This is Nylon - New Writing Partnership

advertisement

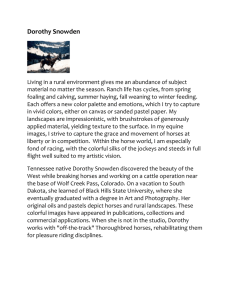

This is Nylon, a novel by Caroline Gilfillan The Mass-Observation Diary of Winifred Treasure, Widow with one son, a farmer from Dorset August 21st 1939 I have agreed to take part in the Mass-Observation exercise, having responded to an advertisement in the South Hatch Gazette. It will keep me occupied in the evenings. I love my Josh more than life itself, but a child’s company can become tedious. August 22nd 1939 Market day. Nothing to sell, but went anyway, and ended up buying a dozen chicks. August 23rd 1939 Listened to the news tonight. I fear that a war is approaching after all. Fields full of buttercups and daisies. Told Josh I had something in my eye when he asked why I was crying. August 30th 1939 Farmer from the next valley came to buy half a ton of hay. Helped him load it, glad of the extra money it has earned. Jersey just about to calf (at last – three tries before she fell). Josh over-excited about arrival of evacuated children. Wants us to have at least three. I’ve told him we can only have one – God willing, a boy that can help around the place. September 1st 1939 First night of blackout. Villagers complaining, though out here on the farm I’m used to the big, empty nights. Stuck brown paper over glass panels in back door in the afternoon. Rumour round the village that the evacuated children are to arrive today. Cleaned the spare room and made up a bed. Expected train bringing evacuees did not arrive. Josh awake half the night, asking if they were here yet. Caroline Gilfillan Extract from This is Nylon 1 September 2nd 1939 Kept Josh occupied by getting him to paint the tractor lights with tar. September 3rd 1939 War declared. The train of evacuated children finally turned up five and a half hours late. When I heard the news, I asked my cousin to look after a fidgety Josh, and drove into the village on the tractor. Arrived too late to find a good, strong boy: the best had been taken. Children that were left were a scruffy lot, in need of a bath. Billeting officer (a beanpole with a plum in her mouth) informed us we couldn’t refuse evacuees. Said it was against the law. I picked a quiet girl, who looked cleaner than most, fearing that I might be lumbered with a group of brothers and sisters. Her name is Dorothy. I THINGS CAN ONLY GET BETTER It all started (or finished) the day after the election, when Bernard sidled in the kitchen door like a skittish bullock, with a cock-eyed rosette drooping from his shirt. Dorothy stared at him, wrong-footed by the tilt of his head, the sheen of sweat on his broad forehead. ‘I suppose you’ve been celebrating,’ she said. ‘I thought you’d be back hours ago.’ He was breathing through his mouth, the huffs filling the cool white kitchen. ‘Well?’ She dried her hands on the tea-towel, concealing their tremor. Something was up: she could feel it her bones, her belly. He looked at her, blinking slowly, eyes dark as blackberries in the shade of the kitchen. As he started his speech she backed away, winded, silenced, until his words faltered and her voice rushed back up her throat, breathing flames, scorching his mumbles into ashen scraps. When she advanced towards him, Bernard hurried back up the hall and out of the house. At the front gate he turned and mouthed something she couldn’t hear, shook his head, the wiry hair glinting like iron filings in the sun, then set off downhill, breaking into an easy trot every few strides, until he turned left towards the town centre. Caroline Gilfillan Extract from This is Nylon 2 She stood, panting, while his words blossomed inside her like a scarlet ink blot dropped in water. Then she rang a taxi and went upstairs to pack, because she wasn’t having it: no sir. She wasn’t going to hang around to be humiliated. She was off. ‘Yes, I am,’ she whispered, clenching her fists. ‘Really I am.’ A few minutes later her head hung over the clothes folded at the bottom of the suitcase. ‘How could he?’ she whispered. Then she pulled herself upright and reached for the first of two bottles of gin (special offer) lined up on the bedside table. She wrapped each one in a cotton shirt before placing it carefully in the nest of slacks and skirts. ‘There, my little beauties. You’re coming with me. We’re taking a ride. We’re taking a trip to the big smoke. We’re on the road again.’ And here she hummed a few bars of the Canned Heat song, the airy falsetto of the melody looping through her head, bringing back the Sixties, the smell of patchouli joss sticks, that cheesy Afghan coat she’d bought in the hippy shop down by the prom that Bernard hated. Then her jaw clenched, smothering the last wavering notes of the tune. Oh, the sheer, bloody cheek of it! He was Mr Cardigan Man. Yes, he was. He was Mr Beige Cardigan with Leather Covered Buttons. She was the fizzy one. She was the one who should have done it to him. And I might have, she thought, squashing a wriggle of knickers and bras on to the wrapped bottles. I’ve had my offers; I’ve had my chances. What about that Maths inspector with a head like a moose? And the chemistry teacher – handsome widower from Pakistan with a scarred face. They could have cooked something up, but Dorothy had backed off. She wasn’t daft: she knew that one thing led to others. She slammed the suitcase shut, then sat on the lid and squirmed until she could fasten the catches. And, as she rested a moment, another figure slipped into her mind, and this one wasn’t square and solid, like Bernard, this one was leggy as cow parsley, and had the plant’s milky tinge and citric smell. Eyes closed, Dorothy moaned, feeling an ache in her ribs, her pelvis, that she thought had gone forever. Then she sprang off the suitcase, since she wasn’t a person to give into this sort of sweet ache. In fact she’d spent her whole life resisting it. Once you got the hang of it it was easy: you just did something else, and waited for it to shrivel up and blow away. Purposeful, she dropped to her knees. ‘Where are they?’ she muttered, fishing around in the fluff at the back of the wardrobe. If a new Dorothy was emerging, she needed some new shoes. ‘Ah, yes. Out you come, my little sweeties.’ Bring on the lime-green trainers Caroline Gilfillan Extract from This is Nylon 3 with the Velcro fastenings – the fuck-off trainers as Kelly, her grand-daughter, would put it. They’d been sat in their box in the back of the wardrobe for three months. She’d bought them on a whim, from a shop near the Pavilion, on a rainy afternoon when she was blue as buggery, then put them away unworn because they didn’t go with her tailored skirts and slacks. She slipped in her feet, fastened the Velcro. Standing up, she walked round the bedroom, thinking that these were tasty, comfortable, snug. Pretty damn fuck-off in fact. In front of the long mirror she pulled back her shoulders and lifted her chin: tight black teeshirt tucked into hipster jeans; a leather belt with a brass buckle; the sort of thing Kelly or Thea would wear. Leaning forward, she fiddled with the short spikes of her hair: cut and coloured last week, it was a cracker of a cut, with uneven wisps which could be left soft or sharpened into the gilt points of a battle helmet. The door-bell rang. Dorothy dragged the suitcase off the bed, bumped it down the stairs. The lime green trainers preceded her up the garden path, their luminous strips catching the sun. They led her towards the taxi, winking at her when a spoonful of tears rose in her throat. On the beach below the sea rolled shingle round its mouth, bringing to mind her two little girls charging down the pebbles to the sea, red and yellow ribbons flying from their bunches, and Bernard, stubby and strong, hurrying across the pebbles with four dripping cornets in his hands. She’d admired his red-blooded smell, his black hair and broad mouth. He’d been bullish, masculine. There had been so much of him at a time when there seemed to be so little of her. Come on, she breathed, as the driver heaved her suitcase into the boot. You can do it. You know you can do it. Don’t hang around. Leave first. ‘Station, please.’ Running, she picked up the train she wanted. At Victoria she dragged the suitcase on to the platform, reared it up on to its trotters, and headed for the platform exit. Before her in the taxi queue a clutch of suited women wafting booze and cigarette fumes hung from each others’ shoulders, bawling Things Can Only Get Better. Dorothy’s mouth curdled: or they could get worse; much worse. When her turn arrived she flopped onto the back seat of a taxi hung with air fresheners that smelt of fruit gums. As the elongated triangle of Islington Green whizzed past, she remembered sailing past it in the opposite direction on the 38, feeling sick as a drunken sailor. She’d worn a winter coat and a dress that was too tight round the middle because Thea, her younger daughter, was curled up in her belly. Thea: Dorothy’s mouth formed and held the shape of Caroline Gilfillan Extract from This is Nylon 4 the name. How well it suited her: cool, stylish, to the point. They’d have a chance to talk now – to really talk. It was about time. Thea’s notebook How did it happen? I’m going to write it all down, so that it’s clear in my mind, because I’m not sure how I got from A to B. From I to we. The day Mum turned up Kelly had dropped by on the way home from school. Though I’d got company (Christian) and this was the first time I’d asked him round, I didn’t mind, because Kelly’s a cool kid and I love her as much as I love anyone. We rolled a spliff. We drank some tea. We talked. She moaned about June, her hair lit marigold by the afternoon sun. I could almost taste the bluey hue of her neck, the gilt of the tiny freckles dusted on her nose. Could almost see the bones stretching to fill out her face. She was all mouth and limbs, flopped on the blow-up sofa. You’d better get back ‘cos June’ll be in from work soon, says I when the clock read half five, because I didn’t want her getting into trouble, and I didn’t want my sister charging round here like a buffalo. Kay, says she, a bit sad. As soon as