These developments in the former GDR were, however, not typical

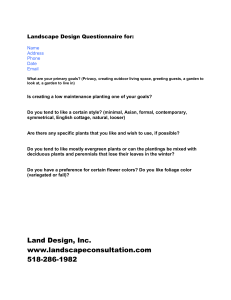

advertisement

ВІСНИК ЛЬВІВ. УН-ТУ Серія географічна. 2004. Вип.31. С. 56–65 VISNYK LVIV UNIV Ser.Geogr. 2004.№31. Р. 56–65 УДК 911:2 ASSESSMENT AND CLASSIFICATION OF LANDSCAPES – ADOPTING AND DEVELOPING NEEF’S LANDSCAPE RESEARCH IN SAXONY / GERMANY O. Bastian Saxon Academy of Sciences, Dresden, Germany D-01097 Dresden, Olaf.Bastian@mailbox.tu-dresden.de The scientific concept of landscape research essentially coined by the German geographer E. Neef, proves to be a key for the analysis, diagnosis and prognosis of the human environment, and it is very important for modern landscape planning. A brief survey of the historical development shows varying paradigms in the definition and investigation of landscape. Especially such items like bottom-up landscape classifications, potentials of nature / landscape functions, and the problems of landscape visions (leitbilder) are special contributions of the Dresden working group “Natural balance and regional characteristics” of the Saxon Academy of Sciences. Regarding practical application, complex, complementary and transdisciplinary views on landscapes become more and more important. Key words: landscape, landscape ecology, geography, spatial units, landscape planning Landscape research has a long tradition in Germany. After Alexander von Humboldt used the term landscape 200 years ago in the sense of the „total character of a selected part of the earth“ (Totalcharakter von Erdgegenden), research on landscape became popular as a branch of geography. Especially the holistic view on landscape, which was mainly supported by Troll, Paffen, Schmithüsen and Neef in the beginning of landscape research, was an innovation offering a useful approach to solve environmental problems which were realized by scientists and the general public more and more. Among others, the ideas and principles developed by the German geographer Ernst Neef and his scientific school in Saxony have been important not only for shaping geography, landscape research and landscape ecology as basic sciences, they also show permanently increasing importance for practical purposes such as environmentally-friendly land use, landscape planning, and sustainable development, generally. The paper will give a brief survey of some theoretical and practical aspects of landscape research and landscape planning influenced by the ideas and approaches of E. Neef and his scientific school. Landscape research: Aspects of the historical development. According to Neef [31] landscape is a part of the earth’s surface with “a uniform structure and functional pattern”, both in its appearance and constituent components. The components or ‘geofactors’ to be identified are relief, soil, climate, water balance, flora, fauna, people and their creations and artefacts in the landscape (Fig. 1). Appearance also included ideas about spatial position. From the outset, beginning with A. von Humboldt, landscape was intended as an holistic idea. Thus 1850, Rosenkranz [in 42] defined landscapes in terms of the hierarchically organized local systems made up of all the kingdoms of nature. Such ________________________ © Bastian O., 2004 ASSESSMENT AND CLASSIFICATION OF LANDSCAPE ... 57 ideas reflected similar ideas being developed across Central and Eastern Europe at this time, and which continue to be expressed by more recent scholars. Apart from Neef, also (other) contemporary authors have stressed the fact that landscape is not only the sum of separate geofactors, but also represents the integration of factors into a geographical complex or ‘geosystem’ [20]. For them, the landscape ecosystem is defined by the spatial pattern of abiotic, biotic and anthropogenic components which form a unified functional entity and which serves as the environment for people. However, one has to understand that ‘landscape’ is a term with manifold connotations, and therefore has no single and final definition. A lot of reasons for discussion in the German geography gave the description of the term in a sense of landscape as ‘Wesenheiten’ (intrinsic entities) instead of purpose-based spatial constructs. People were trying to grasp the character of a landscape (‘Wesen der Landschaft’ [35]), which was to be understood as a real existing organic ‘Gestalt-complex’ – as entity – which with the help of the experienced view of the geographer could be made out and analysed. Some authors such as Hard [21] defined landscape as “a primarily aesthetic phenomenon, closer to the