Strategic Cultures of Transformative Organization:

advertisement

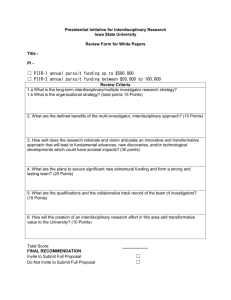

1 Strategic Cultures of Transformative Organization: The Coates of India Story1 Vipin Gupta Assistant Professor, Fordham University, New York, USA Kumkum Mukherjee Assistant Professor, Eastern Institute for Integrated Learning in Management, Calcutta, India Roma Puri Fellow, Eastern Institute for Integrated Learning in Management, Calcutta, India 1 We are thankful to the US National Science Foundation and Centre for New Economy and Culture in eGLOBE (EMPI Business School, Delhi), for funding the study as part of worldwide cross-cultural CEO research of Globe Research and Educational Foundation; and to Robert House, Principal Investigator, GLOBE Program, for allowing us to participate in the study. 2 Abstract In this chapter, recent developments in the transformative perspective are reviewed, with special reference to the concepts of change, leadership, and learning. The transformative perspective emphasizes how dynamic organizational learning can shape not just what the firm does, but also the meaning the firm associates with what it has been doing and its mission in the future. The transformative organizations gain a competitive advantage in a global milieu, as reflected in their high performance on multiple criteria, including profitability, agility, growth and reputation. In other words, transformative perspective allow the firms to transcend the paradox of performance, identified by Meyer & Gupta (1994), that an emphasis on some measures of performance makes the organizations simultaneously effective on those measures, and ineffective on other measures and thus subject to failure. A model of four strategic cultures is formulated, and the workings of the transformative organization are explicated using the story of Coates of India. 3 Introduction In recent years, transformative perspective has gained popularity among the social scientists, as is indicated by the concepts such as transformative change (Lichtenstein, 2000), transformative leadership (Astin & Astin, 2001; Bass, 1985; Bemis & Nanus, 1985), transformative mediation (Bush & Folger, 1994), transformative justice (Morris, 1994), transformative learning (Mezirow, 1991), transformative knowledge (Vargas, 1987), and transformative technology (Brent, 1991). Here we review the core insights of the transformative perspective with respect to change, leadership and learning. Then, we develop a theoretical model that highlights the importance of four domains – investor, competence, post-competence, and spiritual – in the strategic decision-making of the organizations. Our theoretical model builds on the GLOBE research (Gupta, Hanges & Dorfman, 2002) that highlights distinct sets of cultural values and practices in different regions of the world. We propose that the transformative organizations must deal with all these domains of strategic issues in their decision-making and learning process. The firms in different regions simplify the complexity of simultaneously managing multiple domains by prioritizing them from most important to least important, and then rewarding and legitimating firms based on the extent to which they adhere to the institutionalized expectations. Each firm is influenced by the institutional norms of the region for including the most important domains as critical element in its strategic decision-making, but at the same time enjoys substantial freedom of giving at least equivalent importance to the other domains. The processes of globalization and transnational investments make the need for excellence in all the domains particularly salient. The transformative perspective emphasizes how dynamic organizational learning can shape not just what the firm does, but also the meaning the firm associates with what it has been doing and its mission in the future. Such dynamic organizational learning is facilitated by a comparative understanding of the behaviors and values, generated through processes 4 such as perspective taking (Parker & Axtell, 2001) and relational capability (Dyer & Singh, 1998), which allows the firms to identify common patterns in apparently divergent behaviors. Through interactive learning, firms realize that the alternative strategic domains are also associated with high-performance, and so it is important to emphasize each, and not one over the others. The result is a change in the very system of organization, that encourages the firm to identify how devaluing some domains in the past limited its overall performance, and impeded development initiatives under conditions where the norms for the targeted domain were fulfilled. We identify the firms that demonstrate a focus on transformative perspective as the “transformative organizations”. We propose that the transformative organizations seek multifaceted competitive advantage in a global milieu, emphasizing multiple criteria, including profitability, agility, growth and reputation. In other words, transformative perspective helps the firms to transcend the paradox of performance, identified by Meyer & Gupta (1994), that an emphasis on some measures of performance makes the organizations simultaneously effective on those measures, and ineffective on other measures and thus subject to failure. The failure of Enron, whose policies were very effective in the investor domain, but not other domains, is a case in point. Next, we review the literature on transformative perspective, and present a theoretical model of strategic cultures of transformative organizations. Then, we explicate the theoretical model using the story of Coates of India. The story is based on the CEO interview and survey of the top management team conducted in 2001 as part of an international cross-cultural study. Review of the Transformative Perspective Below, we review transformative perspectives in three major domains: change, leadership, and learning. Transformative Perspective and Change 5 The transformative perspective fundamentally involves a transition in the forming process, from one focused on incremental change to that catalyst oriented towards quantum change. The emphasis is not on accelerating the incremental change, or bypassing certain steps of incremental change, but to generate a qualitatively different approach on how the change is evaluated and managed. In general, change happens when there is some variance, either in what the firm does and what it is expected to do (practices and norms to be met), or it what it does and what it expects to do (practices and values to be fulfilled). Once the change is ‘formed’, the firm seeks to benefit from its learning by institutionalizing the change intervention in all relevant aspects of its functioning. It may also diffuse the change among its external constituencies, and seek financial or non-financial benefits from such knowledge spillovers. This institutionalization and diffusion reflects ‘norming’ of the change. As the norms mature, including through reverse learning from the outcomes of other internal applications and of the use by the external constituencies, the change initiative is fulfilled, and the changed behavior becomes routinized for effortless enactment. However, the outcome of the changed behavior may not be the same in all cases. The more systematic and sustained the institutionalization and diffusion process, the greater the possibility of learning about its shortcomings. When the shortcomings are diagnosed and validated, the firm seeks to develop corrective interventions, and again goes through the forming, norming, and fulfilling phases, as shown in Figure 1. Insert Figure 1 About Here Thus, typically, the organizations go through a sequential process of change. In this process, they (1) may deny the need for change (Change by denial), (2) may become aware of the need for change, only after it has already happened gradually (Change by experience), (3) may mandate an instant change, as soon as they recognize and validate the need for change (Change by mandate), or (4) may reinterpret the pre-changed behavior in a way that the need 6 as well as direction for change becomes self-evident (Change by reinterpretation). In our view, the transformative change reflects a continuous openness to the change by reinterpretation, and a systematic approach to change by mandate and change by experience, so that the need for change is not denied. One may relate the four processes of change to Ferguson’s (1980) types of change. These types include: (1) Change by exception: the firms allow exceptions to their beliefs but do not change these beliefs. For example, when