The Draft - U

advertisement

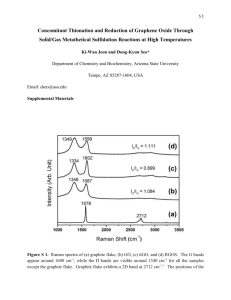

DRAFT Project: Probing the Smaller Web: Participation in Regional Organizations Principal Investigators: Kathy Powers (klp18@psu.edu), Petra Roter (petra.roter@fdv.unilj.si), Zlatko Sabic (Zlatko.Sabic@fdv.uni-lj.si), and Thomas Volgy (volgy@u.arizona.edu). Project participants: Ana Bojinovic (ana.bojinovic@fdv.uni-lj.si), Katharine Peterson (katharin@email.arizona.edu ), Elizabeth Fausett (elfauset@email.arizona.edu ) Stuart Rodgers (srodgers@email.arizona.edu ) Introduction: Although the development of modern international governmental organizations (IGOs) can be traced back to the beginning of the 19th century (Jacobson, Reisinger, and Mathers, 1986), their growth has been markedly spectacular over the last hundred years. Particularly after the end of World War II, and accelerating across the remainder of the 20th century, international politics witnessed the creation of what one scholar (Haas, 1970) dubbed the “web of interdependence”: a growing web of global international organizations and regimes, ranging from universal, multipurpose international organizations (i.e., the United Nations) to narrow, technical, functional organizations (e.g., International Atomic Energy Agency). 1 Much has been written about what we call here the global architecture that encompasses not all but a very significant portion of relations between states. Far less, however, has been written about the development of regional webs: architecture encompassing a broad range of regional governmental organizations (RGOs), many of which either vie with or complement the global web. Apart from the extensive focus on the European Union and theories associated with that region’s unique experience, the literature has emphasized the salience of regional trade agreements (RTAs) and regional economic structures (e.g., Choi and Caporaso, 2002), but has not systematically examined the broader contours of regional architecture outside of Europe.2 1 This project focuses on regional and global architecture in terms of actual, concrete, intergovernmental organizations, as opposed to international (and regional) regimes. There is obviously much overlap between the two (see Snidal, 1990; Keohane and Murphy, 1992), and ample literature on both (for details about international regimes see, among many others, Krasner, 1983; Haggard and Simmons, 1987; Young, 1989; Rittberger, 1990; Levy, Young and Zürn, 1995; Rittberger, 1995; Hasenclever, Mayer and Rittberger, 1997). The study of both formal organizations and international regimes, represent different analytical foci in studying the phenomenon of international governance as suggested by Kratochwil and Ruggie (1986:755). Having been associated with the process of international governance, the concept of international regimes has been envisaged as “occupying an ontological space somewhere between the level of formal institutions on the one hand and systemic factors on the other” (Kratochwil and Ruggie, 1986:760). However, the concept of international regimes has been surrounded by a lack of clarity since its introduction into the IR discourse in the 1970s and 1980s (Strange, 1983). Additionally, several problems in the practice of regime analysis have been pointed out, above all the subjective ontology (according to which regimes are based on convergent expectations among actors in a particular issue-area of international relations) that is inconsistent with, and contradicts, the positivist methodology, (Kratochwil and Ruggie, 1986:764-6; for a detailed account of different theories of international regimes, see Hasenclever, Mayer and Rittberger, 1997). 2 For the purposes of this project we assume that the EU represents (and will continue to represent for some time to come) a unique regional phenomenon in international relations, and as such, has received extensive academic attention. However, far less attention has been paid to the involvement of states within the broader European regional web (characterized by IGOs, such as the Council of Europe), or transatlantic institutions, There is little doubt that in terms of sheer numbers, the web of regional organizations is substantial and dynamic. For example, in the most recent systematic study of IGOs and state membership (Shanks, Jacobson, and Kaplan, 1996:598), by 1992 “geographic” organizations were 48 percent more prevalent than universal organizations, and over a 12 year period, grew at a rate 25 percent faster than universal ones. At the same time, geographical organizations were roughly three times more likely to “die” over the same time span than universal organizations. Survival rates varied widely by region, and such variation included death rates across groupings within Europe as well as outside the European region. Not unsurprisingly, the highest death rate was in the former “Eastern bloc” (86 percent), while American and African regional organizations exhibited “death” patterns below the average, and Asian and Arab organizations above the average (Shanks, Jacobson, and Kaplan, 1996:603). Our preliminary analysis of RGOs also indicates considerable regional variation and growth of these organizations (see Figure 1). Over the last two decades, RGOs mushroomed in Sub Saharan Africa, more than doubling in numbers, and especially over the last decade3. This is the opposite from Asia, where the last ten years witnessed a net increase of only one RGO, and the Middle East with no growth during the last time slice examined. As the table also illustrates, the Latin American (excluding Caribbean RGOs) and Sub Saharan regions account for nearly 70 percent of all RGOs outside of Europe. Given their numbers, and at the aggregate level the apparent variation in regional dynamics regarding both the survivability of RGOs and states’ involvement with them, we know all too little about why states join and participate in this segment of the international political system. In fact, the role of regional architecture in international politics and how it compares to global architecture is a little understood phenomenon among IR scholars. Regional architecture includes the complex network of connections through geographic proximity and dense institutional ties across regional institutions. These ties exist across a number of common political, military/security, economic, and