eyes than to the mind, more related to the heart, the soul, the moods than to the intellect.” But also the focus on cultural landscapes which has become important during recent years within landscape research [e.g., 10, 12, 46] refers to a more comprehensive understanding of landscapes. Today, the understanding of landscape tends to a relativized, complementary view: on the one side landscapes are depending on scientific law and principles, on the other side they are artificial constructs of our mind following complementarity which was supposed by N. Bohr (at the beginning of the last century) to be a general dialectic principle in scientific research, and that was adopted to geography and landscape research in the 1980s by Buchheim [11] and Neef [34]. The meaning of complementarity in landscape research is the parallelism of independent research disciplines. This is not a scientific shortcoming, but a necessity in the investigation of geographical (landscape) complexes. Landscape as a very complicated phenomenon is analysed and described from various points of view by different scientific approaches and disciplines. To gain a comprehensive picture of the landscape, all the manifold ecological, social, cultural, psychological aspects must be taken into consideration [4]. This is obvious especially in the field of landscape delimitation and classification. Traditionally, the geographer’s approach to landscape can generally be described as ‘integrative’ rather than ‘sectoral’ [e.g., 23]. This characteristic is, probably, mostly stressed in the holistic view of landscape developed by workers from the former GDR and from Eastern Europe. Such approaches were stimulated in recent years by work such as that by Haase et al. [17], Mannsfeld & Neumeister [27], Zepp & Müller [47] and Krönert et al. [22]. Using Neef’s formulation of the landscape concept, involving the integration of nature, humans, and society in a single system, both physical and human geography approaches could be combined. These developments in the former GDR were, however, not typical of those in other parts of the country were reductionist views in the environmental sciences and geography tended to dominate. In geography the term landscape was pushed into the background, and it lost its crucial position in the second half of the last century. In the 1970s Neef [33] criticised the ‘trend’ of defining geography as a special kind of social science, along with the tendency to separate the physical and human sides of the discipline. Mannsfeld [26] has also identified the issue of geography developing towards a specified sectoral science at the expense of its more traditional integrative approach. О. Bastian 58 transformation of radiation energy and heat through physical processes transformation of heat energy through biochemical processes transformation of water air transformation of gaseous and liquid inorganic matter fauna air near ground flora relief / ground surface edaphon humus / soil transformation of organic matter transformation of clastic inorganic matter bedrock processes of same direction epidermis: two dimensional compartment of the geomorphosphere landscape component Figure 1. Model of vertical landscape structure and processes [25, modified after 39]. Only recently [40] the interest in more holistic approaches is being reawakened in geography, planning and ecology, and the term ‘landscape’ is starting to coming back into research, partly as the result of the growth of landscape ecology as a distinct research focus [1, 30, 4, 37], and partly because the term ‘landscape’ has been taken up by other disciplines, and particularly by those which propose more transdisciplinary approaches. Landscape ecology gave very important stimuli to landscape research. The term ‘landscape ecology’ was created and defined by C. Troll [45] as follows: “Studium des gesamten, in einem bestimmten Landschaftsausschnitt herrschenden komplexen Wirkungsgefüges zwischen den Lebensgemeinschaften (Biozönosen) und ihren Umweltbedingungen. Dieses äußerst sich räumlich in einem bestimmten Verbreitungsmuster ASSESSMENT AND CLASSIFICATION OF LANDSCAPE ... 