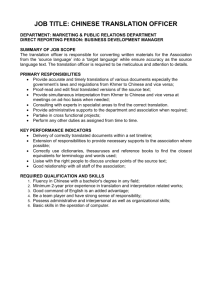

Translators in the Macartney Embassy to China, 1792-93

advertisement

China and Its Others: Knowledge Transfer and Representations of China and the West 28 – 29 June 2008 Chancellors Hotel & Conference Centre Manchester, UK Abstracts 1 Translating the Visual in Contemporary Chinese Poetry Dr Cosima BRUNO The School of Oriental and African Studies The University of London Abstract Partly because of the increased use of the computer in creative writing, from the mid-1990s onward, visual, audio and performing-arts components are being integrated into the Chinese poetic text in an unprecedented manner. This paper focuses on a number of poems where visual form interacts with literary technique. It is part of a bigger research project where I explore the possibilities offered by hypertext to translate contemporary Chinese poetry in its complexity of different semiotic components. I distinguish three different but not exclusive modes of resorting to the visual in contemporary Chinese poetry: exploitation of the pictographic function of Chinese characters to construct the poetic theme; typographical arrangement of characters to obtain an image which works in combination with the meaning of the verbal text; use of characters as visual components outside their meaning to achieve linguistic abstraction. When dealing with these kinds of texts, translators have often opted for a non-translation. Indeed, translation of these texts presents serious challenges: how can we translate facts and interpretations, sense and sensations between different artistic media and between cultures? Through an analysis of these texts and an investigation on the semiotic process activated by their visual form, I scrutinise how other translators have dealt with similar problems in the past and suggest possible renditions of these poems in English. My translation strategy is forged on the basis of the sensorial experience that affects the translator in front of these texts. On a general level, this is meant to harmonise translator’s psycho-perceptual response to the poem with various semiotic practices, which give credence to the phonic, the visual, and sophisticated hybrid devices, over the strictly linguistic. 2 Translating Kollontai and Transforming Chinese Women Prof Hsiang-yin CHEN Institute of Chinese Literature and Philosophy Academia Sinica Abstract In 1928, a male Communist, Sheng Duanxian, who is later known as Xia Yang, became the first Chinese translator of the writing of the most prominent Soviet Bolshevik feminist Aleksandra Kollontai. Interestingly, the male Communist translator chose the two stories ‘Liubov’ trekh pokolenii (The Loves of Three Generations)’ and ‘Sestry (Sisters)’ instead of any other of the female author’s political essays, reviews or critiques. The two stories were collected in the book named Lianai zhi lu (The Road of Love), primarily targeting the Chinese female educated readers. Such a translation strategy focusing on the factors as text type, audience and purpose evidently influenced the translation marketing at the end of the 1920s and the beginning of the 1930s; more and more Kollontai’s works, according to Russian original text or English and Japanese translation, were translated and introduced to Chinese literary circles. More importantly, the trend of translating Kollontai in the late 1920s and the 1930s was obliquely in the relation to a purpose of Chinese Communist policy of attracting more Chinese women to participate in the Party after Kuomintang’s purge of Communist in 1927. Deconstructing the wave of learning Kollontai’s emancipated female characters in the 1930s and 1940s, Kuomintang referred to Kollontai’s prominent narration of the sexual relationship to construct a political slogan ‘Yibeishui zhuyi (An ism of a cup of water)’ ridiculing “the complicated sexual relationship” between the Communists’ real lives in Yanan. Translating Kollontai therefore turned out to be not a simply business among translators, publishers and readers, but more like a struggle between the two opponent parties and the process of identifying and resisting. This article not only examines the evident influence of the Kollontai’s translation on the development of modern Chinese writing and sex politics, but also clarifies the misinterpretation, over-interpretation and misunderstanding between initiator, translators, communicators and receivers in Soviet Russia and China in the first half of the twentieth century. The first part of this article studies Kollontai’s discourse of constructing Communist morality, gender awareness and national identification, 3 portraying her blue print of sex politics under the Communist ideology. The second part shows the connection between the translation of Kollontai’s writing and female characters in Chinese texts. Furthermore, this part juxtaposes different versions based on Russian, English and Japanese, paralleling similarities, nuances and differences to investigate the phenomenon of misinterpretation, over-interpretation and misunderstanding, scrutinising and challenging the existent theories of translation studies. 