Cי Separation of Religion and State in Stable Christian Democracies

advertisement

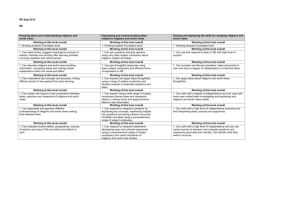

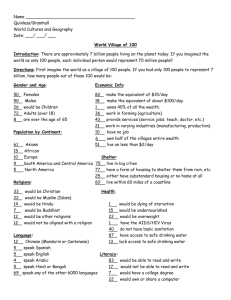

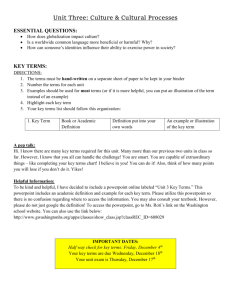

יC Separation of Religion and State in Stable Christian Democracies: Fact or Myth? Jonathan Fox Department of Political Studies Bar Ilan University Abstract: This study compares separation of religion and state (SRAS) as it is conceived in theory to whether it exists in practice in 40 stable Christian democracies between 1990 and 2008 using data from the Religion and State round 2 dataset. There is no agreement in the literature on how SRAS ought to be conceived but many argue that SRAS is a necessary precondition for liberal democracies. Accordingly this study examines four models of SRAS found in the literature as well as a non-SRAS model that addresses the appropriate role of religion in democracies: secularism-laicism, absolute SRAS, neutral political concern, exclusion of ideals, and the acceptable support for religion model. An analysis of the extent of religious legislation and restrictions on the religious practices and institutions of religious minorities shows that depending on the definition of SRAS used between zero and eight of these 40 countries have SRAS. Based on this, I conclude that either SRAS is not a required precondition for liberal democracy, or many states that are commonly considered liberal democracies are, in fact, not liberal democracies. Within some intellectual circles, there is an assumption that Christian liberal democracy and separation of religion and state (SRAS) go hand in hand. Yet many dispute this notion. This study examines and tests the actual extent of SRAS among 40 stable Christian democracies between 1990 and 2008 using the Religion and State round 2 (RAS2) dataset, focusing on two aspects of SRAS: religious legislation and religious discrimination. Conceptions of Religion and State The assumption that the proper and natural relationship between religion and state, at least in Christian democratic states, should be SRAS is present in many intellectual circles. For example, a recent call for papers by the Journal of Law, Religion, and State states that: The relations between religion and the democratic state are based to a large extent on separation between public and private domains. In the public domain the state enjoys full supremacy while in the private domain every person enjoys freedom of religion. In the public domain neutral and secular discourse should prevail and there is no room for religious arguments per se, especially not for recourse to religious authority. In the private domain religious authorities can preach and invoke religious principles. This separation is based on a certain assumption, grounded in a Protestant conception regarding the nature of religion. It assumes that religion's prime concerns lie in the realm of belief and private life. 1 יC Therefore, the demand that religion won’t interfere with state affairs does not clash with religious principles. Stepan (2000: 39-40) in his classic study of religion and toleration similarly describes this school of thought: Democratic institutions must be free, within the bounds of the constitution and human rights, to generate policies. Religious institutions should not have constitutionally privileged prerogatives that allow them to mandate public policy to democratically elected governments. At the same time, individuals and religious communities...must have complete freedom to worship privately. In addition, as individuals and groups, they must be able to advance their values publicly in civil society and to sponsor organizations and movements in political society, as long as their actions do not impinge negatively on the liberties of other citizens or violate democracy and the law. Perhaps the most well known version of this normative plea can be attributed to Rawles (1993: 151) who argues that we must “take the truths of religion off the political agenda.”1 However, this normative plea is not unopposed. Classically, de Tocqueville is usually paired against Rawls to argue that there is room for religion in democracy. In fact he argues that a “successful political democracy will inevitably require moral instruction grounded in religious faith.” (Fradkin, 2000: 90-91) Greenawalt (1988: 49, 55) similarly argues that liberal democracy tolerates people who want to impose their religious convictions on others “just as it tolerates people who wish to establish a dictatorship of the proletariat” and that without resort to religion there are often insufficient “grounds for citizens to resolve many political issues.” Bader (1999) argues that excluding religion from the public sphere or even just from government is discriminatory and violates liberal values. For instance, why should it be only secular institutions that can receive government contracts to provide services? Some go as far as to argue that aggressive secularism can become hostility to religion which violates liberal values. (Durham, 1996: 19) On a more practical level, many argue that this assumption of universal SRAS among Christian democracies does not fit the facts. (Cassanova, 2009: 1058; Fox, 2008) and there is no shortage of democracies which openly endorse specific religions. (Fox, 2008; Stepan, 2000: 41-43) Some go as far as to argue that democracy is not possible in religiously plural societies. (Mill, 1951: 46; Horowitz, 1985: 86-86) Lijphart (1997), among others, developed the concepts of consociationalism and power sharing to describe religiously plural societies that could only endure democracy through complex power sharing arrangements. There is also a strain of arguments which posit that under the correct circumstances, state support for religion does not harm democracy. Mazie (2004; 2006) argues that this is possible because there are some elements of religion are compatible with democracy while others are not. He differentiates between supporting a religion and making it mandatory with the former being acceptable and the latter not. Driessen (2010) argues that as long as a government has sufficient autonomy to make decisions independent of religion–without religious actors being able to 1 For additional versions of this argument see, among others, Demerath (2001: 2) and Shah (2000). 2 יC overrule its decisions—further separation is not necessary in order to have high levels of democracy. Marquand & Nettler (2000) similarly argue that religion and democracy can co-exist if there is mutual tolerance, or at least mutual self-restraint on the part of both religion and government, and a right got the non-religious to abide by their own values. Even among those who advocate some form of SRAS, there are multiple conceptions of the concept, many of which do not confirm to the normative pleas cited above. Western conceptions of SRAS can be divided into four categories. These categories basically represent different answers to the following questions: (1) May the state support religion? (2) May the state restrict religion? (3) Is religious discourse and expression appropriate in the public sphere? The four conceptions of SRAS discussed below are presented in Table 1 below in light of these three questions. Table 1 also presents the theory of acceptable support for religion as discussed by Mazie (2004), Driessen (2010), and Marquand & Nettler (2000) above. This final theory, while not a theory of SRAS, does address the appropriate role of religion in democracies. [Table 1 about here] The secularist-laicist model not only bans state support for any religion, it also restricts the presence of religion in the public sphere. Thus not only are restrictions on religion in the public sphere allowed, they are mandated. Religion is a wholly private matter and the state enforces this through restrictions on public religious activities and on religious institutions. (Kuru, 2009; Hurd, 2004a; 2004b; Haynes, 1997; Keane, 2000; Stepan, 2000; Durham, 1996: 21-22; Esbeck, 1988) These restrictions are placed on all religions equally, including the majority religion. France's 2004 law banning any overt religious symbol in public schools, including the head coverings worn by Muslim women, is a classic example of this model. While someone from another tradition might consider this law a restriction on religious liberty, from the French perspective these religious symbols constitute an aggressive encroachment of religion—something that should be a private matter—on the public sphere. The other three models are variations on the expectation that the state should maintain neutrality toward religion. While these models do not require a particular stance on religion as a negative or positive influence on society, they are compatible with a view of religion as a positive influence. This is qualitatively different to laicism-secularism in that laicist-secularist governments act as if religion is a negative influence and must be relegated to the private sphere. These neutralist models take the stand that the state should not be privileging any particular religion, but accomplish this in different ways. While the terms for these models differ across the literature I will rely on those developed by Fox (2007; 2008), Madely (2003) and Raz (1986). The second model is absolute SRAS. This conception requires that the state neither support nor restrict any religion. This is perhaps the strictest of the 'neutral' models because it allows no government involvement or interference in religion at all, though within this trend, opinions on the proper role of religion in civil society and political discourse differ. (Esbeck, 1988; Kuru, 2009) The US is often considered the prime example