59 oder eine naturräumlichen Gliederung verschiedener Größenordnungen,” (Study of the whole, in a certain landscape unit dominating complex interaction between biocoenoses and their environmental conditions. This interaction is expresses spatially in a certain spatial pattern or natural regional units at different scales“). Schmithüsen [41] extended Troll’s approach and included cultural landscapes. Neef and his scholars took the next step (towards a further development of landscape ecology in the 1950s by concentrating on two issues: basing landscape ecology on a natural science approach (for example through ‘geoecology’ and the ‘theory of geographical dimensions’), and including society and its (human) impacts on landscape ecosystems. According to Leser [23], landscape ecology deals with the interrelations of all functional and visible factors representing the landscape ecosystem. Besides, the current research agendas in Germany focus on interactions between holism and the sectoral views, principle of complementarity, relation of physical and perceptual approaches to the landscape concept, transdisciplinarity, scale-related issues. In the more applied arena, key issues are the study of environmental impacts/problems on landscapes arising from intensive farming, industrialisation and urbanisation. A key task is to use the outputs from landscape studies to help protect the most valuable landscape and nature areas, as well as to develop strategies for the sustainable management of such areas as well as for landscapes heavily impacted by human activities. Landscape diagnosis, landscape functions, and “leitbilder”. Taking human factors into account, is an essential step in the development of landscape research, esp. regarding aspects of practical application. For it, one of the most important approaches developed in Germany is the concept of landscape diagnosis. The term ‘landscape diagnosis’ was introduced in Germany in the 1950s [24] to draw the analogy with medical practice. Landscape diagnosis is based upon the results of landscape analysis, which attempts to provide a description of landscape structure in terms of its natural features, its use by people, and its dynamic characteristics. It has as its primary objective to systematically and methodically determine the ‘capability’ of landscapes to meet various social requirements and to define limiting or standard values “for securing the stability of natural conditions and for, if possible, increasing of performance capacities” [16] (Fig. 2). An important and crucial stage in diagnosis is that of landscape evaluation, which seeks to convert information about the various scientific parameters into socio-political categories as a framework for decision-making and management. This step is described by Neef [32] as the ‘transformation problem’ which is clearly complex because it involves the relations between the evaluator and the object being evaluated. At best, counting, measuring, classifying and similar procedures can be regarded as preliminary stages but not as complete evaluations; they are not enough to provide results being relevant to practical purposes (e.g., landscape planning). It is generally accepted that the goal of evaluation is objectively to identify the capacity of the landscape to perform its essential functions (i.e., to maintain its ‘natural balance’) [8, 9]. The ideas of landscape functions / potentials of nature, which had been used first by Neef [(1966) in a geographical context and later developed by Haase [15], Mannsfeld [25] and others prove as helpful approaches not only for the analysis and the assessment of the landscape but also to draft landscape-ecological targets. The term function is not only used to flag landscape or ecosystem properties such as the various fluxes of energy, mineral nutrients and or the distribution and movement of species between landscape elements, but also in their direct relation to human society. О. Bastian 60 landscape analysis determination of landscape structure and functioning physical region, ecosystem, land use (structure), landscape dynamics landscape diagnosis (landscape assessment I) determination of performances to meet socioeconomic requirements limits and normative values to secure stability of natur conditions performance capability loading and carrying capacity suitability of utilization natural potentials, resources, risks and environment degree of straining, levels of capacity, sensitivity, persistence degree of functional performance, multifunctionality, suitability availability and disposability (neighborhood effects, material and functional unwieldiness, forms of multiple utilization) landscape management landscape prognosis (landscape assessment II) assessment of possible (favorable, appropriate, necessary) landscape changes landscape planning, control, protection and architecture Figure 2: Interrelations and connections between landscape analysis, diagnosis and landscape management [18, after 17]. Landscape functions / potentials of nature characterize the capability and usability of a landscape in a broad sense. This is a suitable tool to evaluate landscapes in the context of managing such problems as soil erosion, water retention, groundwater recharge, groundwater protection, habitat function, landscape potential for recreation. On the one hand we understand by landscape functions / potentials of nature regulation and regeneration of single geofactors (and landscape compartments) and whole ecosystems (landscape complexes) as an entity, on the other hand the ability of landscape to satisfy needs and demands of human society [15, 25, 13, 28, 2, 7, 8]. Landscape assessment with the help of landscape functions and natural potentials is an important step to transform scientific knowledge to social categories, and to bridge the gap between nature (sciences) and human society. The assessment of landscape functions has to take the scale-dependence into consideration. For the particular scales / dimensions specific methods have to be applied. In view of the accelerating landscape change [e.g., 6], the knowledge of landscape functions at different times is important, esp. in the framework of qualified landscape monitoring programmes. The inclusion of assessing landscape functions / potentials of nature in studies of landscape change goes far beyond the pure comparison of structural parameters like land use or landscape elements. ASSESSMENT AND CLASSIFICATION OF LANDSCAPE ... 61 The importance of understanding the link between the ecological elements and the societal, cultural and economic aspects of landscape is also stressed by the recent discussions of the ‘leitbild’ concept in the German-language literature [14, 38]. The development of a leitbild or vision (prognosis or scenario) for a given area, is seen as providing a means whereby stakeholders can more easily choose between different alternatives for the conservation and utilization of both nature and the environment [5]. Leitbilder identify among others the essential ecological and aesthetical objectives for a given territory (reference unit) within a reasonable short timescale. They may be visualised as a picture and are an expression of an integrated view of nature conservation and landscape development. They represent a part of the rather comprehensive system of environmental targets. General environmental targets (principles, guidelines) can be further differentiated by so-called ‘objectives’ and ‘standards’ of environmental quality. The ‘objectives’ represent certain qualities of natural resources, their potentials and functions which should be maintained or developed. They are specified by standards, i.e. they are transformed into measurable indications and values [2]. The contribution to landscape visions or targets (leitbilder) deals only with special landscape-ecologically founded aspects. It is a matter of ecological norms, minimal demands, constraints, limits of threats and carrying capacity, which must be considered in order to enable a landscape-specific sustainable development. In other words, landscape targets or, in general, environmental targets can be proposed by scientists, for their implementation, however, political decisions are necessary. The development of tools and concepts that can help people develop such visions represents one of the major challenges facing contemporary transdisciplinary landscape research in Germany. Landscape classification. Beginning in early stages, landscape research dealt with the delimitation, description and classification of landscape units. For Germany, Meynen and Schmithüsen [29] should be mentioned who divided Germany into areas defind through the natural basis at la scale of 1:1 million and 1:200,000. This approach was more descriptive than basing on detailed ecological information being not available in a sufficient manner. Later, this conception was improved shifting towards a view using more analytical data, among them from field research, and stressing the bottom-up principle [e.g., 31]. In this sense, the units defined, called ‘geochores’, may be regarded as associations of mosaics of basic topic elements. The term ‘geochore’ means a geographically defined, or delineated, unit. ‘Tope’ or ‘topic’ refers to a particular locality. The most important feature of these geochores is their heterogeneous structure. The properties of choric spatial units result from the combination of topic elements, as well as their arrangement in space. Finally, on a higher level of aggregation geochores have new properties beyond the mere sum of