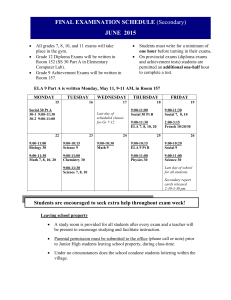

high stakes testing law and litigation

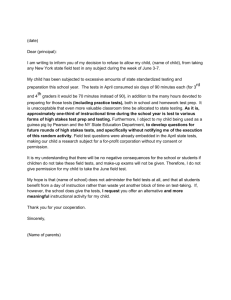

advertisement