of this model. While there is a difference of opinion within supporters of this model on specifics, there is general agreement that religion should not be the business of government but the expression of religion in public life is not only acceptable, it is a positive influence. (Kuru, 2009) 3 יC Esbeck (1988) identifies three trends in US thought within this tradition. Strict separationists, believe that public policy should be decided on a secular basis, and there is “no universal, transcendent point of reference or ethical system exists or is required for judging the state.” This is also known as the "Jeffersonian" wall between religion and state. That being said, within this school of thought the public expression of religion is not excluded. The pluralist separationist school of thought accepts that "religion may influence issues of civic government" but recoils "at the thought of a religiously generated cultural mandate employing the offices of government to achieve religious ends.” (Esbeck, 1988: 45) Finally, institutional separationists allow for religious moral traditions to influence political discussion but are against state support for religion or the use of state instruments to advantage a particular religion. The third model, neutral political concern, has a different conception of state neutrality toward religion. This model "requires that government action should not help or hinder any life-plan or way of life more than any other and that the consequences of government action should therefore be neutral." (Madeley, 2003: 56) That is, government support for religion and restrictions on religion are acceptable as long as they are applied equally to all religions. The fourth model, exclusion of ideals, has a similar conception of neutrality but focuses on intent rather than outcome. It mandates that "the state be precluded from justifying its actions on the basis of a preference for any particular way of life." (Madeley, 2003: 6) Thus religions can in practice be treated differently as long as there is no specific intent to support or hinder a specific religion.2 The fifth model, which is not a form of SRAS, is based on theories of acceptable support for religion in democracies as discussed by Mazie (2004), Driessen (2010), and Marquand & Nettler (2000) above. It is in some ways stricter than all but the absolute SRAS model. This set of theories allows support for a single religion but otherwise fully protects religious freedom in general and the religious expression of minorities. Thus, governments may support a religion, but it may not restrict any religion, especially minority religions, and it may not make any aspect of religion mandatory. While the differences between the four models of SRAS models are significant, it is important to emphasize that they all, along with the model for acceptable support for religion, have one thing in common: that religious minorities should be as free to practice their religion as the majority religion. That is, all five of these models agree that a lack of religious freedom for religious minorities that is not shared by the majority is unacceptable. For absolute SRAS and the acceptable support model, any restriction on minorities is unacceptable. Such restrictions, effectively creates two categories of religion: (1) the favored religion (or favored religions) and (2) all other religions. This lack of equality in how religions are restricted runs counter to all four models of SRAS, as well as the standard for acceptable support form religion in democracies but for different reasons. Also, in the exclusion of ideals model it is possible for a religion to receive benefits not given to other religions. Also, on a more general level, the normative calls for SRAS, even though they focus on state support for religion include this requirement for religious freedom. The call for papers noted above explicitly states that "in the private domain every person enjoys freedom of religion." Similarly, Stepan (2000: 39-40) states that "individuals and religious communities...must have complete freedom to worship privately." 2 For a discussion of what types of state support for religion can violate the principle of state neutrality toward religion see Driessen (2010) and Mazie (2006). For a review of the Western intellectual history of the concept of separation of religion and state see Laycock (1997) and Witte (2006). 4 יC It is important to emphasize that while in theory, any limitation on religion is a limitation of religious freedom, all states restrict religion in some instances. For example, should a religion call for human sacrifice, no government would grant an exception to laws banning murder despite that doing so would technically violate the right to practice one's religion freely. This is an extreme example of the general concept that governments must balance priorities, of which freedom of religion is only one. A more common example is zoning laws which might limit the ability to build places of worship in particular locations. If this is applied equally to all religions, this would be an instance of general regulations that apply to all equally and, for the purposes of this study, would not be considered religious discrimination. It is arguably not even a restriction on religious freedom if places of worship can, in general, be built in places other than these particular locations, especially if any denomination that wishes to build one can find a reasonable place to do so. An example of this would be a ban on any structures non-residential structures in an area zoned exclusively for residential structures. Zoning laws applied selectively to limit the ability of only certain religions to build places of worship are another matter entirely. This means that a state which maintains no support for religion but limits the religious freedom of minorities in ways not applied to the majority religion clearly violates basic elements of the principles of all manifestations of SRAS doctrines and even standards for democracies that do not require SRAS. Accordingly in this study, I examine religious discrimination in addition to religious legislation. As is demonstrated below, most Christian democratic states either declare official religions or openly support one or a few religions more than others, totally eschewing any adherence to this aspect of SRAS. In addition most of them somehow limit the religious freedom of religious minorities in a manner not applied to the majority religion. The purpose of this study is to examine to what extent SRAS, exists, if it exists at all, in stable Christian democracies. Research Design This study uses the Religion and State round 2 (RAS2) dataset to examine the presence of religious legislation and discrimination in Christian democracies. RAS2 includes data on 51 specific types of religious legislation (which are listed in table 4) and 30 specific types of religious discrimination (Which are listed in table 6) for 177 countries coded yearly for the 1990 to 2008 period. This study selects from these 177 countries, all 40 countries which have the following characteristics: (1) They are all stable democracies. I operationalized this by defining a democracy as a state which scores 8 or higher on the Polity scale of democracy. This scale measures democracy on a scale of -10 (most autocratic) to 10 (most democratic). Furthermore, to qualify a country must have scored 8 or higher for the entire 1990 to 2008 period.3 Countries which came into existence after 1990 were included if they were democracies since their independence. (2) Because the Polity dataset is my yardstick for democracy, I did not include states which were not included in the polity dataset. This resulted in the removal of several Western countries with populations of less than one million which are in the RAS2 dataset but not the Polity dataset which generally includes states with a population of one million or higher. (3) They are Christian majority 3 For more on the Polity dataset see Jaggers & Gurr (1995) and the Polity website at http://www.systemicpeace.org/polity/polity4.htm. 5 יC states. This is because the literature links the tradition of SRAS to Christian democracies. These criteria combined provide the 40 states which are most likely to have SRAS according to the theory that Christian liberal democracies are expected to meet this requirement. As, in theory, these states constitute the most favorable environments for SRAS, if they do not have SRAS, this falsifies claims that SRAS is central to democracy. For the purposes of analysis I categorize these states as follows. First, I divide them into world regions: Western Democracies (21 states), the former Soviet bloc (8 states), and a combined Latin America and Asia group (11 states). This is primarily because the tradition of Christian democracy is most strongly associated with the West. I combine Latin America and Asia because there are too few Christian democratic states which meet the criteria for this study in Asia for a separate analysis (2 states). This categorization allows an evaluation of whether the SRAS assumption holds true in these states. I also analyze separately Catholic and non-Catholic states, both having 20 states, because the literature associates democracy more with Protestantism. Both of these variables are included in RAS2 The analysis includes five stages. The first examines whether these countries have an official religion or prefer some religions over others—a violation of all of the concepts of SRAS noted above. RAS2 includes a 15 category variable which measures this which I simplify here into the following categories: The state has an official religion. The state has no official religion but gives