environmental issues among member states. Global architecture—or as some refer to it universalism—refers to universal organizations whose membership constitutes potentially all states in the international system, such as the United Nations (UN) and the World Trade Organization (WTO). In principle—but not necessarily in practice—the UN Charter provides international law that guides how member states address mutual security issues (Bennett, 1995:233) through regional organizations4 while the WTO Agreement affords a similar service in international trade.5 Both universal organizations such as the Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe (OSCE) and the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) and within regional webs outside of Europe, and that is the central focus of our research. At the same time, we will map out as well the web for European states, and in fact will seek to determine the extent to which developments in Europe have impacted on regional webs elsewhere. 3 Our numbers differ somewhat from those of Shanks et. al. (1996), due to differences in definitions of RGOs and as well the use of data bases. Their calculations are derived from the Yearbook of International Organizations. We use the definition used by Russett, et al. (1998), and the COW criteria for identifying regional IGOs used by Pevehouse, Nordstrom and Warnke (2003) for their data base. Below, we explain why we prefer the Pevehouse et. al. approach in contrast to the definition used in the Yearbook of International Organizations. Nevertheless, we will replicate in our study both data bases in order to show that the results of our study are not a function of one definition as opposed to another. 4 As Bennett (2002:233) notes, however, the primacy of the UN Security Council over disputes under consideration by regional organizations has been substantially undermined. 5 Although the impact of GATT/WTO monitoring on regional organizations is also considered to be very small. For example, while RTAs that are recognized by GATT/WTO must be notified before they are entered into force, the GATT/WTO “working parties have had little success in bringing about changes to 2 specify the relationship between universalism and regionalism in their respective areas of governance. Yet, and despite clear global governance guidelines regarding the linkages between global and regional organizations, regional architecture has developed a life of its own, and offers an alternative context in which states can operate. Figure 1. Number of RGOs by Region, 1970-2000. 60 50 40 30 20 10 0 1970 1980 Sub Saharan Africa 1990 Asia Latin America Caribbean 2000 Middle East From a realist perspective on international cooperation, regional webs can thus play a crucial role for states to pursue their goals in an anarchical international system. From a liberal point of view, however, such regional webs can play a very different role – they can be perceived as providing a supplementary context for states to pursue their objectives. Theoretically, the existence of regional webs therefore poses at least two sets of questions: does regional architecture offer an alternative, or a supplementary, context in which states can operate? Put differently, what are the main motives for states to start cooperating with other states? Reflective of the second major IR debate (i.e. the neo-neo debate, see Baldwin, 1993 and Powell, 1994), the existence of regional webs and the choices states make when they establish these webs, or when they participate in regional institutions, can be explained with the concepts of relative and absolute gains (see Grieco, 1988; Keohane, 1989; Powell, 1991; Milner, 1992; Baldwin, 1993a). As an alternative context, regional webs could be used when states expect to gain more regionally in comparison to what they could gain at the universal level (so the prime motive for cooperation would be relative gains). By contrast, if regional RTAs agreements. It can only embarrass them into compliance”(Cohn, 2000:248). In Africa, the GATT/WTO enabling clause has recognized only about 10 percent of regional RTAs (Powers, 2001). 3 webs are indeed used supplementary (whereby the motives for state cooperation are absolute gains), then states may expect benefits at the universal and at regional levels. States have choices in joining and utilizing regional versus universal architecture in a variety of domains and policy areas, although there are concrete and subtle trade-offs to these choices. For example, regionalists argue that “regional organizations have a special capacity for controlling conflicts among their member states. By “making peace divisible,” regional organizations isolate conflicts and prevent solvable local issues from becoming tangled with irrelevant problems and thus changing them into insolvable global issues (Nye, 1971:17).” Regionalists further argue that geographic neighbors are more likely to understand the background of the conflict and shared norms about conflict management. Universalists counter that such a role for regional organizations is problematic for several reasons. First, geographic neighbors may be biased regarding the conflict. How can neutral intervention be guaranteed? In addition, regional organizations are rarely equipped with the resources necessary to quell the conflict (Nye, 1971). This research project is motivated by the puzzle involving the choices that states make regarding institutional context and international relations: Given the sheer proliferation of RGOs and IGOs, often within the same issue areas, why would states opt to be involved with the regional web of organizations, and is such involvement a preference for the regional over the global web of institutions? We will address this puzzle by pursuing answers to a set of more specific research questions: 1) Why is there substantial variation across states in their propensity to join the regional web? Is this variation consistent across all organizations or are there different explanations for why states may join some but not other organizations (e.g., security versus functional organizations)? 