they encounter a case that does not fit their mental models, they classify them as being an exception to the rule (e.g. a profitable e-firm at the height of internet revolution). (2) Incremental change: a collection of small changes eventually alters, rather unconsciously, the mental model of the firm (e.g. failure of several unprofitable e-firms, along with reduced e-funding before the burst of internet bubble). (3) Pendulum change: an extreme point of view is exchanged for its opposite, and past is completely discredited as irrelevant or mistaken (e.g. a unprofitable e-firm that suddenly mandates profit as its Number 1 goal after the burst of internet bubble, and divests most of its businesses as not expected to be profitable). (4) Paradigm change: the firm steps out of the box for a more fundamental rethinking of premises, based on the integration of available information (e.g. a initially unprofitable e-firm that is able to stick to its fundamentally viable business plan, by improving its learning about new project management). In short, from a change perspective, transformative organizations recognize not only the reality of the changing world and of the accelerating pace of change, but also of the changing nature of change. Consequently, they do not seek to be effective in only some parts of a system, but seek proficiency in managing the multifaceted dimensions of their operation. Transformative Perspective and Leadership The transformational theory of leadership focuses on the ability of the leaders to motivate others to do more than they originally expected to do (Bass, 1985). The 7 transformational leaders shape and elevate the motives and goals of followers, thereby achieving significant change reflecting the community of interests of both leaders and followers, and freeing up the collective energies in pursuit of a common goal. The thrust is on creating institutions that motivate employees to recognize the community of their needs, and to empower them to satisfy these collective needs (Bemis & Nanus, 1985). The transformative perspective further integrates the collective organizational needs with an enhanced understanding of the potentiality of each member, and a wholesome conception of self in the personal, relational, societal, and communal domains. By recognizing that each employee is more than just an individual or a member of the organization, and has societal and communal identities also, the transformative leaders facilitate more of what each employee truly wants to accomplish without necessarily sacrificing the realization of collective needs. The employees also discover that their life in the organization need not be disjointed from their lives in the society and the community, and that the former can be lived in a way which serves their purpose and enhances their prestige in the society and the community also. As a result, transformative leadership becomes a reciprocal process whereby both leaders and followers raise one another to higher levels of motivation and morality. In this sense, transformative leadership builds on the values-based approaches to transformational leadership (Kuczmarski & Kuczmarski, 1995; Goeglein & Indvik, 2000). Further, Gandhi’s concept of trusteeship, which recognizes service as the purpose of leadership; moral principles as the basis of goals, decisions, and strategies; and employing a single standard of conduct in both public and private life; is crucial to the transformative leadership (Gupta et. al., 2002). In contrast to the transformational leadership, which focuses on enhancing efficiency and effectiveness through first-order quantitative change in motivation, the transformative leadership emphasizes a higher-order qualitative integration of 8 motivation over multiple domains. Consequently, transformative leadership generates changes in basic assumptions and goals of life, so that accomplishments in each domain are reinterpreted as being related to other domains, and thus serves higher-order purposes of life. Despite some similarities, the transformative leadership can also be distinguished from the transactional, transformational, and values-based transformational models of leadership. In the transactional model, the roles of each individual are clearly defined, and the responsibilities and expectations are limited and predictable. In contrast to the view of a transactional leader who must get things done, whether by focusing on the task or on the person, the transformative leader emphasizes the purpose, mission, and spirit of the action, so that the quantum nature of its benefits become self-evident to all. While the transformational model allows the expectations to be challenged, and motivates the individuals to see themselves as a member of the group and to focus on the satisfaction of collective needs, the values-based transformational model emphasizes how certain values of the leader are fulfilling for the followers, and encourage them to seek their attainment. Both these approaches could result into unjust outcomes, for they may exclude the members who do not find the values of the leader as fulfilling. The transformative model, on the other hand, generates a new interpretation of the reality, where the previously marginalized members are also able to engage themselves in the task of learning, and where meaningful linkages can be constructed between these members and the dominant organizational values and social and communal institutions. This is made possible because of the common learning on part of both organization as well as the members that they are an important part of others’ life. In summary, from a leadership perspective, transformative organizations recognize not just the reality of changing roles and of the need to empower participants to effectively and rapidly perform these roles, but also the changing nature of the roles that the leadership should be focusing on if the participant lives as well as the organizational mission are to be fulfilled. 9 Transformative Perspective and Learning Transormative approaches to learning focus on how learners construe, validate, and reformulate the meaning of their experience. One of the most popular models of transformative learning is of Mezirow (1991). According to Mezirow (1991: 167), transformative learning involves ‘perspective transformation’, which "is the process of becoming critically aware of how and why our assumptions have come to constrain the way we perceive, understand, and feel about our world; changing these structures of habitual expectation to make possible a more inclusive, discriminating, and integrating perspective; and, finally, making choices or otherwise acting upon these new understandings" Mezirow distinguishes between meaning structures, which are frames of reference based on the totality of individuals' cultural and contextual experiences that influence how they behave and interpret events, and meaning schemes (specific beliefs, attitudes, and emotional reactions) that make up these meaning structures. The usual learning process, as an individual adds to and integrates ideas within an existing scheme, contributes to a routine change in meaning structures. However, transformative learning, involving change in meaning structures, results from an accumulation of transformations in meaning schemes over a period of time, or more often from a ‘disorientating dilemma’ triggered by a life crises or major life transition. In general, Mezirow identifies experience, critical reflection, and rational discourse as three major catalysts of transformative learning. Each of these can encourage a change in the people’s frame of reference through critical reflection of their assumptions and beliefs, and consciously bringing about new worldviews. Boyd & Myers (1988) offer an alternative approach, which recognizes transformative learning to be more of an intuitive, creative, emotional process. They use the term transformative education to connote a fundamental change in one's personality involving both the resolution of a personal dilemma as well as the expansion of consciousness resulting in 10 greater personality integration. Transformative education draws on the "realm of interior experience, one constituent being the rational expressed through insights, judgments, and decision; the other being the extrarational expressed through symbols, images, and feelings" (Boyd & Myers, 1988: 275). It builds on the process of discernment, i.e. creating a personal vision or meaning of being a human. The discernment involves receptivity, recognition, and grieving. First, an individual shows receptivity to "alternative