privileges and preferences to a single religion. The state has no official religion but gives privileges and preferences to more than one religion. The state supports all religions equally. No support or minimal support for religion. I test how many states fall into each category for both 1990 (or the earliest year of data available) and 2008 to check whether states, on a basic level, meet the expectations for SRAS in liberal Christian democracies. In all analyses after this one, states with official religions are treated separately because assumptions of separation of religion and state clearly do not apply to them. The second stage analyzes mean levels of religious legislation in 1990 (or the earliest year available) and 2008. This is accomplished by adding all of the 51 separate categories of religious legislation to form a scale of 0 to 51. Put differently, this scale measures the number of types of religious law that exist in a country. I examine these results for all cases as well as based on the categorizations noted above separating out states with official religions, by world region, and by majority religious denomination. The purpose of this analysis is to determine whether religious legislation is, in fact, prevalent in Christian democracies. A significant presence of religious legislation in Christian democratic states would falsify predictions of SRAS in these states. The third stage analyzes each of the 51 types of religious legislation separately. The purpose of this analysis is to examine the more specific nature of the religion laws that exist in Christian democracies. As noted in the literature review section, there are different types of support for religion which have different implications. In addition, this is also to determine whether any findings of the 6 יC presence of religious legislation are being driven by a small number of types of legislation or whether it represents a wider range of types of legislation. Due to the large amount of information this analysis must present and that (as is discussed in detail below) there was little change over time in the amount of religious legislation I limit this analysis to 2008. The fourth stage analyzes the religious discrimination variable in the same manner as stage two analyzes religious legislation. The religious discrimination variable is coded on a scale of 0 to 34 so its 30 components added up form a scale of 0 to 90. The purpose of this analysis is to determine whether religious discrimination is, in fact, prevalent in Christian democracies. If found to be present, this would falsify predictions of SRAS in these states. It is important to note that religious discrimination measures restrictions placed on the religious practices or institutions of any minority religion in a state that are not placed on the majority religion. While restrictions placed on all religions, including the majority religion, can be restrictions on religious freedom, they are not discrimination because discrimination implies differential treatment. This operationalization is also consistent with theories of SRAS which demand equal treatment for minority religions. Thus, unequal treatment would not include cases where minority religions are restricted in the same way as the majority religion. The fifth stage analyzes the 30 types of religious discrimination in the same manner as stage three analyzes the various types of religious legislation. The purpose of this analysis is to examine the more specific nature of the religious discrimination that exist in Christian democracies. Space limitations prevent a full description of RAS2 but some relevant aspects require discussion. RAS2 focuses on government policies, institutions, practices, and laws rather than on civil society or religiosity. The variables are coded at the national level and do not include the behavior of regional or local governments unless a significant plurality of these governments engage in a codeable behavior. They reflect either laws on the books or consistent government policy.5 (Fox, 2008). The coding procedures and sources for the dataset are set out in detail in the RAS2 codebook.6 In brief each variable is coded separately for each year between 1990 and 2008. The codings are based on multiple sources listed in detail the RAS Round 2 codebook which include human rights reports from government and private organizations, academic sources, news sources from the Lexis/Nexis database and primary sources including state constitutions and laws. Data Analysis and Discussion Official Religions and Support for Religion The extent of state support for religion, presented in table 2, in and of itself falsifies the Christian democracy SRAS assumption. As will be recalled while some conceptions of SRAS require no support for any religion, some allow for support as long as it is provided equally to all religions. In 2008, these two categories constitute respectively 15% and 10% of all Christian democratic states, a total of 25% of all 4 The scale is as follows: 0- Not significantly restricted for any minorities; 1- The activity is slightly restricted for some minorities; 2- The activity is slightly restricted for most or all minorities or sharply restricted for some of them; 3- The activity is prohibited or sharply restricted for most or all minorities. 5 This focus on national level behavior and government policy is similar to other major data collections on religion and human rights such as Grim & Finke (2006) and Cingranelli & Richards (2006). 6 Available at the RAS website at www.religionandstate.org. 7 יC relevant states. When looking at the categorizations this ranges from 0.0% for former Soviet states to 36.3% for Latin American and Asian states. Thus, in all categories of Christian democratic states, including Western democracies which are the core of the Christian democracy SRAS assumption, a significant majority of states do not have SRAS because some religions are privileged over others. [Table 2 about here] Furthermore, seven of these states had official religions in 2008, eight if one counts Sweden which had an official religion until 2000. Yet these countries, Bolivia, Costa Rica, Denmark, Finland, Greece, Norway, and the UK are all established democracies and five of them are Western democracies. In fact these five Western democracies number are perfectly balanced by the five Western democracies which are coded in RAS2 as having SRAS—Australia, Canada, France, the Netherlands, and the US. If we add in countries which privileged a single religion without having an official one, in 2008 40% of all Christian democracies including 42.8% of Western democracies in some way supported a single religion more than all others. This runs directly counter to the proposition that "the relations between religion and the democratic state are based to a large extent on separation between public and private domains." An additional 35.0% of states favored some religions over others. In some cases this is a simple system with some religions being granted privileges and some not. For example in Belgium there are currently six "recognized" religions— Catholicism, Protestantism, Anglicanism, Judaism, Islam and Christian Orthodoxy as well as “Laïcité”, which is an organization of Secular Humanism that, for all practical purposes, is considered the seventh recognized religion. These religions receive privileges including government funding and privileged access for chaplains.7 In more complicated cases there are multiple tiers of religions. Hungary, for example, has three tiers: (1) four "historical" religions which receive most state funding. (2) Other religions can register and receive some funding. (3) Non-registered religions are not officially limited but receive no state support and since they are not registered entities, do not get the tax benefits of registered and historical religions.8 Lithuania is a particularly complicated case with four tiers: (1) "Traditional" religions are those nine denominations that have been in Lithuania for at least 300 years. They receive annual subsidies from the government, may provide religious instruction in public schools and maintain chaplains in the military. Their clergy and theological students are exempt from military service, and the highest clergy are eligible for diplomatic passports. They may register marriages, establish subsidiary institutions and do not have to pay social and health insurance for clergy and other employees. (2) State-recognized religious groups, a status that can be achieved only after being registered in the country for 25 years, are entitled to perform marriages and are entitled to certain tax-breaks, but do not receive subsidies from the 7 U.S Department of State International Religious Freedom Report 2003, 2004,2005,2006,2007,2008 Online: http://www.state.gov/g/drl/rls/irf/2008/108437.htm; Human Rights Without Frontiers, Online: www.hrwf.net “Denial of Spiritual Assistance to Prisoners Not Professing a State-Recognized Religion” 8 US Department of State, Bureau of Democracy, Human Rights, and Labor, Country Reports on International Religious Freedom 2002, 2003, 2004, 2005, 2006, 2007, 2008, 2009: Hungary, Available at: http://www.state.gov/g/drl/rls/irf/index.htm; Uitz, Renata, “Aiming for State Neutrality in Matters of Religion: The Hungarian Record,”. 