2) Is there a similar and substantial variation in participation inside the web once states have joined? Can we account systematically for variation in participation inside such organizations? If so, can we provide sufficient explanations for likely variation in participation among the joiners?6 3) What impact does joining and participating have on the states that are members of the regional web and involved in its myriad activities? Can we find patterns of impact on their foreign policy activities and/or their domestic political and economic activities? 6 We differentiate between what we call institutional and normative participation, with the former referring to states’ behavior within institutions (such as holding presidencies, special seats, fulfilling their budgetary obligations regularly, contributing additional financial resources for extra-budgetary activities, such as peacekeeping operations), and the latter to states’ support for existing norms (as shown in their signature and ratification of international treaties, adopted within the auspices of an international institution) and to the creation of new norms (e.g. their participation in the drafting of new politically and/or legally binding documents). Methodologically, however, such a distinction may prove problematic, particularly in the absence of the relevant data. We will seek to ascertain whether the data are available for each type of participation as this would add necessary information about the “quality” of states’ participation in international organizations, given that membership criteria appear very loose in most of international organizations. It is therefore very easy for states to join many organizations, but we know very little (see Finnemore, 1996; Linden, 2002) about how, if at all, states “use” their membership, or how states accustom their behavior to the normative context of international organizations once they have become full members. 4 4) In what ways (if any) do the patterns we uncover at the regional level constitute a dimension separate from joining, participating and being affected by the global web of organizations? Is it possible that the regional web merely replicates dynamics at the global level, or, does it provide alternatives to the global web and the dominance of great powers (and possible American hegemony) in the global web? 5) Have the developments at the regional level outside of Europe been produced by developments in Europe – in particular, has European integration caused (intentionally or unintentionally) competition in other regions in the sense that states in other regions have set up regional institutions, or have started to cooperate more actively at the regional level (as opposed to their participation in the global institutional web)? In sum, to what extent have regional webs developed as a result of the European integration? If this were the case, is it possible to think about a completely new form of hegemony, “institutional hegemony”, in the international system? Theoretical Orientation: Given the proliferation of global institutions, increased globalization (especially since the1980s), and the success of the EU, APEC, and NAFTA at the regional level, there is a rich and theoretically diverse literature on international institutions (Simmons and Martin, 2002), globalization processes (Zurn, 2002) and economic regionalism (Choi and Caporaso, 2002) and regional trade agreements and institutions (Mansfield, 1998). Yet, little of this literature has addressed the broader regional web that has been constructed in most regions, and has not addressed issues about why states would opt to join and to participate in varying degrees in the regional webs available to them. Since there is a paucity of literature on the four sets of questions noted above, this project will construct a research orientation based on a combination of inductive and deductive approaches.7 For example, we will examine empirically variation in joining RGOs both over time and across regions, and compare such variation to variation in joining global IGOs, and probe for patterns of similarities and differences across states, regions, and time slices across the ebb and flow of international politics. Our time frame will consist of a period cutting across both Cold War and post-Cold War epochs in international politics, and both during areas of high and low conflict, and high and low certainty. However, we will not be operating in a theoretical vacuum. In fact, there is a rich and diverse set of conceptual and theoretical tools—stemming from both the broader literature in international politics and the literatures on global institutions and regions—that will be adapted to the project. We will address the four sets of research questions (noted above) with the help of neorealist, liberal institutionalist, and strategic (combining domestic political concerns with policy preferences and power concerns) perspectives.8 This literature 7 We are similarly eclectic with respect to methodology: we will conduct our research using both quantitative data and qualitative case studies, where one methodological approach is more appropriate than another, although we will use both types of methods when we examine “outliers” (unique cases) and where we need substantial controls over explanatory conditions. 8 These perspective include as well the literature flowing from a “rational functionalist” perspective (Simmons and Martin, 2002). While we are not directly addressing the concerns of constructivists, the strategic approach, which focuses in part on the policy preferences and the domestic politics surrounding 5 overwhelming focuses on (and underscores major theoretical conflicts over) the impacts that international organizations have on members and on international politics. Thus, existing research, albeit often not directly addressing causes of joining behavior in the web of RGOs, can be used to provide salient clues regarding the range of conditions under which states may choose to enmesh themselves to varying degrees in regional and global webs. Consider for example some preliminary, empirical patterns we have uncovered to date: when we observe systematically the rates at which states join in RGOs across four time slices (1970-2000), we observe that: Patterns of joining in 1980 and 2000 are similar; different imperatives however seem to drive the propensity to join RGOs in 1970 and 1990; We note across every time slice substantial regional variation across the four regions: Latin America, Sub-Saharan Africa, Asia, and the Middle East. Although there