Blood pressure reactions to account stress and future blood

advertisement

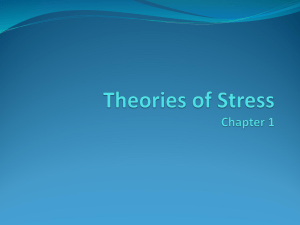

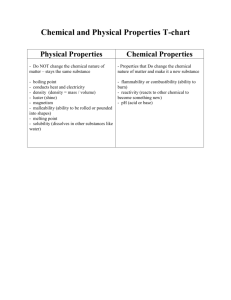

Pre-print. Cite as Blood Pressure Reactions to Acute Mental Stress and Future Blood Pressure Status: Data From the 12-Year FollowUp of the West of Scotland Study Carroll, D., Phillips, A., Der, G., Hunt, K. & Benzeval, M. 1 Nov 2011 In : Psychosomatic Medicine. 73, 9, p. 737-742 Blood pressure reactions to acute mental stress and future blood pressure status: Data from the 12-year follow-up in the West of Scotland Study Running head: Stress reactivity and future blood pressure Douglas Carroll, PhDa, Anna C. Phillips, PhDa, Geoff Der, PhDb, Kate Hunt, PhDb, and Michaela Benzeval, MScb a School of Sport and Exercise Sciences, University of Birmingham, Birmingham, England b MRC/CSO Social and Public Health Unit, University of Glasgow, Glasgow, Scotland Words:3961 Tables:2 Figures:1 Address correspondence to: Douglas Carroll, PhD, School of Sport and Exercise Sciences, University of Birmingham, Birmingham B15 2TT, England. E-mail carrolld@bham.ac.uk 1 Pre-print. Cite as Blood Pressure Reactions to Acute Mental Stress and Future Blood Pressure Status: Data From the 12-Year FollowUp of the West of Scotland Study Carroll, D., Phillips, A., Der, G., Hunt, K. & Benzeval, M. 1 Nov 2011 In : Psychosomatic Medicine. 73, 9, p. 737-742 Blood pressure reactions to acute mental stress and future blood pressure: Data from the 12-year follow-up in the West of Scotland Study Douglas Carroll, Anna C. Phillips, Geoff Der, Kate Hunt, and Michaela Benzeval 2 Pre-print. Cite as Blood Pressure Reactions to Acute Mental Stress and Future Blood Pressure Status: Data From the 12-Year FollowUp of the West of Scotland Study Carroll, D., Phillips, A., Der, G., Hunt, K. & Benzeval, M. 1 Nov 2011 In : Psychosomatic Medicine. 73, 9, p. 737-742 Abstract Objective: The reactivity hypothesis was tested using data from a 12 year follow-up of blood pressure. It was examined whether blood pressure reactions to acute mental stress predicted future blood pressure resting levels, as well as the temporal drift in resting blood pressure, and whether the prediction was affected by sex, age, and socioeconomic status. Methods: Resting blood pressure was recorded at an initial baseline and in response to a mental stress task. Twelve years later resting blood pressure was again assessed. Data were available for 1196 participants, comprising, at the time of stress testing, 437 24-year olds, 503 44-year olds, and 254 63-year olds, 645 women and 551 men, and 531 were from manual socioeconomic households and 661 non-manual socioeconomic households. Results: In multivariate linear regression models, adjusting for a number of potential confounders, systolic blood pressure reactivity positively predicted future resting systolic blood pressure, as well as the upward drift in systolic blood pressure over the 12 years, β = .10, p < .001 in both cases. The effect sizes were smaller than those reported from an earlier 5-year follow-up. The analogous associations for diastolic blood pressure reactivity were not statistically significant. In multivariate logistic regression, high systolic blood pressure reactivity was associated with an increased risk of being hypertensive 12 years later, OR = 1.03, 95%CI 1.01 – 1.04, p < .001. Conclusions: The present findings that greater reactivity is associated with higher future resting blood pressure, more upward drift in resting blood pressure, and future = hypertension provide support for the reactivity hypothesis. 3 Pre-print. Cite as Blood Pressure Reactions to Acute Mental Stress and Future Blood Pressure Status: Data From the 12-Year FollowUp of the West of Scotland Study Carroll, D., Phillips, A., Der, G., Hunt, K. & Benzeval, M. 1 Nov 2011 In : Psychosomatic Medicine. 73, 9, p. 737-742 Key words: Systolic blood pressure; diastolic blood pressure; reactivity; acute mental stress; hypertension; prospective study. DBP = diastolic blood pressure; PASAT = paced auditory serial addition test; SBP = systolic blood pressure 4 Pre-print. Cite as Blood Pressure Reactions to Acute Mental Stress and Future Blood Pressure Status: Data From the 12-Year FollowUp of the West of Scotland Study Carroll, D., Phillips, A., Der, G., Hunt, K. & Benzeval, M. 1 Nov 2011 In : Psychosomatic Medicine. 73, 9, p. 737-742 INTRODUCTION The reactivity hypothesis has proved to be both extremely influential and exceptionally durable (1, 2); at its simplest, it posits that large magnitude cardiovascular reactions to acute psychological stress play a role in the development of cardiovascular pathology in general and high blood pressure in particular (3-5). It is certainly the case that the cardiovascular adjustments observed during acute psychological stress differ from those that occur during physical exertion in that the latter are closely coupled with the metabolic demands of motor behaviour whereas the former are apparently uncoupled from the energy demands of behaviour and might be properly regarded as metabolically exaggerated (6). Thus, it is easy to see why, in contrast to the biologically appropriate and health enhancing adjustments during physical activity, large magnitude cardiovascular reactions to psychological stress might be considered pathophysiological. Although the original reactivity hypothesis is not without its critics (7), direct evidence in support comes