what to think. Rather, as discussed above, knowledge is created. However, constructing contact zones does not fully serve the student: to engage in discourse means that all parties must be invested in the outcome. Trying to create an inorganic space to “grapple” with ideas results in a mundane and unproductive session. In Westbrook’s case study of an independent writing group, she found organically occurring contact zones. Creating such spaces precludes productivity because no one has “anything at stake in preserving [it] since it is not a space to which anyone owes much allegiance” (Westbrook 233). This is precisely why authentic listening is paramount in creating spaces of cultural discourse. Through this practice, both tutor and tutee have become involved with the writing—both have invested in it. As such, it creates a contact zone because it is of their creation and they owe it the necessary “allegiance.” Manning 9 The contact zone, however, comes into conflict with the university structure. By challenging traditional notions of learning, the contact zone creates tension. Moreover, as in my session with Ashley, it doesn’t always result in success; it, too, can become subject to the system (“It’s due tomorrow”). Who then, are we responsible to? Stephen North suggests, “in all instances the student must understand that [writing center tutors] support the teacher’s position” (72). In doing so, though, aren’t we negating the “student-centered” model of tutoring? By supporting the teachers without question, we become part of the system that we should work to change. Precisely because writing shapes world view, we cannot passively submit to notions of standardization. As in Rowena’s case, who among us would tell her to reject her cultural intuitions? If we were to do so, we would be promoting the whiteway-is-better ideal. Through rejecting certain cultural expressions, we position them at the bottom end of a hierarchy—a lower class than our more intellectual, obviously better system. The writing center needs to be a fortress against notions of inequality. Writing is cultural; the writing center supports writing. The only conclusion is that the center promotes writing as a cultural agent, a way of maintaining one’s own culture despite the force to reject it. In doing so, the center cannot become merely an agent of the system— it cannot passively accept writing assignments that preclude cultural expression. In fact, it is its duty to question the authority promoting it. This is not to say that Standard English has no place in academia. After all, despite our utopian ideals of cultural pluralism and acceptance, our society still works within the confines of the standardized language. But, as much as AAVE, Spanglish and Manning 10 other dialect speakers are required to learn the mainstream’s language for communication, the mainstream needs to learn theirs. In asserting the superiority of Standard English, we cast these other languages as lesser. Doing so also assumes cultural dominance: the language used is always the language of the dominant, the colonizers. Pursuing a liberal cultural agenda, it becomes necessary to regard other dialects of English as worthy of use and study. Writing Centers need to pursue a culturally diverse and sensitive agenda. We must nurture and challenge writing within its cultural realm and be willing to challenge our institution. Only through challenging the hegemony of the University can we fully realize the social and cultural significance of writing as art. Manning 11 Works Cited Agnew, Eleanor and Margaret McLaughlin. “Those Crazy Gates and How They Swing: Tracking the System that Tracks African-American Students.” Mainstreaming Basic Writers: politics and Pedagogies of Access. Ed. Gerri McNenny. Mahwah: Lawrence Erlbaum, 2001. Bruffee, Kenneth A. “Peer tutoring and the Conversation of Mankind.” The Allyn and Bacon Guide to Writing Center Theory and Practice. Eds. Robert W. Barnett and Jacob S. Blumner. Boston: Allyn and Bacon, 2001. Chafe, Wallace and Deborah Tannen. “The Relation Between Written and Spoken Language.” Annual review of Anthropology Vol16 (1987): 383-407. DiPardo, Anne. “‘Whispers of Coming and going’: Lessons from Fannie.” The Allyn and Bacon Guide to Writing Center Theory and Practice. Eds. Robert W. Barnett and Jacob S. Blumner. Boston: Sllyn and Bacon, 2001. Grimm, Nancy Maloney. Good Intentions: Writing Center Work for Postmodern Times. Heinemann: Portsmouth, 1999. Hobson, Eric H. “Maintaining Our Balance: Walking the Tightrope of Competing Epistemologies.” The Allyn and Bacon Guide to Writing Center Theory and Practice. Eds. Robert W. Barnett and Jacob S. Blumner. Boston: Sllyn and Bacon, 2001. Manning 12 Kilborn, Judith. “Cultural Diversity in the Writing Center; Defining Ourselves and Our Challenges.” The Allyn and Bacon Guide to Writing Center Theory and Practice. Eds. Robert W. Barnett and Jacob S. Blumner. Boston: Sllyn and Bacon, 2001. North, Stephen M. “The Idea of a Writing Center.” The Allyn and Bacon Guide to Writing Center Theory and Practice. Eds. Robert W. Barnett and Jacob S. Blumner. Boston: Sllyn and Bacon, 2001. Pratt, Mary Louise. “Arts of the Contact Zone.” Ways of Reading: An Anthology for Writers. Eds. David Bratholomae and Anthony Petrosky. Boston: Bedford/St. Martin, 2002. 604-620. Westbrook, Evelyn. “Community, Collaboration, and conflict: The Community Writing Group as Contact Zone.” Writing Group Inside and Outside the Classroom. Eds. Beverly J. Moss, Nels P. Highberg, Melissa Nicolas. Mahwah: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Publishers, 2004. 229-248.