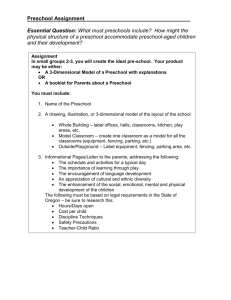

benefits of high quality early childhood education

advertisement