from a number of large scale cross-sectional and prospective observational studies that attest to positive associations between the magnitude of cardiovascular reactions to acute psychological stress tasks and future blood pressure status (8-18), markers of systemic atherosclerosis (19-22), and left ventricular mass and/or hypertrophy of the heart (23-25). The effect sizes are generally small but the evidence is certainly consistent with the main tenets of the reactivity hypothesis (26). Previously, we reported prospective analyses of data from the West of Scotland Study (8). Blood pressure was measured at rest and in response to an acute mental stress task; resting blood pressure was assessed five years later. Greater systolic blood pressure stress reactivity was associated with 5-year follow-up resting systolic blood pressure and 5 Pre-print. Cite as Blood Pressure Reactions to Acute Mental Stress and Future Blood Pressure Status: Data From the 12-Year FollowUp of the West of Scotland Study Carroll, D., Phillips, A., Der, G., Hunt, K. & Benzeval, M. 1 Nov 2011 In : Psychosomatic Medicine. 73, 9, p. 737-742 also with the upward drift in resting systolic blood pressure over time. The magnitude of the prediction appeared to vary with sex and socioeconomic position. In the present study, we report the outcome of analyses of data from a subsequent follow-up assessment of blood pressure within the West of Scotland Study, 12 years on from the stress testing session. This affords further opportunity to test the reactivity hypothesis with a more protracted follow-up than the majority of other previous studies using mental stress tasks. It is difficult to discern from previous studies the effect of duration of follow-up on the prognostic significance of reactivity for future blood pressure status. Although studies have varied in follow-up duration, they also vary in many other ways, such as the nature and provocativeness of the stress task and the population studied. This makes it problematic to attribute variations in the magnitude of the association been reactivity and cardiovascular outcomes to variations in length of follow-up. However, one study, Whitehall II, has separately reported on a 5-year (9) and 10-year follow-up (10). Systolic blood pressure reactions to mental stress afforded the same magnitude of independent prediction of systolic blood pressure levels at both follow-ups. It has been contended that the most consistent and robust associations between reactivity and future blood pressure status emerge from studies with younger samples and that a preponderance of older participants in some prospective studies is responsible for the modest effects seen (27). The present study, because of the three narrow age cohorts recruited, is perhaps uniquely placed to consider age variations in the predictive power of reactivity on cardiovascular outcomes. Finally, the current analysis also examines the reactivity hypothesis in the context of a dataset that allows adjustment for a range of potential confounding variables. 6 Pre-print. Cite as Blood Pressure Reactions to Acute Mental Stress and Future Blood Pressure Status: Data From the 12-Year FollowUp of the West of Scotland Study Carroll, D., Phillips, A., Der, G., Hunt, K. & Benzeval, M. 1 Nov 2011 In : Psychosomatic Medicine. 73, 9, p. 737-742 MATERIALS AND METHODS Participants Data were collected as part of the West of Scotland Twenty-07 Study. Participants were all from Glasgow and surrounding areas in Scotland and have been followed up at intervals since the initial baseline survey in 1987 (28). Full details of the sampling methodology and the structure of the sample is provided elsewhere (29). The analyses here are of data from the third follow-up (referred to as baseline hereafter), at which participants underwent standard cardiovascular stress testing, and from the fifth and final follow-up, during which resting blood pressure was measured. A characteristic feature of the sample is that it comprises three distinct age cohorts, the rationale for which is again provided elsewhere (30). The mean (SD) lag between baseline and the follow-up was 12.4 (0.40) years. The effective sample size for the present analyses, i.e., those who had complete cardiovascular data at both time points was 1196 (73% of those for whom reactivity data were available at baseline). The reasons for non-participation at follow-up were: ‘refusal to participate’ 38%; ‘died/incapacitated’ 33%; ‘moved house/not contactable’ 29%. At baseline the mean (SD) age was 41.1 (0.43) years and there were 437 (37%) 24-year olds, 503 (42%) 44-year olds, and 254 (21%) 63-year olds. There were 645 (55%) women and 551 (45%) men, and 531 (45%) were from manual occupational households and 661 (55%) non-manual occupational households. Ninetyeight (8%) reported taking antihypertensive medication at baseline and the mean (SD) body mass index of the sample at the time was 25.6 (4.11) kg/m2. Apparatus and Procedure 7 Pre-print. Cite as Blood Pressure Reactions to Acute Mental Stress and Future Blood Pressure Status: Data From the 12-Year FollowUp of the West of Scotland Study Carroll, D., Phillips, A., Der, G., Hunt, K. & Benzeval, M. 1 Nov 2011 In : Psychosomatic Medicine. 