she was out of the door, and SuperFly was on the turntable, Christian came over and grabbed me round the waist. You wicked woman, says he. Corrupting a young girl like that. Letting her smoke weed. I pointed out that she was fifteen, and could make up her own mind. He started nuzzling and nibbling the back of my neck, muttering he would have loved to have an auntie like me to introduce him to sex, drugs, and rock ‘n’ roll. I kissed him, to shut him up, and he was a good kisser, with a tongue that pushed rather than stirred. I like that. I manoeuvred him into the bedroom. The bed sang its familiar chord when we lay down. Then I started to unpeel his clothes like a banana skin. Lovely stuff underneath: milky upper-arms; a belly soft and sweet as white bread. I can’t stand the all-over tan. I like pale places, soft folds of skin. I like men when they’re naked and unprotected, and Christian was no exception. But, boy, was he in a hurry! Slow down, says I. Just lie there and take it for a bit. And he did. When it came to my turn, he delivered. And as he delivered I thought about the whole business. I mean, an orgasm’s an orgasm, isn’t it? Except it’s not. We all know Caroline Gilfillan Extract from This is Nylon 5 that. And doing it to myself doesn’t do the trick. Is that unusual? Most of my girlfriends say they can service themselves better than the average lover, but I need someone else’s skin on mine, someone else’s tongue in my mouth. If I do it myself I know exactly what’s going to happen. I prefer to have a real live person to participate in the process. The first side of SuperFly was finished before I asked Christian to stop. He scrambled up on to his hands and knees: in this four-square position, hair glistening in the sun, he looked like a golden labrador. I could almost see his tail wagging. Come on, then, says I, and he did and I liked the shape of him, the weight of him, stocky and substantial. That was far-out. It blew me away, says he, eventually, at the point where my mind was wandering and the record player arm clicked off the second side of Superfly. He nibbled my ear-lobe; I twitched my head away; I’m not keen on wet stuff round my neck. You’re so fucking sexy. Am I? says I, but in my mind I was scribbling a list of the things I had to do before I went to work that night at the club wash sheets hoover living-room plant nasturtium seeds redo nails (blue glitter) update record catalogue Yeah. You’re amazing. And then his mouth snail-trailed down my neck, in search of a breast. I slid out of the bed pronto. Some women can do it ten times over, but I’m not one of them. Anyway, I really did have things to do. I offered him a bath or a shower. He pouted: I wished he hadn’t. It made him look like a golden Labrador sulking because I wouldn’t throw the ball for him again. And, like a sulky puppy, he couldn’t let it go. Says he: I’m - er - around for a couple of weeks. Maybe we could get together again. Says I: Maybe. Says he: We could go out for a bite to eat. Says I: Maybe. Says he: Shall I give you a ring then? Says I: I expect we’ll bump into each other at the club. Says he: I don’t believe it: you’re giving me the brush-off. Says I: (but with a smile – believe me, this was not as cruel as it sounds): That’s right. Now get your arse in gear. For a second his face freeze-framed in disbelief, then he jumped up and dragged on his leather trousers, cursing as he caught some sandy frizz in his zip. That’s what you get for not wearing knickers, says I, but he wasn’t in the mood for post-sex banter. He wanted Caroline Gilfillan Extract from This is Nylon 6 to go into one, big-time. He wanted to tell me what was what, and as he did his vowels closed up till they were tight as his neat little public-school arse. There’s no need to get heavy. I mean, if you want me to leave, I’ll just fucking go. No way do I want to hang around. Gotta split in any case, ‘cos there’s a girl I’m meeting down Soho. A singer. Brilliant voice and sexy as fuck. My brother’s going to help her get signed, and… Oh, sod off! says I, when I could get a word in. Sling your hook. While he stuffed his feet into his industrial trainers, I examined my hair in the mirror: the roots had grown through about an inch – just as I liked them. Behind me, I heard him stamp around in the living room and scoop his belongings into his bag. ‘Bye, says I, as he slammed the front door. After he’d gone I pulled out a drawing pad and sketched the solid blocks of his torso and backside. Told myself I might work them up into something when I next went to my studio. Then it was time to get ready: I was working at the club that night, and I’m never late. Never. As I showered, I checked out my body: taut abdomen; small breasts; slim hips; a cloud of pale pubic hair. Silvery stretch marks shimmered like cobwebs under the skin. They no longer bugged me. They were a water mark of the fat kid I’d been before I managed to squeeze myself dry and start again. Then the phone went. It was her. Holy Shit. © Caroline Gilfillan Caroline Gilfillan Extract from This is Nylon 7