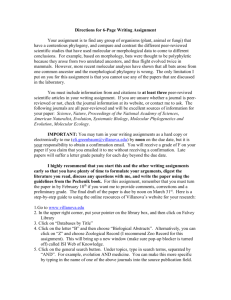

Directions for 2-Page Writing Assignment

advertisement

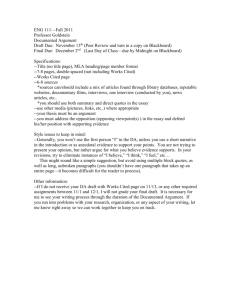

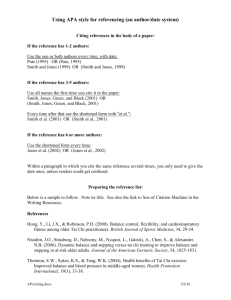

Directions for 2-Page Writing Assignment Your assignment is to read the article “Was Darwin Wrong?” by David Quammen from National Geographic (available at the National Geographic website or can be downloaded in Word format on the Evolution webpage), and answer the question in the title of the article. You are free to take either side of the argument, but because this is a course in Evolution and not religious studies, the majority of your arguments must NOT come from religious texts such as the Koran, Bible, or Torah. You must include information from and citations to at least two peer-reviwed scientific articles in your writing assignment. If you are unsure whether a journal is peer-reviewed or not, check the journal information at its website, or contact me to ask. The following journals are all peer-reviewed and will be excellent sources of information for your paper: Science, Nature, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, American Naturalist, Evolution, Systematic Biology, Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution, Molecular Ecology, Ecology, Animal Behaviour, Behavioral Ecology. IMPORTANT: You may turn in your writing assignments as a hard copy or electronically to me (eli.greenbaum@villanova.edu) by noon on the due date, but it is your responsibility to obtain a confirmation email. You will receive a grade of F on your paper if you claim that you emailed it to me without receiving a confirmation. Late papers will suffer a letter grade penalty for each day beyond the due date. I highly recommend that you start this and the other writing assignments early so that you have plenty of time to formulate your arguments, digest the literature you read, discuss any questions with me, and write the paper using the guidelines from the Pechenik book. I suggest you pick one argument that is discussed in the National Geographic article against Evolution, and then focus on this using data and information in the peer-reviewed literature. For example, you can provide evidence that Evolution is crucial to advances in medicine, and do a search for “evolution AND medicine” in the peer-reviewed literature. Here is a step-by-step guide to using the online resources of Villanova’s website to do this: 1.Go to www.villanova.edu 2. In the upper right corner, put your pointer on the library box, and then click on Falvey Library 3. Click on “Databases by Title” 4. Click on the letter “B” and then choose “Biological Abstracts”. Alternatively, you can click on “Z” and choose Zoological Record. This will bring up a new window (make sure pop-up blocker is turned off) called ISI Web of Knowledge. 5. Click on the general search button. Under topics, type in search terms, separated by “AND”. For example, evolution AND medicine. You can make this more specific by typing in the name of one of the above journals into the source publication field. 6. When you find an article that interests you, click on the blue “Find It” button to get to an electronic PDF. If the library does not have electronic access to the article you want, I do not recommend that you request the article through interlibrary loan unless you have plenty of time to wait—some of my requests from rare journals take weeks or even months to fill. Below are some excellent writing suggestions taken from Dr. Curry’s writing enriched classes: Do NOT follow Pechenik (2007:136-137) regarding specific details of format (page layout and citation style) for your Critique. Most importantly, we do NOT want to see the bibliographic information for your source at the top of the page. Rather, you must cite each source within the body of your essay, using the author+year format, and then list the bibliographic information in a terminal Literature Cited section (as Pechenik explains for Term Papers; his chapter 8). Format: Organize each of your papers exactly as shown below. Cover pages are NOT necessary; instead, show your last name and initials in the upper left-hand corner of the first page, and also include page numbers in a header on all subsequent pages (see Pechenik 2007:13, rule #23). Next, show the submission date, and the assignment name. Then, skip a few spaces, show your essay’s title (your own title, not the one from the published source), then start the “body” of your text. Here’s an example: Jones WG (your name) 10 Oct 2006 Introductory Ecology: Review Essay New studies of peatlands reveal a methane menace (←always include your own title) Methane is a natural gas that is part of the natural carbon cycle (Ricklefs 2007:148). Methane is also one of several gases implicated as a major cause of global warming (reviewed by Doe 1990). Smith and Hunt (2003) recently studied peat bogs in Ontario to determine whether … In this paper, I will address the question of whether Smith and Hunt’s recent findings … Smith and Hunt sought to investigate the role of … (etc., etc. … to end of essay) Literature Cited Doe, J. 1990. Global warming. Second edition. Oikos Press, Orlando, Florida, USA. Smith, Q. Z., and D. G. Hunt. 2003. Methane