73, 9, p. 737-742 Testing sessions were conducted by trained nurses in a quiet room in the participants’ homes. Demographic and medication status at baseline was obtained by questionnaire. Household socioeconomic status was characterize as manual and non-manual from the occupational status of the head of household, using the Registrar General classification system (30). Participants were asked whether they were taking any blood pressure lowering medication and their medicine repositories checked for confirmation. Height and weight was measured and body mass index computed. The acute stress task was the paced auditory serial arithmetic test (PASAT), which has been shown in numerous studies to reliably perturb the cardiovascular system (31, 32), and to demonstrate good test-retest reliability (33). The nurses were all trained in administering the PASAT by the same trainer and followed a written protocol. The test comprised a series of single digit numbers presented by audiotape. Participants were instructed by the nurse to add sequential number pairs, while at the same time retaining the second of the pair in memory to add to the next number presented. Answers were given orally and the number of correct answers was recorded by the nurse, who remained in the room, as a measure of performance. The first sequence of 30 numbers was presented at a rate of one every 4 seconds, and the second at one every 2 seconds. The task lasted 3 minutes. Only those who registered a score on the PASAT were included in the analyses. Of a possible score of 60, the mean (SD) score was 44.6 (9.09). Systolic blood pressure (SBP) and diastolic blood pressure (DBP) were recorded using a brachial cuff and a semi-automatic sphymomanometer (model 705CP, Omron, Weymouth, UK). This blood pressure measuring device is recommended by the European Society of Hypertension (34). After questionnaire completion (taking at least 8 Pre-print. Cite as Blood Pressure Reactions to Acute Mental Stress and Future Blood Pressure Status: Data From the 12-Year FollowUp of the West of Scotland Study Carroll, D., Phillips, A., Der, G., Hunt, K. & Benzeval, M. 1 Nov 2011 In : Psychosomatic Medicine. 73, 9, p. 737-742 an hour), there was a formal 5-minute period of relaxed sitting, at the end of which a resting baseline reading was taken. Task instructions were then given and participants allowed a brief practice to ensure they understood the requirements of the PASAT. Two further blood pressure readings were then taken, the first initiated 20 seconds into the task (during the slower sequence of numbers) and the second initiated 110 seconds later (during the faster sequence of numbers). The two task readings were averaged and the resting baseline value subtracted, to yield reactivity measures for SBP and DBP. At the follow-up, 12 years later, resting blood pressure was again recorded using the Omron in the participants’ homes by nurses. As before, blood pressure measurement followed the same lengthy questionnaire protocol and 5 minutes of relaxed sitting. Three measurements were taken approximately 1 minute apart; the second two measurements, one from the right arm and one from the left, were averaged as the measure of resting blood pressure. The following criteria were used to define hypertension at the 12 year follow-up: being on antihypertensive medication, or resting systolic blood pressure ≥ 140mmHg, or resting diastolic blood pressure ≥ 90mmHg. Statistical Analyses Repeated measures ANOVA was used to confirm that the PASAT significantly increased SBP and DBP and to examine the drift in resting blood pressure between baseline assessment and final follow-up 12 years later. η2 was adopted as a measure of effect size. The association between SBP and DBP reactivity at baseline and resting SBP and DBP at the fifth and final follow-up were examined by correlation and then by multiple linear regression using the following additional covariates: age cohort, sex, 9 Pre-print. Cite as Blood Pressure Reactions to Acute Mental Stress and Future Blood Pressure Status: Data From the 12-Year FollowUp of the West of Scotland Study Carroll, D., Phillips, A., Der, G., Hunt, K. & Benzeval, M. 1 Nov 2011 In : Psychosomatic Medicine. 73, 9, p. 737-742 PASAT performance, socioeconomic status at baseline, resting blood pressure at baseline, taking blood pressure medication at baseline, and body mass index at baseline. The covariates were always entered at step 1 and reactivity at step 2. Initial focus for the regression analyses was the whole sample. Where significant overall associations emerged, these were followed by subgroup analyses; analogous regression models were tested separately for women and men, manual and non-manual socioeconomic group, and the three age cohorts. Following on from our previous analyses (8), similar analyses were performed on resting blood pressure drift over the 12 years between assessments (i.e., resting blood pressure at the fifth follow-up minus resting blood pressure at baseline). From the linear regression analyses, we report β, the standardized regression coefficient. Finally, the association between SBP and DBP reactivity and hypertension was examined using logistic regression, first testing unadjusted models and then testing models adjusting for the variables listed above. RESULTS The summary data for the 1647 participants who successfully underwent stress testing at baseline are presented in Table 1. Those (N = 1196) who were available at 12-year follow-up did not differ from those (N = 451) who were not available in either SBP reactivity (p = .72) or DBP reactivity (p = .53); this was also the case for comparisons involving specific reasons for dropping out. [Insert Table 1 about here] 10 Pre-print. Cite as Blood Pressure Reactions to Acute Mental Stress and Future Blood Pressure Status: Data From the 12-Year FollowUp of the West of Scotland Study Carroll, D., Phillips, A., Der, G., Hunt, K. & Benzeval, M. 1 Nov 2011 In : Psychosomatic Medicine. 