appear to be some universally relevant predictors, each region yields substantially different combination of variables in accounting for joining. Although varying somewhat by region, two global patterns emerge across time slices and geographical areas outside of Europe: weakness in trade relations and weak economic capabilities are related to a greater propensity to join RGOs; likewise, prior patterns of joining seem to encourage more joining activity. Neorealist perspectives can help explain the consistency across the 1980/2000 time slices. Neorealists address well conditions (changes in polarity, polarization, and the distribution of power in the system) under which increasing uncertainty and higher levels of systemic conflict may impact on the ability and/or willingness of states to engage in a variety of cooperative behaviors (e.g., Gowa, 1989), including joining of RGOs. In a similar vein, neorealists may help us to explain the variation across regions: some of the inter-regional differences are likely to be due to the nature of system leaders and the states constituting these subsystems. Given American hegemony in Latin America, we would expect Latin American states to display patterns of joining different than states in SubSaharan Africa. The Middle East, a key focus of major conflict during and after the Cold War, and embedded in an ongoing Arab-Israeli conflict, has operated in a substantially different political context than Asia, and that context should have an impact on joining behavior. Asian states conduct their affairs within the context of major and contending political powers (and rapid changes in both military and economic capabilities of those powers), both residing in the region (China and Japan) and intruding from outside the region (U.S., USSR/Russia). These structural considerations are best addressed by neorealist approaches to international politics. Liberal institutionalists provide perspectives that may help explain the impact of initial joining on continued joining behavior. From this perspective, and regardless of why RGOs are initially created, involvement with regional webs should yield substantial benefits to states and particularly for those with limited resources. All else being equal, the costs of joining and participating in the web of RGOs should be more than offset by the benefits gained in increased information capabilities, expertise, and potentially increased levels of influence over the affairs of the region. One argument made by liberal institutionalists is that institutional structures provide predictability and reduce the costs of resolving myriad problems, leading to more successful foreign policy elites (Bueno de Mesquita, 2001) integrates both constructivist and domestic politics approaches to foreign policy explanations. 6 state outcomes, including for example generating more FDI and increased trade. Likewise, changing domestic political structures in a democratic direction also provide similar payoffs through greater transparency and predictability. Yet, since it is likely that for certain elites the costs of democratization are very high (loss of office); is it plausible that they are able to substitute (e.g., Most and Starr, 1984) participation in RGOs for democratization domestically?9 The strategic perspective will help us look at this tradeoff between domestic structural change and RGO participation, and will shed light on some of the preliminary findings showing that it is not necessarily the strong trading states that join RGOs. Our preliminary analysis suggests as well that there appears to be a negative relationship between the level of democratization and RGO joining for states in some regions. The fact that this relationship appears in some regions (e.g. Africa) but not others (e.g. Latin America) suggests as well the interaction between sub-systemic conditions and domestic stimuli, and appears to contradict literature focusing on the propensity of democratic states to join IGOs.10 Research Agenda: Answering fully the four sets of questions posed above will lead us to pursue the following research steps: 1) Delineate global and regional webs. This phase will constitute a systematic description of the creation, growth and decay of both global IGOs and RGOs in decade time slices, starting with 1970 and ending with 2000.11 We will document the numbers of organizations created, their areas of focus (security, economic, cultural, environmental, technological/functional), and document the extent to which organizational decay and growth intersect by areas of focus. We will undertake a similar inventory of RGOs, replicating both time slices and classification schemes employed for global IGOs. We will delineate RGOs both in the aggregate and by region,12 identifying RGOs that are primarily regional in scope 9 For an alternative argument indicating that it is RGOs that help nurture young demoncracies, see Pevehouse (2002). 10 Note for example robust findings at the aggregate level, showing that democracy promotes “higher densities of IGO membership” (Russett, Oneal, and Davis, 1998:461). 11 We will observe as well these webs for 2005 to determine if the 2000 pattern is changing in the post September 11, 2001 environment. However, the half-decade interval will not allow us to perform the same systematic comparison as with the earlier time slices. 12 We define region as a group of countries located in a geographically specified area with cultural, economic, linguistic and political ties (Mansfield and Milner, 1999), including membership in a UN General Assembly caucusing group. When a state is a member of more than one caucusing group, we define its appropriate region by determining where it locates itself with respect to its principal memberships in RGOs. Our focus is on the following regions: Sub-Saharan Africa , Middle East (including Morocco, Algeria, Tunisia, Libya, Sudan, Iran, Iraq, Egypt, Syria, Lebanon, Jordan, Israel, Saudi Arabia, Kuwait, Bahrain, Qatar, Yemen, United Arab Emirates, Oman), Asia (including 24 countries of the Asia-Pacific region: Afghanistan, Bangladesh, China, Mongolia, Taiwan, South Korea, North Korea, Japan, India, Bhutan, Pakistan, Myanmar, Sri Lanka, Maldives, Nepal, Thailand, Cambodia, Laos, Vietnam, Malaysia, Singapore, Brunei, Philippines, and Indonesia), Latin America (including South and Central America), the Caribbean, and Europe. In addition to regional membership, we will consider state membership in intercontinental but less than universal organizations, and consider as well the extent to which states balance their regional affiliations with not only involvement with the global web of organizations but as well with organizations outside their regions and organizations that are basically intercontinental in nature. 