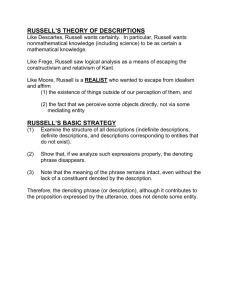

Content, Thoughts, and Definite Descriptions

advertisement