The Approach to Childhood Interstitial Lung Disease

advertisement

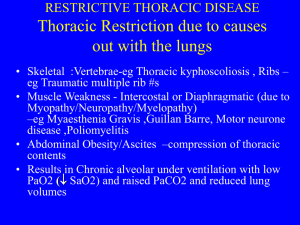

The approach to childhood interstitial lung disease Ernst Eber, MD Correspondence Prof. Dr. Ernst Eber Respiratory and Allergic Disease Division Paediatric Department Medical University of Graz Auenbruggerplatz 30 A-8036 Graz, AUSTRIA Tel.: +43 316 385 12620 Fax: +43 316 385 14621 ernst.eber@medunigraz.at 1 Summary Presentation of childhood interstitial lung disease (ILD) is usually nonspecific, and a systematic approach to diagnosis is essential. In most cases, confirmation of the presence of ILD is obtained by a high-resolution computed tomography, and the assessment of severity by lung function testing (inluding blood gas analysis). Lung biopsy usually represents the final step in a series of diagnostic methods. Childhood ILD is difficult to diagnose, but precise diagnosis is crucial because of genetic and therapeutic implications. There are no randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled therapeutic trials in childhood ILD. A few children do not require any treatment or only oxygen therapy, and recover spontaneously. Most children will need corticosteroid therapy which may be combined with hydroxychloroquine. For the future, there is an urgent need for international collaboration which will allow to collect sufficiently large cohorts of patients with specific entities in order to perform proper therapeutic trials. As a prerequisite, a clear and standardised classification of the histopathology of the underlying conditions has to be developed. Such multicentre trials will help to reduce the still considerable morbidity and mortality in children with ILD. Key words Bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL), imaging, lung biopsy, lung function testing, monitoring, treatment Presentation of childhood interstitial lung disease and approach to diagnosis Childhood interstitial lung disease (ILD) represents a heterogeneous group of respiratory disorders that are mostly chronic and associated with high morbidity and mortality. The frequency of ILD is much lower in children than in adults, but in children ILD comprises a broader spectrum of disorders. This is linked to the fact that the disease occurs in the context of lung growth at the various stages of alveolar development and maturation. ILD frequently occurs in young children (often with neonatal onset of symptoms), the prevalence of chronic ILD is higher in boys than in girls, and a substantial proportion of patients have a family history of lung disease. Presentation of ILD in infants and children is usually nonspecific. Presenting features are hypoxaemia, tachypnoea, subcostal retractions and other signs of respiratory distress, failure to thrive, crackles, cough and also wheeze. History and physical examination A systematic approach to diagnosis is essential, and should start with an accurate clinical history and physical examination. The presence and onset of respiratory signs and symptoms should be noted, and the presence of ILD in other family members should be sought as well as any relationship to feeding, possible inhalant triggers in the environment, and features suggestive of a multi-system disease. Physical examination may reveal signs of respiratory distress, such as tachypnoea and 2 subcostal retractions, and crackles. Rarer findings associated with an advanced stage of the disease include digital clubbing and cyanosis during exercise or at rest. Laboratory tests While laboratory tests are rarely diagnostic, in most cases a panel of tests will be performed in an attempt to determine the cause of ILD. A selective approach is recommended, with the spectrum of investigations being guided by the history and clinical presentation of the child. As an example, precipitating immunoglobulin G antibodies against airborne allergens would suggest hypersensitivity pneumonitis if there is a compatible history. In most children with ILD, searching for mutations in the surfactant protein (Sp)-B, Sp-C, and ABCA3 genes will be indicated. Further, laboratory tests may be helpful to exclude systemic disorders (such as immunodeficiencies or collagen vascular diseases that can be associated with interstitial lung involvement), and more common respiratory diseases in childhood that do not typically present with diffuse pulmonary disease (such as cystic fibrosis or tuberculosis). Imaging The chest radiograph may show ground-glass, nodular, reticular, or reticulonodular shadowing, and honeycombing in advanced disease. However, in some children with ILD the chest radiograph may be normal. In general, chest radiographs have poor sensitivity and poor specificity, and correlate poorly with symptoms, histology, and response to treatment. Consequently, the key chest imaging tool