7 and as well those which have a single region as their dominant membership but allow additional members from other regions (i.e., extraregional organizations, such as OPEC).13 At the aggregate level, the delineation of global and regional webs will provide for us important background information for the tasks we need to pursue. Particularly from a strategic perspective, we will need to show the extent to which states have choices between four options: joining the regional web, joining the global web, creating a mixed strategy, or minimizing involvement in either web. This stage will allow us to observe the extent to which these webs complement or overlap with each other and, at the nation-state level, the range of choices available to states for the means with which they choose to pursue foreign policy objectives. 2) Delineate state membership: This phase of the project will pursue two concerns. First, we will identify the extent to which states join available regional organizations and thus, the extent to which they are embedded in the geographic web; second, we will undertake a similar analysis of their involvement in the global web.14 Once more, we will probe such joining behavior across four time slices, seeking to account for changes in joining over time, and across the changes occurring in international politics. At the same time we will seek to determine empirically the extent to which patterns of joining the regional and the global web are related to one another. It is plausible, for example that certain states are more likely to join global economic webs while opting to be less extensively involved in regional security webs. Alternatively, some states may view regional webs as a better focus of their activities than global webs. More likely, such decisions may be in significant part dependent on the degree of resources needed in each organization (and the resources available to states) to allow for a successful pursuit of foreign policy objectives. However, at this stage of research, we simply wish to show the extent to which states exhibit patterns of joining that would indicate the exercise of such choices. 3) Exploring regional joining behavior In this section we will address the puzzles uncovered by the data regarding a variety of correlates of states joining regional webs. Our initial empirical explorations, for example, have uncovered the following puzzles: For example, Australia and New Zealand (two states we could consider to be part of the Oceania region) have extensive memberships both in Asian and European RGOs. Others with similar patterns include Switzerland, Norway, and Japan. 13 An RGO exists when (following the Pevehouse/COW criteria): 1) Its membership is made up of states (in the COW defined state system); 2) It has a minimum of three states as members; 3) The IGO holds at least one regular plenary sessions every ten years; 4) The IGO possesses a permanent secretariat and corresponding headquarters; 5) Emanations—IGOs created by existing IGOs, as opposed to states creating IGOs—are not included as RGOs; 6) It is a REGIONAL IGO (RGO) when: a majority of its membership is from one region, and the headquarters of its secretariat is also from that region. 14 We are fortunate to be able to rely on existing databases for this effort. The global web, along with substantial regional components is observed annually through the Yearbook of International Organizations (2004). In addition, data on RGOs is available in annual observations through an archive made available by John Pevehouse and ICPR (see http://polisci.wisc.edu/users/pevehous/ and http://cow2.la.psu.edu/). . 8 “Time Slice Differences” There appear to be different sets of variables predicting to states joining RGOs in 1980/2000 than in 1970 and 1990. We will provide and test an explanation of this puzzle. We suspect that while the dynamics of regions account for substantial inter-regional variation in joining, some commonalities occur as a function of the global political context in which RGOs operate. The 1980/2000 time slices represent points in global politics of relatively low uncertainty and stability, compared to the other two time-points, and should provide a different opportunities and constraints for states than during periods of greater global uncertainties. We are also and especially interested in uncovering any potential changes in strategic calculations made by states regarding regional versus global webs in the aftermath of the post-Cold War period. While we obviously expect dramatic developments among the former Warsaw Pact states and for the newly independent states of the former Soviet Union, it is far less clear how strategic calculations outside of Europe regarding regional and universal architecture have been affected by the continued hegemony of the US in the post-Cold War environment. Much rhetoric exists among these states about finding alternatives to US leadership; whether such rhetoric has translated to a different pattern of architectural use since the end of the Cold War will be interesting to ascertain. “Regional Uniqueness” States in different regions exhibit different sets of predictor variables for joining their relevant RGOs, and confirming this, a regression model shows that each region (treated as a dummy variable) creates a significant impact on joining, regardless of the time slice examined. What is so unique about each region that different explanations are needed across regions for explaining joining behavior? Is there an underlying pattern that differentiates regions from each other, either in terms of their internal dynamics, or the manner in which these regions are embedded in the larger global political process? We will probe both sides of this puzzle. At a first, rough glance, it appears that part of the answer is about intrusion (the extent to which global powers have sought to control politics within a particular region), partially