the parts. Microgeochores (short: ‘microchores’) are combinations (mosaics) of geotopes associated on a higher level. On an average, they consist of 80 to 100 geotopes, which in most cases can be assigned to 12 to 15 different types (geoforms). The pattern of topes in microchores reflects primarily the landscape-genetic (landscape history) conditions of their development and succession. Microchores (delimited in Saxony) have an average size of 12 km² (3 to 30 km²). During the last years, for a whole German federal state (Saxony: 18,338 km², 5.1% of German territory) landscape was classified from a physical-geographical point of view by the working group ‘Natural balance and regional characteristics’ of the Saxon Academy of Sciences. The landscape units (microgeochores) were mapped, described, classified, and documented [19]. A comprehensive, rather complicated methodology was used, which combines two approaches: (1) the deductive way of working (top-down): larger areas are 62 О. Bastian subdivided step by step, and (2) the inductive way of working (bottom-up) basing on comprehensive landscape-ecological analyses. Sources of data have been: (1) soil maps (for agricultural areas – scale 1:25,000, for forestry areas – scale 1:10,000); (2) geological maps, hydrogeological maps; (3) maps of biotopes and land use. The results are: a map series 1:50,000 (55 sheets) with about 1,450 landscape units (microgeochores); documentation of each landscape unit in a written and GIS (ArcInfo) formats (characteristics according to the geocomponents: geological structure, soils, relief, waters, climate, vegetation, valuable biotopes, land use); a computer-based enquiry system as a rational base of utilization and interpretation. It is possible to assess the suitability of such (natural landscape) units for human activities, the functioning of natural balance, the carrying capacity, but also to draft regionalized targets (leitbilder) of landscape management [3, 5] Landscape planning. Within the wide range of practical applications for the results of modern landscape research, one of the most important instruments is landscape planning. Landscape planning in Germany has developed mainly out of landscape gardening and landscape architecture, but also of landscape management and nature and countryside conservation. The first landscape plans go back to the late 1930s. In its more analytic or scientific style landscape planning was developed in Germany and other countries in the 1950s. By law, the concept of landscape planning then was formally introduced as a planning instrument at federal level in Germany in 1976. Landscape planning is aimed at preservation and restoration of an effective, ecologically intact and aesthetically appealing landscape. Landscape planning is not restricted to single aspects only as the protection of flora and fauna (protection of nature in a narrow sense) and forethought for recreation, but it contains all natural resources and effects of natural balance, (i.e., soil, water, climate/air) as a natural living base for people. In other words, landscape planning deals with all landscape phenomena caused by nature or humans. Therefore, landscape planning is integrative, and it shall represent and coordinate different social values with respect to the landscape. The complex consideration of landscape (functions and uses) is important because the problems resulting from land use conflicts are not resolvable from the isolated points of view of economic branches alone. Landscape planning should take place as much as possible in a comprehensive approach, hierarchically ordered on different levels and consequently on different scales. The work in different dimensions (scales), the assessment of landscape functions / potentials of nature, the consideration of time aspects (landscape changes) are typical geographical aspects and approaches. Outlook. The role of landscape research is increasing mainly with regard to the challenges of the effective use and the protection of natural resources in the framework of the sustainable development demanding complex, transdisciplinary approaches. Landscape is the object where ecological, economic and societal spheres are integrated. Presently and in future, especially the following aspects/research questions are or will be relevant: 1. It is necessary to strengthen holistic views and to balance the relation between holism and sectoral approaches [4, 37]; 2. Two different concepts of the landscape, which developed separately over years, are still around. More and more the aesthetic and also mental aspect of the landscape is considered, when using the landscape concept. Landscape can be considered not only ASSESSMENT AND CLASSIFICATION OF LANDSCAPE ... 