8 יC government or exemptions from military service. Since 2005, both State-recognized and traditional religious groups receive social security and health care subsidies for spiritual leaders and employees. (3) Registered communities require at least 15 adult Lithuanians and can act as legal entities, open bank accounts, act in a legal capacity and own property for constructing religious buildings. (4) Unregistered communities have no privileges, but are not prevented from worshipping.9 All of these cases represent the giving of privileges to religions considered indigenous, excluding religions that are less established in the country from these benefits. When combined with states that support a single religion, either officially or unofficially, this covers 75.0% of Christian democracies in 2008. This is an overwhelming lack of SRAS. Religious Legislation The analysis of the extent of religious legislation, presented in table 3, provides similar results. The average Christian democratic state with no official religion had over six and a half types of religion laws in 2008. This remained relatively consistent over categorizations which ran from 5.22 in Latin American and Asian states to 8.25 in former Soviet states. More interestingly, in 2008 no state had less than two types of religious legislation. Thus, if one uses the standard of no religious legislation to measure SRAS, no Christian democracy meets this standard. [Table 3 about here] Furthermore, most states have substantially more than two types of religious legislation. Among states without official religions, 59.4% had at least five types and 12.5% had at least nine types. This finding that many Christian democratic states have many types of religious legislation is consistent across all categorizations. Not surprisingly, the most religious legislation is found in states with official religions. As shown in table 4, there is a wide variety of specific types of religious legislation with 35 of the 51 types of religious legislation being present in at least one Christian democracy, 31 of them in Christian democracies with no official religion. In this analysis of table 4, I focus only on states with no official religions. This is in order to demonstrate that even in Christian democratic states with no official religion there is considerable support for religion. [Table 4 about here] The most common type of legislation is financial support for religion. Of the ten most common categories of legislation, five of them involve financial support for religion. 63.3% of states with no official religions financially support private religious schools. This is common in all categories but least common in Latin America where only 45.5% of Christian democracies without official religions support private religious education. For example, the Australian government provides financial aid to private schools—a majority of which are faith based—and which are attended by approximately 33% of Australian students.10 Brazil also makes federal aid available to 9 US State Department Report on Religious Freedom, 2003 to 2008 Online: http://www.state.gov/g/drl/rls/irf/2004/127321.htm 10 Sydney Morning Herald (Australia), June 26, 2008 9 יC religious schools for education purposes.11 These cases are typical of the larger pattern. 42.4% of states with no official religions financially support clergy. For example in Belgium, the Federal Government pays the salaries, pensions and other expenses of ministers from recognized religions.12 Similarly, Hungary, which as noted above gives special privileges to its four "historical" religions funds the clergy for these religions in small towns. 33.3% of these states directly fund religious organizations from the national budget. For example, the Swedish government's Commission for State Grants to Religious Communities is a government entity which consists of 22 registered religious groups (and 15 sub-groups) who are entitled to some form of direct financial aid.13 Similarly, in Trinidad and Tobago, the Office of the Prime Minister's Social Service Delivery oversees the annual financial grants to religious organizations, and issues recommendations on land use by those organizations.14 The above category is separate from the 27.3% of these states which collect taxes on behalf of religions. While in the above category, the government gives money to religious organizations from its general budget, a religious tax is a separate tax which is explicitly for religion. Exactly half of the Western democracies with no official religion engage in this practice. Austria collects a tax of 1.1% of income on behalf of its 13 officially recognized religions. It is compulsory for Catholics. In Belgium, tax-payers can direct their tax to a designated religion but the tax is compulsory whether or not one is religious. In Germany the tax is 8% to 9% of the amount paid in income tax but is compulsory only for members of recognized religious communities. In Italy, some recognized religions get funds from a voluntary check off on income tax forms which designates that some of this income tax be given to the religious organization. In Portugal, the Catholic Church maintains an agreement with the government allows citizens to donate 0.5 percent of their annual income taxes to the Church. Spain similarly allows citizens to donate up to 0.7 percent of their taxes to the Catholic Church. In Sweden, taxpayers may choose to divert the tax to the religious group of their choice or receive a tax reduction. In Switzerland the issue is decided by the Canton's government. In some Cantons, the church tax is voluntary, in others, a person opting to not pay the Church tax is forced to leave the church, or the tax may be non-negotiable.15 30.3% of states with no official religions fund the building, maintaining or repairing of religious sites. France, despite its militant secularist policy, still occasionally finds ways around an official ban on such funding. In June of 2006, a International Coalition for Religious Freedom, “Brazil” (2009) Available at: http://www.religiousfreedom.com/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=118&Itemid=29 12 U.S Department of State International Religious Freedom Report 2003,2004,2005,2006,2007,2008 Online: http://www.state.gov/g/drl/rls/irf/2008/108437.htm 13 US Department of State Report on Religious Freedom, 2006, 2007, 2008. Online: http://www.state.gov/g/drl/rls/irf/2006/71410.htm, The Wall Street Journal, “In Europe, God is (Not) Dead”, by Andrew Higgins, July 14, 2007 14 US Department of State, International Religious Freedom Report, 2003,2004, 2005, 2006, 2007, 2008. Online: http://www.state.gov/g/drl/rls/irf/2003/24523.htm 15 Department of State Report on Religious Freedom, 2002-2008. Online: http://www.state.gov/g/drl/rls/irf/2006/71410.htm; "Church Tax" Wikipedia, http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Church_tax; Human Rights Without Frontiers, Online: www.hrwf.net “Human Rights in Belgium Annual Report”; “Are Swedes Losing Their Religion?” by Charlotte Celsing, September 1, 2006. Online: http://www.sweden.se/eng/Home/Work-live/Societywelfare/Reading/Are-Swedes-losing-their-religion/, The Washington Post, “Sweden Separates Church, State”, by T.R. Reid, December 30, 2000. 11 10 יC municipal council decided to facilitate the building of a mosque in Marseille by providing land for a nominal fee; the decision- considered to be a violation of the separation of church and state- was annulled in April of 2007.16 In April of 2009, the municipal government of Epinay-sur-Siene opened a 1400 seat “prayer hall” that was financed with public money; in reality the center functions as a mosque.17 In Paris, there are plans to use public funds for the building of a cultural institute on Islam; the “institute” will also function as a house of prayer.18 Despite vocal opposition, the local mayor of the town of Ploermel has used public funds to erect a giant statue of Pope John Paul II, next to a cross.19 While it is possible to argue that the other forms of funding here are what Mazie (2004; 2006) would consider support that does not restrict the religious freedom of non-funded religions, it is more difficult to say this with regard to religious taxes. In some cases these are compulsory taxes which are given to religions. One aspect of religious freedom is the freedom not to be religious. The concept of requiring a non-religious person to pay a religious tax, I posit, violates this principle. Also, the collection of religious taxes by governments is a serious entanglement between religion and state. The other five most common forms of religious laws are not directly related to financing religion. The most common is the presence of religious education in public schools which occurs in 87.5% of Christian democratic states with no official religions. With the exception of Cyprus, where the courses are mandatory for members of the Greek Orthodox Church, in all of these countries the classes are optional or there is a mechanism for students to opt out of the classes. With the exception of Australia, Cyprus, Ireland, Sweden and Trinidad and Tobago, there are no classes available for at least some significant religious minorities. Interestingly in 17 of these countries, the classes are taught by clergy or teachers appointed by religious institutions. Thus, this very common support for religion often allows religious organizations to send representatives to teach religious theology during school time for primary and secondary school students and does so only for some religions and not others. Two of the top ten types of legislation are bureaucratic. 