The sociolinguistics of borrowing: Georgian moxdoma and Russian

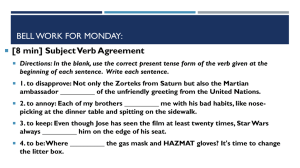

advertisement

In: Rudolf Muhr (ed.) (2006): Reproduction and Innovation in Language and Communication in different Language Cultures / Reproduktionen und Innovationen in Sprache und Kommunikation verschiedener Sprachkulturen. Wien u.a., Peter Lang Verlag. S. Nino AMIRIDZE and Olga GUREVICH (Utrecht University and UC Berkeley) Nino.Amiridze@let.uu.nl and olya.gurevich@gmail.com The sociolinguistics of borrowing: Georgian moxdoma and Russian proizojti ‘happen’ 1 Abstract Georgian is usually described as a highly synthetic language. In this paper, we examine an analytical construction which emerged in the last few decades, possibly under the influence of a similar Russian construction. We examine the structural similarities between the two constructions and focus on their discourse / pragmatic functions. We argue that the Georgian construction is used to make the speaker sound authoritative and official, while the Russian construction serves mostly to de-emphasize the role of the agent in an event. We explore the development of the Georgian construction and possible cultural routes by which it acquired its sociolinguistic load. 1. Introduction The distinction between synthetic and analytical languages is a very basic one in modern linguistics. However, most languages do not fall neatly into just one or the other category. This paper illustrates an example of fluidity between synthetic and analytical constructions within a single language, Georgian (Kartvelian). We describe the emergence of an analytical construction involving a light verb and a deverbal noun that exists in parallel with, and sometimes replaces, a synthetic construction with an inflected verb. We suggest that the development of this construction is a natural process, supported by similar cross-linguistic and historical developments. We further explore the social and pragmatic uses of this construction, which provides a unique glance at grammaticalization in progress. Georgian is known as a highly flectional, possibly even agglutinative 1 We would like to thank Alice C. Harris, Johanna Nichols, Kevin Tuite, and the audience at the CESS 2005 conference in Boston for helpful comments and discussion. All errors remain our responsibility. This research was in part supported by the Language in Use project of the Utrecht Institute of Linguistics OTS. In: Rudolf Muhr (ed.) (2006): Reproduction and Innovation in Language and Communication in different Language Cultures / Reproduktionen und Innovationen in Sprache und Kommunikation verschiedener Sprachkulturen. Wien u.a., Peter Lang Verlag. S. language. Georgian verbs inflect for a variety of categories (such as tense, mood, aspect, causality, and voice) and a single verb can often mean as much as a whole sentence in a standard European language. However, an alternative way of constructing complex predicates has emerged in the last few decades. The new construction involves the verbs moxdoma ‘to happen’ or moxdena ‘to make happen’ used in conjunction with a deverbal noun to indicate an event (1a). The new analytical construction is sometimes interchangeable with a more traditional synthetic construction (1b), and in other cases is the only way to express a complex event. 1. a. @samartaldamcav-eb-i -a-xd-en-en današaul-ta mičkmalva-s.2 law.enforcement.official-PL-NOM3 3BDAT.SG-PRV-happen-CAUS-3ANOM.PL crime-PL.GEN hiding.away-DAT Lit.: The law enforcement officials make-happen the hiding of crimes. ‘The law enforcement officials hide crimes.’ b. samartaldamcav-eb-i -čkmal-av-en današaul-eb-s. law.enforcement.official-PL-NOM 3BDAT.SG-hide.away-TS-3ANOM.PL crime-PLDAT ‘The law enforcement officials hide crimes.’ In the body of the paper, we explore the usage and development of this construction. We suggest that it started out with lexical verbs (section 3), then developed under the influence of Russian verbs proizojti ‘happen’ / proizvesti ‘make happen’ being used as light verbs (section 2). It appears that the Russian usage served as an initial catalyst, but the analytical construction has developed in its own right in Georgian. We examine the special morphosyntactic properties of the construction (section 4), and focus on the discourse / pragmatic functions of the analytical construction. We suggest that the main purpose of the construction is to make the speaker sound official and authoritative (section 5), but that the analytical construction also provides a lexical disambiguation mechanism in some instances 2 The ‘@’ sign indicates that the sentence was attested in natural discourse. Most of our data comes from the Internet. 3 Abbreviations: 1=1st person; 2=2nd person; 3=3rd person; A=Set A agreement marker; ACC=accusative; ADV=adverbial; AOR=aorist; B=Set B agreement marker; CAUS=causative; COP=copula; DAT=dative; DIST=distal demonstrative; ERG=ergative; FEM=feminine; GEN=genitive; IMPERF=imperfect; INST=instrumental; INTR=intransitive; MASC=masculine; NEG=negative; NEUT=neuter; NOM=nominative; PART=particle; PAST=past tense; PL=plural; PRV=pre-radical vowel; PV=preverb; SG=singular; SUBJ=subjanctive; TS=thematic suffix. The indices show the case of the argument triggering the particular agreement marker. For instance, 1AERG.SG=1st person singular Set A agreement marker triggered by the ERG argument; 2BDAT.SG=2nd person singular Set B agreement marker triggered by the DAT argument; 3ANOM.PL=3rd person plural Set A agreement marker triggered by the NOM argument. In: Rudolf Muhr (ed.) (2006): Reproduction and Innovation in Language and Communication in different Language Cultures / Reproduktionen und Innovationen in Sprache und Kommunikation verschiedener Sprachkulturen. Wien u.a., Peter Lang Verlag. S. (section 6). We conclude by emphasizing the importance of real-life data work (most of our data comes from examining media reports, TV transcripts, and other texts available on the Internet) (section 7). We suggest that a grammaticalization change is taking place in Georgian that is worth further study and could provide important insights into the distinction between synthetic and analytical structures, as well as information about the sociolinguistic situation in modern Georgian. 