expressions of meaning," then recognizes that the message is authentic, and finally realizes that old patterns or ways of perceiving are no longer relevant, moves to adopt or establish new ways, and to integrate the old with the new patterns. Bush & Folger (1994) apply the transformative perspective to Alternative Dispute Resolution (ADR). They suggest a shift from a problem solving or settlement-oriented mediation that focuses on finding a mutually agreeable settlement of an immediate dispute, to ‘transformative mediation’ that seeks to transform the disputing parties by empowering them to understand their own situation and needs, as well as enabling them to recognize the situation and needs of their opponents. At the organizational level, transformative mediation may transform the representatives, but could leave out the constituencies, and engender a ‘scale up problem’ (Burgess & Burgess, 1996). Lederach (1989) emphasizes a more inclusive concept of “conflict transformation” which entails development of not just empowerment and mutual recognition, but also interdependence, justice, forgiveness, and reconciliation. The thrust is on creating dialogues in which people are empowered to express their needs and explore their differences, so that inclusion and participation is encouraged. Similarly, Montville (1993) underlines how dialogue helps people confirm each others' humanity and recognize beliefs and values of the other person, and the importance of historical analysis, including sharing of grievances and their recognition by the opponents, for encouraging transformation in the parties' relationships. 11 In essence, from a learning perspective, transformative organizations recognize not only the differences in perspectives and the need to empower participants to advocate their unique perspectives, but also the need to transform each individual’s meaning associated with these perspectives so that a more inclusive perspective is developed. Summary: There are significant similarities in the transformative approaches used in change, leadership, and learning domains. Each emphasizes the importance of recognizing differences and the need for change, empowering participants to share these differences and to bring about the change, and finally developing an integrative perspective relating these differences and changes to the very purpose of human and organizational life across multiple domains. As a result, the differences and changes are not seen as threatening or exceptions, and are instead sought for improving multiple dimensions of organizational and participant life. Consequently, the target of transformative approaches is not the actions of the organization, but the very culture of the organization. It is the emic aspect of the culture – the meaning the participant attach to the actions, that is more relevant for transformative approaches, than the etic aspect – the cross-culturally comparable actions and behaviours. Theoretical Model Using a transformative lens, we develop a theoretical model of the importance placed by the firms on alternative strategic values. We identify four types of strategic cultures, each typical of a distinct region of the world, and each reflecting an alternative domain of strategic values and associated change, leadership, and learning. The four strategic culture types are: (1) Investor Orientation, (2) Competence Orientation, (3) Post-competence Orientation, and (4) Spiritual Orientation. The first type is typical of the Western Hemisphere, the second of the Asia-Pacific, the third of the Europe, and the fourth of Africa. The key characteristics of each of these types are summarized below. 12 1) The first strategic culture type is Investor Orientation. It reflects paramount importance of cost control, sales volume, product quality and firm profitability in strategic decision-making. A focus on firm profitability, along with the significance of cost, sales and quality variables that have a direct impact on this profitability, indicates a strong investor culture where the emphasis is constantly on business unit and corporate performance. Investor culture is typical of the Western Hemisphere and Anglo societies, where the foremost responsibility of the business is towards its owners. Such cultures support autonomous organizational learning oriented towards tapping of well-defined business opportunities and resolution of anticipated and experienced business threats. The investor-oriented firms invest into multiple learning trajectories, each oriented towards a distinct business opportunity, and seek flexibility of shifting resources from one trajectory to another depending on the changing environmental context and the expected jackpot from the chosen trajectories. The change typically occurs through exception, recognizing that the same jackpot can not be shared by all firms; and the leadership is transactional in nature – oriented towards realization of the expected jackpot. 2) The second strategic culture type is Competence Orientation. It signifies a decisionmaking value where most emphasis is put on long-term competitive ability of the organization, along with the relational issues with those directly involved in the business operations. The thrust is mostly on cultivating and sustaining relationships with key business partners such as suppliers, alliances, and government agencies, customer satisfaction, employee professional growth and development, and employee relations issues such as employee well-being, safety and working conditions. Competence culture is typical of the Asia-Pacific societies, where the relationships and long-term competitive ability are most critical. Such cultures support collaborative organizational learning, but limit the flexibility of the firms in seeking new know-how. This is so because the benefits of know-how generally are diffused quite quickly throughout the relational network. On the other hand, the firms 13 incur the costs of know-how discovery and its codification on their own, and thereby seek to stand out from the rest and be recognized for their pioneering contributions. The change typically occurs through experience, based on accumulated learning of self and the partners; and the leadership is transformational in nature identifying community of group interest. 3) The third strategic culture type is Post-competence Orientation. It signifies a strategic perspective that puts most priority on societal welfare, including environmental concerns, welfare of local community, nation’s economic welfare, minority employees, and employee gender. Post-competence culture is typical of the European societies. Such cultures support socialist organizational learning, where the non-business partners such as the special interest groups, social activists, and community leaders play an important role in the corporate decision-making. The primarily responsibility of the firms is not to their investors or their business partners, but to respect collective interest of the members of the community in ecology and welfare issues. The post-competence oriented firms are most willing to assume the costs of social charter, and to believe that the social charter is not necessarily at odds with the investor and business relationship concerns. Such firms develop competence in specific areas of social charter through targeted interventions, such as environment-friendly machinery and products, which are supported by the institutionalized laws at the national level. These firms are valued as responsible corporate citizens and enjoy high stock valuation as rewards to their investors and that brings prestige and similarly high valuation for the business partners. The change tends to occur through mandate, where specific interventions are legitimated; and values-based transformation is emphasized for supporting the participant initiatives towards these interventions. 