4 Pseudotranslation, Gender, and Print: Two Examples from the Late Qing Prof Michael Gibbs HILL The University of South Carolina Abstract For nearly a century, scholars have lamented the many shortcomings of translators in the late Qing period: their lack foreign-language skills, unsystematic choice of source texts, their blasé attitudes toward documenting their sources and rendering quality translations, etc. In this paper, I look at how some of the most egregious examples of “bad” translation signal larger changes in authorial and intellectual labor at the turn of the twentieth century. I examine two texts that “fake” – or at least blur – their status as translation and the gender of their translators or authors: The Free Marriage (Ziyou jiehun 自由結婚, 1903), and “The Heroic Slave-Girl” (Xia nunü 俠奴女, published in Nüzi shijie 女子世界, 1904). Put together by at least one Chinese student in Japan, Free Marriage was an ambitious hoax: it featured a letter from its “author,” the translator’s postal address in Switzerland, an English-language title page, and a full set of commentaries to the text. Indeed, through its packaging, Free Marriage appears more authentic than many other late nineteenth-century translations that told readers nothing about the original author or source text. The second text, “The Heroic Slave-Girl,” was a “legitimate” translation of a story from a Japanese version of The Thousand and One Nights by Zhou Zuoren 周作人 and Ding Zuyin 丁祖蔭. In print, however, it was presented as the work of one “Ms. Pingyun” (Pingyun nvshi 萍雲女士). In my discussion, I ask: How do Free Marriage and “Slave-Girl” anticipate and play to readers’ expectations about translated fiction? In what ways do they mark themselves as an authentic foreign texts, and where do their acts of “passing” begin to unravel? At a time when many male literati published “women’s magazines,” what is the significance of this appropriation of the feminine in the literary labor of translation? By approaching these and other issues, this paper will provide new ways to understand the relation between gender and the role of translation in remaking the material practices of intellectual culture in fin-de-siecle China. 5 The War of Neologisms: The Competition between the Newly Translated Terms Invented by Yan Fu and by the Japanese in the Late Qing Prof Max K. W. HUANG Institute of Modern History Academia Sinica Abstract In the late Qing, many newly translated Chinese terms invented by the Japanese were imported into China with tremendous cultural effects. Facing this terminological invasion, Chinese officials, scholars, and students such as Zhang Zhidong, Yan Fu, Lin Shu, Zhang Binglin, and Peng Wenzu harshly criticized the new vocabulary. Moreover, some Chinese scholars, especially the famous translator Yan Fu, created new terms to replace the Japanese neologisms. This gave rise to a competition that lasted from the late Qing to the early Republican period. Yet by the 1920s, most of the terms with Japanese origins had been incorporated into the Chinese language at the expense of the terms created by Yan and other Chinese. This paper describes the competition and discusses the abandoned neologisms invented by Yan Fu. These terms included transliterated terms such as “tuodu” (拓都 total), “yaoni”(么匿 unit), “niefu” (涅伏 nerve), “luoji” (邏輯 logic), “wutoubang” (烏 託邦, utopia), as well as newly invented translations such as “guanpin” (官品 organic), “bule” (部勒 organization), “qunxue” (群學 sociology), “mingxue” (名學 logic), and “tianzhi” and “minzhi” (天直、民直 rights). Most of the terms invented by Yan fell before the Japanese neologisms. The failure of Yan’s own neologisms was also seen in his failure to unify translated terms when he was the head of the Office for the Compilation of Translated Terms in the Ministry of Education. The competition between the terms invented by Yan and by the Japanese indicates that Xun Zi’s view on “the correct use of names” is still insightful. Xun Zi noted, “Names have no intrinsic ‘appropriateness.’ They are bound to something by agreement in order to name it. The agreement becomes fixed, the custom is established, and it is called ‘appropriate.’…. Names do not have intrinsic good qualities. When a name is direct, easy, and not at odd with the thing, it is called a ‘good name.’” There were some “good names” in Yan’s translations, but unfortunately they were not fixed by the public agreement. Nevertheless, his ways of creating new terms revealed proper standards of translation. 6 The Translation of Ethics: the Case of Wang Guowei Prof Joyce C.H. LIU National Chiao-Tung University, Hsinchu Taiwan Abstract At the turn of the twentieth century, Chinese intellectuals were faced with rapid and frustrating changes of contemporary political situations as well as the vast import of European and Anglo-American thoughts. The task of translation became the vocation of most intellectuals of the time. Wang Guowei translated a significant amount of texts related to philosophical, psychological, educational and ethical questions especially during 1900 to 1911. The purpose of this paper is to examine Wang Guowei’s conceptualization of ethics in relation to the connection between the psyche and logos in his writings and his translations. The assumption of this project is to see Wang’s philosophical formulation of the concept of ethics not only as a translation and negotiation between Western thoughts, especially Kant, Schopenhauer and Schiller, and classical Chinese thoughts, but also as a revision of the concept of social-evolutionistic ethics, under the influence of Spenserian theories, that was prevailing at the turn of the century. 