about the sporadic versus consistent levels of regional conflict (e.g., in the Middle East versus Asia)15, and partially about the nature of the states constituting the region (e.g., weak states more likely to seek additional resources through participation in RGOs). “Reversing Democratization Explanations” Much of the literature has argued that democratic polities are likely to join and participate in international institutions (e.g., Russett, Oneal, and Davis, 1998). This is presumably so since democracies exist with stable rules and practices, and relatively non-violent institutionalized rules for policy making and cooperation between political actors, akin to participation in international institutions. Yet, our preliminary analysis suggests that RGO joining is, if anything, negatively associated with level of democracy of the state in one or more regions.16 Why would there be a negative relationship between RGO joining and a state’s level of democratization? Borrowing from both liberal institutionalist and strategic perspectives, This assertion is consistent with Russett, Oneal, and Davis’ (1998:461) findings regarding the negative effects of military disputes on joining IGOs 16 By level of democracy, we are referring to 15 9 we will argue and seek to test that this finding is consistent with both strategic thinking among policy makers (unwilling to risk the consequences of democratization) and consistent with the purported benefits provided by such organizations. Societal pressures on state propensity to act within RGOs Liberal IR theory (Moravcsik, 1997) seeks to explain state behavior in world politics by analyzing state-society relations – i.e. “the relationship of states to the domestic and transnational social context in which they are embedded” (ibid.:513). States can change their behavior, following their changed preferences, as a result of societal ideas, interests, and institutions (ibid.). Changes in strategic calculations of governments, such as their decision to fulfill their goals regionally, or their decision to suspend their membership in a regional organization, can be a result of domestic developments that have affected the formation of state preferences for international cooperation. Some of our preliminary results may indicate that such societal pressures may be at work in some regions. For example, we find that inflationary pressures and what we call a misery index (combination of inflation and unemployment) may be related to a greater propensity to join RGOs in some but not all regions. Weak states (including weak trading states) join RGOs The literature suggests that regional trading is more extensive than global trading (Choi and Caporaso, 2002), even in regions outside of the EU. It would then make sense that states that trade extensively would be more likely to join the web of RGOs. Yet, we observe the opposite in a number of regions: either trade as a percentage of GDP is unrelated to RGO membership in some regions, or it is negatively correlated in others. A similar pattern appears with state capabilities (economic and military). Consistent with neorealist explanations and the strategic perspective, we will argue that there are two phenomena at work here. In some regions, the weaker the state and the less it is able to benefit on its own from global trading arrangements, the more likely it is to join RGOs in order to increase its capabilities and to benefit from regional trade and investment opportunities as an alternative to its inability to be extensively involved in global arrangements. In addition, weak states may engage in RGOs where there is a strong regional hegemonic presence either because the weak state cannot resist attempts by hegemonic powers to create structural arrangements; and/or weak states seek to increase their capabilities by “bandwagoning” on the heels of hegemonic states. 4) Exploring Patterns of Participation in the Regional Web Joining the regional web is not inexpensive for states nor is it likely to be without benefit. However, joining the regional web constitutes only one dimension of involvement, and even extensive joining across the range of regional organizations likely fails to reflect well the extent of actual participation and involvement within RGOs once states have joined in the web. Therefore, it is important to determine not only joining but also the extent of participation in the regional web, and as well to determine both the reasons for variation in participation and the impact that such participation has on states. Measuring actual participation and involvement in RGOs is of course much easier to propose than to accomplish. Creating valid measures of RGO participation appears to be an onerous task, and we are not aware of any systematic data presently available that we can adapt to this task. Therefore, we will need to develop conceptually sound, and empirically 10 valid and reliable measures of state participation in RGOs, and create the data base necessary with which to examine both inter-state and inter-regional variation in participation. There are a number of measures of participation we will consider.17 These include: 1) Variation in the size of state delegations to RGOs, based on the assumption that personnel are needed for participation, and the size of the delegation may at least reflect the determination of the state to participate more or less extensively in an organization’s deliberations; 2) Treaty signing: most organizations have multiple treaties used to take specific action or to augment the structure of the organization. Participation could be observed by number of RGO treaties signed. Particularly important would be the number of reservations (refusal to participate in an aspect of the treaty), indicating a reluctance to participate in the organization’s activities and objectives. 3) Participation in annual and regular meetings; 4) Presidencies, special seats (e.g. non-permenant seats in the UNSC); 5) Regular contributions to the budget of the organization 6) Additional financial contributions for special activities/tasks of RGOs. 5) Exploring the Impact of the Regional Web on Participants 17 See note 6. 11 References Abbott, Kenneth, and Duncan Snidal. 1998. “Why States Act Through Formal International Organizations.” Journal of Conflict Resolution 52:3-32. Baldwin, David. 