4) The final strategic culture type is Spiritual Orientation. It reflects a strategic preference for ethical considerations, and being devoted to the super-natural forces, such as auspicious days, forecasts by truth sayers, and pleasing, respecting, not offending a divine being. Spiritual 14 culture is typical of the firms in Africa. Such cultures support communal organizational learning, where the self-identity of the firms is defined in terms of the membership of a specific community of beliefs. Each community of belief, religious or otherwise, expect certain forms of role performance from its members, including holding to certain beliefs about a deity, engaging in ritual behaviors, and using certain spiritual, cognitive and emotional criteria about morality. Glock and Stark (1965) have identified five manifestations of spiritual orientation. These include: (1) an experiential manifestation, capturing normative religious experiences; (2) a belief manifestation, capturing normative religious beliefs, (3) a ritual manifestation, capturing normative religious practices, (4) an intellectual manifestation, capturing knowledge about these religious norms, and (5) a devotional manifestation, capturing enacted religious practices and attitudes. The spiritually oriented firms are highly concerned about the kind of people they deal with. To them, it is difficult to separate the identity of the firm from that of the others the firm interacts with. The key implication is the importance of the relationship with and recognition by others, since the key organizing principle is “ubuntu” or that a person is a person through others. Ubuntu refers to “humaneness – a pervasive spirit of caring and community, harmony and hospitality, respect and responsiveness – that individuals and groups display for one another.” (Mangaliso, 2001: 24). In Africa, ubuntu is invariably invoked as a scale for weighing good versus bad, right versus wrong, just versus unjust, while interpreting critical issues and solving problems. The change is based on self-interpretation process, involving assessment of its humaneness; and the transformative leadership is favored to facilitate an integrative interpretation. Strategic Types and Cultural Salience: While the four strategic types typify the strategic cultures of firms in distinct regions, each is also characteristic of the firms in any given region. Since each region is multifaceted, each firm’s culture puts at least some strategic significance to issues identifiable with more than one type. The cultural orientation of the 15 firms can be ordered in a salience space indicating the significance of each particular cultural type in their strategic values. The salience space has an influence on not just the firm’s behavior, but also of the behavior of the members. At the individual level, salience indicates “the degree to which the person’s relationships to specified set of others depends on his or her being a particular kind of person, i.e. occupying a particular position in an organized structure of relationships and playing a particular role.” (Stryker & Serpe, 1982: 207). At any level, Cultural Salience can be measured using comparative scores on the four types of strategic cultures. The more salient a strategic culture type, the more likely the firms would activate it in their strategic decision making, and the more likely its organizational learning would be dominated by the issues critical to that type. On the other hand, the more transformative an organization is, the more likely it would be responsive to the issues related to other types also. Next we discuss the research methodology used to test the relevance of the theoretical model, for validating the force of Cultural Salience, and for investigating the development of a transformative organization that recognizes the integrative importance of the four domains. Research Methodology For our study, we chose to study an Indian firm, whose ownership has transferred from a British parent, to first a French parent, and then to Dutch/Japanese parent, over the last ten years. The firm was studied using the CEO interview guide and top management team survey of the Global Leadership and Organizational Behavior Effectiveness (GLOBE) program. GLOBE program developed these research instruments for study of CEOs and top management teams in more than 30 nations of the world, under the overall coordination of Professor Robert House at the Wharton School. In India, the study is being conducted in 30 states, with a sample of 40 firms in each state, under the overall coordination of the first author. The top management team surveys included questions relating to the leadership of the CEO. In addition, there were 17 questions intended to learn about the strategic values, where 16 the respondents were asked how much importance “should be” assigned to each factor when making critical management decisions. These 17 value items were used to construct four types of strategic culture scales. The item composition of the four scales is given in Table 1. A scale validation analysis of 212 firms from 7 states in Northeast India showed that the four scales were internally consistent (Cronbach alpha>0.70), both at the firm level as well as the top management level. --------------------------------Insert Table 1 About Here --------------------------------The interview guide asked the CEOs about their background, leadership goals, management philosophy, and personal strengths and weaknesses. These items were supplemented withquestions about the industrial relations climate in the main plant of the firm in India, located in the same city where the firm had its domestic headquarters. More details about the firm (Coates of India) are given in the next section to set the research context. Research Context: Coates of India (COI) was set up in 1947 as a wholly owned subsidiary of Coates Brothers Plc, UK in the state of West Bengal in Calcutta, for manufacturing and marketing of printing inks and allied products used in the process of printing. The parent firm diluted its stake in COI to 66.2% in 1962. In 1991, French group TotalFina, a leading player in global crude and petroleum industry, took over the parent firm, and acquired a 51% stake in COI. In 1999, TotalFina sold its printing inks business worldwide to Sun Chemical group of the Netherlands, which is a wholly owned subsidiary of $10-billion Dainippon Inks and Chemicals (DIC) Group of Japan. DIC Group, besides being a global leader in graphic arts products, has a significant presence in printers' supplies, machinery, pigments and reprographic products. As part of the deal, the resins and industrial adhesives business of COI 17 were spun off to TotalFina, and the ownership of COI was transferred to DIC. DIC had been operating in India through marketing agents, and saw COI as a valuable opportunity for expanding further into India. It immediately sought to use the entire marketing network of COI, and increased its equity stake in COI to 59.4 per cent. The board of COI was restructured to bring in four Japanese directors to oversee the strategic growth. On December 31, 1997, COI had transferred its packaging coatings business to a separate 100% subsidiary Coates Coatings India Limited (CCIL). The goal was to bring in Valspar Corporation of the US as a joint venture partner for the packaging coatings business, and to divest that business in a phased manner totally to Valsper as the business develops through a capital infusion and new technology from the latter. In the meantime, there was a shift in packaging concept from metal containers to plastic poly-tubes in India, which led Valsper – whose interests lay principally in can packaging coatings market – to back out of the joint venture deal in 2001. In June 2001, COI/CCIL initiated an alternative agreement with the new group parent company DIC for perpetual transfer of printing inks technology. The printing ink industry essentially consists of pigments, resins, additives and solvents. Pigment is the main raw material for manufacturing inks, resins give special properties to the inks while additives are necessary for maintaining the flow. The principal users of printing inks are packaging, printing and publishing industries. In India, packaging market for fast moving consumer goods (FMCG) sector is a key segment, accounting for a share of 40 per cent. In addition, in November of 2001, a new $1.3 million plant was inaugurated in the state of Gujarat at Ahmedabad for the manufacture of newspaper blank with the technology support from DIC. DIC is currently looking to upgrade product mix of COI, which has a battery of seven manufacturing plants spread in all parts of India, at Calcutta, Mumbai, Ahmedabad, Delhi, 18 Chennai, Bangalore and Noida (New Delhi), and seven sales offices located in various metropolitan cities, deemed a key advantage in the applications-oriented printing ink industry. Globally, the US, Japan, and Germany account for two-thirds of the $15 billion sales of the printing ink industry. The US accounts for about 30 percent of the global market. Two firms hold a total of 80% market share in the US: Sun Chemicals and Flint Ink. These two firms have transformed the industry into a highly concentrated structure through a series of acquisitions of smaller ink manufacturers in the US and overseas. With diminished