for both diagnosis and management of a child with ILD is high-resolution computed tomography (HRCT). In most cases, confirmation of the presence of ILD is obtained by an HRCT scan. HRCT may allow specific diagnoses (e.g. Langerhans cell histiocytosis, hypersensitivity pneumonitis) to be established only in very few cases. With the most common HRCT feature being widespread ground-glass attenuation, HRCT is not a diagnostic investigation for most children with ILD. In addition, HRCT may be used to determine the site of a lung biopsy, and it may also contribute to monitor disease activity and/or severity. Lung function testing Lung function testing does not provide specific information, but represents a useful tool for assessing severity and monitoring therapy. Generally, in older children lung function abnormalities reflect a restrictive ventilatory defect with decreased lung volumes, reduced forced expiratory volume in 1 s (FEV1) and forced vital capacity (FVC), with a normal or increased FEV1/FVC ratio. Lung function testing in infants and pre-school children is still considered a research technique. The majority of patients show hypoxaemia; hypercarbia occurs only late in the disease course. Pulse oximetry and blood gas analysis (arterial or arterialised blood) should be performed at room air at rest in every child with (suspected) ILD. In addition, oxygen saturation (SaO2) and/or blood gases may also be determined during exercise (e.g. cycle ergometer, treadmill). Bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) Flexible bronchoscopy and BAL are diagnostic in only a few specific conditions (such as Langerhans cell histiocytosis, pulmonary alveolar proteinosis and lipoid pneumonia), and may be useful in several diseases (such as sarcoidosis and hypersensitivity pneumonitis). BAL is very good for the diagnosis of opportunistic 3 infections in immunocompromised children, in particular if there was no prior antibiotic or antifungal therapy. Usually, BAL is carried out in the most affected area (identified radiologically). In diffuse ILD, BAL is mostly performed in the middle lobe, or, for infants, in the lower lobe. Lung biopsy Histological evaluation of lung tissue usually represents the final step in a series of diagnostic methods. It is recommended to perform a lung biopsy ahead of blind trials of treatment unless the child is too sick, or a specific diagnosis has been made by other techniques. Available techniques include transbronchial biopsy, percutaneous CT-guided needle lung biopsy, video-assisted thoracic surgery (VATS) and lung biopsy via a mini-thoracotomy. Samples from transbronchial biopsies are usually small and thus not adequate for the pathologist to make a diagnosis; for both transbronchial and percutaneous biopsies there is a considerable risk of bleeding and pneumothorax. Thus, a surgical biopsy is the method of choice, with a number of centres now confirming VATS to be a safe procedure even in small children. ILD is frequently patchy and it is, therefore, essential that representative areas are sampled. HRCT scanning provides a reliable guide in this respect, directing the surgeon to areas with active disease and avoiding those where the process is burnt-out. Close collaboration between surgeon and pathology laboratory is essential. Treatment There are no randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trials in childhood ILD. Thus, current treatment regimens for children are based on anecdote and/or are derived from information provided by studies in adult patients, although expression and outcome of ILD in children differ from adult ILD. General measures Supportive care includes administration of oxygen for chronic hypoxaemia, adequate nutrition, annual immunisation with influenza vaccine along with other routine immunisations against respiratory pathogens, aggressive treatment of intercurrent infections, strict avoidance of tobacco smoke and other air pollutants, and the selective use of bronchodilators. Further, the treatment of associated gastrooesophageal reflux, whether it is a primary or secondary phenomenon, may be important. Pharmacologic therapy A few children with very mild disease do not require any treatment and recover spontaneously. In the majority, however, treatment with immunosuppressive, antiinflammatory, or anti-fibrotic drugs is required for months to years. Although responses to steroids are highly variable, a trial of corticosteroids for at least six to eight weeks should be considered in every child with idiopathic ILD. The most commonly used treatment consists of oral prednisolone in a start dose of 2 mg/kg/day. Alternatively, intravenous methylprednisolone may be given at a dose of 10-30 mg/kg (or 500 mg/m2) for three consecutive days at monthly intervals, usually for six months. As pulsed