73, 9, p. 737-742 Blood pressure reactions to acute stress Table 1 presents the means and SD for the key blood pressure variables. The increases in SBP and DBP to the stress task were statistically significant, F(1, 1195) = 1197.76, p < .001, η2 = .501, and F(1, 1195) = 753.28, p < .001, η2 = .387. The mean (SD) upward drift in resting SBP over 12 years was 4.10 (22.68) mmHg; this increase was statistically significant, F(1, 1195) = 39.23, p < .001, η2 = .032. The drift for DBP, 0.84 (13.79) mmHg was much more modest but still statistically significant, F(1, 1195) = 4.47, p = .04, η2 = .004. [Insert Table 2 about here] Reactivity and resting blood pressure 12 years later SBP reactivity was positively correlated with resting SBP 12 years later, r (1194) = .08, p = .004; there was no such correlation between DBP reactivity and subsequent resting DBP, p = .24. We then tested a hierarchical linear regression model with resting SBP at the fifth, i.e., 12-year, follow-up as the dependent variable with the following covariates, age cohort, sex, PASAT performance, socioeconomic status at baseline, resting blood pressure at baseline, taking blood pressure medication at baseline, and body mass index at baseline, entered at step one and SBP reactivity at step 2. In this model, SBP reactivity emerged as a significant predictor of resting SBP at the 12-year follow-up, β = .10, p < .001, ∆R2 = .010: the greater the SBP reactivity, then, the higher the subsequent resting SBP. The other significant predictors of 12-year resting SBP in this model were: higher initial resting SBP, β = .30, p < .001; being in the older age cohort, β = .21, p < .001; having a larger body mass index, β = .08, p = .003; being male, β = .13, p 11 Pre-print. Cite as Blood Pressure Reactions to Acute Mental Stress and Future Blood Pressure Status: Data From the 12-Year FollowUp of the West of Scotland Study Carroll, D., Phillips, A., Der, G., Hunt, K. & Benzeval, M. 1 Nov 2011 In : Psychosomatic Medicine. 73, 9, p. 737-742 < .001; coming for a manual social class background, β = .08, p = .001. The complete model explained 27% of the variance in 12-year resting SBP. In the analogous model for DBP, DBP reactivity was not a statistically significant predictor of 12-year resting DBP, β = .05, p = .06, ∆R2 = .003. Finally, since it has been argued that aerobic fitness and/or physical activity may be a serious confounder in studies such as this (35), we tested a final model which in addition to the covariates above we also adjusted for leisure physical activity, determined as whether participants engaged in five moderate or three strenuous bouts of exercise per week. SBP reactivity continued to predict resting SBP 12 years later, β = .08, p = .004, ∆R2 = .006. Effects of sex, age, and socioeconomic position on the prediction of 12-year followup SBP Similar multiple linear regression analyses were undertaken separately for men and women, the three age cohorts, and the two socioeconomic position groups. SBP reactivity was positively associated with subsequent resting SBP for both men, β = .10, p = .01, ∆R2 = .010, and women, β = .12, p = .002, ∆R2 = .011, and for manual, β = .11, p = .004, ∆R2 = .011, and non-manual, β = .10, p = .007, ∆R2 = .009, social class groups. SBP reactivity significantly predicted 12-year resting SBP levels in the youngest cohort, β = .14, p = .001, ∆R2 = .017, the middle cohort, β = .09, p = .04, ∆R2 = .008, but not the oldest cohort, β = .12, p = .06, ∆R2 = .013. There was no significant interaction effect on cohort × SBP reactivity on follow-up resting SBP. Reactivity and the 12-year upward drift in blood pressure 12 Pre-print. Cite as Blood Pressure Reactions to Acute Mental Stress and Future Blood Pressure Status: Data From the 12-Year FollowUp of the West of Scotland Study Carroll, D., Phillips, A., Der, G., Hunt, K. & Benzeval, M. 1 Nov 2011 In : Psychosomatic Medicine. 73, 9, p. 737-742 SBP reactivity was positively correlated with the upward drift in SBP resting levels during the 12 years since baseline, r (1194) = .22, p < .001; DBP reactivity was positively correlated with upward drift in resting DBP, r (1194) = .23, p <.001. The same multivariate regression models as those above were then tested. SBP reactivity continued to predict SBP upward drift, β = .10, p < .001, ∆R2 = .009. However, for DBP reactivity, the prediction of DBP upward drift was no longer statistically significant, β = .05, p = .06, ∆R2 = .003. In a final model, which in addition to the covariates above also adjusted for leisure physical activity, SBP reactivity continued to predict SBP drift, β = .08, p = .02, ∆R2 = .005. Again, it is important to note here that leisure physical activity data were only available for the two older cohorts. Effects of sex, age, and socioeconomic position on the prediction of SBP upward drift As with absolute 12-year follow-up SBP levels, the multivariate regression models were tested separately for men and women, the three age cohorts, and the two socioeconomic position groups. The outcomes were virtually identical to those reported above for absolute level. SBP reactivity predicted subsequent resting SBP for both men, β = .09, p = .01, ∆R2 = .008, and women, β = .11, p = .002, ∆R2 = .011, and for manual, β = .11, p = .004, ∆R2 = .011, and non-manual, β = .10, p = .007, ∆R2 = .008, socioeconomic status groups. As before, SBP reactivity was a stronger predictor of SBP upward drift in the youngest cohort, β = .14, p = .001, ∆R2 = .018, than in the middle, β = .09, p = .04, ∆R2 = .007, and older, β = .11, p = .06, ∆R2 = .010, cohorts. Again, however, 13 Pre-print. Cite as Blood Pressure Reactions to Acute Mental Stress and Future Blood Pressure Status: Data From the 12-Year FollowUp of the West of Scotland Study Carroll, D., Phillips, A., Der, G., Hunt, K. & Benzeval, M. 1 Nov 2011 In : Psychosomatic Medicine. 