2. Possible Source: Russian proizojti and proizvesti We would like to suggest that the Georgian moxdoma / moxdena construction originated at least in part under the influence of Russian. In contemporary Russian, the verbs proizojti ‘happen’ and proizvesti ‘make happen, create’ are often used as light verbs together with deverbal nouns instead of corresponding lexical verbs. This is particularly common in media reports and official speeches. The intransitive version of the construction involves the verb proizojti and a noun or deverbal nominal as its theme (2a vs. 2b). 2. a. @V londonskom metro proizoshel vzryv. in London metro happen.PAST.3SG.MASC explosion ‘An explosion occurred in the London metro.’ b. V londonskom metro terrorist vzorval bombu. in London metro terrorist.NOM explode.PAST bomb.ACC ‘A terrorist exploded a bomb in the London metro.’ A patient argument can sometimes be expressed in a possessive phrase: 3. @Ne schitayu, chto u menya proizoshla ssora s bratom. not consider.1SG that at me.GEN happen.PAST fight with brother Lit: I do not consider that at me a fight with brother happened. ‘I do not think that I had a fight with my brother.’ The main discourse-pragmatic function of the construction with proizojti appears to be the anonymization or distancing of the agent, which is not mentioned. The defocusing of the agent here is more extreme than in a passive construction, where the agent could still be expressed in an oblique phrase (4). 4. V londonskom metro terroristom byla vzorvana bomba. in London metro terrorist.INST was exploded.PART bomb.NOM In: Rudolf Muhr (ed.) (2006): Reproduction and Innovation in Language and Communication in different Language Cultures / Reproduktionen und Innovationen in Sprache und Kommunikation verschiedener Sprachkulturen. Wien u.a., Peter Lang Verlag. S. ‘A bomb was exploded in the London metro by a terrorist.’ In the vast majority of attested examples, the noun indicating the event comes after the verb proizojti. The post-verbal position is typically focused in Russian, consistent with the fact that this construction serves to defocus the agent and put more focus on the event. The transitive construction with proizvesti ‘make happen’ keeps the overt agent, but adds a sense of indirectness (indirect causality) to the action. In (5b), the agent is seen as taking direct physical action to change the leadership; by contrast, in (5a), the agent is still responsible for the change, but possibly in some indirect manner. 5. a. @Berezovskij proizvel smenu rukovodstva v ‘Kommersante’. Berezovskij made.happen change leadership in ‘Kommersant’ ‘Berezovskij induced a change of leadership in ‘Kommersant’.’ b. Berezovskij smenil rukovodstvo v ‘Kommersante’. Berezovskij changed leadership in ‘Kommersant’ ‘Berezovskij changed the leadership in ‘Kommersant’[newspaper].’ The proizojti / proizvesti construction often occurs in official speeches and news coverage. It most likely originated during the Soviet times as part of socalled ‘block writing’ (Seriot 1986), which included extensive use of nominalizations to present certain ideological concepts as background information and therefore difficult to debate or question. The light verbs proizojti and proizvesti are most often used with deverbals denoting momentous, sudden events, often of catastrophic nature. Table 1 demonstrates some of the most frequently used deverbals (based on a Google search). The verb proizojti is originally a motion verb, meaning literally ‘to come out of (perfective).’ It can be used as a lexical verb meaning ‘originate’, ‘evolve’; proizvesti is a causative / transitive version of the same. Cross-linguistically, light verbs and auxiliaries often come from motion verbs, and so this use of proizojti is not unexpected. In modern Georgian, a construction structurally similar to the Russian proizojti-construction has emerged in the last few decades. The verb moxdoma ‘happen’ is used as a light verb in conjunction with a deverbal noun where previously a lexical verb would have been preferred. The rest of this paper examines this new construction in detail. First, however, we look at uses of In: Rudolf Muhr (ed.) (2006): Reproduction and Innovation in Language and Communication in different Language Cultures / Reproduktionen und Innovationen in Sprache und Kommunikation verschiedener Sprachkulturen. Wien u.a., Peter Lang Verlag. S. moxdoma / moxdena as a lexical verb. proizoshel (PAST.MASC.SG) vzryv pozhar vybros sboj incident terakt boj vzlom sliv ‘explosion’ ‘fire’ ‘dump’ ‘break’ ‘incident’ ‘terror act’ ‘battle’ ‘break-in’ ‘leak’ proizoshla (PAST.FEM.SG) avariya smena oshibka utechka tragediya draka stychka perestrelka katastrofa ‘accident’ ‘change’ ‘error’ ‘leak’ ‘tragedy’ ‘fight’ ‘fight’ ‘shoot-out’ ‘catastrophe proizoshlo (PAST.NEUT.SG) zemletryasenie stolknovenie otklyuchenie sobytie vozgoranie snizhenie ubijstvo uvelichenie DTP ‘earthquake ‘collision’ ‘shut-down’ ‘event’ ‘fire’ ‘lowering’ ‘murder’ ‘increase’ ‘road accident’ proizvesti (Transitive) vzryv vyemku posadku vyplatu zapusk arest remont perevorot naznacheniya ‘explosion’ ‘extraction’ ‘landing’ ‘payment’ ‘launch’ ‘arrest’ ‘repairs’ ‘coup’ ‘appointments’ Table 1. Some common deverbal nouns with proizojti and proizvesti. 