opportunities for growth through acquisitions, DIC is now looking for organic growth opportunities for its subsidiary. India represents a key emerging market for such organic growth. The Indian domestic ink market is valued at $125 million (Rs. 6 billion), with a production volume of 50,000 tons. It has seen 12-15% growth over the past few years, and is expected to sustain this growth rate in the near future. The market is divided equally between a concentrated organized sector, with a few medium-to-large scale firms, and a fragmented unorganized sector, with more than 200 small-scale ink manufactures. At the top are the two firms: COI and its principal competitor, Hindustan Inks & Raisins Ltd (HRIL). HRIL, set up in 1991, has been steadily gaining market share from COI, principally because of a 15-year sales tax exemption for its core plant at Daman, that has allowed it to become the first Indian firm to successfully backward integrate manufacture of two core ingredients of printing inks viz. resins and flushed pigments, and to set up new units including a wholly-owned subsidiary in Austria to facilitate exports. In response, COI has increasingly focused on the premium segment, realizing a greater price per kg of ink as compared to other players in the market. The strategy of COI is based on its strong brand equity, regional manufacturing plants and sales offices to cater to specific needs of different markets, and now on the technological and marketing support of the DIC 19 group. Its products are perceived to be high quality, backed by continuous research and development expenditures, and its technology state-of-the-art. It has been at the forefront of ongoing modernization of its plants through extensive capital investments, raising its installed capacities by 10-15 percent every year, and revamping the computer system and other balancing equipment in its factories to meet the higher demand for products, and has seen profitable growth despite a recent slowdown in the global and Indian packaging coatings market. In summary, Coates of India has been historically influenced by the culture of the Anglo parent, and later of the European parent, and more recently by the Japanese parent. Further, its presence in the State of West Bengal – which is known to have leftist/socialist leanings should also influence the strategic culture of Coates of India. It has strong brand and technological base that has enabled it to realize profitable growth, but does not necessarily have a significant competitive edge in costs over the new entrants. On the whole, the formative Anglo influences appear to support its Investor Orientation, while the recent Japanese influences appear to be dominant in a focus on Competence Orientation. The French influences appear to be relatively weak on the strategic culture of Coates of India, particularly because the core business of the ex-French parent was quite different from that of the Coates of India. Also, the Dutch influences are possibly dwarfed by the proactive role taken by the Japanese global parent company with respect to the Indian subsidiary. Still, the presence in the socialist state of West Bengal should have strengthened its Post-competence Orientation. Finally, since the firm is based in India, where the culture is relatively spiritual in nature, one would expect non-trivial significance of Spiritual Orientation in firm’s strategic culture. Next we confirm these expectations using the top management questionnaire survey. 20 Findings: Top Management Questionnaire Survey Table 2 gives the scores of the firm on the four Strategic Culture scales, both at the individual top management level as well as the aggregated firm level. --------------------------------Insert Table 2 About Here --------------------------------As can be seen, on a scale of 1 to 7, the firm scored 6.29 on Investor Orientation and 6.03 on Competence Orientation. The difference between these two types of strategic culture was not significant (difference = 0.26; df=5; p>0.05). Thus, the top management of the firm puts “very high” importance on both Investor Orientation and Competence Orientation. The Spearman’s rank correlation between the scores of top management on these two was 0.96 (p<0.01). Thus, the top managers who focused more on Investor Orientation emphasized more of Competence Orientation also. However, there was a greater variation in the individual top manager values for Investor Orientation (from 5.00 to 7.00), than for Competence Orientation (from 4.80 to 6.40). The firm’s score on Post-competence Orientation was 4.90, which was significantly different from its scores on Investor Orientation (difference = 1.39; df=5; p <0.05) and on Competence Orientation (difference =1.13; df=5; p<0.01). Further, the Spearman’s rank correlation of the top manager scores on Post-competence orientation was not significant with either Competence Orientation or Investor Orientation. Thus, emphasis on Post-competence Orientation was independent of the focus on Competence and Investor Orientation. Finally, the firm scored 3.11 on Spiritual Orientation, which was significantly different from its scores on Investor Orientation (difference = 3.18; df=5; p<0.01), Competence Orientation (difference = 2.92; df=5; p<0.01) and Post-competence Orientation (difference = 21 1.79; df=5; p<0.01). However, the Spearman’s rank correlation was not significant for the top manager scores on Spiritual Orientation and any of the other three scales. On the whole, the firm put only “some” emphasis on Spiritual Orientation, “high” emphasis on Post-competence orientation, and “very high” importance on Competence and Investor Orientation. There was an indication that the firm’s top managers took an integrated and stronger view of the Investor and Competence orientation, while taking an independent but positive view of Post-competence Orientation without being overwhelmed by the socialist forces in the West Bengal State. Finally, the top managers gave a non-trivial priority to the Spiritual Orientation in their strategic decision-making, consistent with its significance in the Indian culture. On the whole, the firm appears to operate according to the transformative perspective. Next, we present the findings of the CEO interview to show how this transformative perspective must be created, and cannot be taken for granted. Working Towards the Transformative Perspective Of the seven manufacturing units of Coates of India, the plant at the city of Calcutta (at the Headquarters, in the State of West Bengal) with a workforce of 620 is the largest. The plant experienced a rapid growth in production volumes and values during 1990-95, realizing an enormous growth in productivity, profitability, and value realizations, as shown in Table 3 and Table 4. --------------------------------Insert Table 3 and 4 About Here --------------------------------The increase in production took place with largely stable number of workers, and allowed continued rise in wage incomes for these workers, in profitability for the firm, and in product quality for the consumers, with diminishing costs as the ratio of wage costs to both units produced/ production value showed a significant reduction. The growth was a result of a new 22 business vision, pursuant to the liberalization of Indian economy in the early 1990s and a concomitant change in parent group from Coates Brothers of UK to Totalfina of France. The new vision emphasized substantial modernization of the plant, with sustained increase in the production capacity, and introduction of automated machines and application of latest technologies, in ways that would be labor and skill enabling, rather than labor and skill displacing. Table 5 provides data on the investments made by the firm in Computers and Plant & Machinery at Calcutta Plant. --------------------------------Insert Table 5 About Here --------------------------------The success with modernization in the Calcutta plant, home to India’s one of the most left-leaning workforce, unions and the government, instilled the company with confidence to persist with further investments in computerization and technology improvement in other plants of COI, in the second half of the 1990s. The State of West Bengal was notorious for perpetual strikes, politically sanctioned labor agitation and industrial unrest and sense of animosity between the managers and the workers, which were at their peak during 1960-90. Despite such a historically dismal socio-political context of the workplace, COI led the transformation in the industrial atmosphere of West Bengal during the 1990s. The thrust of COI’s vision was