73, 9, p. 737-742 there was no significant interaction effect of cohort × SBP reactivity on SBP upward drift. Reactivity and hypertension Five hundred and seventy-five (48%) participants met the criteria for hypertension at the 12-year follow-up. In an unadjusted model, SBP reactivity positively predicted risk for hypertension, OR = 1.01, 95%CI 1.00 – 1.02, p < .03. In the model adjusting for the same covariates that we adjusted for in linear regression above, SBP reactivity continued to predict the 12-year risk for hypertension, OR = 1.03, 95%CI 1.01 – 1.04, p < .001; if anything the association between SBP reactivity and future hypertension was stronger in the multivariate model. As illustration, we plot per cent of participants with hypertension for tertiles of SBP reactivity in Figure 1. Tertiles were formed from the raw, unadjusted, SBP reactivity values. DBP reactivity did not significantly predict hypertension. We also examined new incident hypertension by removing participants who were hypertensive at baseline. In this analysis, antihypertensive medication status at baseline was no longer used as a covariate. In this new fully adjusted model, SBP reactivity continued to predict hypertension 12 years later, OR = 1.03, 95%CI 1.01 – 1.04, p = .001. Analogously, we also examined the association between SBP reactivity and later onset hypertension by removing participants who were hypertension at the earlier 5-year follow up. Again, SBP reactivity predicted hypertension at 12 years, OR = 1.03, 95%CI 1.01 – 1.04, p <.001 Finally, as sensitivity analyses, we re-run the original fully adjusted model defining hypertension solely in terms of the blood pressure criteria in one case and solely in terms of self-reported antihypertensive medication in the other case. Thirty eight per 14 Pre-print. Cite as Blood Pressure Reactions to Acute Mental Stress and Future Blood Pressure Status: Data From the 12-Year FollowUp of the West of Scotland Study Carroll, D., Phillips, A., Der, G., Hunt, K. & Benzeval, M. 1 Nov 2011 In : Psychosomatic Medicine. 73, 9, p. 737-742 cent of participants were categorized as hypertensive using the former criterion and 22% using the latter criterion. In both instances, SBP reactivity predicted future hypertension, OR = 1.02, 95%CI 1.00 – 1.03, p = .007 and OR = 1.02, 95%CI 1.01 – 1.04, p = .003, respectively. [Insert Figure 1 about here] DISCUSSION There was a positive bivariate relationship between the magnitude of SBP reactions to a mental stress exposure and resting SBP 12 years later. This association was still evident following adjustment for a range of potential confounding variables, such as age, sex, socioeconomic status, body mass index, performance score on the stress task, and resting blood pressure at the earlier time point. No analogous association emerged for DBP from bivariate and multivariate analyses. As such, our findings closely replicate those we reported previously from the 5-year follow-up (8). In addition, SBP reactivity was also positively associated in both bivariate and multivariate analyses with the upward drift in resting SBP over the 12 years between follow-ups. Although there was a bivariate relationship between DBP reactivity and the 12-year change in resting DBP, the association was no longer significant after adjustment for covariates in multivariate analysis. With the exception of this last result, our findings replicate those reported from the 5-year follow-up (8). Overall, though, the observed effect sizes were small with SBP reactivity accounting for only 1% of the variance in resting SBP 12 years later and in SBP upward drift, as compared to 2% and over 3% respectively in the 5-year follow-up. Nevertheless, the present effect sizes are exactly in line with the aggregate effect size in a 15 Pre-print. Cite as Blood Pressure Reactions to Acute Mental Stress and Future Blood Pressure Status: Data From the 12-Year FollowUp of the West of Scotland Study Carroll, D., Phillips, A., Der, G., Hunt, K. & Benzeval, M. 1 Nov 2011 In : Psychosomatic Medicine. 