3. Moxdoma / moxdena ‘(make) happen’ as a Lexical Verb As a lexical verb the inflected unaccusative root -xd- ‘happen’ is used in all the three Tense-Aspect-Mood (TAM) Series (see Table 2). It is associated with only one argument, a Theme (6a). However, the addition of an extra possessor argument is also possible (6b vs. 7). The lexical semantics of the verb specify that the Theme argument must refer to an event. As such, it is always 3rd person inanimate (6a). Since inanimate arguments do not trigger plural agreement in Georgian, the forms of moxdoma are always in the singular. 6. a. avaria mo-xd-a. car.accident.NOM PV-happen-3ANOM.SG.AOR Lit.: Car.accident it.happened ‘There happened a car accident.’ b. avari-eb-i mo-xd-a / *mo-xd-nen. car.accident-PL-NOM PV-happen-3ANOM.SG.AOR PV-happen- 3ANOM.PL.AOR ‘There happened car accidents.’ 7. (me) avaria mo-m-i-xd-a. I.DAT car.accident.NOM PV-1BDAT.SG-PRV-happen-3ANOM.SG.AOR Lit: To.me car.accident it.happened.to.me ‘I had a car accident.’ Series Sub-Series Screeves Present Indicative I Present Imperfect Indicative Intransitive -xdxdeba ‘it happens.’ xdeboda ‘It was happening.’ In: Rudolf Muhr (ed.) (2006): Reproduction and Innovation in Language and Communication in different Language Cultures / Reproduktionen und Innovationen in Sprache und Kommunikation verschiedener Sprachkulturen. Wien u.a., Peter Lang Verlag. S. Series Sub-Series Screeves Present Subjunctive Future Indicative Future Conditional Future Subjunctive Aorist Indicative II Aorist Subjunctive Perfect III Pluperfect 3rd Subjunctive Intransitive -xdxdebodes ‘[If] it were happening.’ moxdeba ‘It will happen.’ moxdeboda ‘It would happen.’ moxdebodes ‘[If] it would happen.’ moxda ‘It happened’ moxdes ‘[In order for] it to happen.’ momxdara ‘It has happened.’ momxdariq’o ‘[If] it had happened.’ momxdariq’os ‘[As if] it had happened.’ Table 2. Intransitive -xd- in TAM Series in Georgian. If the root occurs with a causative suffix (-in or -en, depending on TAM series), we get a transitive stem -xd-in/-en ‘make happen’ (8): 8. mat revolucia mo--a-xd-in-es. they.ERG revolution.NOM PV-3BNOM.SG-PRV-happen-CAUS-3AERG.PL.AOR Lit: they revolution they.made.it.happen ‘They made a revolution.’ Both the inflected intransitive -xd- (see 6a, 9a, 10a) and the transitive -xdin/-en (8) occur in combination with nominals referring to unexpected and catastrophic events. 9. a. sapranget-is revolucia mo-xd-a 1789 c’el-s. France-GEN revolution.NOM PV-happen-3ANOM.SG.AOR 1789 year-DAT Lit.: French revolution it.happened 1789 year.in ‘The French revolution was carried out in 1789.’ b. *sapranget-ši ga-revoluci-av-d-a 1789 c’el-s. France-in PV-revolution-TS-INTR-3ANOM.SG.AOR 1789 year-DAT ‘The French revolution was carried out in 1789.’ Often, this is the only way to make a predicate out of a noun with no corresponding synthetic verb (cf. 10a vs. 10b as well as Table 3). 10. a. mo-xd-a sasc’aul-i: zamtar-ši xe gaq’vavda. PV-happen-3ANOM.SG.AOR miracle-NOM winter-in tree.NOM Lit.: It.happened miracle: winter.in tree it.blossomed ‘A miracle was performed: A tree blossomed in winter.’ b. *ga-sasc’aul-d-a. PV-miracle-INTR-3ANOM.SG.AOR ‘A miracle was performed.’ it.blossomed In: Rudolf Muhr (ed.) (2006): Reproduction and Innovation in Language and Communication in different Language Cultures / Reproduktionen und Innovationen in Sprache und Kommunikation verschiedener Sprachkulturen. Wien u.a., Peter Lang Verlag. S. Native Georgian Nominal Stems sasc’aulgadat.rialebaštabeč’dilebatvit+gamoxat’va(ze)+gavlenaze+c’ola- ‘miracle’ ‘coup’, ‘upheaval’ ‘impression’ ‘self-expression’ ‘influence’ ‘oppression’ Possible Synthetic Verb Form *v-a-sasc’aul-eb *gada-v-a-t’rial-eb *v-a-štabeč’dil-eb *tvit-gamo-v-xat’-av *(ze)-ga-v-a-vlen *ze-v-c’ol-av ‘I make a miracle.’ ‘I stage a coup / an upheaval.’ ‘I make an impression.’ ‘I express myself’ ‘I influence him/her/it.’ ‘I oppress him/her.’ Table 3. Some Native Georgian Nouns Used in the Construction with the Inflected Intransitive -xd- and Transitive -xd-in/-en. However, this is not the only group of nouns that can act as a Theme argument of the inflected intransitive -xd- ‘happen’ or the transitive -xd-in/-en ‘make happen’. Many borrowed nouns with no corresponding synthetic verb forms are turned into complex predicates via the use of -xd- and -xd-in/-en (cf. 6a vs. 11, 9a vs. 9b, 12a vs. 12b as well as Table 4):4 11. *ga-avaria-v-d-a. PV-car.accident-TS-INTR-3ANOM.SG.AOR Lit: it.car.accident-ed ‘There happened a car accident.’ 12. a. @danarčen-is rek’onst’rukcia-s mexsiereba -a-xd-en-s. (Siamashvili 2001) rest-GEN reconstruction-DAT memory.NOM 3BDAT.SG-PRV-happen-CAUS3ANOM.SG Lit: of.rest reconstruction memory it.makes.it.happen ‘The reconstruction of the rest happens from memory .’ b. *danarčen-s mexsiereba -a-rek’onst’ruir-eb-s. rest-DAT memory.NOM 3BDAT.SG-PRV-reconstruct-TS-3ANOM.SG Lit: rest memory it.makes.it.reconstruct ‘ One reconstructs the rest from memory.’ Borrowed Nominal Stems p’araliz-eb-ašok’+ir-eb-at.ransl+ir-eb-ap’roduc+ir-eb-ablok’+ir-eb-ak’orek+ciaepekt’- 4 ‘paralyzing’ ‘shocking’ ‘transmission’ ‘production’ ‘blocking’ ‘correction’ ‘effect’ Possible Synthetic Verb Form *v-a-p’araliz-eb *v-a-šok’ +ir-eb / v-šok’-av *v-a-t’ransl+ir-eb *v-a-p’roduc+ir-eb *v-a-blok’ +ir-eb / v-blok’-av *v-a-k’orekci-eb *v-a-epekt’-eb ‘I paralyze him/her/it.’ ‘I shock him/her.’ ‘I broadcast it.’ ‘I produce it.’ ‘I block him/her/it.’ ‘I correct it.’ ‘I affect him/her/it.’ Note that in Table 4 there are two synthetic verb forms v-šok’-av ‘I shock him/her’ and v-blok’-av ‘I block him/her/it,’ but these are derived directly from the borrowed nominals such as šok’- ‘shock’ and blok’‘block’ rather than from the nominals such as šok’+ir-eb-a- ‘shocking’ and blok’+ir-eb-a- ‘blocking’. In: Rudolf Muhr (ed.) (2006): Reproduction and Innovation in Language and Communication in different Language Cultures / Reproduktionen und Innovationen in Sprache und Kommunikation verschiedener Sprachkulturen. Wien u.a., Peter Lang Verlag. S. Table 4. Some Borrowed Nominal Stems Used in Light Verb Constructions. Probably by analogy with the above lexical uses, there are now new analytical constructions with the intransitive root -xd- and its transitive counterpart -xd-in/-en even when there is a synthetic verb form available (1, repeated as 13). The synthetic verb form (-čkmal-av-en in 13b) is made into a deverbal nominal, known to Kartvelianists as a masdar (mičkmalva-s in 13a) and marked as a theme argument of the inflected -xd- or -xd-in/-en. 13. a. @samartaldamcav-eb-i -a-xd-en-en današaul-ta mičkmalva-s. law.enforcement.official-PL-NOM 3BDAT.SG-PRV-happen-CAUS- 3ANOM.PL crime-PL.GEN hiding.away-DAT Lit.: The law enforcement officials make-happen the hiding of crimes. ‘The law enforcement officials hide crimes.’ b. samartaldamcav-eb-i -čkmal-av-en današaul-eb-s. law.enforcement.official-PL-NOM 3BDAT.SG-hide.away-TS-3ANOM.PL crime-PLDAT ‘The law enforcement officials hide crimes.’ The deverbal nominal mičkmalva-s ‘hiding away’ is associated with a certain argument structure, and the form -a-xd-en-en does not seem to be used as a lexical verb (13a). The lexical semantics is provided by the masdar nominal while the TAM as well as agreement marking are provided by the grammatical form -a-xd-en-en. The pragmatics or why and when people prefer to use an analytical construction instead of a corresponding synthetic verb form will be discussed in section 5. But first we explore the morphosyntactic status of the inflected -xd- and -xd-in/-en taking masdar nominals as Theme. 4. On the Morphosyntax of Georgian Light Verb Constructions Let us look at another example employing an inflected transitive light verb xd-en/-in ‘make it happen’. Although there is a synthetic verb form gan--azogad-eb-s ‘(s)he generalizes it’ (14b), Modern Georgian also offers an analytical construction -a-xd-en-s ganzogadeba-s with the inflected transitive stem -a-xden-s ‘(s)he makes it happen’ and a dative-marked masdar form ganzogadeba-s ‘generalizing/generalization’ (14a): 14. a. @is mecnier-i k’i, romelic k’rit’ik’-is ist’oria-s c’ers, -a-xd-en-s In: Rudolf Muhr (ed.) (2006): Reproduction and Innovation in Language and Communication in different Language Cultures / Reproduktionen und Innovationen in Sprache und Kommunikation verschiedener Sprachkulturen. Wien u.a., Peter Lang Verlag. S. zemotkmul-is ganzogadeba-s... (Tchanturaia 2001) DIST.NOM scientist-NOM PART which/who.NOM criticism-GEN historyDAT (s)he.writes.it 3BDAT.SG-PRV-happen-CAUS-3ANOM.SG above.said-GEN generalizing-DAT ‘As for the scholar, who writes the history of criticism, (s)he generalizes the above said...’ b. (is) gan--a-zogad-eb-s zemotkmul-s. (s)he.NOM PV-3BDAT.SG-PRV-general-TS-3ANOM.SG above.said-DAT ‘(S)he generalizes the above said.’ The NP argument of the intransitive or transitive light verb consists of the head (the masdar form of the corresponding synthetic form) and a genitive-marked determiner, which corresponds to the theme argument of the corresponding synthetic form. For instance, the head noun ganzogadeba-s of the dative NP zemotkmul-is ganzogadeba-s that serves as the theme argument of the light verb -a-xd-en-s (14b) is the masdar form of the synthetic verb form gan--a-zogadeb-s. And the determiner zemotkmul-is corresponds to the theme argument of the corresponding synthetic form gan--a-zogad-eb-s in (14a). Grammatical information in the synthetic forms is preserved in the corresponding analytical construction. The syntactic status of the theme argument of the synthetic form changes in analytical constructions in the sense that it becomes a determiner of an NP. However, the lexical and thematic structure of the predicate remains intact. The constructions using the intransitive light verb serve a function similar to the one in Russian (de-focusing the agent), although it seems that the agent can more often be expressed in an oblique phrase. More precisely, there are several options. The agent may not be present at all (20a); may be expressed in a postpositional phrase headed by mier ‘by’ (15a); or in a postpositional phrase headed by -gan ‘from,’ which requires its noun to be in the genitive (16): 15. a. @mis mier mo-xd-a mekanik’ur-i šecdom-is dašveba. (Toklikishvili 2005) (s)he.GEN by PV-happen-3ANOM.SG.AOR mechanical-NOM mistake-GEN making/committing.NOM ‘There was a mechanical error committed/made by him/her.’ b. man da--u-šv-a mekanik’ur-i šecdoma. (s)he.ERG PV-3BNOM.SG-PRV-commit/make-3AERG.SG.AOR mechanical-NOM mistake.NOM ‘(S)he made/committed a mechanical error.’ In: Rudolf Muhr (ed.) (2006): Reproduction and Innovation in Language and Communication in different Language Cultures / Reproduktionen und Innovationen in Sprache und Kommunikation verschiedener Sprachkulturen. Wien u.a., Peter Lang Verlag. S. 16. @gaačnia, vis-gan mo-xd-eb-a čareva. it.depends who.GEN-from PV-happen-TS-3ANOM.SG intervening.NOM ‘It depends from whom an intervention will be made .’ (=It depends who will intervene). The transitive light verb -xd-en/-in, on the other hand, does not serve to defocus the agent. On the contrary, the agent is always there. For instance, in 17 the agent is presented as an NP čven-i c’inap’r-eb-i; it is the grammatical subject, as indicated by the nominative case marking and the corresponding Set A agreement suffix –nen on the verb. Neither a mier phrase (18a) nor a PP (18b) is grammatical: 17. @čven-i c’inap’r-eb-i -a-xd-en-d-nen ... bunebriv-i kv-eb-is damušaveba-s. (mer 2000) our-NOM ancestor-PL-NOM 3BDAT.SG-PV-happen-CAUS-IMPERF-3ANOM.PL ... natural-NOM stone-PL-GEN elaboration-DAT Lit.: Our ancestors they.made.it.happen ... natural stones’ refinement ‘Our ancestors used to refine stones.’ 18. a. *čven-i c’inap’r-eb-is mier -a-xd-en-d-nen ... bunebriv-i kv-eb-is damušaveba-s. our-NOM ancestor-PL-GEN by 3BDAT.SG-PRV-happen-CAUS-IMPERF3ANOM.PL ... natural-NOM stone-PL-GEN elaboration-DAT ‘The natural stones used to be refined by our ancestors .’ b. *čven-i c’inap’r-eb-is-gan -a-xd-en-d-nen ... bunebriv-i kv-eb-is damušaveba-s. our-NOM ancestor-PL-GEN-from 3BDAT.SG-PRV-happen-CAUS-IMPERF3ANOM.PL ... natural-NOM stone-PL-GEN elaboration-DAT ‘The natural stones used to be refined by our ancestors.’ However, the situation is different with unaccusative verbs, which take only the theme argument and do not subcategorize for the agent role as such. When put in the construction with the inflected intransitive light verb -xd-, such verbs do get an interpretation with an implied agent. For instance, the unaccusative verb form ga-i-žon-a in (19a) does not take an agent but rather a theme argument. However, the corresponding analytical construction with the inflected intransitive light verb moxda allows both interpretations — with and without the agent (19b): 19. a. rogor ga-i-žon-a c’q’al-i? how PV-PRV-leak-3ANOM.SG.AOR water-NOM Lit.: How it.leaked.out water? ‘How did water leak out?’ In: Rudolf Muhr (ed.) (2006): Reproduction and Innovation in Language and Communication in different Language Cultures / Reproduktionen und Innovationen in Sprache und Kommunikation verschiedener Sprachkulturen. Wien u.a., Peter Lang Verlag. S. ‘How did water leak out (*by him/her)?’ b. rogor mo-xd-a c’q’l-is gažonva? how PV-happen-3ANOM.SG.AOR water-GEN leakage.NOM Lit.: How did of.whater leakage happened? ‘How did a water leak occurred?’ (it leaked out by itself) ‘How did a water leak occurred?’ (it leaked out because of somebody; somebody made it possible that the water leaked out) Thus, even if a synthetic verb form cannot subcategorize for an agent as such (19a), the corresponding analytic construction with the intransitive light verb -xd- allows an interpretation that implies the existence of an agent (19b). To summarize, while in Russian the main purpose of the proizojti / proizvesti construction is to defocus or distance the agent from the action, the facts of Georgian are more complex. Agent defocusing seems to apply to only a small subset of uses, and in other cases the agent is instead implicitly introduced to the action. 5. Discourse-Pragmatic Functions of the Analytical Constructions with the Inflected -xd- ‘happen’ and -xd-in/en ‘make happen’ Many nominals participate in the light verb construction even though they have a corresponding synthetic verb form. Although it might not always be clear from the translation, there is an important difference between the synthetic and analytical uses. Most of our examples with analytical constructions are taken from newspapers or from TV programs where the speakers tried to sound official, authoritative, politically correct, or scientifically correct. Although purists claim that the constructions are used exclusively by illiterate people5, in the media one finds many instances of such constructions that are neither ungrammatical nor ‘ignorant Georgian,’ but serve a specific need of the speaker — to assert (political or scientific) correctness and importance of the issue being discussed. An example of trying to sound official is in (20a), from a news report about a patient bitten by a dog. The phrase would sound ridiculous in normal conversation, but the journalist chose the analytical construction to avoid 5 See, for instance, the unsigned column in (sak 2004) dedicated to making fun of errors in TV broadcasting. There the author brings five examples of the use of the intransitive -xd- and notes that it has become almost a ‘universal’ verb. Probably the author meant that the analytical constructions with this verb can be used instead of almost any synthetic verb form. In: Rudolf Muhr (ed.) (2006): Reproduction and Innovation in Language and Communication in different Language Cultures / Reproduktionen und Innovationen in Sprache und Kommunikation verschiedener Sprachkulturen. Wien u.a., Peter Lang Verlag. S. specifying such details as the agent of the action and concentrate on the event itself as well as on its (grammatical) patient. 20. a. @mo-xd-a avadmq’op-is dapiksireba sak’ace-ze. PV-happen-3ANOM.SG.AOR patient-GEN attaching.NOM stretcher-on Lit.: it.happened of.patient attaching on.stretcher ‘The patient got attached to the stretcher.’ b. ekim-ma avadmq’op-i da-a-piksir-a sak’ace-ze. Doctor-ERG patient-NOM PV-3BNOM.SG-PRV-attach-3AERG.SG.AOR stretcheron Lit.: doctor patient (s)he.attached.him/her on.stretcher ‘ The doctor attached the patient to the stretcher.’ Other examples that sound official as compared to the corresponding sentences with a synthetic verb form are in (21a vs. 21b, 22a vs. 22b): 21. a. Uttered by Michael Saakashvili (the current president of Georgia), TV News on August 24, 2004 on the Georgian TV. @ruset-is sazgvar-tan mo-xd-a k’oncent’racia (t’eknik’-is). Russia-GEN border-at PV-happen-3ANOM.SG.AOR gathering.NOM techniqueGEN Lit.: of.Russia at.border it.happened gathering of.technique ‘At the Russian border military technique got gathered.’ b. ruset-is sazgvar-tan k’oncent’rir-d-a t’eknik’a. Russia-GEN border-at gather-INTR-3ANOM.SG.AOR technique.NOM Lit.: of.Russia at.border it.gathered military.technique ‘At the Russian border military technique got gathered.’ 22. a. @čven k’onk’urs-is c’es-it v-a-xd-en-t sasc’avlebl-ad gasagzavn-i k’ont’ingent’-is šerčeva-s. (Marsagishvili 2000) we.NOM contest-GEN rule-INST 1ANOM.SG-PRV-happen-CAUS- PLNOM6 studying-ADV to.be.sent-NOM contingent-GEN choosing-DAT ‘We make the choosing of the contingent to be sent for studying abroad by the way of contest.’ b. čven k’onk’urs-is c’es-it v-a-rč-ev-t sasc’avlebl-ad gasagzavn k’ont’ingent’-s. we.NOM contest-GEN rule-INST 1ANOM.SG-PRV-choose-TS-PLNOM studyingADV to.be.sent contingent-DAT ‘We choose the contingent to be sent for studying abroad by the way 6 The indices show the case of the argument triggering the particular agreement marker. In 22a the plural suffix -t is glossed as PLNOM, that is a plural marker triggered by the NOM argument. In: Rudolf Muhr (ed.) (2006): Reproduction and Innovation in Language and Communication in different Language Cultures / Reproduktionen und Innovationen in Sprache und Kommunikation verschiedener Sprachkulturen. Wien u.a., Peter Lang Verlag. S. of contest.’ The sentence in (23a), taken from an online collection of jokes, reflects a conversation between a woman who was raped and (probably) a correspondent who covers the story. The correspondent asks the question in (23a) with the analytical construction. Although the same question can also be asked with a synthetic form as in (23b), the joke includes the analytical version but not the synthetic one. 23. a. @rogor mo-xd-a tkven-i gaup’at’iureba? how PV-happen-3ANOM.SG.AOR your-NOM raping.NOM Lit.: How did your.PL raping happened? ‘How have you been raped?’ b. rogor ga-g-a-up’at’iur-es (tkven)? how PV-2BNOM.SG-PRV-rape-3AERG.PL.AOR you.NOM Lit.: How they.raped.you.PL you.PL? ‘How have you been raped?’ (24a) sounds authoritative and is meant to exert influence on the addressees. It is taken from an announcement displayed near the cathedral Svetitskhoveli in the ancient capital of Georgia, Mtskheta (see the August 2004 photo in the Appendix). The announcement concerned the production and sale of homemade candles by strangers outside of the cathedral. If instead of the analytical construction (24a) synthetic verb forms had been been used (as in 24b), the statement would have sounded like a simple narrative. 24. a. k’erz’o p’ir-eb-i -a-xd-en-en santl-is c’armoeba-s da xat’-eb-is damzadeba-s. private.NOM person-PL-NOM 3BDAT.SG-PRV-happen-CAUS-3ANOM.PL candleGEN producing-DAT and icon-PL-GEN making.ready-DAT Lit.: Private persons they.make.it.happen of.candle producing and of.icons making.ready ‘Unauthorized persons produce candles and make icons.’ b. k’erz’o p’ir-eb-i -a-c’armo-eb-en santel-s da -a-mzad-eb-en xat’-eb-s. private.NOM person-PL-NOM 3BDAT.SG-PRV-produce-TS-3ANOM.PL candle-DAT and 3BDAT.SG-PRV-make.ready-TS-3ANOM.PL icon-PL-DAT Lit.: Private persons they.produce.it candle and they.make.them.ready icons ‘Unauthorized persons produce candles and make icons.’ To summarize, the light verb constructions serve as a pragmatic tool to make utterances sound official, authoritative, and politically or scientifically In: Rudolf Muhr (ed.) (2006): Reproduction and Innovation in Language and Communication in different Language Cultures / Reproduktionen und Innovationen in Sprache und Kommunikation verschiedener Sprachkulturen. Wien u.a., Peter Lang Verlag. S. correct. The construction was influenced by Russian but developed in its own way, in accordance with other Georgian-internal factors.7 The next section explores a possible disambiguating function of the analytical construction. 6. Preserving Lexical Information Apart from the difference in pragmatics between the analytical and synthetic constructions, there is a difference in the use of preverbs. While synthetic forms lack preverbs in some TAM paradigms and leave certain lexical and/or aspectual information unspecified, the analytical constructions preserve such information. In an inflected verb form, the preverb often carries two kinds of information: aspectual (indicating perfective paradigms) and lexical (indicating a particular derivation from the basic meaning of the verb root), similar to the function of verbal prefixes in Slavic or German. When a masdar is used along with a light verb instead of an inflected verb, aspectual information may be expressed in two places: on the masdar and on the light verb. This potential redundancy makes it possible for the masdar’s preverb to specify its secondary lexical meanings and be present even in imperfective tenses. In (25a), the preverb is present and adds the information of re-doing the examination; in a synthetic construction (25b), it would be interpreted as marking perfectivity and Future tense, and is thus ungrammatical in the Present tense. It is possible to also add the preverb in 25b and make the synthetic form gada--amoc’m-eb-en express the same lexical nuance. However, the form with the preverb primarily occurs in the Future tense rather than Present. In present subseries (imperfective tenses), preverbs are normally absent and avoided unless it is an absolute necessity to express the lexical information coded in the preverb. In a light verb construction, aspectual information does not need to be specified on the masdar; the preverb is free to specify just the lexical information (25a). 