not on incentives – in fact, no incentive schemes were operational in the Calcutta unit. Rather, there was a new sense of collaboration among managers, workforce and the unions, which helped contain the average absenteeism levels to single-digit levels of 710%, avoid overtime costs with mutual consent, and enhanced the productivity and standards of living for the benefit of the workforce, consumers and the investors at the same time. COI’s new model for managing the “living assets” was founded on mutual respect and trust. It recognized the shift in workforce ranks to the fourth generation workers, who were 23 extremely loyal to the firm and were looking at better futures than ones obtained by their predecessors as part of COI. It was built on the confidence that the firm had not experienced any strike or lockout throughout its history, in a socio-political context where these incidents were quite common part of the industrial life. The firm had since its inception resolved all the issues with the workers and the unions through continuous discussions, formalized into annual agreements, signed by both union and the management. This allowed the firm to keep its industrial relations free from political intervention. Now, the new governance environment, both at the corporate level as well as at the national and state level, encouraged the management to bring the two rival unions together, and for seeking a collaborative approach for enhanced productivity of the firm and welfare of the workers, within a framework of modernization, technological advancement, and organizational learning. The Old and the New In the past, especially during the 1980s, the rivalry between the two unions for realizing supremacy among the workforce and having their say in the discussions with management disrupted the organizational climate. Both the unions had about an equal number of members, and each struggled hard to prove their majority showing 49:51 or 51:49 situation almost as a rule. There were always several opportunist members who made the most of this by switching unions on a regular basis and threatening to leave one particular union in the event of not being given a coveted status in the union. Their movement back and forth was a sheer nightmare for most loyalists in the two unions and they tried every trick in the book to win back the lost members. Once it went to the extent of one union coercing members of the other union to join their union by going to their respective houses and making them sign the membership related documents. And consequently the other union made a big hue & cry over this issue. 24 The unions had so many complaints against one another that the management had to employ some selected individuals in management position especially for listening to their problems and negotiate issues separately with each of the unions. The amount of time spent by these people with each of the unions was so much that eventually the persons concerned were jokingly referred to as owning that particular union. Under these conditions, the management had to sit with the two unions separately and it was almost impossible to arrive at any consensus at any given point of time. Any agreement with one of the unions automatically meant opposition from the other union. It was more of a vicious circle with no end in sight in so much that some members of the management thought that classic divide and rule policy would be the best course of action. As the British parent company was mulling its takeover by Totalfina of France, and the new economic policy being introduced in the nation and the state, a new managerial philosophy emerged at COI at the turn of the nineties. The change agent was Dr. P. K. Dutt, who had joined COI in 1970 as a management trainee, after Ph. D. in polymer science and decade-long job as a faculty at University of Arizona over 1960-1970. Dutt rose rapidly to become the first non-British Chief Technical Manager of COI over the next few years. After a 2-year strategy stint at the British head-office, he came back as a General Manager for COI and West African operations of the parent company in 1982. Soon thereafter, he was appointed to the Board of COI in 1984, given charge as Assistant Managing Director in 1986, and eventually made Managing Director (equivalent to CEO) of COI in 1991. Regarding this period, Dutt commented in our interview: “I had no intention of coming back to India when I was posted in UK but I was called here as the company was going through some difficulty. In this context therefore I had a very clear mandate: (1) to modernise the company and (2) to take it forward. Though one should not boast, the subsequent results, however, proved that after I came back the turnover more than doubled and the profit grew to four times during the period 1988-89.” 25 With his appointment as Managing Director, Dr. Dutt and his management team charted out a fresh approach to break the long- standing union impasse. The previous management had worked under the assumption that the existence of two weak rival unions instead of one strong union flexing its muscles was certainly an ideal situation from the control point of view. The belief of the new management was that if they could appeal to the good senses of the workers they would understand the importance of collaboration and unity. No employee, whichever union he belonged to, was interested in petty squabbles and union fights on a daily basis. They were coming to work to earn their daily bread and had enough sense to understand what was good for them in the long run. In other words, the new model was to approach workforce as “loving” and “living” assets, who loved their firm and who would prefer to live in a healthy and vibrant work environment. In words of Dr. Dutt, the model was guided by the changing worldview of competition and strategy: “Till the mid-eighties we had to become competitive against local small-scale companies which had a lot of fiscal advantage and the product did not require any sophisticated technology. Being a British company, on the other hand, we had a very high overhead cost. During that time we could, however, manage to improve our efficiency and survive. From mid-nineties and afterwards, due to liberalisation, our competitors are not the local companies anymore. We have to now compete with anybody, anywhere across the globe and remain really “world-class”. It was not easy for the company to become world-class which was functioning in a country closed for nearly forty years.” Taking the opportunity of upcoming annual agreements with the unions, the management put to test their hypothesis of workforce as ‘loving and living assets’. In response to the two separate charters of demand from the two unions, the management placed a unique and hitherto unheard of proposal. They intended to recognize both the unions as one representing the interests of the entire workforce. They announced that the management would only entertain a joint charter of demands and the process of negotiation and final settlement would only be done with representatives from both the unions attending the meeting. There was an immediate resistance from all the quarters, including members of the management that the new model was doomed to fail. 26 However, the management took a firm stand and adopted the strategy of communicating extensively highlighting the benefits of such collaboration at several meetings with workers on the shop floor. They explained to the workers that the strength in numbers in deciding majority /minority did not make much of a difference to them as the management was committed to treating both the two unions at par. The management would always follow a policy of non-discrimination, recognizing both the unions as representing the interest of the workers. The union leaders resisted this move strongly, fearing to lose the power and attention they had become accustomed to. But the communication exercises of the management were beginning to have a profound effect on the general workers. In this regard, Dr. Dutt observed: “my major strength is my total openness. I don’t hesitate to say the truth straight and value transparency. It might be seen as my weakness as well but I do honestly perceive it as my strength. I could be blunt, if required. I believe that after all the CEO is the leader and if anything is not right the leader has to say it. To tell the truth in the Indian situation speaking the truth may be, often perceived as weakness. Culturally, we are always looking for sympathy. Sympathy for the right reason or the right cause is humane. But sympathy for somebody’s failure does