73, 9, p. 737-742 recent meta-analysis of reactivity and cardiovascular disease outcomes (26). Further, in the present multivariate regressions we adjusted for substantially more covariates than in the 5-year follow-up analyses. However, in models that adjusted only for age, body mass index, and initial resting blood pressure, the outcomes were very much the same as those reported above with SBP reactivity accounting for just over 1% of the variance in 12-year resting SBP and SBP upward drift. Thus, it would appear that the associations between reactivity and the blood pressure outcomes are simply weaker at the more distal followup. Not only did SBP reactivity predict future resting SBP and the 12-year upward drift in SBP, it also predicted future hypertension status. Those with higher SBP reactivity were more likely to meet the criteria for hypertension 12 years later; no analogous association was evident for DBP reactivity. The subgroup analyses indicated effects of much the same order for men and women and participants from manual and non-manual socioeconomic groups. It has been argued that the most consistent and robust associations between reactivity and future blood pressure status emerge from studies with younger samples and that a preponderance of older participants in some prospective studies may be responsible for the modest effects seen (27). As indicated, the present study, by virtue of the three narrow age cohorts recruited, was perhaps uniquely placed to examine age variations in the predictive power of reactivity on future blood pressure status. However, the age cohort × SBP reactivity interaction effects on the SBP outcomes were not statistically significant, indicating that age did not moderate the association between SBP reactivity and future blood pressure status. 16 Pre-print. Cite as Blood Pressure Reactions to Acute Mental Stress and Future Blood Pressure Status: Data From the 12-Year FollowUp of the West of Scotland Study Carroll, D., Phillips, A., Der, G., Hunt, K. & Benzeval, M. 1 Nov 2011 In : Psychosomatic Medicine. 73, 9, p. 737-742 It is worth noting that the upward drift in resting blood pressure over the 12 years of the study was noticeably modest. As we speculated previously, this could reflect the possibility that participants with higher initial resting blood pressures could be receiving antihypertensive medication by the later follow-up, and as a consequence would have registered smaller upward drifts in blood pressure (7). Compared to 8% at baseline, when stress testing was undertaken, 21% reported taking antihypertensive medication at the fifth and final follow-up and when these participants were removed larger mean upward drifts were observed, mean = 7.12 (SD = 20.04) mmHg and mean = 3.20 (SD = 12.10) mmHg for SBP and DBP drift respectively. Further, with these participants removed, the associations between SBP reactivity and the SBP outcomes in the multivariate analyses were somewhat stronger, β = .14, p < .001, ∆R2 = .017 and β = .15, p < .001, ∆R2 = .020 for 12-year resting SBP and SBP upward drift respectively. This would suggest that antihypertensive medication is not only masking upward blood pressure drift over time, it is also somewhat attenuating the association between reactivity and future blood pressure status. In addition, given that participants in the youngest cohort were less likely to be taking antihypertensive medication, 3% as opposed to 22% and 52% in the middle and oldest cohort respectively, this attenuation effect of medication on the link between reactivity and future blood pressure could account for why we tended to see the strongest association in the youngest cohort. This study is not without its limitations. First, there was high variability in resting blood pressure, upward blood pressure drift, and reactivity. However, given the standardized procedures for measuring blood pressure, this is unlikely to reflect measurement error. In addition, other epidemiological studies of the same magnitude, 17 Pre-print. Cite as Blood Pressure Reactions to Acute Mental Stress and Future Blood Pressure Status: Data From the 12-Year FollowUp of the West of Scotland Study Carroll, D., Phillips, A., Der, G., Hunt, K. & Benzeval, M. 1 Nov 2011 In : Psychosomatic Medicine. 73, 9, p. 737-742 such as Caerphilly (36) and Whitehall II (9, 10), reports similar SDs for blood pressure. Second, determining causality from even prospective observational studies is fraught with pitfalls (37). However, in the present analyses we adjusted for a broad range of potential confounders, more than most previous studies (26). Nevertheless, residual confounding as a consequence of poorly measured or unmeasured variables cannot be wholly discounted. In addition, prospective observational analyses cannot distinguish with certainty between prodromal markers of disease and factors that play a causal pathophysiological role. Third, 451 (27%) of the participants who were stress tested at baseline were unavailable for assessment 12 years later. For 137, this was because they had died or were incapacitated in the interim. However, SBP reactivity did not differ between those who remained in the study and those who did not: 11.5 and 11.3 mmHg, respectively. Fourth, the baseline and task durations in the present study were relatively short, and the number of blood pressure readings were small in comparison to other studies. However, it is likely that, given these limitations, the effect sizes observed in this study underestimate the true predictive value of reactivity. In conclusion, greater SBP reactions to acute psychological stress were associated with resting SBP 12 years later, more upward drift in SBP levels over time, and a greater likelihood of suffering from hypertension at the 12-year follow-up. These associations withstood adjustment for a range of covariates. Although the effect sizes for SBP reactivity were weaker than those found at a 5-year follow-up in this study (8), they were the same order of magnitude as those observed for body mass index. The analogous associations for DBP reactivity were not statistically significant in multivariate analyses. There was some indication that antihypertensive medication tended to attenuate the 18 Pre-print. Cite as Blood Pressure Reactions to Acute Mental Stress and Future Blood Pressure Status: Data From the 12-Year FollowUp of the West of Scotland Study Carroll, D., Phillips, A., Der, G., Hunt, K. & Benzeval, M. 1 Nov 2011 In : Psychosomatic Medicine. 