from Ontario peat bogs is incredibly nasty stuff. Ecology 81:3-23. Ricklefs, R. E. 2007. The economy of nature. Fifth edition. W. H. Freeman, New York, New York, USA. Note: The alphabetized Literature Cited list comes at the end of the paper. It does NOT have to start on separate page (for this course), but it MUST match exactly the format of journal Ecology (Ecological Society of America). See page 12 of this handout for details about that bibliographic format. When in doubt about format details for any particular category of reference, copy an example from a recent issue of the journal Ecology. Files in MS Word format are preferred (this is the University-supported word processor); please always name files using extension *.doc. All assignments for lecture and lab (even those submitted as hard copy) must be typed or word-processed. Double-space all text, including the reference list. 1) Name each file you submit beginning with your last name and then the assignment, e.g., Smith-Review. (Please don't make us open every file to figure out whose it is!) Show your name at the top of every page of each assignment; in a word processor, do this by adding a “header.” Number all pages, using either a header or footer. To help you with formatting details, there's a template file in Microsoft Word format on the course WebCT site. Open and then modify this file with your own material before renaming a copy as indicated above and then submit. 2) Save a COPY of every paper or computer file for yourself, preferably on your primary disk (e.g., your own personal computer) and on a backup disk. Protecting your own information stored electronically (or on paper) is something for which modern students (and practicing biologists) must take responsibility. You have a responsibility also to save your drafts and notes, too (see Pechenik 2007, chapter 2); doing this will protect you against any doubts we might raise about your sources. • Use a serif typeface/font like this (best ones: Times or Garamond), but not like this (a sans-serif font, such as Arial, Tahoma, or Helvetica). The little extensions of the letters that define a serif font make it easier to read in large blocks of text, as in an essay; use the sans serif fonts for graphics and projected stuff (e.g., PowerPoint). Writing Center We encourage you to seek help from the Writing Center (202 Old Falvey Hall). The consultants there may not be able to comment on the scientific substance of your assignments, but they can assist you especially in organizing and revising papers and in ‘cleaning up’ grammatical problems. Don’t lose points because you failed to get the help that was readily available! Academic Integrity We expect all students to adhere strictly to principles of academic honesty. This includes all aspects of submitting assignments, including actions involving the computers. We can only give you all the credit you deserve if we can tell how much of the work is uniquely yours. When in doubt about whether you are citing sources adequately or correctly in terms of format, just ask! We are here to help you learn how to do it right. Then what? The top priority for your essay is to summarize and explain the scientific content of your chosen article in your own words (i.e., you need to more than to just paraphrase the article’s Abstract). Your presentation must demonstrate that you have developed a solid understanding of the article's context, objectives, methodological approach, results (yes, the data, as displayed in their tables and figures, and the associated analyses, which you should describe verbally (do not copy and paste the tables and figures from the source article)), conclusions, and implications. The last bit involves your thoughts. Evaluation of Papers Below is an outline of the factors I will take into consideration in assigning your final grade on your Critique, with a comparable grading scale applied to other assignments. Grade: C Paper satisfactorily (but minimally) meets expectations of the assignment. It directly addresses a question or issue relevant to the scope of the course, with adequate reliance on appropriate biological literature sources. It presents a logical argument with a clear statement of your central objectives; develops an argument that incorporates accurately reported information from primary literature sources; and reaches a clearly explained conclusion that follows logically from that argument. The argument is developed by an organized sequence of main points and supported by specific details and examples. The text is readable and relatively free of errors in syntax, grammar, spelling, usage, punctuation, and requested format. Grade: B Paper fulfills all of the requirements of a “C” paper and, in addition, presents a central argument that is well thought out and shows careful analysis of hypotheses and evidence in the biological literature. The argument demonstrates original and critical thought in synthesis and analysis. Points of interpretation are soundly and thoroughly argued. Supporting evidence is strong and extensive. Text contains few errors. Grade: A Paper fulfills all of the requirements of a “B” paper and, in addition, presents an argument that is outstanding