1993 (ed.) Neorealism and Neoliberalism: The Contemporary Debate. New York: Columbia University Press. Baldwin, David A. 1993a. “Neoliberalism, Neorealism, and World Politics,” in David A. Baldwin (ed.), Neorealism and Neoliberalism: The Contemporary Debate. New York: Columbia University Press Bennett, A. LeRoy. 2002. International Organizations: Principles and Issues. Upper Saddle River, New Jersey: Prentice Hall. Berejekian, Jeffrey. 1997. “The Gains Debate: Framing State Choice.” American Political Science Review 91:789-805. Barnett, Michael N. and Martha Finnemore. 1999. “The Politics, Power, and Pathologies of International Organizations,” International Organization 53:699-732. Bueno de Mesquita, Bruce. 2001. Principles of International Politics. Buzan, Barry, and Ole Waever. 2003. Regions and Powers: The Structures of International Security. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Caporaso, James. 1992. International Relations Theory and Multilateralism: The Search for Foundations.” International Organization 46:599-632. Chan, Steve 2004. “Influence of International Organizations on Great-Power War Involvement: A Preliminary Analysis.” International Politics. 41: 127-143. Choi, Young Jong, and James A. Caporaso. 2002. “Comparative Regional Integration,” in Walter Carlsnaes, Thomas Risse, and Beth A. Simmons (eds.), Handbook of International Relations. London: Sage. Cohn, Theodore H. Cohn. 2003. Second edition. Global Political Economy: Theory and Practice. Second Edition. New York: Longman Collins, Alan. 2003. Security and Southeast Asia: Domestic, Regional and Global Issues. Boulder: Lynne Rienner. Cortell, Andrew P. and James W. Davis Jr. 1996. “How Do International Institutions Matter? The Domestic Impact of International Rules and Norms,” International Studies Quarterly 40:451-79. 12 Cupitt, Richard, Rodney Whitlock, and Lynn Williams Whitlock. 1996. “The [Im]mortality of Intergovernmental Organizations.” International Interactions 21:389-404. Duffield, John S. 1992. “International Regimes and Alliance Behavior: Explaining NATO Convetional Force Levels.” International Organization 46:369-388. Fawcett, Louise, and Andrew Hurrell. 1995. Regionalism in World Politics: Regional Organization and International Order. Oxford: Oxford University Press. Feld, Werner J., and Gavin Boyd (eds.). 1980. Comparative Regional Systems: West and East Europe, North America, the Middle East and Developing Countries. New York: Pergamon Press. Finnemore, Martha. 1996. National Interests in International Society. Ithaca/London: Cornell University Press. Foot, Rosemary, S. Neil MacFarlane, and Michael Mastanduno. 2003. US Hegemony and International Organizations. London: Oxford University Press. Gallarotti, Giulio M. 1991. “The limits of international organization: systematic failure in the management of international relations.” International Organization 45 (2): 183220. Goh, Evelyn. 2004. “The ASEAN Regional Forum in United States East Asian Strategy.” Pacific Review 17: 47-69. Gowa, Joanne. 1989. “Bipolarity, Multipolarity and Free Trade,” American Political Science Review 83:145-56. Grant, J. Andrew, and Fredrik Soderbaum. 2003. The New Reginalism in Africa. Aldershot: Ashgate Grieco, Joseph M. 1988. “Anarchy and the Limits of Cooperation: A Realist Critique of the Newest Liberal Institutionalism.” International Organization 42: 485-507. Grieco, Joseph M. 1997. “Systemic Sources of Variation in Regional Institutionalization in West Europe, East Asia, and the Americas,” in Edward D. Mansfield and Helen V. Milner (eds.), The Political Economy of Regionalism. New York: Columbia University Press. Grieco, Joseph, Robert Powell, and Duncan Snidal. 1993. “The Relative-Gains Problem for International Cooperation.” The American Political Science Review 87, 3: 729-743. Grugel, Jean and Wil Hout (eds.). 1999. Regionalism Across the North-South Divide: State Strategies and Globalization. London: Routledge. Haas, Ernst B. 1970. The Web of Interdependence: The United States and International Organizations. Englewood Cliffs: Prentice Hall. 13 Haftendorn, Helga, Robert O. Keohane and Celeste A. Wallender. 1999. Imperfect Unions: Security Institutions Over Time and Space. New York: Oxford University Press. Haggard, Stephan and Beth A. Simmons. 1987. “Theories of International Regimes.” International Organization 41(3):491-517. Hammer, C., and P. J. Katzenstein. 2002. “Why Is There No NATO In Asia? Collective Identity, Regionalism, and the Origins of Multilateralism.” International Organization 56:575-607. Hasenclever, Andreas, Peter Mayer and Volker Rittberger. 1997. Theories of International Regimes. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Hewitt, Joseph, and Jonathan Wilkenfeld. 1996. “Democracies in International Crises.” International Interactions 22:123-41. Holsti, K.J. 2004. Taming the Sovereigns: Institutional Changes in International Politics. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Hurrell, Andrew. 1992. “Latin America in the New World Order: a Regional Bloc of the Americas?” International Affairs. 68 1: 121-139 Ikenberry, John. 2001. After Victory: Institutions, Strategic Restraint, and the Rebuilding of Order After Major Wars. Princeton: Princeton University Press. International Monetary Fund. Various years. Direction of Trade. Jacobson, Harold K. 1984. Networks of Interdependence: International Organizations and the Global Political System. 2nd Edition. New York: Knopf. Jacobson, Harold K., William R. Reisinger, and Todd Mathers. 1986. “National Entanglements in International Governmental Organizations.” American Political Science Review 80:141-59. Katzenstein, Peter J., Robert O. Keohane, and Stephen Krasner. 1998. “ International organization and the study of world politics.” International Organization. 52: Keohane, Robert O. 1984. After Hegemony: Cooperation and Discord in the World Political Economy. Princeton: Princeton University Press. Keohane, Robert O. 1989. International Institutions and State Power: Essays in International Relations Theory. Boulder: Westview. Keohane, Robert O. and Lisa L. Martin. 1995. “The Promise of Institutional Theory,” International Security 20:39-51. 14 Keohane, Robert O. and Craig N. Murphy. 