48.5% of these countries have government departments concerned with religions. In 66.6% there exists a process for registering religions which is somehow different from registering other non-profit organizations. However, this registration is technically mandatory only in Bulgaria, Peru, the Philippines, the Solomon Islands, and Uruguay, and in practice religions which do not register are not restricted even in these countries. In 33.3% of these countries people married by clergy receive civil recognition for their marriages. This is not referring to cases where a civil license is obtained but the ceremony is performed by clergy. Rather, a religious marriage is automatically recognized. Finally, abortion is restricted in 45.5% of these countries. While, this is not strictly supporting religion, abortion is an issue that is linked strongly to religious 16 U.S Department of State Religious Freedom Report, 2007. Online: http://www.state.gov/g/drl/rls/irf/2007/90175.htm 17 Human Rights Without Frontiers, “Financing of Islam: When Public Powers Circumvent the Sacred Principal of Laicite”, April 21, 2009. Online: www.hrwf.net 18 Human Rights Without Frontiers, “Financing of Islam: When Public Powers Circumvent the Sacred Principal of Laicite”, April 21, 2009. Online: www.hrwf.net 19 Human Rights Without Frontiers, “Pope Statue Goes Up in France Despite Protests”, December 4, 2006. Online: www.hrwf.net 11 יC beliefs. These restrictions are considerably more common in Catholic majority countries, especially in Latin America where all Christian democracies restrict abortions. If one accepts the state officially supporting no religion more than others as the appropriate standard for democracies, as noted in the previous section, in 2008 only ten of the 40 Christian democracies meet this standard. If one requires stricter standards, this number drops. For example, of one requires, in addition to not supporting some religions more than others, no more than a minimal amount of religious legislation, say five or less of the types of laws included in RAS2, it drops to eight. If one requires no laws whatsoever, no Christian democracy meets this standard. Thus, even under the most generous applied definitions which look only at religious legislation, a large majority of Christian democracies, do not have SRAS based on a definition of no preference for any religion and no government entanglement with religion. Also, while RAS2 does not collect systematic information on whether government financial support for religion is given equally to all religions, the anecdotal evidence cited above demonstrates that this is rarely the case. Thus, most of these states also violate the concept of neutrality—treating all religions equally. Religious Discrimination The final element of SRAS tested here is freedom of religion for all residents, especially minority religions. Any religious discrimination—defined here as restrictions placed on minority religious practices or institutions not placed on the majority—would violate this standard which is an element of all four models of SRAS noted in this study, as well as the acceptable support model. As shown in table 5, religious discrimination is ubiquitous in Christian democracies. 32 (80%) of these states engage in at least some religious discrimination. This includes all of the eight states which had official religions at some point during the 1990 to 2008 period and 24 of the 32 (75%) states with no official religion. These results remain consistent when controlling for region and majority religion with the sole exception of religious discrimination being particularly low in Latin American Christian democracies. This runs directly counter to assumptions that the strongest support for religious freedom can be found in Western democracies. [Table 5 about here] In 2008 the mean level of religious discrimination was 6.00. This means that the average state engaged in the most extreme levels of two types of religious discrimination or in less extreme manifestations of as many as six types. This indicates non-trivial levels of restrictions. Furthermore, the extent of religious discrimination increased between 1990 and 2008, with statistical significance for all cases as well as for several of the sub-categories. While we would not expect states with official religions to refrain from legislating religion, we can expect them to refrain from religious discrimination. This is precisely the argument set out in the acceptable support model by by Mazie (2004; 2006), Driessen (2010), and Marquand & Nettler (2000)—that a state can support a religion without limiting the religious freedom of members of other religions. As already noted, none of the states which have official religions meet this standard. 12 יC They all place at least some restrictions on religious minorities, as do 75% of states with no official religions. An examination of the specific types of religious discrimination in all 40 Christian democracies, presented in table 6, shows the presence of a wide range of types of restrictions on minority religious practices and institutions. 22 of the 30 types of religious discrimination measured by RAS2 are present in at least one Christian democracy. [Table 6 about here] Seven of these are present in more than 20% of these states. The most common restriction is that minority religions must register in order to be legal or receive a special tax status that is automatically granted to the minority religion. This type of law which is present in 52.5% of Christian democracies involves a registration process specific to religions—as opposed to religions registering on the same manner as any nonprofit or charitable organization—is usually benign in that the registration is usually pro forma, all religious communities which seek to do so are able to register and those which choose not to register can practice their religions freely. However, there are numerous exceptions to this. For example in Greece, religions such as the Bahai are denied registration. Such religions cannot receive "house of prayer" permits, must operate as civil “associations”, and cannot function as legal entities.20 13 of these states require a minimum number of members to register and eight mandate a waiting period—that is religions must be present for a minimum number of years in the country before they can register. Austria, Belgium, Germany and Sweden all have both of these requirements. For example, a religion in Belgium must fulfill five poorly defined criteria to register. These include having a ‘sufficient’ number of members, having a structure or hierarchy, offering a ‘social value’ to the public, existing in the country for a ‘long period’ of time, and abiding by state laws. Groups must apply to the Ministry of Justice, which conducts a time consuming comprehensive review before submitting its recommendation to Parliament. However, once this process is completed registration is rarely denied.21 40% of Christian democracies limit the ability of minority religions to build, lease, or repair places of worship. As noted above, in some cases this applies to unregistered religions. This type of discrimination is increasing. Between 1990 and 2008, Austria, Bulgaria, Spain and Switzerland all either began engaging in this type of restriction or increased the intensity of existing restrictions. In Austria, for example, several provinces have used zoning laws to restrict the building of Mosques or Minaret's.22 In Switzerland, the codings, which end in 2008, predate the national law against Minarets passed by referendum in 2009 and, like Austria, are due to the use of local zoning laws to deny permits for building Mosques or Minarets.23 This 20 US Department of State Report on Religious Freedom, 2008, 2009. Online: http://www.state.gov/g/drl/rls/irf/2009/71383.htm 21 U.S Department of State International Religious Freedom Report 2002,2003,2004,2005,2006,2007,2008 Online: http://www.state.gov/g/drl/rls/irf/2008/108437.htm 22 Reuters (27.07.2007) (via. Human Rights without Frontiers website) “Austria’s Haider Says to Ban Mosque Building” Website: http://www.hrwf.net; BBC Monitoring Europe “Austrian People's Party opposes construction of mosques, immigration” July 9, 2007 23 23 US State Department Report on Human Rights, 2005, 2006, 2007, 2008. Online: http://www.state.gov/g/drl/rls/hrrpt/2006/78842.htm; The Independent, “Switzerland: Europe’s Heart of Darkness?”, September 7, 2007; Human Rights Without Frontiers, “Swiss Nationalists Force Referendum on Minaret Ban”, by Elaine Engeler,July 8, 2008. Online: www.hrwf.net. 13 יC pattern indicates the possibility that national government policies of restrictions on religious minorities can be foreshadowed by the actions of local and regional governments. 35% of these countries place limitations on the entry of foreign clergy and missionaries. This type of law is becoming increasingly prominent with four countries, Costa Rica, Denmark, Panama, and the Ukraine, either beginning or increasing the intensity of these restrictions between 1990 and 2008. While this practice is most prevalent in former Soviet Christian democracies, it is present in all categories of states in this study. These restrictions are usually minor. In the Ukraine, for example, the law limits permissible activities by clergy from "nonnative" religions. However, in practice, there have been few reported cases of this law being enforced. Though, in 2007 Mormons claimed that a local government in the Rivne Oblast region banned preaching outside of their places of worship.24 In 2004 Denmark passed a more serious set of restrictions known as the "Imam Law." The law is widely believed to be targeted against Muslim clergy but restricts all minority religions. It limits the number of residence visas for foreign clergy to numbers proportional to the size of the religious community. Visas are only granted to those who are selffinanced, associated with a recognized religion and who can demonstrate possession of a relevant background for religious work. Visas may be denied if there is “reason to believe the foreigner will be a threat to public safety, security, public order, health, decency or other people's rights and duties." 