25. a. @st’at’ist’ik’-is sammartvelo-s c’armomadgenl-eb-i mat xel-t arsebul-i inpormaci-is gada+moc’meba-s -a-xd-en-en. (axa 2001) 7 Although we do not know for certain how the analytical construction was borrowed into Georgian in the first place, Georgian culture seems to provide at least one possible pathway. Much cultural and linguistic knowledge in Georgia is transmitted via social networks rather than from official speeches and publications. In the tradition of supra, family patriarchs serve as tamadas, or toast leaders, during various celebrations (Mülfried 2005, Tuite 2005). The position of a tamada is very prestigious and a tamada’s behavior is often imitated. Party officials, whose speech was heavily influenced by Russian/Soviet speech patterns, were often invited to serve as tamadas at large celebrations. It is thus possible that officialsounding speech patterns spread throughout the general population through such celebrations. However, much more research is needed regarding the types of interactions and speeches given at supras to confirm this hypothesis. In: Rudolf Muhr (ed.) (2006): Reproduction and Innovation in Language and Communication in different Language Cultures / Reproduktionen und Innovationen in Sprache und Kommunikation verschiedener Sprachkulturen. Wien u.a., Peter Lang Verlag. S. statistics-GEN department-GEN representative-PL-NOM their hand-DAT.PL existing-NOM information-GEN re.checking-DAT 3BDAT.SG-PRV-happen-CAUS3ANOM.PL ‘Representatives of the Department of Statistics conduct a reexamination of the information available to them.’ b. st’at’ist’ik’-is sammartvelo-s c’armomadgenl-eb-i mat xel-t arsebul inpormacia-s -a-moc’m-eb-en / *gada--a-moc’m-eb-en. statistics-GEN department-GEN representative-PL-NOM their hand-DAT.PL existing information-DAT 3BDAT.SG-PRV-check-TS-3ANOM.PL PV-3BDAT.SG-PRV-checkTS-3ANOM.PL ‘Representatives of the Department of Statistics reexamine the information available to them.’ A similar case of lexical disambiguation is in (26a). 26. a. @rodis q’opila, an sad q’opila, kveq’n-is xelisupleba umaγles-i sasc’avlebl-eb-is sast’ip’endio pond-is lik’vidaci-is xarjze -a-xd-en-d-e-s biujet’-is gada+rčena-s? (Oniani 2000) when it.has.been or where it.has.been country-GEN government/officials.NOM higher-NOM educational.institution-PL-GEN for.stipend fund-GEN liquidation-GEN at.the.expense.of 3BDAT.SG-PRV-happen-CAUS-IMPERF-SUBJ-3ANOM.SG budgetGEN saving-DAT ‘Where or when has it ever been that the government/officials have saved the budget of the country at the expense of liquidating the stipend funds of the higher educational institutions?’ b. rodis q’opila, an sad q’opila, kveq’n-is xelisupleba umaγles-i sasc’avlebleb-is sast’ip’endio pond-is lik’vidaci-is xarjze -a-rč-en-d-e-s / *gada--arč-en-d-e-s biujet’-s? when it.has.been or where it.has.been country-GEN government/officials.NOM higher-NOM educational.institution-PL-GEN for.stipend fund-GEN liquidation-GEN at.the.expense.of 3BDAT.SG-PRV-save-CAUS-IMPERF-SUBJ-3ANOM.SG / PV3BDAT.SG-PRV-save-CAUS-IMPERF-SUBJ-3ANOM.SG budget-DAT ‘Where or when has it ever been that the government/officials have saved the budget of the country at the expense of liquidating the stipend funds of the higher educational institutions?’ We suspect that the disambiguation property of preverbs will play a major role in the further spread of the analytical construcitons with moxdoma / moxdena and in the speakers’ choice between the two options: analytical vs. synthetic. 7. Conclusions and Future Work We have described the emergence of an analytical construction using In: Rudolf Muhr (ed.) (2006): Reproduction and Innovation in Language and Communication in different Language Cultures / Reproduktionen und Innovationen in Sprache und Kommunikation verschiedener Sprachkulturen. Wien u.a., Peter Lang Verlag. S. moxdoma ‘happen’ or moxdena ‘make happen’ as light verbs to form complex predicates. This construction, while possibly triggered by a similar Russian structure, has been integrated into the morphosyntax of Georgian and is not merely a calque. In many cases, speakers have a choice between the newer analytical construction and an older synthetic one. In such cases, the analytical construction carries a sociolinguistic / pragmatic load that is (a) not predictable from its morphosyntax and (b) different from the function of the similar construction in Russian. It serves to make the speaker sound official or ‘correct’, politically or scientifically. Speakers seem to be aware of this functional load and sometimes take it too far, as demonstrated by examples in sections 4 and 5. However, much of the time the use of the construction succeeds in raising the officialness and prestige of what is being said, and the construction is steadily spreading into different domains of language use. We hope that our investigation has shown the futility of fighting against such innovations. Rather than condemning (or, for that matter, welcoming) the new linguistic structures, it is much more productive to study them and to examine how they interact with the existing language. For this purpose, real-life data is indispensable. 