steroid therapy may be associated with fewer side effects, today this therapeutic strategy is preferred by a number of authors. Morbidity and 4 mortality associated with ILD has to be balanced against the treatment risks; thus, any medication has to be titrated to the lowest dose resulting in clinical stability. There are no evidence-based criteria available that may be used for discontinuation of corticosteroid treatment. A number of alternative or steroid-sparing agents has been used with anecdotal success in children with ILD; of these, the anti-malarial drug hydroxychloroquine (610 mg/kg/day in two doses) is the preferred agent. However, similar to steroids, responses to hydroxychloroquine are highly variable. Patients with severe disease may benefit from a combination of corticosteroids and hydroxychloroquine. When steroids and hydroxychloroquine are not successful, or when there is evidence of severe steroid side effects, other immunosuppressive or cytotoxic agents such as azathioprine, cyclophosphamide, cyclosporin, or methotrexate may be used, but evidence is even more anecdotal. Specific treatment strategies Patients with underlying systemic disorders require primary treatment for these disorders, e.g. chemotherapy for malignancy, or intravenous gamma globulin for hypogammaglobulinaemia. Specific therapeutic strategies include anti-infective therapy for chronic respiratory infections (e.g. cytomegalovirus or Epstein-Barr virus infection), interferon- for pulmonary haemangiomatosis, pulsed cyclophosphamide for Wegener’s granulomatosis, and whole lung lavage and inhaled or subcutaneous GM-CSF in idiopathic pulmonary alveolar proteinosis. In patients with hypersensitivity pneumonitis, avoidance of the causative environmental antigen is of fundamental importance. Furthermore, in patients treated with corticosteroids or cytotoxic agents chronically, prophylaxis against Pneumocystis jirovecii with trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole should be considered. Transplantation Lung or heart-lung transplantation may be offered as ultimate therapy for end-stage ILD and for some lethal diseases such as those caused by mutations in the Sp-B and ABCA3 genes. In recent years, transplantation has been shown to be a viable option in children of all ages, even in young infants. There have been a few reports on the recurrence of ILD in the recipient lung (e.g. Langerhans cell histiocytosis, sarcoidosis). Novel therapeutic approaches New approaches to treatment of ILD involve substances directed against the action of cytokines, growth factors and oxidants. Several of these agents (e.g. interferon-γ, pirfenidone) have shown promise at the clinical trial stage in adult patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Another cytokine-based approach is inhibition of tumour necrosis factor (TNF)- in patients with pulmonary sarcoidosis; infliximab, pentoxifylline, etanercept, and thalidomide have been studied in adult patients. Monitoring There are no well established guidelines to monitor the course of illness in children with ILD. Usually, patients are assessed at regular intervals of three to six months or 5 more frequently if severely ill. While in older children the response to treatment can be assessed by lung function testing, in infants and small children decrease in tachypnoea, return of weight gain and growth to normal levels, improved exercise tolerance, and an increase in resting oxygen saturation levels of 3-4% are considered to indicate a favourable response. As improvements on HRCT scans tend to occur only over longer periods of time and radiation exposure should be minimised, imaging plays a limited role. Repeat BAL appears to be indicated in pulmonary haemorrhagic syndromes only. References Bush A, Nicholson AG. Paediatric interstitial lung disease. Eur Respir Mon 2009; 46: 319-354. Clement A, Allen J, Corrin B, Dinwiddie R, Ducou le Pointe H, Eber E, Laurent G, Marshall R, Midulla F, Nicholson AG, Pohunek P, Ratjen F, Spiteri M, de Blic J. Task force on chronic interstitial lung disease in immunocompetent children. Eur Respir J 2004; 24: 686-697. Clement A, Eber E. Interstitial lung diseases in infants and children. Eur Respir J 2008; 31: 658-666. Deutsch GH, Young LR, Deterding RR, Fan LL, Dell SD, Bean JA, Brody AS, Nogee LM, Trapnell BC, Langston C; Pathology Cooperative Group, Albright EA, Askin FB, Baker P, Chou PM, Cool CM, Coventry SC, Cutz E, Davis MM, Dishop MK, Galambos C, Patterson K, Travis WD, Wert SE, White FV; ChILD Research Cooperative. Diffuse lung disease in young children: application f a novel classification scheme. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2007; 176: 1120-1128. Fan LL, Deterding RR, Langston C. Pediatric interstitial lung disease revisited. Pediatr Pulmonol 2004; 38: 369-378. 6