73, 9, p. 737-742 relationship between SBP reactivity and the SBP outcomes. Overall, our findings lend support to the original reactivity hypothesis. 19 Pre-print. Cite as Blood Pressure Reactions to Acute Mental Stress and Future Blood Pressure Status: Data From the 12-Year FollowUp of the West of Scotland Study Carroll, D., Phillips, A., Der, G., Hunt, K. & Benzeval, M. 1 Nov 2011 In : Psychosomatic Medicine. 73, 9, p. 737-742 Acknowledgements The West of Scotland Twenty-07 Study is funded by the UK Medical Research Council and the data were originally collected by the MRC Social and Public Health Sciences Unit. We are grateful to all of the participants in the Study, and to the survey staff and research nurses who carried it out. The data are employed here with the permission of the Twenty-07 Steering Group (Project No. EC201003). GD, KH, and MP are funded by the Medical Research Council. 20 Pre-print. Cite as Blood Pressure Reactions to Acute Mental Stress and Future Blood Pressure Status: Data From the 12-Year FollowUp of the West of Scotland Study Carroll, D., Phillips, A., Der, G., Hunt, K. & Benzeval, M. 1 Nov 2011 In : Psychosomatic Medicine. 73, 9, p. 737-742 References 1. Turner JR. Cardiovascular reactivity and stress. New York: Plenum Press; 1994. 2. Wright RA, Gendolla GHE, Eds. How motivation affects cardiovascular response: Mechanisms and applications. Washington D.C.: APA Press; 2011. 3. Obrist P. Cardiovascular Psychophysiology: A perspective. New York: Plenum Press; 1981. 4. Light KC. Cardiovascular responses to effortful active coping: implications for the role of stress in hypertension development. Psychophysiology. 1981;18:216-25. 5. Manuck SB, Kasprowicz AL, Muldoon MF. Behaviourally evoked cardiovascular reactivity and hypertension: conceptual issues and potential associations. Annals Behav Med. 1990;12:17-29. 6. Carroll D, Phillips AC, Balanos GM. Metabolically-exaggerated cardiac reactions to acute psychological stress revisited. Psychophysiology. 2009;46:270-5. 7. Schwartz AR, Gerin W, Davidson, KW, Pickering TG, Brosschot JF, Thayer JF, Christenfeld N, Linden W. Toward a causal disease model of cardiovascular responses to stress and the development of cardiovascular disease. Psychosom Med. 2003;65: 22-35. 8. Carroll D, Ring C, Hunt K, Ford G, Macintyre S. Blood pressure reactions to stress and the prediction of future blood pressure: effects of sex, age, and socioeconomic position. Psychosom Med. 2003;65:1058-64. 9. Carroll D, Smith GD, Sheffield D, Shipley MJ, Marmot MG. Pressor reactions to psychological stress and prediction of future blood pressure: data from the Whitehall II Study. BMJ. 1995;310:771-6. 10. Carroll D, Smith GD, Shipley MJ, Steptoe A, Brunner EJ, Marmot MG. Blood pressure reactions to acute psychological stress and future blood pressure status: a 10year follow-up of men in the Whitehall II study. Psychosom Med. 2001;63:737-43. 11. Everson SA, Kaplan GA, Goldberg DE, Salonen JT. Anticipatory blood pressure response to exercise predicts future high blood pressure in middle-aged men. Hypertension. 1996;27:1059-64. 12. Newman JD, McGarvey ST, Steele MS. Longitudinal association of cardiovascular reactivity and blood pressure in Samoan adolescents. Psychosom Med. 1999;61:243-9. 13. Matthews KA, Woodall KL, Allen MT. Cardiovascular reactivity to stress predicts future blood pressure status. Hypertension. 1993;22:479-85. 14. Markovitz JH, Raczynski JM, Wallace D, Chettur V, Chesney MA. Cardiovascular reactivity to video game predicts subsequent blood pressure increases in young men: The CARDIA study. Psychosom Med. 1998;60:186-91. 15. Treiber FA, Turner JR, Davis H, Strong WB. Prediction of resting cardiovascular functioning in youth with family histories of essential hypertension: a 5-year follow-up. Int J Behav Med. 1997;4:278-91 21 Pre-print. Cite as Blood Pressure Reactions to Acute Mental Stress and Future Blood Pressure Status: Data From the 12-Year FollowUp of the West of Scotland Study Carroll, D., Phillips, A., Der, G., Hunt, K. & Benzeval, M. 1 Nov 2011 In : Psychosomatic Medicine. 73, 9, p. 737-742 16. Flaa A, Eide IK, Kjeldsen SE, Rostrup M. Sympathoadrenal stress reactivity is a predictor of future blood pressure: an 18-year follow-up study. Hypertension. 2008;52:336-41. 17. Light KC, Dolan CA, Davis MR, Sherwood A. Cardiovascular responses to an active coping challenge as predictors of blood pressure patterns 10 to 15 years later. Psychosom Med. 1992;54:217-30. 18. Tuomisto MT, Majahalme S, Kahonen M, Fredrikson M, Turjanmaa V. Psychological stress tasks in the prediction of blood pressure level and need for antihypertensive medication: 9-12 years of follow-up. Health Psychol. 2005;24:77-87. 19. Barnett PA, Spence JD, Manuck SB, Jennings JR. Psychological stress and the progression of carotid artery disease. J Hypertens. 1997;15:49-55. 20. Matthews KA, Owens JF, Kuller LH, Sutton-Tyrrell K, Lassila HC, Wolfson SK. Stress-induced pulse pressure change predicts women's carotid atherosclerosis. Stroke. 1998;29:1525-30. 