7 When the Big River Flows Toward the West: A Case Study of the English Translation of Li Qiao’s Wintry Night Kenneth Szu-han LIU University College London Abstract Dahe xiaoshuo (big river novel) is a unique genre in the development of Taiwanese literature. It has never played an important role in the mainstream literary production, yet eventually becomes a significant symbol and icon for Taiwan’s identity, due to the fact that it does not only construct the historical narratives in Taiwan, but also reflect the consistent resistance of people in this island against their environments, both natural and political. As an important genre to represent Taiwanese literature, dahe xiaoshuo are not absent in the English translation. However, when such novels are translated into another language, a few difficulties arise. First of all, since dahe xiaoshuo normally cover a long span of time, they tend to be voluminous and abridgement is therefore necessary. Secondly, dahe xiaoshuo is set to reflect a specific period in history and inevitably involve historical events and details in daily life at that time, which are not easily rendered into another culture. Moreover, the historical consciousness in dahe xiaoshuo is often the reflection of the authors’ criticism and interpretation to the history, which challenges translators’ interpretation of the source texts as well as the history. Last but not least, dahe xiaoshuo in Taiwan are generally heavily loaded with political ideology, because they are written in search of the roots with the historical mission to unveil what has happened in this island so that people living here will have a better understanding where they come from and where they should go. Such an ideology load always challenges the translators. In this paper, I will take Li Qiao’s Wintry Night, translated by Taotao Liu & John Balcom and published by Columbia University Press in the series of Modern Chinese Literature from Taiwan, as a case study to show how the translators tackled the above-mentioned problems. By close reading and comparison between the source text and the target text, I will pay special attention to the questions such as how a novel heavily loaded with cultural references and geopolitical ideology is rendered into another language and culture, how a three-volume work is abridged into one, what has been left out and how the abridgement affects the translation. I will argue that the English translation tones down the historical and ideological consciousness in the source text and hence re-presents Wintry Night not as a novel with the historical reality but simply a novel with the exotic historical flavour. 8 Translation of Hemingway’s The Old Man and the Sea in China (1956) Elaine Yin-ling NG University College London Abstract In the Communist era from 1949 to 1966 in China, foreign literature translation served the political functions of uniting the people to fight the enemy and to construct socialism. It was highly selective and biased towards the party. It soon became a mere tool of “proletarian politics,” a subservient instrument for ideological propaganda, and a collective enterprise that was organized and planned carefully under the leadership of Mao. This resulted in the general improvement in the quality of literary translation (Sun, 1996; Wang, 1995; Wong, 1999). The case study looks at the translation of Hemingway’s The Old Man and the Sea, produced by Hai Guan in 1956 during the early years of Communist China. It is the most popular work of Hemingway among all others which have been translated into Chinese. The novella and the short story “The Undefeated” were the only two works of Hemingway selected by the party to be translated both by Hai during that time. The image of Santiago as an undefeated hardened man has strengthened and enlightened thousands of Chinese people. The study explores the prominent characteristics of Hai’s translation in the rendering of diction, verbal and modal expressions, speech and thought presentation, and Europeanized structure – lengthy premodifiers. It also inquires into the causes of Hai’s linguistic choices by relating the textual features identified to the specific sociocultural and ideological contexts of production in an attempt to draw a causal link between them. 9 “Misogyny” and the Modern Girl: Scientific Jargon and Neosensation Prof Hsiao-yen PENG Institute of Chinese Literature and Philosophy Academia Sinica Abstract This paper analyzes the scientific jargon incorporated into Mu Shiying’s 1933 story “Bei dangzuo xiaoqianpin de nanzi” (A man taken as a plaything). Medical and psychological terms, such as “misogyny,” “autopsy,” “neurosis,” “indigestion,” “germ,” and