25 32.5% of these countries limit the access of chaplains from minority religions to places where majority religion chaplains have access. In Peru, for example, the law states that the military may hire only Catholic clergy as chaplains, and Catholicism is the only recognized religion of the military. In addition, a 1999 Government compelled members of the armed forces and the police, as well as their civilian coworkers and relatives, to participate in Catholic services.26 30% of these countries have anti-sect laws which declare some sects dangerous and require monitoring and perhaps restrictions on these religions. This type of law is rapidly increasing with Belgium, France, Germany, Hungary, Lithuania, Poland, and Sweden all adding this type of law or practice between 1990 and 2008. Both France and Belgium began this practice after mass suicides by cults. They also both maintain lists of cults. These lists include groups may consider to be "cults" or "sects" such as the Church of Scientology, the Unification Church, and Jehovah’s Witnesses. However, both lists also include groups considered more mainstream elsewhere. In France these include Mormons, Seventh Day Adventists, and Pentecostals.27 In Belgium these include Seventh-Day Adventists, Zen Buddhists, Mormons, Hassidic Jews and the YWCA. In France the government created the “Inter-ministerial Mission in the Fight against sects/cults” (MILS) in 1998, which was dissolved in 2002 and replaced in 2003 by a similar organization called MIVILUDES. Both organizations have been accused of abuses of religious freedom. (Fox, 2008; 24 .S Department of State International Religious Freedom Report 2002,2003,2004,2005,2006,2007,2008 Online: http://www.state.gov/g/drl/rls/irf/2008/108437.htm 25 State Department Report on Religious Freedom, 2006 Online: http://www.state.gov/g/drl/rls/irf/2006/71377.htm, The Times (London), “Denmark to Curb Muslim Preachers” by Anthony Browne, February 19, 2004 26 US Department of State, International Religious Freedom Report, 2003, 2004,2005,2006,2007,2008. Online: http://www.state.gov/g/drl/rls/irf/2003/24504.htm 27 An English translation of this report is available at http://www.cftf.com/french/Les_Sectes_en_France/cults.html. 14 יC Grim & Finke, 2011: 33-36; Kuru, 2009)28 In Belgium, discrimination against groups on the list can include police surveillance, loss of jobs, denial of citizenship, and loss of child custody.29 Thus both the Belgian and French policies seem to be targeted against groups which are small and different rather than against dangerous groups and groups in the list can potentially suffer from serious limitations of religious freedom. 25% of these countries engage in anti-religious propaganda against at least some minority religions. This is often directed at those perceived as dangerous "sects" or "cults." An extreme example of this is Germany's campaign against the Church of Scientology. In addition to numerous other restrictions and forms of harassment against Scientologists, German state and federal authorities routinely warn against the "dangers of Scientology" in both print and electronic media. For example, several German states publish derogatory pamphlets about Scientology and other religious ‘sects.’30 22.5% of Christian democracies restricted the wearing of religious symbols or clothing. This type of restriction is targeted almost exclusively against Muslims and is increasing significantly with Austria, Belgium, Bulgaria, Germany, Norway, and Switzerland all adding this type of restriction between 1990 and 2008. In nearly all cases these are restrictions by local governments on the wearing of headscarves by Muslim women who are public employees or teachers. For example, in 2003 Federal Constitutional court of Germany acknowledged that states could ban headscarves. (Cesari 2009) By the end of 2008 at least eight of Germany's states had enacted such a ban.31 France's 2004 law is not included in this list because, as noted above, while also likely targeted against Muslim women, it explicitly limits the wearing of all religious symbols in public schools and is applied to all religions in the country. All of these other countries limit Muslim religious expression exclusively. In another rapidly increasing form of restriction, 22.5% of these countries engage in surveillance of minority religious activities. Between 1990 and 2008, Belgium, France, Trinidad and Tobago, and the UK all began this type of activity. This surveillance is primarily against Muslims in the post 9/11 era and against those 28 US Department of State Religious Freedom Report, 2003, 2004, 2005, 2006 . Online: http://www.state.gov/g/drl/irf/rpt/, BBC News Europe, “France Moves to Outlaw Cults”, June 22, 2000, ReligiousTolerance.Org, Ontario Consultants on Religious Tolerance, Online: http://www.religioustolerance.org/rt_franc.htm, Human Rights Without Frontiers, “Public Controversy About Miviludes”, October 17, 2007. Online: www.hrwf.net, Human Rights Without Frontiers, “Religious Discrimination in France : CAP submission regarding the appointment of Mr. Georges Fenech as President of MIVILUDES” October 7, 2008. Online: www.hrwf.net, MIVILUDES 2006 Report to the Prime Minister, Online: www.miviludes.gouv.fr/IMG/pdf/Report_Miviludes_2006.pdf. 29 International Coalition for Religious Freedom, World Reports Online: http://www.religiousfreedom.com/; Human Rights Without Frontiers “The Institute on Religion and Public Policy Denounces Defamation of Religion in Belgium at the UN” Online: www.hrwf.net; Human Rights Without Frontiers, “Defamation of Religions in Belgium”; International Christian Concern, “Institute Report to UN Details Systematic Religious Discrimination in Belgium” online: www.persecution.org. 30 US State Department Report on Religious Freedom, 2006, 2007,2008. Online; http://www.state.gov/g/drl/rls/irf/2006/127312.htm ; Spiegel, “Munich Closes Scientologist Day-Care Center”, February 26, 2008 31 European Studies on Religion and State Interaction, “State and Church in Germany”, January 2008. Online: http://www.euresisnet.eu/Pages/ReligionAndState/GERMANY.aspx, “Germany’s Hijab Ban Discriminatory: HRW”, February 26, 2009, DPA, “German court Upholds Headscarf Ban”, December 10, 2007, http://www.islamonline.net/servlet/Satellite?c=Article_C&cid=1235628698092&pagename=ZoneEnglish-News/NWELayout 15 יC perceived as "sects" or "cults." This variable was only coded if the surveillance was of religious activities and beyond what would be expected for basic security concerns. This widespread, serious, and increasing religious discrimination in Christian democracies clearly violates all conceptions of SRAS. The secularist-laicist doctrine accepts the maintenance of a secular public space but would mandate the same restrictions on all religions, not restrictions focused on minority religions. The neutral political concern and exclusion of ideals models also could tolerate some forms of restrictions placed on all religions but targeting only minority religions violates their conception of equality. The absolute SRAS model tolerates no government interference in religion at all. The only category of states with relatively low levels of religious discrimination among Christian democracies are those in Latin America and Asia. Figure 1 presents a graphic representation of these 40 countries' scores on religious legislation and religious discrimination. That very few states are even close to 0-points on the x-y axis further demonstrates the lack of SRAS in Christian democracies. [Figure 1 about here] Conclusions The results of this study show that, at a minimum, a large majority of Christian democracies, and perhaps all of them, engage in levels of religious legislation and support for religion sufficiently high that they violate any reasonable notion of SRAS. In 2008, 75% of them supported some religions over others and all of them had at least some religious legislation. In addition 80% of these states place at least some restrictions on the religious freedom of religious minorities. Based on this, few democratic states meet any of the four standards for SRAS. Neutral political concern demands equality across religions. Thus, it requires no religions discrimination (restrictions placed on minorities not placed on the majority religion) and that should the government support religion, it must do so equally for all religions. Only Canada, New Zealand, and Uruguay meet this standard. Exclusion of ideals similarly demands neutrality, but neutrality of intent rather than neutrality in the outcome. Thus it is difficult to measure but a clear level of non-neutrality in outcome can arguably reflect an absence of neutrality in intent so the results for exclusion of ideals are, in practice, the same as those for neutral political concern. No states meet the absolute SRAS standard, as any religious legislation or religious discrimination would violate this model. The secularism-laicism model also prohibits support for religion and religious discrimination so no state meets this standard in a strict sense. When looking at religious legislation and support for religion alone it is possible to argue that many or even all of these states meet the minimal standards for democracy set out by Mazie (2004; 2006), Driessen (2010), and Marquand & Nettler (2000). These standards allow support for religion and even a preference for certain religions is acceptable as long as a religion is not made mandatory, religious actors do not have a veto power over government decisions, and religious freedom is maintained for minorities. There is very little evidence of Christian democracies violating the first two elements of this standard. With the possible exception of antiabortion laws, few Christian