in its clarity, logic, rhetorical skillfulness, and originality. It demonstrates that you have a thorough understanding of the paper’s topic and an ability to apply and communicate that understanding through excellent writing. Grade: D Paper makes an attempt to address the issue or question posed, but has one or more serious problems: it lacks a central thesis; it fails to develop a consistent, logical, well-organized argument; details are inaccurate or few; the text is difficult to read because of multiple errors. Grade: F Paper contains no central question or problem, or it makes no attempt (or a fake attempt) to address a stated question. The paper fails to develop an argument of any sort. The text is filled with errors. The paper shows little or no indication that the author attempted to meet the expectations of the assignment, or to follow directions. A paper that contains any plagiarized material, that fails to incorporate adequate acknowledgment of all sources, or that otherwise violates the standards of academic integrity established by the University, Department, and instructor will receive a grade of “F” — and trigger disciplinary procedures that can result in failure (F) for the entire course … and even expulsion from the University. Anticipating and Avoiding Common Problems in Biology Writing Please follow the advice in this section; see also cited pages and sections in Pechenik (2007) There’s a lot you can do to minimize the amount of ‘editorial’ criticism you are likely to receive from your us…if you can learn to avoid problems that crop up frequently when students first start writing about biology. This will make your life easier—and then we can all concentrate on what you’re saying, rather than how you’re saying it. For starters, read “The Keys to Success” in Pechenik (2007:5-14); see also his chapter 6 about revising. Pechenik puts this list at the beginning of his book specifically to help students become aware of mistakes and misconceptions of which they may not even be aware. With the same goal, here we list some of the problems and issues that we encounter most frequently; all are discussed in Pechenik (2007) in detail. Omit ALL unnecessary words. Write as if every word cost you money (sometimes it does!). Strive for the simplest and most concise wording you can dream up. This will nearly always also be the easiest to understand! Do NOT use a jargon-heavy, formalized style with the (erroneous) thought in mind that such a style is appropriately ‘scientific’; write instead more like the way you’d talk. Note: Just because many papers in the scientific literature are written with a verbose style, this doesn’t make them good! Active voice and first person. Use these! It’s perfectly OK … really! There’s logic behind this advice (Pechenik 2005:104-105). The passive voice tends to be weaker than active. It is simpler and more direct to say, “Smith (1990) studied birds and found…” (active) instead of, “A study by Smith (1990) was done on birds. Patterns were found…” (by whom? The reader must infer needlessly; if they guess incorrectly, it’s the writer’s fault!). Using the active voice will almost always make your writing clearer and more concise. It is more effective to say, “I disagree with Jones’s conclusion because…” (no doubt about who disagrees) instead of “Jones’s conclusion could be questioned…” (by whom—you or someone else?? Again, don’t make the reader guess!) Take credit for your ideas! Paragraph construction. Strong ¶s can greatly improve your clarity and organization. We advocate starting each ¶ with a clear ‘topic sentence’ that states the ¶’s most important concept. The rest of the ¶ then supplies additional, supporting information the reader needs to know to understand or believe the topic sentence. If you want to introduce a new idea, start a new ¶. When reading a paper written this way, your audience can follow the flow of your argument (and your organization) from the topic sentences alone, which makes it easier to see the relevance and integration of everything else. Direct quotation: avoid including these in your writing most of the time. To show that you understand the meaning of what you’ve read, rephrase the author’s statements in your own words, followed by acknowledgment of your source (using an author+year text citation, or wording that links your sentence to a previous citation). Semicolons and run-on sentences. If you use a word like however in the middle of a sentence, it usually needs to be preceded by a semicolon to avoid a run-on sentence (i.e., one that combines two independent phrases, each of which should stand separately). Correct: “Many birds migrate after breeding; however, chickadees stay in the same area year-round.” Incorrect: “Many birds migrate after breeding, however chickadees stay…” (run-on with or without the word however). In short, you should not use however (or therefore or nevertheless) in place of but. Data should be used (always!) as a plural word by practicing biologists (even though ‘data’ often used as a singular term by journalists and computer people). These data, not this data. Scientific names (Latin binomials) should be italicized or underlined (always!). This applies to field