not exist in my book. I believe that everybody should show a sense of responsibility. I also have a very high expectation from people as I believe that performance is truly limitless. Though I at times sound rather blunt, people know that what I tell them is nothing personal based on my liking/disliking. I am always perceived as fair.” The rank and file members recognized the new model as fundamentally designed for their own benefit, and at the same time for enhancement of organizational effectiveness. The union leaders soon gave in to the popular grassroots sentiments, and called a joint meeting for joining hands together and tried to resolve mutual differences on their own without managerial intervention. Finally they decided to accept practically all the pre-conditions of the new model, i.e. they agreed to sit in joint negotiation meeting with the management having equal representatives from both the unions. They also decided to have equal number of representatives for the Works committee and the Canteen Committee where the number of union reps required was even. But the Provident Fund committee seemed to pose a problem, as the number of reps required was three. This was resolved through a management 27 suggestion to have a ratio of representation from the two unions as 2:1 in one year and 1:2 in the next year. In addition, switching between the unions was banned forever. Any new recruit would be given a choice to join any of the union but they would have to remain with that union for life. Though the union leaders vehemently opposed the idea of submitting a single memorandum, they eventually landed up submitting virtually identical copies of Charter of Demands on their union letterheads. As part of the new Code of conduct, built on the message of solidarity, no labor related issue was at all to be discussed from now onwards, without the presence of both the union representative even when discussing issues pertaining to one union only. Further, to contain costs and ensure dedicated work during normal hours, all overtime hours were eliminated with mutual consent. Looking back in 2001, Dr. Dutt noted: “Here, the unions have different political affiliations. But we always talk to them together. I don’t even know who belongs to which union and people often laugh at me for that, but it really does not matter. There are only some token symbols ( like union flags ) but no real politics goes on inside the company. Long back, in mid-eighties I had told them it is their choice whether they want to be a part of a sick company or a healthy business organisation. If they want politicking and unionism they would surely dig their own grave.” Towards a Shared Future Today, after almost a decade, the workplace climate has so transformed that the union members hardly differentiate between the unions. More often than not, they invite the opposite union’s leader to solve intra-union problems, urging that the presence of any one leader would be enough to handle any situation. In the event of any one leader being absent it would be taken for granted that the other leader would intervene. The two union leaders, who used to avoid being seen together in public, now share a very good rapport, and an equal status from members of both the unions. Management is seen as a true friend, guide and philosopher, with umpteen instances where workers, after having been promoted to the 28 managerial positions with adequate experience, still retaining their union memberships. In this regard, Dr. Dutt observed: “I do not believe in any management-union division, which is very artificial in nature. I know almost all the workers personally go, meet and talk to them and they can also talk to me freely. I tell them, “Look, what you are doing is not right” and they listen to me since they know I don’t talk rubbish. I am working in this company for so many years and whenever in Calcutta I go to the factory, at least three-four times a day. I never restrict myself in the office because I don’s believe in running a company from an office.” The success of the “loving and living asset” model has allowed COI to move ahead with several innovative work practices, to face the new era of globalization and competition that is emerging. As part of the annual agreement signed on 2nd January, 2000, to celebrate the new millennium, the management and unions decided to introduce a new night shift, to relocate existing manpower and support further growth in productivity through multi-skilling and flexible learning. Already, there is an increased thrust on training workers to run several machines, instead of limiting them to only one. To capitalize upon the opportunity for enhanced learning, the number of holidays has been reduced to 12 instead of earlier 16, without any extra compensation for these days, which has allowed the company to commit to the enhanced training despite growing competition. The boundary of the jobs has now become flexible, so that in case of shortage of manpower the work never suffers. Further, the workers have been entrusted with tasks, such as quality control, previously entrusted to management staff only. In addition, housekeeping is now a part of everybody’s job. On the other hand, peripheral jobs like security have been contracted with outside agency to allow focus on jobs where the firm can contribute to skill enhancement of the workers. All the workers are now paid through cheque, and are eligible to draw money using an ATM card from zero-balance accounts with a bank. As noted by Dr. Dutt, these developments have taken a fresh meaning with changeover to the Japanese parent: “being a part of DIC, a very large group of companies, COI has access to the very best technology in the world. We are training the people all the time and like any other company the focus is now on cost, we are now much more cost-conscious than we were before.” 29 In summary, the management belief in treating human assets with dignity and believing in their inherent goodness has been key to the development of COI. While the firm has done well in preserving and fostering its human and technical competencies, and responding to the Post-competence challenges, it is looking forward to a renewed integration of these with Investor Orientation. As shown in Table 6, the profits of the firm took a beating in 2000, as compared to the earlier years, on account of increased depreciation and material costs. --------------------------------Insert Table 5 About Here --------------------------------In this regard, a spiritually guided attitude of Dr. Dutt, reflected in the following quote, may prove as decisive in the transformative organization without any discontinuity: “I don’t see or need any major change, which can only happen when there is no proper planning. I believe the changes should be focused on the business process. I do not believe in drastic downsizing because I understand that in this country without any social security system people are really helpless without a job. I firmly believe that in every sick company it is the failure on the part of the management rather than the fault of the workers. I attribute 75% weight to the change of business process and reducing wastage and 25% reducing the number of people. In a country with a tremendous growth potential, in fact, we need people. I welcome the process of automation but I will also like to calculate the real cost-effectiveness. We reduce numbers through a really soft Voluntary Retirement Scheme (VRS) program which basically emphasizes the concept of natural attrition and job-freezing.” Already, Coates of India’s positive climate has become an exemplar in the State of West Bengal, which is now shedding its past image of leftist unionism and moving towards a more positive, meaningful, relationship between the workforce and the management. Conclusions In this chapter, we reviewed the transformative perspective in change, leadership, and learning domains. In its essence, transformative perspective allows an organization to develop a higher-order integrative insights into the differentiated features of various domains, 30 so that a new meaning of change, leadership, and learning is created, which allows the organization to live a fulfilling life in each of those domains. The participants in the organization are also thereby able to share their differences, and develop a shared sense of reality, and construct bridges between their different realms of life. The transformative organizations go to the very purpose of human and organizational life, which pervades all the domains of human and organizational behavior. Thus, transformative approaches