3. 4. 5. 6. 7. 8. 63 as a product of reality, but also of perception [e.g., 36, see also the European Landscape Convention]. According to Tress et al. [44]: “Landscape is neither a solely objective nor a purely subjective reality; it is both simultaneously. Thus, its scientific examination needs a common effort across traditional disciplines. The examination of geological, biological, aesthetic, historical, psychological, social or economic dimensions in isolation is not appropriate to landscape’s complex reality;” It is important to find a good relation between physical and mental approaches within the landscape concept; The principle of complementarity should be highlighted in research projects [4]; The problem of transformation, or evaluation, which deals with the problematic connecting of facts (natural scientific analytical knowledge of landscape and the socioeconomic demands by society) needs more and better methodological solutions; The transdisciplinary character of landscape ecology [e.g., 43] should be considered to a larger extent; Scale-related issues (i.e., methodology and dimension of validation of results) need more attention. ________________________ 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. 7. 8. 9. 10. 11. 12. 13. 14. 15. Antrop M. Geography and Landscape Science // BELGEO. 2000. No 1-4. Bastian O. The assessment of landscape functions – one precondition to define management goals // Ekológia (Bratislava). 1998a. No 17 (Suppl). Bastian O. Landscape-ecological goals as guiding principles to maintain biodiversity at different planning scales // Ekológia (Bratislava). 1998b. No 17(1). Bastian O. Landscape ecology – towards an unified discipline? // Landscape Ecology. 2002. No 16. Bastian O. Functions, leitbilder, and red lists – expression of an integrative landscape concept // Brandt J., Vejre H. (eds.) Multifunctional landscapes. Vol. I: Theory, values and history. Ashurst, Southampton: WIT Press, 2004. Bastian O., Bernhardt A. Anthropogenic landscape changes in Central Europe and the role of bioindication // Landscape Ecology. 1993. No 8. Bastian O., Röder M. Assessment of landscape change by land evaluation of past and present situation // Landscape and Urban Planning. 1998. No 41. Bastian O., Schreiber K.-F. Analyse und Bewertung der Landschaft. Jena: Gustav Fischer, 1999. Bastian O., Steinhardt U. (eds.). Development and perspectives in landscape ecology. Concepts, methods, applications. Dordrecht: Kluwer, 2002. Bork H.-R., Dalchow C., Faust B., Piorr H.-P., Schatz T. Landschaftsentwicklung in Mitteleuropa. Gotha, Stuttgart: Klett-Perthes, 1998. Buchheim W. Beiträge zur Komplementarität // Abhandl. Sächs. Akad. Wiss., Math.-nat. Kl. 1983. No 55. Burggraaff P., Kleefeld K.-D. Historische Kulturlandschaft und Kulturlandschaftselemente // Angewandte Landschaftsökologie. 1998. No 20. De Groot R.S. Functions of Nature: Evaluation of nature in environmental planning, management and decision making. Groningen: Wolters-Noordhoff, 1992. Gaede M., Potschin M. Anforderungen an den Leitbild-Begriff aus planerischer Sicht // Berichte zur Deutschen Landeskunde (Flensburg). 2001. No 75(1). Haase G. Zur Ableitung und Kennzeichnung von Naturraumpotentialen // Petermanns Geogr. Mitt. 1978. No 122(2). 64 О. Bastian 16. Haase G. Approaches to and methods of landscape diagnosis as a basis for landscape planning and landscape management // Ekológia (Bratislava). 1990. No 9(1). 17. Haase G., Barsch H., Hubrich H., Mannsfeld K., Schmidt R. (eds.). Naturraumerkundung und Landnutzung. Geochorologische Verfahren zur Analyse, Kartierung und Bewertung von Naturräumen // Beiträge zur Geographie. 1991. No 34(1). 18. Haase D., Haase G. Approaches and methods of landscape diagnosis. // Bastian O., Steinhardt U. (eds.). Development and perspectives in landscape ecology – concepts, methods and applications. Dordrecht: Kluwer, 2002. 19. Haase G., Mannsfeld K. (eds.). Naturraumeinheiten, Landschaftsfunktionen und Leitbilder am Beispiel von Sachsen // Forschungen zur deutschen Landeskunde, Vol. 250. Flensburg, 2002. 20. Haber W. Concept, origin and meaning of „landscape“. // von Droste B., Plachter H., Rössler M. (eds.). Cultural landscapes of universal value. Jena: Gustav Fischer, 1995. 21. Hard G. Die „Landschaft“ der Sprache und die „Landschaft“ der Geographen // Colloquium geograph. 1970. No 11. 