democracies make any aspect of Christianity mandatory. Blasphemy laws exist and are likely a violation of the freedom of speech and expression, but a ban on insulting Christianity does not prevent one from practicing 16 יC another religion. Religious education in public schools is common, but there are no instances of anyone being forced to take classes in a religion other than their own. However, even these standards are not met by most Christian democracies when we add in the element of religious discrimination which only eight (20%) of these states avoid. Even if we create a more lenient standard which allows some religious discrimination and legislation, based on the argument that states can violate standards in small ways and still hold to their spirit, few democratic states meet this standard. If we set very lenient standards of a score of 3 or below on religious discrimination, a score of 5 or below on religious legislation, and that the state not declare an official religion or support some religions more than others only eight of the 40 countries in this study qualify: Australia, Brazil, Italy, Jamaica, The Netherlands, New Zealand, Slovenia, the US, and Uruguay. Thus, there is arguably no standard for SRAS sufficiently lenient to allow for a majority of Christian democracies to meet that standard which also would even minimally resemble any recognizable conception of SRAS. In fact, no such standard allows for more than 20% of democratic Christian countries to be considered to have SRAS. The debate over whether SRAS is an essential element of liberal democracy is one that receives much attention when discussing theory. However, when viewing the facts on the ground, there is little room for debate. An overwhelming majority of Christian democracies have substantial levels of religious legislation and give de-jure and de-facto preferences to a single religion or a few religions. This finding is consistent across world regions and denominations of Christianity. Most of these states, especially outside of Latin America and Asia, also engage in religious discrimination against minority religions. As Christian democracies constitute the group most expected to maintain state neutrality on the issue of religion, these results require a recognition that these ideals are rarely, if ever, achieved in practice. This lack of observance of these ideals arguably reaches the point where state practice disproves the relevance of these ideals. That is, since the countries in this study are among the most democratic in the world, these results also show that state support for religion and democratic government can be compatible. While it is not possible to argue that democracy and discrimination against minorities are compatible, the evidence shows that it is possible for a state to be engaged in such discrimination and still be considered by many to be a liberal democracy. The only other possible argument to explain these results is that most states considered liberal democracies are, in fact, not liberal democracies. Given this, many theoretical and ideological conceptions of the role of religion in democracies, including Western and other Christian democracies need to be reevaluated in the face of reality. Consequently, future research agendas should include the following: (1) An examination of how much deviation from the ideal of religious freedom is, in practice, acceptable in democracies and under what circumstances. (2) Developing a model of state support for religion in democracies that reflects the reality of ubiquitous state support as well as a theoretical and perhaps ideological justification for this model. Such a model would include how religion can contribute to democracy, as argued by de Tocqueville, as well as what forms of government support for religion are compatible with democracy and which forms of government support are not compatible. As discussed above, Mazie (2004; 2006), Driessen (2010), and Marquand & Nettler (2000), among others, have begun developing such a model but tend to focus on a limited number of cases. A more 17 יC comprehensive model would take into account the wide variety of government support for religion revealed in this study. 18 יC Bibliography Bader, Veit “Religious Pluralism: Secularism or Priority for Democracy” Political Theory, 27 (5), 1999, 597-633. Casanova, Jose “The Secular and Secularisms” Social Research, 76 (4), 2009, 10491066. Cesari, Jocelyne. When Islam and Democracy meet: Muslims in Europe and in the United States. Palgrave; Macmillan, 2004. Cingranelli, David L., and David L. Richards “The Cingranelli-Richards (CIRI) Human Rights Database.” <http://ciri.binghamton.edu> 1 July 2006. Demerath, N.J. III Crossing the Gods: World Religions and Worldly Politics, New Jersey: Rutgers University Press, 2001. Driessen, Michael D. P. “Religion. State and Democracy: Analyzing Two Dimensions of Chrch-State Arrangements” Politics and Religion, 3 (1), 2010, 55-80. Durham, W. Cole Jr. “Perspectives on Religious Liberty: A Comparative Framework” in John D. van der Vyver & John Witte Jr. Religious Human Rights in Global Perspective: Legal Perspectives, Boston: Martinus Njhoff, 1996. 1-44. Esbeck, Carl H. “A Typology of Church-State Relations in American Thought” Religion and Public Education, 15 (1), 1988, 43-50. Fox, Jonathan “Do Democracies Have Separation of Religion and State?” Canadian Journal of Political Science, 40 (01), 2007, 1-25. Fox, Jonathan A World Survey of Religion and the State, New York: Cambridge University Press, 2008. Fradkin, Hillel “Does Democracy Need Religion?” Journal of Democracy 11 (1), 2000, 87-94. Greenawalt, Kent Religious Convictions and Political Choice, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1988. Grim, Brian J. & Roger Finke “International Religion Indexes: Government Regulation, Government Favoritism, and Social Regulation of Religion” Interdisciplinary Journal of Research on Religion, 2 (1), 2006, 1-40. Grim, Brian J. & Roger Finke The Price of Freedom Denied, New York: Cambridge University Press, 2011. Haynes, Jeff “Religion, Secularisation, and Politics: A Postmodern Conspectus” Third World Quarterly, 18 (4), 1997, 709-728. 19 יC Horowitz, Donald L. Ethnic Groups in Conflict, Berkeley: University. of California Press, 1985. Hurd, Elizabeth S. “The Political Authority of Secularism in International Relations” European Journal of International Relations, 10 (2), 2004a, 235-262. Hurd, Elizabeth S. “The International Politics of Secularism: US Foreign Policy and the Islamic Republic of Iran” Alternatives, 29 (2), 2004b, 115-138. Jaggers, Keith and Ted R. Gurr “Tracking Democracy's Third Wave with the Polity III Data” Journal of Peace Research, 32, (4), 1995, 469-482. Keane, John “Secularism?” The Political Quarterly, 71 (Supplement 1), 2000, 5-19. Kuru, Ahmet T. “Passive and Assertive Secularism: Historical Conditions, Ideological Struggles, and State Policies Toward Religion” World Politics, 59 (4), 2006, 568-594. Laycock, Douglass “The Underlying Unity of Separation and Neutrality” Emory Law Journal, 46, 1997, 43-75. Lijphart, Arend, Democracy in Plural Societies, New Haven: Yale University Press, 1997. Madeley, John TS. “European Liberal Democracy and the Principle of State Religious Neutrality” West European Politics, 26 (1), 2003, 1-22. Mazie, Steven V. “Rethinking Religious Establishment and Liberal Democracy: Lessons From Israel” Brandywine Review of Faith and International Affairs, 2 (2), 2004, 3-12. Mazie, Steven V. Israel's Higher Law: Religion and Liberal Democracy in the Jewish State New York: Lexington, 2006. Mill, John S. “Considerations on Representative Government” in John S. Mill, Utilitarianism, Liberty, and Representative Government, New York: E. P. Dutton, 1951. (Originally published in 1861.) Rawles, John Political Liberalism, New York: Columbia University Press, 1993. Shah, Timothy S. “Making the Christian World Safe for Liberalism: From Grotius to Rawls” The Political Quarterly, 71 (s1), 2000, 121-139. Stepan, Alfred “Religion, Democracy, and the ‘Twin Tolerations’” Journal of Democracy, 11 (4), 2000, 37-56. Witte, John Jr. “Facts and Fictions About the History of Separation of Church and State” Journal of Church and State, 48 (1), 2006, 15-45. 20 יC Table 1: Models for Separation of Religion and State and for Acceptable Support for Religion in Democracies SecularismLaicism Absolute SRAS State support for religion? No No State restrictions on religion? Yes, in public sphere and if applied equally Yes, if applied equally Restrictions on religion in public discourse and expression? Neutral political concern Yes, if applied equally Exclusion of ideals Acceptable Support for Religion Yes, as long as there is no ideological preference for any religion. No Yes, if applied equally Yes, as long as there is no ideological preference for any religion. Yes, as long as religion isn’t mandatory and there is no religious veto on state policy No No Yes, if applied equally. Yes, as long as there is no ideological preference for any religion. 