1 References (mer 2000): bunebrivi kvebi — tkveni mkurnali da mudmivi mparveli, meridiani 44, 2000. (The issue of May 17, available at: www.opentext.org.ge/05/sarbieli/107/107-28.htm, in Georgian). (axa 2001): tbilisši c’armoebuli realuri mšeneblobebis ricxvi dek’larirebuls orjer aemat’eba. axali ep’oka, 215. (The issue of August 7, in Georgian). (sak 2004): ‘ra utkvams, ra moučmaxavs...’ anu ek’ranuli kartulis ‘margalit’ebi’, sakartvelos resp’ublik’a, 41. (The issue of February 19, in Georgian). Marsagishvili, Sh. (2000): ra ušlis xels mušaobaši kartvel mesazγvreebs, axali ep’oka, 224. (The issue of August 16, in Georgian). Mülfried, Florian (2005): Banquets, Grant-Eaters and the Red Intelligentsia in PostSoviet Georgia. Central Eurasian Studies Review 4:16-19. Oniani, Dj. (2000): universit’et’i da sek’vest’ri? sakartvelos respublika 305. (The issue of November 19, in Georgian). Seriot, Patrick (1986): How to Do Sentences with Nous. Aanalyzing Nominalizations in Soviet Political Discourse. Russian Linguistics 10:33-52. Siamashvili, G. (2001): ‘me vieb sagnebs da mat cnobierebisagan damouk’idebel In: Rudolf Muhr (ed.) (2006): Reproduction and Innovation in Language and Communication in different Language Cultures / Reproduktionen und Innovationen in Sprache und Kommunikation verschiedener Sprachkulturen. Wien u.a., Peter Lang Verlag. S. arsebobas vanič’eb’ (gert’ruda st’aini: igive sit’q’vebi gansxvavebul k’ont’ekst’ši), dilis gazeti, 15. (The issue of September 6, in Georgian). Tchanturaia, M. (2001): ent’oni st’ori lesli čemberlenis c’ignze: ‘paruli xelovani: zigmund proidis gamoc’vlilviti k’itxva’, axali 7 de, 7. (The issue of February 16-22, in Georgian). Toklikishvili, L. (2005): k’ot’e k’ublašvili — sasamartlo mapiis natlimama, axali 7 de, 26. (The issue of July 15-September 2, in Georgian). Tuite, Kevin (2005): The autocrat of the banquet table: The political and social significance of the Georgian supra. Conference on Language, History, and Cultural Identities in the Caucasus, Malmö University, Sweden, June 2005. (available at: http://www.mapageweb.umontreal.ca/tuitekj/publications/Tuitesupra.pdf) 2 3 Appendix. The candle sign The sign on the photo below was posted near the cathedral Svetitskhoveli in the ancient capital of Georgia, Mtskheta in August 2004. In: Rudolf Muhr (ed.) (2006): Reproduction and Innovation in Language and Communication in different Language Cultures / Reproduktionen und Innovationen in Sprache und Kommunikation verschiedener Sprachkulturen. Wien u.a., Peter Lang Verlag. S. 27. martlmadidebel mosaxleoba-s! k’erz’o p’ir-eb-i -a-xd-en-en santl-is c’armoeba-s da xat’-eb-is damzadeba-s. rogorc cnobil-i gaxda, es xšir šemtxveva-ši damzadebul-i-a magiur-i rit’ual-eb-is šesruleb-is pon-ze. aset-i santl-eb-is šec’irva-anteba sakartvelo-s martlmadideblur ek’lesi-eb-ši daušvebel-i-a. magiur rit’ual-eb-ze damzadebul santl-eb-s da xat’-eb-s sarealizacio-d abareben mat’erialur-ad mz’ime mdgomareoba-ši mq’op adamian-eb-s da iq’ideba ek’lesi-eb-is mimdebare t’erit’ori-eb-ze. am mk’rexelur-i kmedeb-is ak’vet-is mizn-it svet’icxovl-is sap’at’riarko t’az’ar-i k’rz’alavs t’az’r-is garet šez’enil-i santl-is danteba-šec’irva-s c’minda t’az’arši. mat, visac ar akvs šesaz’lebloba santl-is an xat’-is šez’en-is, šesaz’lebel-i-a usasq’idlod mis-i mieba, t’az’ar-ši dadgenil-i c’es-it. orthodox population-DAT! Private.NOM person-PL-NOM 3BDAT.SG-PRV-happenCAUS-3ANOM.PL candle-GEN producing-DAT and icon-PL-GEN making.ready-DAT. As known-NOM it.became, this.NOM frequent case/event-in made-NOM-COP magicNOM ritual-PL-GEN performing-GEN background-on. Such-NOM candle-PL-GEN sacrificing-lighting.NOM Georgia-GEN orthodox church-PL-in unacceptable-NOMCOP. Magic ritual-PL-on prepared candle-PL-DAT and icon-PL-DAT selling-ADV they.give.them.to.them material-ADV hard condition-in being person-PL-DAT and it.is.sold church-PL-GEN neighboring territory-PL-on. This sinful-NOM action-GEN preventing-GEN purpose-INST Svetitskhoveli-GEN of.Patriarch cathedral-NOM it.prohibits.it cathedral-GEN outside purchased-NOM candle-GEN lighting-sacrificingDAT holy cathedral-in. Those, who NEG (s)he.has.it possibility.NOM candle-GEN or icon-GEN purchasing-GEN, possible-NOM-COP for.free its-NOM getting.NOM, cathedral-in established-NOM rule-INST Lit.: [To.]orthodox to.population! Private persons they.make.it.happen of.candle producing and of.icons making.ready. […] ‘To the orthodox (Christian) population! Unauthorized persons produce candle and make icons. As it became known, this in most cases is made while performing rituals of [black] magic. Sacrificing and lighting such candles in the orthodox churches of Georgia is unacceptable. The candles and icons prepared during the rituals of magic are given to materially deprived persons to sell, and are sold on the territories of neighboring churches. In order to prevent this sinful action, the Svetitskhoveli Cathedral prohibits the lighting [and] sacrificing in the holy Cathedral of the candles purchased outside the Cathedral. For those who are not able to purchase a candle or an icon, it is possible to get it for free by the rule established in the Cathedral.’