Horse Burial in Scandinavia during the Viking Age

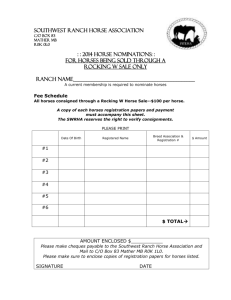

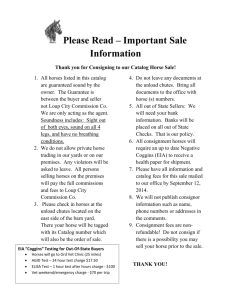

advertisement