notes, essays, exam responses, …the works. When referring to a species, always include both the genus and species names (never the species alone); it is also OK to refer to just the genus, if that’s what you mean. Example: Canis lupus (the gray wolf), or all dog-like beasts in Canis. You may abbreviate the genus name in a binomial…but only after you’ve written it out in full previously at least once. Therefore, a paper that refers only to E. coli (without ever writing out the generic epithet) is written sloppily—even though most biologists know that the E. stands for Escherichia. “Indirect” citations. Did you find and read every paper you cited? If you did not (and instead based your citation on information from somewhere else that was mentioned in the papers you DID read), then you must make it clear that you’re making an indirect citation— because the reader needs to know that your references of this sort are ‘second-hand’ (i.e., you have to take your primary author’s word for what the other papers said). The way to do this is something like: “Deer don’t eat leaves of this tree (Jones 1982, in Smith 1992).” The preceding sentence tells the reader that your account is based on Smith’s description of Jones’s conclusion. If your text includes an indirect citation, you MUST list BOTH papers in your literature cited list (even though you didn’t read Jones [1982]). But do you really need to mention all those sources that you only know about indirectly? Usually the answer is, “No, not really.” In many cases, you can base your text on the words of the authors that you DID read, but indicate that their coverage relied on older stuff by saying something like, “Lots of studies have shown that birds can fly (reviewed by Jones 1997).” This wording (especially the phrase “reviewed by”) indicates that the generalization wasn’t based solely on Jones’s own work, but on previous work (possibly including some by Jones). If your readers are interested in these older sources, they know where to look: in the reference list of Jones (1997). As long as you have established the “paper trail” leading to the various sources backing up your text, you’ve done your job. Other common grammar and style problems Please also read the sections in Pechenik (2007) cited below to avoid other errors that are common in student writing. Avoiding these errors will not only improve your writing … but will also impress medical or graduate school admissions folks, or prospective employers!!! That/Which. Don’t use ‘which’ when you should use ‘that’ Effect/affect. Learn the distinction It’s/Its. It’s serves as a contraction of “it is.” Its is the possessive pronoun (referring to something belonging to “it”). Don’t mix these up. i.e./e.g. These have two quite different meanings et al. Use when writing an author+year text citation for a source with >2 authors. The word ‘et’ (Latin for ‘and’) is not an abbreviation, so it should not be followed by a period; ‘al.’ is an abbreviation for alii (Latin for ‘others’), so it should be followed by a period Citation Details, using format of journal Ecology: Use this EXACT format!!!! I. Style for referring to sources in text of your paper: Journal Article or Book Chapter (treat latter like journal article): “Drought has little effect on corn (Smith and Jones 1993)” OR “Smith and Jones (1993) found that corn seedlings can survive drought.” Book (place colon and page number[s] after year to refer to specific page or section) “Changes in bog communities over time exemplify succession (Ricklefs 2001:526).” Note that the author+year combination is short-hand that refers to a specific published source; you can (and often should) use the combination as the subject of the sentence…but when doing so, always keep the author’s (or authors’) name (or names) and the year together. More on next page… II. Format for listing cited sources in terminal Literature Cited list: Journal article: in itia ls o nly, with sp ace s be tween comma here articl e ti tle (no " " or i tali cs; all words except 1st LOWER CASE) in itia ls be fore surname for • 2nd author Smith, A. C., and B. G. Jones. 1993. Effect of drought on corn growth. Ecological Monographs 58:250-273. Journa l ti tle (NOT ab breviated a nd NOT italicized/unde rline d) volu me n umbe r (is sue numb er NOT ne eded ) pa ge n umbe rs Entire book (e.g., if you cited pages from Ricklefs [1993]): au thors hip listed sa me a s fo r jou rnal bo ok titl e (no ita lics, a nd a ll word s except 1st LOWER CASE) Pub lish er, city, cou ntry Ricklefs, R. E. 1993. Economy of nature. Third edition. Freeman, New York, New York, USA. Note tha t reference i n Li terature Cited l ist does NOT includ e pa ge n umbe rs; m enti on those onl y in text citation Chapter from an edited book (with different authors for each chapter): au thor of chapter, li sted sam e as for jo urnal chapter title (like j ourna l pa ges of in itia ls o f 1s t ed itor articl e ti tle; no ital ics ) cited ch apte r onl y be fore surna me Jones, B. G, and Smith, R. E. 1990. Energetic efficiency. Pages 35-90 M. Doe and Q. R. Esposito, editors. Physiological ecology. Second edition. Methuen, London, England. bo ok title (like full book; n o italics) sa me a s fo r ful l bo ok in F.