21 No יC Table 2: State Support for Religion Western Democ. By Region Former Soviet 1990 (or earliest) Official Religion Single Religion Preferred Some Religions Preferred Equal Support for All Religions No or minimal support 28.6% 19.0% 23.8% 4.8% 23.8% 0.0% 25.0% 62.5% 12.5% 0.0% 18.2% 27.3% 18.2% 27.3% 9.1% 10.0% 35.0% 30.0% 10.0% 10.0% 30.0% 5.0% 30.0% 15.0% 20% 20.0% 22.5% 30.0% 12.5% 15% 2008 Official Religion Single Religion Preferred Some Religions Preferred Equal Support for All Religions No or minimal SUPPORT 23.8% 19.0% 28.5% 4.8% 23.8% 0.0% 25.0% 75.0% 0.0% 0.0% 18.2% 27.3% 18.2% 27.3% 9.1% 10.0% 40.0% 30.0% 10.0% 10.0% 25.0% 5.0% 40.0% 10.0% 20% 17.5% 22.5% 35.0% 10.0% 15.0% 21 8 11 20 20 40 N 22 Latin Amer. & Asia By Religion Catholic Other Christian All יC Table 3: Average Levels of Religious Legislation N Mean % with this number or less types 1990 or Earliest 2008 3 5 9 3 5 10.0% 35.0% 75.0% 10.0% 32.5% 9 75.0% All Cases 40 1990 7.10 2008 7.35 By Official Religion Official Religion No official Religion Sweden* 7 32 1 10.29c 6.25c 12.00 10.14b 6.62ab 11.00 0.0% 12.5% -- 0.0% 43.8% -- 42.9% 87.5% -- 0.0% 12.5% -- 0.0% 40.6% -- 42.9% 87.5% -- Countries with No Official religion* By Region West. Democracies Former Soviet Latin Amer. & Asia 15 8 9 6.40 7.38 5.00 6.60 8.25 5.22 13.3% 12.5% 11.1% 46.7% 25.0% 55.5% 86.7% 75.0% 100.0% 6.7% 12.5% 22.2% 40.0% 25.0% 55.6% 86.7% 75.0% 11.1% By Religion Catholic 18 6.00 6.50a 5.6% 44.4% 94.4% 11.1% 38.9% Other Christian 14 6.57 6.79 21.4% 42.9% 78.6% 14.3% 42.9% *Sweden had an official religion in 1990 and none in 2008 so it is treated separately. It is not included in countries with no official religion. a = Significance (t-test) between marked value and value for 1990 < .05 b = Significance (t-test) between marked value and other values in same row < .01 c = Significance (t-test) between marked value and other values in same row < .001 23 94.4% 78.6% יC Table 4: Specific Types of Religious Legislation in 2008 Types of Religious Law* All Cases Official Relig. No Official Relig All cases West. Dems Former Soviet Lat. Amer. & Asia 11.1% 44.4% 11.1% 0.0% 0.0% 0.0% 0.0% 88.9% 0.0% 44.4% 0.0% 0.0% 0.0% 11.1% 0.0% 11.1% 22.2% 0.0% 11.1% 11.1% 11.1% 11.1% Cath. Personal status defined by religion or clergy 7.5% 14.3% 6.1% 6.3% 0.0% 5.6% Religious marriages given automatic civil recognition 37.5% 57.1% 33.3% 31.3% 25.0% 38.9% Homosexuality illegal 2.5% 0.0% 3.0% 0.0% 0.0% 0.0% Blasphemy laws: protect majority religion 17.5% 42.9% 12.1% 12.5% 25.0% 22.2% Blasphemy laws: protect minority religion 10.0% 14.3% 9.1% 12.5% 12.5% 16.7% Businesses closed on holidays, Sabbath, etc. 15.0% 28.6% 12.1% 25.0% 0.0% 0.0% Other restrictions: during holidays, Sabbath, etc. 7.5% 0.0% 9.1% 18.8% 0.0% 0.0% Religious education in public schools 87.5% 100.0% 87.5% 87.5% 75.0% 83.3% Official prayers in public schools 15.0% 42.9% 9.1% 18.8% 0.0% 0.0% Fund religious schools: primary or secondary 65.0% 71.4% 63.6% 75.0% 62.5% 55.6% Fund seminary schools 12.5% 28.6% 9.1% 0.0% 37.5% 11.1% Fund religious education in university 17.5% 28.6% 15.2% 25.0% 12.5% 0.0% Public schools segregated by religion 5.0% 0.0% 6.1% 12.5% 0.0% 5.6% Fund religious charitable organizations 20.0% 0.0% 24.2% 25.0% 37.5% 16.7% Government collects religious tax 27.5% 28.6% 27.3% 50.0% 12.5% 33.3% Salaries positions of funding for clergy (not chaplain) 45.0% 57.1% 42.4% 50.0% 62.5% 44.4% General monetary grants to religious organizations 40.0% 71.4% 33.3% 31.3% 50.0% 27.8% Fund, maintain, or repair, religious sites 30.0% 28.6% 30.3% 31.3% 62.5% 16.7% Free air time on public television or radio 22.5% 14.3% 24.2% 18.8% 50.0% 22.2% Fund religious pilgrimages such as Haj 2.5% 0.0% 3.0% 0.0% 0.0% 5.6% Other funding for religion 22.5% 28.6% 21.2% 18.8% 37.5% 11.1% Religious leaders given diplomatic status or 5.0% 0.0% 6.1% 0.0% 12.5% 11.1% immunity Official government religious ministry/department 47.5% 42.9% 48.5% 25.0% 100.0% 44.4% 55.6% Religious police force to enforce religious laws 2.5% 0.0% 3.0 0.0% 12.5% 0.0% 0.0% Gvt. official given automatic religious position 2.5% 14.3% 0.0% 0.0% 0.0% 0.0% 0.0% Religious officials given automatic gvt. Position 2.5% 14.3% 0.0% 0.0% 0.0% 0.0% 0.0% Religious criteria for holding public office 7.5% 42.9% 0.0% 0.0% 0.0% 0.0% 0.0% Rel. courts: jurisdiction over family law/inheritance 5.0% 14.3% 3.0% 0.0% 0.0% 11.1% 5.6% Rel. courts: jurisdiction over other matters 0.0% 0.0% 0.0% 0.0% 0.0% 0.0% 0.0% Seats in legislature or cabinet granted along rel. lines 5.0% 14.3% 3.0% 6.3% 0.0% 0.0% 0.0% Prohibitive restrictions on abortion. 45.0% 42.9% 45.5% 31.3% 12/5% 100.0% 61.1% Religious symbols on the state’s flag. 20.0% 71.4% 9.1% 12.5% 12.5% 0.0% 5.6% Religion listed on identity cards or gvt. Documents 2.5% 0.0% 3.0% 0.0% 0.0% 11.1% 5.6% Special registration process for religions. 67.5% 71.4% 66.7% 56.3% 100.0% 55.6% 72.2% Other restrictions or religious laws 12.5% 28.6% 9.1% 6.3% 12.5% 11.1% 16.7% *= The following types of religious law are not included on the table because no countries are coded as positive: Dietary laws; Restrictions: sale of alcoholic beverages; Restrictions: interfaith marriages; Laws of inheritance defined by religion; Religious definitions of or punishment for crimes; Charging interest is illegal or significantly restricted; Women may not go out in public unescorted; Restrictions: the public dress of women; Other dress requirements in public; Restrictions: unmarried heterosexual couples; Restrictions: conversions from dominant religion; Censorship 'anti-religious' publications; Restrictions: public music or dancing; Female testimony in court given less weight; Restrictions: access to birth control; Restrictions on women not listed above. 24 Other Christ. 6.7% 26.7% 6.7% 12.1% 0.0% 26.7% 20.0% 86.7% 20.0% 73.3% 6.7% 33.3% 6.7% 33.3% 20.0% 40.0% 40.0% 46.7% 26.7% 0.0% 33.3% 0.0% 40.0% 6.7% 0.0% 0.0% 0.0% 0.0% 0.0% 6.7% 26.7% 13.3% 0.0% 60.0% 0.0% יC Table 5: Average Levels of Religious Discrimination N Mean All Cases 40 1990 4.48 2008 6.00b % with this number of less types 1990 or Earliest 2008 0 3 9 0 3 20.0% 52.5% 82.5% 20.0% 45.0% By Official Religion Official Religion No official Religion Sweden* 7 32 1 5.86 4.16 5 6.86 5.69b 10 0.0% 25.0% -- 28.6% 59.4% -- 85.7% 81.3% -- 0.0% 25.0% -- 28.6% 53.1% -- 85.7% 78.1% -- Countries with No Official religion* By Region West. Democracies Former Soviet Latin Amer. & Asia 15 8 9 4.80 5.88 1.94c 6.80a 7.85 2.20c 26.7% 12.5% 3.33% 53.3% 37.5% 8.89% 80.0% 62.5% 100.0% 26.7% 12.5% 3.33% 53.3% 25.0% 8.89% 80.0% 62.5% 100.0% By Religion Catholic 18 3.67 5.22a 27.8% 61.1% 88.9% 27.8% 50.0% Other Christian 14 4.79 6.29 21.4% 57.1% 71.4% 21.4% 57.1% *Sweden had an official religion in 1990 and none in 2008 so it is treated separately. It is not included in countries with no official religion. a = Significance (t-test) between marked value and value for 1990 < .05 a = Significance (t-test) between marked value and value for 1990 < .01 c = Significance (t-test) between marked value and other values in same row < .01 25 9 77.5% 77.8% 78.6% יC Table 6: Specific Types of Religious Discrimination in 2008 Types of Religious Discrimination* All Cases Official Relig. No Official Relig All cases West. Dems Former Soviet Lat. Amer. & Asia 0.0% Cath. Restrictions: public observance of religious services, 10.0% 14.3% 9.1% 12.5% 12.5% 11.1% festivals and/or holidays, including the Sabbath Restrictions: build/lease/repair places of worship. 40.0% 42.9% 39.4% 50.0% 62.5% 0.0% 33.3% Restrictions: access to existing places or worship. 7.5% 28.6% 3.0% 0.0% 12.5% 0.0% 0.0% Restrictions: formal religious organizations. 15.0% 0.0% 18.2% 18.7% 25.0% 11.1% 22.2% Restrictions: religious schools or education. 10.0% 28.6% 6.1% 12.5% 0.0% 0.0% 0.0% Restrictions: make/obtain religious materials. 7.5% 14.3% 6.1% 12.5% 0.0% 0.0% 0.0% Mandatory education in the majority religion 10.0% 28.6% 6.1% 6.3% 0.0% 0.0% 5.6% Arrest/continued detention/ severe official 17.5% 14.3% 18.2% 31.2% 12.5% 0.0% 22.2% harassment for activities other than proselytizing Surveillance of rel. activities not placed on Majority. 22.5% 14.3% 24.2% 25.0% 37.5% 11.1% 33.3% Restrictions: publish/disseminate rel. publications. 7.5% 0.0% 9.1% 12.5% 12.5% 0.0% 00.0% Restrictions: religious personal status laws (marriage, 12.5% 28.6% 9.1% 18.7% 0.0% 0.0% 0.0% divorce, and burial) Restrictions: wearing of rel. symbols or clothing. 22.5% 14.3% 24.2% 31.2% 25.0% 11.1% 11.1% Restrictions: ordination of and/or access to clergy. 7.5% 14.3% 6.1% 6.3% 12.5% 0.0% 0.0% Restrictions: proselytizing by permanent residents of 15.0% 28.6% 12.1% 12.5% 12.5% 11.1% 5.6% state to members of the majority religion. Restrictions: proselytizing by permanent residents of 12.5% 0.0% 15.2% 12.5% 12.5% 22.2% 11.1% state to members of minority religions. Restrictions: proselytizing by foreign 35.0% 71.4% 27.3% 25.0% 27.5% 22.2% 27.8% clergy/missionaries. Minority religions must register to be legal or receive 52.5% 71.4% 48.5% 50.0% 75.0% 22.2% 44.4% special tax status. Custody of children granted based on religion. 2.5% 0.0% 3.0% 6.3% 0.0% 0.0% 5.6% Restricted access of minority clergy to hospitals, 32.5% 42.9% 30.3% 31.2% 50.0% 11.1% 27.8% jails, military bases, etc. Legal policy declaring some minorities dangerous 30.0% 14.3% 33.3% 43.7% 50.0% 0.0% 44.4% cults/sects. Anti-religious propaganda in official or semi-official 25.0% 14.3% 27.3% 31.2% 50.0% 0.0% 27.8% government publications. Other restrictions. 17.5% 0.0% 21.2% 37.5% 0.0% 11.1% 22.2% *= The following types of religious discrimination are not included on the table because no countries are coded as positive: Restrictions: private observance of religious services, festivals and/or holidays, including the Sabbath; Forced observance: religious laws of another group; Restrictions: import religious publications; Restrictions: conversion to minority religions; Forced renunciation of faith by recent converts to minority religions; Forced conversions of people who were never members of the majority religion; Efforts/campaigns to convert members of minority rel. to the majority rel. not involving force; Restrictions: religious publications for personal use. 26 Other Christ. 6.7% 46.7% 6.7% 13.7% 13.3% 13.3% 6.7% 13.3% 13.3% 20.0% 20.0% 40.0% 14.7% 20.0% 20% 26.7% 53.3% 0.0% 33.3% 20.0% 26.7% 20.0% יC Figure 1: Scatterplot of Religious Legislation and Religious Discrimination in 2008 27