1992. “International Institutions,” in Mary Hawkesworth and Maurice Kogan (eds.), Encyclopedia of Government and Politics (Vol. I), 871-886. London/New York: Routledge. Kim, Sunhyuk, and Yong Wook Lee. 2004. “New Asian Regionalism and the United States: Constructing Regional Identity and Interest in the Politics of Inclusion and Exclusion.” Pacific Focus 19:185-231. Krasner, Steven. 1982. “Regimes and the limits of realism: regimes as autonomous variables,” International Organization 36: 355-368. Krasner, Steven. 1991, “Global Communications and National Power: Life on the Pareto Frontier.” World Politics 43:336-66. Kratochwil, Friedrich and John G. Ruggie. 1986. “International Organization: A State of the Art on an Art of the State.” International Organization 40:753-775. Lake, David. 1996. “Anarchy, Hierarchy, and the Variety of International Relations.” International Organization 50:1-34. Lavelle, Kathryn. 2004. “African States and African Interests: The Representation of Marginalized Groups in International Organizations.” Seton Hall Journal of Diplomacy and International Relations 4:111-124. Lawrence, Robert Z. 1996. Regionalism, Multilateralism and Deeper Integration. Washington D.C. Brookings Institution. Lemke, Douglas. 2002. Regions of War and Peace. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Levy, Marc. A., Oran R. Young and Michael Zürn. 1995. “The Study of International Regimes.” European Journal of International Relations 1(3):267-330. Linden, Ronald. H. (ed.). 2002. Norms and Nannies: The Impact of International Organizations on the Central and East European States. Lanham/Boulder/New York/Oxford: Rowman & Littlefield. Martin, Lisa and Beth Simmons. 1998. “Theories and Empirical Studies of International Institutions.” International Organization, 52:729-58. Mansfield, Edward D. 1998. “The Proliferation of Preferential Trading Arrangements.” Journal of Conflict Resolution 42:523-43. Mansfield, Edward D. and Helen V. Milner. 1999. “The New Wave of Regionalism.” International Organization 53:589-628. 15 Mansfield, Edward and Eric Reinhardt. 2003.“Multilateral Determinants of Regionalism: the Effects of GATT/WTO on the Formation of Preferential Trading Arrangements.” International Organization 57:4. Mattli, Walter. 1999. The Logic of Regional Integration: Europe and Beyond. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Mearsheimer, John J. 1994. “The False Promise of International Institutions.” International Security. 19, 3: 5-49. Mearsheimer, John J. 1995. “A Realist Reply.” International Security 20:85-93. Mitrany, David. 1966. A Working Peace System. Chicago: Quadrangle. Milner, Helen. 1992. “International Theories of Cooperation Among Nations. Strengths and Weaknesses (Review Article).” World Politics 44:466-496. Moravcsik, Andrew. 1997. “Taking Preferences Seriously: A Liberal Theory of International Politics.” International Organization 51:513-553. Most, Benjamin A., and Harvey Starr. 1984. “International Relations Theory, Foreign Policy Substitutability, and ‘Nice’ Laws.” World Politics 36:383-406. Narine, Shaun. 2002. Explaining ASEAN: Regionalism in Southeast Asia. Boulder: Lnne Rienner. Nierop, Tom. 1994. Systems and Regions in Global Politics: An Empirical Study of Diplomacy, International Organization, and Trade, 1950-1991. New York: Wiley. Nye, Joseph (1971) Peace in Parts: Integration and Conflict in Regional Organization. Boston: Little, Brown. Pevehouse, Jon C. 2002. “With a Little Help from My Friends? Regional Organizations and the Consolidation of Democracy, “ American Journal of Political Science 46:611626. Pevehouse, Jon, Timothy Nordstrom, and Kevin Warnke. 2003. "Intergovernmental Organizations, 1815-2000: A New Correlates of War Data Set." http://cow2.la.psu.edu/. Powell, Robert. 1991. “Absolute and Relative Gains in International Relations Theory.” American Political Science Review 85:1303-1320. Powell, Robert. 1994. “Anarchy in International Relations Theory: The Neorealist-Neoliberal Debate.” International Organization 48:313-344. Powers, Kathy L. 2004. Regional Trade Agreements as Military Alliances. International 16 Interactions 33 (4): Powers, Kathy L. 2001. International Institutions, Trade and Conflict: African Regional Trade Agreements from 1950-1992. Dissertation, Ohio State University. Rapkin, David P. 2001. “The United States, Japan, and the Power to Block: the APEC and AMF Case.” Pacific Review 14:373-410. Rittberger, Volker (ed.). 1990. International Regimes in East-West Politics. London/New York: Pinter Publishers. Rittberger, Volker (ed.). 1995. Regime Theory and International Relations. Oxford: Clarendon Press. Russett, Bruce, John R. Oneal, and David R. Davis. 1998. “The Third Leg of the Kantian Tripod for Peace: International Organizations and Militarized Disputes, 1950-85.” International Organization 52: 441-467. Shanks, Cheryl, Harond K. Jacobson, and Jeffrey H. Kaplan. 1996. “Inertia and Change in the Constellation of International Governmental Organizations, 1981-1992.” International Organization 50:593-627. Simmons, Beth A., and Lisa L. Martin. 2002. “International Organizations and Institutions.” Walter Carlsnaes, Thomas Risse, and Beth A. Simmons (eds.), Handbook of International Relations. London: Sage. Snidal, Duncan. Year. “Relative Gains and the Pattern of International Cooperation.” American Political Science Review 85:701-26. Snidal, Duncan. 1990. “IGOs, Regimes, and Cooperation: Challenges for International Relations Theory,” in Margaret P. Karns and Karen A. Mingst (eds.), The United States and Multilateral Institutions: Patterns of Changing Instrumentality and Influence. Boston/London/Sydney/Wellington: Unwin Hyman. Soderbaum, Fredrik. 2003. Theories of New Regionalism. London: Palgrave Macmillan. Strange, Susan. 1983. “Cave! Hic Dragones: A Critique of Regime Analysis,” in Stephen D. Krasner (ed.), Internationa Regimes. Ithaca: Cornell University Press. Triesman, Daniel. 1999. “Political Decentralizaiton and Economic Reform: A Game-Theoretic Analysis,” American Journal of Political Science 43:488-517. Union of International Associations. Various Years. Yearbok of International Organizations, 2004. New York: K.G. Saur. 17 Wallace, Michael, and J.D. Singer. 1970. “Intergovernmental Organizations in the Global System, 1816-1964: A Quantitative Description.” International Organization 24:239-87. Young, Oran R. 1989. “The Politics of International Regime Formation: Managing Natural Resources and the Environment.” International Organization 43:349-375. 18