22. Krönert R., Steinhardt U., Volk M. (eds.). Landscape balance and landscape assessment. Berlin, Heidelberg, New York: Springer, 2001. 23. Leser H. Landschaftsökologie. Stuttgart: Eugen Ulmer, 1997. 24. Lingner R., Carl F.E. Landschaftsdiagnose der DDR. Berlin, 1957. 25. Löffler J. Vertical landscape structure and functioning. // Bastian O., Steinhardt U. (eds.). Development and perspectives in landscape ecology – concepts, methods and applications. Dordrecht: Kluwer, 2002. 25. Mannsfeld K. Landschaftsanalyse und Ableitung von Naturraumpotentialen // Abhandl. Sächs. Akad. Wiss., Math.-nat. Kl. 1983. No 55(3). 26. Mannsfeld K. Reform der Geographieausbildung ohne theoretisches Konzept? // Die Erde. 1995. No 126. 27. Mannsfeld K., Neumeister H. (eds.). Ernst Neefs Landschaftslehre heute // Petermanns Geogr. Mitt. 1999. Suppl. Vol. 294. 28. Marks R., Müller M., Leser H.-J., Klink H.-J. Anleitung zur Bewertung des Leistungsvermögens des Landschaftshaushaltes // Forschungen zur deutschen Landeskunde, Vol. 229. Trier, 1992. 29. Meynen E., Schmithüsen J.(eds.). Handbuch der naturräumlichen Gliederung Deutschlands. Remagen: Bundesanstalt f. Landeskunde, 1953-1962. 30. Naveh Z. What is holistic landscape ecology? A conceptual introduction // Landscape and Urban Planning. 2000. No 50. 31. Neef E. Die theoretischen Grundlagen der Landschaftslehre. Gotha, Leipzig: H. Haack, 1967. 32. Neef E. Der Stoffwechsel zwischen Gesellschaft und Natur als geographisches Problem // Geographische Rundschau. 1969. No 21. 33. Neef E. Vom Fachgebiet zum Erkenntnisbereich Geographie // Petermanns Geogr. Mitt. – 1970. No 114. 34. Neef, E. Über den Begriff Komplementarität in der Geographie // Petermanns Geogr. Mitt. 1985. No 129. 35. Paffen K.H. (ed.). Das Wesen der Landschaft. Darmstadt, 1973. 36. Pedroli B. (ed.). Landscape – our home. Zeist, Stuttgart: Indigo, Freies Geistesleben, 2000. 37. Potschin M. Landscape ecology in different parts of the world. // Bastian O., Steinhardt U. (eds.). Development and perspectives in landscape ecology –concepts, methods and applications. Dordrecht: Kluwer, 2003. ASSESSMENT AND CLASSIFICATION OF LANDSCAPE ... 65 38. Potschin M., Haines-Young R. Improving the quality of environmental assessments using the concept of Natural Capital: a case study from Southern Germany // Landscape and Urban Planning. 2003. No 63. 39. Richter H. Naturräumliche Strukturmodelle // Petermanns Geogr. Mitt. 1968. No 112. 40. Schenk W. Landschaft und Kulturlandschaft – getönte Leitbegriffe für aktuelle Konzepte geographischer Forschung und räumlicher Planung // Petermanns Geogr. Mitt. 2002. No 146. 41. Schmithüsen J. Die landschaftliche Gliederung des lothringischen Raumes // Deutsches Archiv für Landes- und Volksforschung. 1942. No 6(1). 42. Schmithüsen J. Was ist eine Landschaft? // Erdkundl. Wissen. 1964. No 9. 43. Tress B., Tress G. Begriff, Theorie und System der Landschaft. Ein interdisziplinärer Ansatz zur Landschaftsforschung // Naturschutz und Landschaftsplanung. 2001. No 33(2/3). 44. Tress B., Tress G., Décamps H., d’Hauteserre A.-M. Bridging human and natural sciences in landscape research // Landscape and Urban Planning. 2001. No 57. 45. Troll C. Luftbildplan und Ökologische Bodenforschung // Z. Ges. Erdkunde. 1939. 46. Wöbse H.H. Historische Kulturlandschaften, Kulturlandschaftsteile und Kulturlandschafts-elemente // Beiträge zur regionalen Entwicklung (Hannover). 2001. No 92. 47. Zepp H., Müller M.J. (eds.). Landschaftsökologische Erfassungsstandards. Ein Methodenbuch // Forschungen zur deutschen Landeskunde, Vol. 244, Flensburg, 1999. ОЦІНКА ТА КЛАСИФІКАЦІЯ ЛАНДШАФТІВ: ВПРОВАДЖЕННЯ ТА РОЗВИТОК ЛАНДШАФТНИХ ДОСЛІДЖЕНЬ Е. НЕЕФА У САКСОНІЇ (НІМЕЧЧИНА) О. Бастіан Саксонська академія наук, Дрезден, Д-01097 Німеччина Olaf.Bastian@mailbox.tu-dresden.de Наукова концепція ландшафтних досліджень, сформульована німецьким географом Е. Неефом, стала основою для аналізу, діагнозу та прогнозу людського середовища. Вона дуже важлива для сучасного ландшафтного планування. Короткий історичний огляд демонструє різні парадигми щодо визначення та дослідження ландшафту. Дрезденська робоча група “Природний баланс та регіональні характеристики” Саксонської академії наук опрацювала такі питання, як класифікація ландшафтів “знизу догори”, потенціал природних та ландшафтних функцій, ландшафтні сценарії (leitbilder). Щодо прикладних досліджень ландшафту, то усе більшої ваги набувають комплексні, комплементарні та трансдисциплінарні підходи. Ключові слова: ландшафт, ландшафтна екологія, географія, просторові одиниці, ландшафтне планування. Стаття надійшла до редколегії 12.04.2004 Прийнята до друку 16.06.2004