so on, abound in the story. Typical of neosensationist stories, these terms, borrowed from Japanese translations of Western scientific lexicon, are used in a tongue-in-cheek fashion to ridicule a fickle modern girl who enjoys torturing her suitors. On the one hand, the story reflects the mentality and speech habits of college students in the metropolis who were well versed in the macaronic practice of language. One the other, the loose usage of scientific terms demonstrates how, since Hu Shi’s 1917 advocacy for vernacular literature as opposed to Classical literature, the vernacular awkwardly evolving in the 1930s resorts to vocabulary bantering with modern scientific knowledge. Most important, the scientific jargon used freely by characters in the story discloses how medical knowledge formulated people’s understanding of each other’s mind and body when disciplines such as psychology were to be established in China. 10 Text, Context, and Dual Contextualization— A Thick Translation of Gulliver’s Travels Prof Te-hsing SHAN Research Fellow and Deputy Director Institute of European and American Studies, Academia Sinica Adjunct Chair Professor, Providence University Abstract Gulliver’s Travels was first introduced into China by an anonymous translator/rewriter in 1872 and serialized in Shen Bao, one of the earliest daily newspapers in China, for only four days before coming to an abrupt end. Even since then, this text has been one of the most popular translations/mistranslations in the Chinese speaking world and has often been read as Children’s literature in a truncated version. It is not much of a stretch to say that it is the most misunderstood text in Chinese translation history. In 1997, the National Science Council in Taiwan launched the Project of Annotated Translation of Classics with an aim to introduce more classical texts and cultural capital, and to elevate the status of translation and translators. The goal being academic translation, the NSC established guidelines and invited scholars to submit their projects. In order to differentiate the products of these translation projects from others on the market, several apparatuses were required: a critical introduction, annotations, a chronology of the original author, and references. As a scholar-cum-translator for more than two decades, I have always been very concerned about the task of the translator and the important role that he or she plays. I firmly believe that in addition to translating the text proper, the translator, as a mediator between two cultures, should better serve his/her target audience by informing them about the reception history of a particular text, especially a classic, not only in its source cultural context, but also in its target cultural context. The annotated translation project of Gulliver’s Travels provides me with an excellent opportunity to carry out my theory of dual contextualization, which is derivative of my years of translation. This paper, therefore, is a self-reflection of a scholar-cum-translator whose thick translation of Gulliver’s Travels, under the sponsorship of the NSC, is expected to provide a unique Chinese translation of this literary classic for the first time since it was introduced to the Chinese-speaking world in 1872. 11 Exploring the role of pseudo-translation in the history of translation: Marryat’s Pacha of Many Tales Dr James ST. ANDRÉ The University of Manchester Abstract This paper sets out to demonstrate that pseudo-translation is an integral part of the history of translation, at least at certain times and places. Specifically, I demonstrate that for much of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, pseudo-translation was actually an important player in the contested field of translations from oriental languages and the emergent discipline of oriental studies. Such works were part of that field of knowledge, both at the specialist and the popular level, and helped shape contemporary European conceptions of the orient. Drawing on the work of Gideon Toury and Theo Hermans for theoretical justification, I use Bourdieu’s concept of the field of literary production to examine the interaction between genuine and pseudotranslations from Chinese into English from the eighteenth to the early twentieth centuries, focusing in particular on Sir John Francis Davis’s genuine translation, The Sorrows of Han, and Frederick Marryat’s pseudo-translation, The Pacha of Many Tales, which incorporates and orientalizes Davis’s translation. 