NB: Benjamin citations are from _Illuminations_ Ed

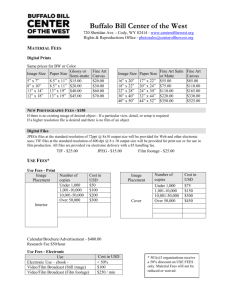

advertisement

NB: Benjamin citations are from Illuminations Ed. Hannah Arendt. Trans Harry Zohn. NY: Schocken, 1969. I’ve included a *brief* summary of Sobchack’s “Phenomenology and the Film Experience” as I rely my arguments on some of her theories. In section VIII, Benjamin writes that “the film actor lacks the opportunity of the stage actor to adjust to the audience during his performance,… This permits the audience to take the position of a critic, without experiencing any personal contact with the actor” (228). There is a certain truth to this, of course, but I would like to examine it using Vivian Sobchack’s work with phenomenology and embodied vision to consider the interaction that takes place between film and spectator. The “actual” content of a film does not change in the course of its screening, however, the spectator’s reaction to and interaction with the film alters what she perceives in, for example, the characters depicted. The viewed object (character / film) is thus empowered with responsiveness and, in turn, through this responsiveness interacts with the spectator. Such an interaction refuses the inevitability of a “distracted” or “habitual” identification with the camera, as Benjamin suggests of the spectator’s viewpoint, but offers a fluid interchange of position between subject and object. This theory would appear to require the autonomy of the spectator as maintaining an individual – phenomenological – experience / perspective. Can it work in agreement with Benjamin’s theory of the mass produced response? A central focus in phenomenology is that experience and consciousness of the I occur only relative to the Other. “Isolation” of experience from something external to that experience thus would not seem to be within the realm of consciousness. Rather than refute, this philosophy fully supports Benjamin’s claim that “individual reactions are predetermined by the mass audience response they are about to produce, … The moment those responses become manifest they control each other” (234). As I interact with a film as subject/object, I also know my experience through the Other – both the film and other spectators, who all contribute to my experience. Benjamin’s claim that individual reactions and reactions en masse are intertwined does not remove the individual experience from the spectator, but rather demonstrates that the very drive of mass culture is found in its being a shared commodity. Benjamin explains the film experience in terms of one’s experience of architecture, claiming that our perception there is two-fold: visual or “contemplative” and tactile or “distracted,” “habitual,” use based. He describes the tactile perception as one that through its distracted nature and by virtue of familiarity allows for an “absent-minded” viewer nonetheless to be consciously engaged in the experience of a film. Borrowing from phenomenology the idea that consciousness is an inherent carrier of meaning, we can understand habitual use as active perception, for through consciousness no experience is passive. One’s Palmer 2 experience of a film is primarily visual, and thus there need be no divorce of the visual, contemplative perception from the tactile, habitual perception of film. How does the “doubly visual” perception of film compound or multiply the contemplative experience? Can it refuse the “absent-minded” label? Considering visually-based habitual perception in terms of mass culture, what does it mean for any sort of perception to be “contemplative”? I think it is through consciousness of one’s experience that contemplation, which is equally instantaneous as absent-mindedness, is defined. One’s interaction with a film, as well as with the numerous neighboring Others whom one experiences primarily through nonvisual means, cannot be other than immediately present and, in keeping with the terms of the discussion, “active.” ***Sobchack, Vivian. “Phenomenology and the Film Experience.” Viewing Positions: Ways of Seeing Film.Ed. Linda Williams. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers, 1997, 36-58. In “Phenomenology and the Film Experience,” Sobchack relies on the teachings of phenomenology to explain the filmic experience, which she argues relies on the participants’ “mutual presupposition” of intersubjectivity and the intelligibility of embodied vision by those participants, i.e., filmmaker, film, spectator (38). Thus, it mimics human experience, which is defined by the relation of the I to the Other. Based on this premise of the nature of film, Sobchack calls for a “semiotics and hermeneutics of the cinema” that would “radically reflect on the origins of cinematic communication in the structures and pragmatics of existential experience” (39). It is important for her that this method recognizes as does phenomenology that meaning is inherent in existential experience by virtue of consciousness. Under the subheading “Film Theory and the Objectification of Embodied Vision,” Sobchack deconstructs alternate theories of film to show how they fall short of a semiotics of the cinema. Classical film theory employs two metaphors: the window, which shows film as “perception in itself” and relies on the role of the camera to reveal; and the frame, which shows film as “expression in itself” and relies on the role of the camera to control. Contemporary film theory moves beyond perception vs. expression with the metaphor of the mirror and “collapses” the two perspectives into a “synthesis of the refractive, reflexive, and reflective” (46-47). Sobchack’s primary difficulty with all of these theories is the premise that a film is a ‘viewed object,’ one without its own subjectivity. Sobchack closes her argument with a description of her own filmic experience as existing in a two-way exchange with the film. She does not provide support from others who share her experience, presumably Palmer 3 because her phenomenological methodology assumes the validity of the individual experience and denies the necessity of corroboration to prove it as such. Thus, Sobchack uses her experience to defend conclusively her insistence that film scholars return to origins of meaning in the cinema as found in the “systemic act of viewing” (55).