21. Everson SA, Lynch JW, Chesney MA, Kaplan GA, Goldberg DE, Shade SB, Cohen RD, Salonen R, Salonen JT. Interaction of workplace demands and cardiovascular reactivity in progression of carotid atherosclerosis: population based study. BMJ. 1997;314:553-8. 22. Lynch JW, Everson SA, Kaplan GA, Salonen R, Salonen JT. Does low socioeconomic status potentiate the effects of heightened cardiovascular responses to stress on the progression of carotid atherosclerosis? Am J Pub Health. 1998;88:389-94. 23. Georgiades A, Lemne C, de Faire U, Lindvall K, Fredrikson M. Stress-induced blood pressure measurements predict left ventricular mass over three years among borderline hypertensive men. European J Clin Invest. 1997;27:733-9. 24. Kapuku GK, Treiber FA, Davis HC, Harshfield GA, Cook BB, Mensah GA. Hemodynamic function at rest, during acute stress, and in the field: predictors of cardiac structure and function 2 years later in youth. Hypertension. 1999;34:1026-31. 25. Murdison KA, Treiber FA, Mensah G, Davis H, Thompson W, Strong WB. Prediction of left ventricular mass in youth with family histories of essential hypertension. Am J Med Sci. 1998;315:118-23. 26. Chida Y, Steptoe A. Greater cardiovascular responses to laboratory mental stress are associated with poor subsequent cardiovascular risk status: a meta-analysis of prospective evidence. Hypertension. 2010;55:1026-32. 27. Treiber FA, Kamarck T, Schneiderman N, Sheffield D, Kapuku G, Taylor T. Cardiovascular reactivity and development of preclinical and clinical disease states. Psychosomatic medicine. 2003;65:46-62. 28. Ford G, Ecob R, Hunt K, Macintyre S, West P. Patterns of class inequality in health through the lifespan: class gradients at 15, 35 and 55 years in the west of Scotland. Soc Sci Med. 1994;39:1037-50. 29. Carroll D, Phillips AC, Der G. Body mass index, abdominal adiposity, obesity and cardiovascular reactions to psychological stress in a large community sample. Psychosom Med. 2008;70:653-60. 30. Registrar General. Classification of Occupations. London: HMSO, 1980. 31. Ring C, Burns VE, Carroll D. Shifting hemodynamics of blood pressure control during prolonged mental stress. Psychophysiology. 2002;39:585-90. 22 Pre-print. Cite as Blood Pressure Reactions to Acute Mental Stress and Future Blood Pressure Status: Data From the 12-Year FollowUp of the West of Scotland Study Carroll, D., Phillips, A., Der, G., Hunt, K. & Benzeval, M. 1 Nov 2011 In : Psychosomatic Medicine. 73, 9, p. 737-742 32. Winzer A, Ring C, Carroll D, Willemsen G, Drayson M, Kendall M. Secretory immunoglobulin A and cardiovascular reactions to mental arithmetic, cold pressor, and exercise: effects of beta-adrenergic blockade. Psychophysiology. 1999;36:591-601. 33. Willemsen G, Ring C, Carroll D, Evans P, Clow A, Hucklebridge F. Secretory immunoglobulin A and cardiovascular reactions to mental arithmetic and cold pressor. Psychophysiology. 1998;35:252-9. 34. O'Brien E, Waeber B, Parati G, Staessen J, Myers MG. Blood pressure measuring devices: recommendations of the European Society of Hypertension. BMJ 2001;322:5316. 35. Forcier K, Stroud LR, Papandonatos GD, Hitsman B, Reiches M, Krishnamoorty J, Naura R. Links between physical fitness and cardiovascular reactivity and recovery to psychological stressors: a meta-analysis. Health Psychol. 2006;25:723-39.. 36. Carroll D, Davey Smith G, Sheffield D, Willemsen G, Sweetnam PM, Gallacher JE, Elwood PC. Blood pressure reactions to the cold pressor test and the prediction of future blood pressure status: data from the Caerphilly study. J Human Hypertens. 1996;10:777-80. 37. Christenfeld NJ, Sloan RP, Carroll D, Greenland S. Risk factors, confounding, and the illusion of statistical control. Psychosom Med. 2004;66:868-75. 23 Pre-print. Cite as Blood Pressure Reactions to Acute Mental Stress and Future Blood Pressure Status: Data From the 12-Year FollowUp of the West of Scotland Study Carroll, D., Phillips, A., Der, G., Hunt, K. & Benzeval, M. 1 Nov 2011 In : Psychosomatic Medicine. 73, 9, p. 737-742 Table 1: Socio-demographics of the sample at baseline (N = 1647) Mean / N SD / % Age 42.2 15.45 Sex (male) 757 46 Non-manual occupation group 870 53 BMI 25.7 4.26 Current smokers 593 36 Current drinker 1497 91 Physical activity 300 18 PASAT performance score 43.8 9.20 Variable 24 Pre-print. Cite as Blood Pressure Reactions to Acute Mental Stress and Future Blood Pressure Status: Data From the 12-Year FollowUp of the West of Scotland Study Carroll, D., Phillips, A., Der, G., Hunt, K. & Benzeval, M. 1 Nov 2011 In : Psychosomatic Medicine. 73, 9, p. 737-742 Table 2. Mean (SD) of the key blood pressure variables (N = 1196) Variable SBP (mmHg) DBP (mmHg) Initial resting blood pressure 128.23 (20.26) 78.76 (11.71) Reactivity 11.54 (11.54) 6.87 (8.65) Final resting blood pressure at 12 years 132.34 (22.35) 79.60 (13.79) 25 Pre-print. Cite as Blood Pressure Reactions to Acute Mental Stress and Future Blood Pressure Status: Data From the 12-Year FollowUp of the West of Scotland Study Carroll, D., Phillips, A., Der, G., Hunt, K. & Benzeval, M. 1 Nov 2011 In : Psychosomatic Medicine. 73, 9, p. 737-742 Figure 1. Percentage meeting the criteria for hypertension by tertiles of SBP reactivity 26 Pre-print. Cite as Blood Pressure Reactions to Acute Mental Stress and Future Blood Pressure Status: Data From the 12-Year FollowUp of the West of Scotland Study Carroll, D., Phillips, A., Der, G., Hunt, K. & Benzeval, M. 1 Nov 2011 In : Psychosomatic Medicine. 73, 9, p. 737-742 27