influence the heart or culture of the organization, and help generate a new integrative emic meaning of each behavior. We developed a theory of strategic cultures of organizations, identifying four types of strategic cultures – each associated with one region of the world. The four types were Investor Orientation (typical of Western Hemisphere and Anglo), Competence Orientation (typical of Asia-Pacific), Post-Competence Orientation (typical of Europe), and Spiritual Orientation (typical of Africa). We proposed that the globalization creates the challenge for developing an integrative culture, and suggested that the transformative perspective allows the firms to put appropriate proportionate priorities on each of these strategic domains without sacrificing any one of them. We tested the proposition about the integrative strategic cultures of the transformative organization using the analysis of an Indian firm, Coates of India, whose holding shifted from a British parent, to first French parent, and then to Dutch/Japanese parent over the last ten years. Using survey data from the top management team, we found that the firm puts very high priority on Investor and Competence Oriented culture, high priority on Post-competence culture, and some but limited priority on Spiritual culture. The CEO interview further indicated that the firm has enjoyed greatest gains in Competence oriented culture over the recent years, as manifested in a complete transformation of the industrial relations climate, while also building up Post-competence orientation involving the positive effect of this 31 transformation on the local state. The Investor oriented culture has taken some beating in the recent times, but may improve as the firm looks at its role in transformative terms, covering co-development of employees, community, and the nation. 32 Table 1: Item Composition of Strategic Culture Scales Investor Orientation Cost control; firm profitability; product quality; sales volume Competence Orientation Long-term competitive ability of the organization; effect on relationships with other organizations with which you do serious business; employee professional growth and development; employee relations issues; customer satisfaction Post-Competence Contribution to the economic welfare of the nation; welfare of Orientation the local community; environment; minority employees; female employees Spiritual Orientation Ethical considerations; supernatural forces, such as auspicious days and forecasts by truth sayers; pleasing, respecting, not offending a divine being Note: All items evaluate how much importance should be assigned when making critical management decisions, with response alternatives ranging from 1 (none)… 4 (moderate)… 7 (most important) 33 Table 2: Strategic Culture Scores for Coates of India Respondent Respondent Respondent Respondent Respondent Respondent Firm’s 1 2 3 4 5 6 Average Investor Orientation 6.29 7.00 5.50 7.00 5.00 6.50 6.75 Competence Orientation 6.03 6.40 5.80 6.60 4.80 6.20 6.40 Post competence Orientation 4.90 5.20 4.80 4.40 4.40 4.40 6.20 Spiritual Orientation 3.11 3.33 3.00 3.33 2.00 2.00 5.00 34 Table 3: Production Growth at Calcutta Plant of COI during early 1990s DEPARTMENTS PRODUCTION PRODUCTION INCREASE IN BEFORE 90s DURING 94-95 PERCENTAGE LIQUID INKS 2000 3600 80 LIQUID INKS 7 JOBS 10 JOBS 43 1200 2600 117 2000 4000 100 4TONS 7 TONS 75 3 TONS 7.7 TONS 93 BLENDING LIQUID INKS VARNISH PASTE INKS WEIGHING PASTE INKS VARNISH CHIPS 35 Table 4: Growth in Calcutta Plant Productivity over the early 1990s 1990-91 1991-92 1992-93 1993-94 1994-95 148.32 205.73 255.17 277.02 361.25 1605.13 1802.15 1958.65 2150.58 2497.93 Value Added (Rs. Million) 44.88 65.41 80.14 95.71 116.45 Wages (Rs. million) 11.87 12.75 14.74 16.03 17.12 Number of Workmen 240 237 235 234 227 187,000 276,000 341,000 409,000 513,000 138,000 6.69 222,000 7.60 278,000 8.33 341,000 9.19 438,000 11.00 618,000 868,000 1,086,000 1,184,000 1,591,000 7394 7076 7527 7456 6855 8 6.2 5.78 5.79 4.74 0.09 0.11 0.13 0.13 0.14 Production Value (Rs. Million) Production units (in Million tons) Productivity (Rs. Value Added/worker) Profitability (Rs. Valueadded-Wages)/worker Units produced ( in million tons )per workman Production Value ( Rs. per worker) Wage Cost in Rs. / units produced in million tons Wage Cost/ Production Value Unit Realization (Rs/ton) 36 Table 5: Modernization Investments in Calcutta Plant of COI, (Rs. million) Year Computers Plant & Machinery 1994 - 52.257 1995 - 51.049 1996 11.851 24.388 1997 10.347 30.715 37 Table 6: Recent Performance of Calcutta Plant of COI Year Sales Figures( in Profit After Tax( in Production units( in million rupees) million rupees) tons) 1998 1448 85 2531 1999 1642 101 2657 2000 1844 90* 3051 * There was a significant increase in material costs and depreciation leading to reduction in the amount of profits 38 References: Astin, A. and H. Astin. (2001); “Principles of Transformative Leadership,” AAHE Bulletin, January, Washington, D.C.: American Association for Higher Education. Bass, B. M. (1985) Leadership and performance beyond expectations. New York: Free Press. Bemis, W. & B. Nanus. (1985); Leaders: the strategies for taking charge. New York: Harper & Row. Boyd, R.D. & Myers, J. G. (1988);. "Transformative Education." International Journal of Lifelong Education, 7(4): 261-284. Brent, Doug. (1991); "Oral Knowledge, Typographic Knowledge, Electronic Knowledge: Reflections on the History of Ownership." Ejournal 1 (3), Albany, New York: University of Albany. Burgess, H. & Burgess, G. (1996). Constructive confrontation: A transformative approach to intractable conflicts. Mediation Quarterly, 13(4): 305-322. Bush, RAB & Folger, JP (1994). The promise of mediation: Responding to conflict through empowerment and recognition, San Francisco: Jossey-Bass. Dyer, J.J. & Singh, H. (1998); “The Relational View: Cooperative Strategy and Sources of Interorganizational Competitive Advantage,” Academy of Management Review, 23(4): 660– 679. Glock, C.Y. & Stark, R. (1965). Religion and Society in tension, Chicago: Rand McNally. Goeglein, A. & Indvik, J. (2000). "Values-Based Transformational Leadership: An Integration of Leadership and Moral Development Models." Proceedings of the Academy of Strategic and Organizational Leadership, 5(2), 12-16. Gupta, V., Hanges, P.J., & Dorfman, P.W. (2002) “Clustering of GLOBE Societies,” in Cultures, Organizations, and Leadership: GLOBE Study of 62 Nations, Eds. House, R.J., Hanges, P.J., Javidan, M., Dorfman, P.W., Gupta, V., & GLOBE, CA: Sage Publications. Gupta, V., Rajasekar, J., and E S Srinivas, (2002) “Managing Performing Workforce: The Case of India - Challenges and Legacies,” in Pattanayak, B. & Gupta V. (eds.), Creating Performing Organizations: International Perspectives for Indian Management, New Delhi, India: Sage Publications. Kuczmarski, S.S., & Kuczmarski, T.D., (1995). Values-based leadership. Englewood Cliffs, N.J.: Prentice-Hall. Lederach, J.P. (1989); "Director's Circle." Conciliation Quarterly, 8(3): 12-14. Lichtenstein, B. M. B.. (2000); Self-organized Transitions: A Pattern Amidst the Chaos of Transformative Change. (4): 128-141. Academy of Management Executive. 39 Mangaliso, M.P. (2001) “Building Competitive Advantage from Ubuntu: Management Lessons from South Africa.” 15(3): 23-33, The Academy of Management Executive. Meyer, M.W. & Gupta, V. (1994) 'The Performance Paradox', In BM Staw & L. Cummings (eds.), Research in Organizational Behavior, Greenwich, Connecticut: JAI Press, 16: 309-369 Mezirow, J. (1991). Transformative Dimensions of Adult Learning. San Francisco: JosseyBass, Inc. Montville, J.V. (1993). The Healing Function in Political Conflict Resolution. In Conflict Resolution Theory and Practice: Integration and Application, edited by Dennis J. Sandole and Hugo van der Merwe, 112-127. New York: St. Martin's Press. Morris, R. (1994); A Practical Path to Transformative Justice, Toronto: Rittenhouse. Ferguson M (1980) The Acquarian Conspiracy: personal and social transformations in the 1980s, Los Angeles, J P Tarcher. Parker, S.K., & Axtell, C.M. (2001) “Seeing Another viewpoint: Antecedents and outcomes of employee perspective taking,” The Academy of Management Journal, 44(6): 1085-1101. Stryker, S. & Serpe, R.T. (1982). “Commitment, Identity salience, and role behavior: Theory and research example. In W. Ickes & E.S. Knowles (Eds.) Personality, roles and social behavior, 199-218. New York: Springer-Verlag. Vargas, R. (1987) “Transformative Knowledge: A Chicano Perspective,” In Context, 17: 4850, Langley, WA: Context Institute. 40 Figure 1: The Process of Transformative Change