It is a hot day. All of us are sitting at the kitchen table when the

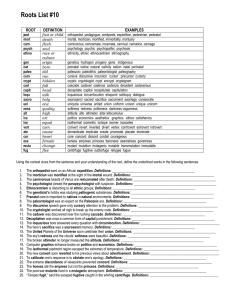

advertisement

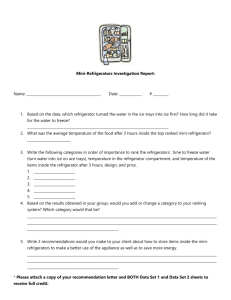

It is a hot day. All of us are sitting at the kitchen table when the mortician enters with an armful of mourning dresses. He puts them on the table and says, “Put these on. The funeral will begin after we move your cousin from the refrigerator to his coffin. If any of you wants to see him for the very last time, go now—otherwise you won’t be able to see him after the move. It’s bad luck, you know.” We begin to stand. One by one, we put on the mourning dresses and falter toward the living room. No one is in the living room. TY’s mother has gone home. The mortician told her to leave because it is a tradition that the parents are not supposed to attend their child’s funeral. It is a cruel tradition, but it makes sense to me. His mother has wept too much in these days. I doubt if she could make it through the whole funeral. The living room is empty. All the furniture is moved to the storeroom. In the center of the room is a desk with a censer and TY’s picture placed on it. The mortician and his flunkies decorated the desk with some sort of necromantic streamers and behind the desk is the refrigerator where TY’s dead body rests. I am the first to see him. I walk to the refrigerator and bend down to see my cousin for the last time. Under the glassy pane is TY’s pretty face. I always think he resembles Takuya Kimura a lot. Both TY and Kimura have heart-shaped face, straight nose, and big round eyes. And his smile, very much alike Kimura’s, creats an innocent air. I remember there used to be girls waiting at the door. “Lady’s man,” his father always said, “ my son’s a lady’s man.” True. TY knows how to make people laugh. He just knows how. No tricks. He was born with it. With his pretty face, no girl would ever turn him down. “It’s a miracle,” my cousin Helen says behind me. “Look, his face is not burnt.” A miracle? I don’t think so. I never believe in this kind of crap. If there was a miracle, TY shouldn’t have died. He must have shielded his face from the blast. I still remember seeing him behind the window of the intensive care unit. His whole body was carefully tucked in green sheet. According to his doctor, TY was pretty much fucked up. He had third-degree burns over almost his whole body. His left leg was amputated no sooner he was sent to the hospital. The doctors had done what they could, but still, they failed to save TY’s life. It happened on the Chinese New Year’s eve. TY was found on fire in the surburbs. Someone poured gasoline all over his body and lit a fire. Our DanBing cops (Taiwanese cops prefer eating DanBing to donuts) were incompetent to catch the murderer, especially when the victim was unable to talk. There were rumors about the murder: TY was a drug addict. He tried to quit and be his mama’s good boy again. He found a proper job and he worked hard. However, his scoundrel friends came to him and wanted him back to the gang. He probably refused the offer and got in trouble. Or, as my aunt suspects, TY killed himself because drug quitting involved a great pain. “Are you all finished?” the mortician says, “Please go back to the kitchen. We’ll begin to move his body now.” “Mind if we watch?” I ask. “Yes. You are not supposed to watch us moving his body. It’s bad luck.” Another stupid tradition. However, it’s not the time to argue with him. My cousins and I walk back to the kitchen and sit at the same table waiting for the mortician to call. Nobody speaks except the fan turns weakly. The stillness starts to make me feel dizzy. I think about TY and his Kimura smile. The mortician enters. “Come on. It’s about time to begin.” Slowly we raise, and we are ready to send TY away.