12 Translation Practice Jarring with Theory: On Qunxue siyen (群學肆言,1903) Prof Daw-hwan WANG Institute of History and Philosophy Academia Sinica Abstract Yen Fu set up the theory of xin (fidelity), da (equivalence), ya (fluence) for translation criticism in the preface to his first translation work, Tienyen lun (Evolution and ethics). Popular among common readers for its comprehensiveness, it offers a convenient scheme and a common language for critics. Yet in practice Yen Fu didn’t follow his own theory, and he even warned that “those who should imitate my way of translation exhibited in this work would not benefit at all from me.” Thanks to scholars of Yen Fu, we have known a lot about the factors which contributed to this parodox. For example, Yen Fu’s own agenda of China’s survival in a world dominated by imperial powers played a central role in his selection of Western works to translate. However, a comprehensive study of Yen Fu’s practice as translator is still wanting: Tienyen lun has received too much critical attention, while Qunxue siyen (The Study of Sociology, by Herbert Spencer, 1873), too little. Considering the well-known fact that Yen Fu is a self-claimed disciple of Spencer, and that in Tienyen lun Yen Fu constantly cites Spencer’s arguments against Huxley’s, the lack of scholarly interest in Qunxue siyen raises intelletual curiosity. In this paper, I would show that the distortions of Spencer’s texts in Qunxue siyen were the result of lack of a common discourse between East and West. Yen Fu’s navy background at home and abroad was not enough for him to absorb the Spencerean discourse in its full panorama; his only recourse was the Classics, in which he had been immersed for years as a Chinese intellectual, and on which he framed his political agenda. It was unlikely that in his translation he could have followed his own theory. 13 Translators in the Macartney Embassy to China, 1792-93 Prof Lawrence Wang-chi WONG Nanyang Technological University Abstract In 1792, George Lord Macartney was sent by King George of Great Britain to visit Emperor Qianlong of the Qing Empire. While the visit was initiated under the pretext of congratulating the Emperor’s eighty-third Birthday, the real agenda was to press open the tightly closed door of the great Chinese Empire. Unfortunately, this first encounter of the two greatest powers on Earth was a complete failure. Macartney, after meeting the Emperor briefly for two times, left empty-handed, except some presents for King George and himself. Much has been reported and discussed on the Macartney Embassy. People try to identify the reasons of the failure from different angles. For a long time, the main-stream argument has blamed Emperor Qianlong for wrongly taking the British embassy as a traditional kind of tributary mission from inferior and uncivilized barbarians. Hence, he laid emphasis on such trivial matters as what presents were brought by the British and what rites were to be used to receive the embassy. His rejection of the requests of the British has been interpreted as an opportunity lost for China to get connected to the modern west. The purpose of the present paper is to look into a topic that has long been neglected: the translation activities that took place during the mission. While it is mere common sense that translation must play a crucial part in diplomatic exchanges between countries, there has not been any discussion at all on the topic in this first Sino-British encounter. However, the present paper demonstrates that translation played a vital part in the mission. By consulting first hand materials, we will first looking into the qualifications of the translators of both sides, followed by an analysis of their translations. Ultimately, we will determine how their performance seriously affected the outcome of the Embassy, in particular relation to the tributary issue. 14 Transference as Narcissistic or Traumatic: Contemporary Chinese Poets (Mis-)Translated from Their Western Predecessors Prof Xiaobin YANG Institute of Chinese Literature and Philosophy Academia Sinica Abstract Almost all major Chinese poets in the post-Mao era (including Duo Duo, Yang Lian, Hai Zi, Xi Chuan, Bai Hua, Chen Dongdong, Wang Jiaxin, Zhang Shuguang, Xi Du, Zhang Zao, Ouyang Jianghe, Sun Wenbo, Zang Di, Xiao Kaiyu, among others) have been enthusiastic in writing about their western (post-)modernist forerunners (Kafka, Baudelaire, Rimbaud, Yeats, Yesenin, Mayakovski, Mandelstam, Tsvetaeva, Gide, Breton, D’Annunzio, Brecht, Pound, Nabokov, Borges, Elytis, Brodsky, Ginsberg, etc.). In a way, this can be understood as translation of the great Western minds into the Chinese context. But if translation is etymologically synonymous to transference, we can discover that the process of translation can also be seen as that of transference in the psychoanalytic sense that links the Western masters (as texts) and their Chinese followers (as readers): the latter, nevertheless, transfer back feelings onto the former. My paper will, with the help of the Lacanian theory of transference, examine how various attempts of the Chinese poets address, in different ways, to the presumably authoritative Other, whom Lacan calls the “supposed subject of knowledge” (sujet supposé savoir). The two major trends of transference I will analyze in this paper will be: 1) identification with the Other as the ego-ideal to foster a narcissistic, albeit deceptive, urge for recognition that is expected to construct a new cultural subjectivity; and 2) transformation of the Other into an objet petit a as the way to invoke the ever-eluding desire and approach the traumatic core of the impossibility of identification or self-identity, a sensibility deeply embedded in the cultural symbolic in contemporary China. 15