TK-503

advertisement

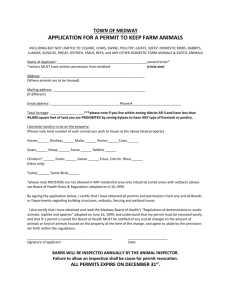

Indian Journal of Traditional Knowledge Vol. 6(3), July 2007, pp. 463-467 Use of indigenous plants for sustainable management of livestock diseases in rural Nigeria Ayoola Josephine B, R Ofukwu, Ama Teryila & GB Ayoola* Centre for Indigenous Knowledge in Farm and Infrastructure Management, Farm and Infrastructure Foundation, University of Agriculture, Private Mail Bag 2373, Makurdi, Nigeria Email: gbayoola@yahoo.com Received 24 March 2005; revised 19 March 2007 The paper examines local management of mixed infection of Newcastle diseases, coccidiosis and fowl typhoid in poultry birds, and Pestes Des Petits Ruminants (PPR) in sheep and goats in the middlebelt of Nigeria, wherein smallholder farmers either lose all their livestock or sell them off as the period when the diseases are most prevalent approaches. It discusses the technical and socioeconomic viability of the AKAGA and LOKA technologies that evolved from continued experimentation with local herbs within the agroecological zone. It concluded that the options are viable and sustainable within the context of the environment and socioeconomic circumstances of the people concerned. Key words: Livestock diseases, Nigeria, Indigenous plants, Medicinal plants IPC Int. Cl.8: A61D, A61K36/00, A61P1/00, A61P1/04, A61P1/10, A61P11/00, A61P11/10 Small holder livestock farming is an important traditional sector of Nigerian livestock industry comprising mainly of small ruminants and poultry, although in some parts including pigs. These animals play a vital role in the livelihood as they perform a lot of socio-economic roles besides contributing directly to family income and nutrition. They are insurance, a store of value and an important item at festivals and many cultural rites. Throughout Nigeria, families keep chickens and other classes of poultry under management systems that are based on maximizing output from minimal input hence showing family poultry as an economically efficient system, which yields low output, but from an even lower input1. This low output is evidenced in terms of low egg production, small sized eggs, slow growth and low survivability of chicks2. Family poultry at 104 million out numbers all other livestock in Nigeria, defining its socio-economic importance in livelihood improvement especially in the rural areas3. The farming populace of Ai-inamu community of Ogbadibo local Government in Benue state of Nigeria augments their cash crop earning with revenue from family livestock. It represents significant household savings, investment and insurance as well as —————— *Corresponding author contribution to family income and nutrition. Typical of Nigerian situation, high incidence of disease continue to be a major hindrance to livestock production in the study area4. The most common ruminant diseases in Ai-inamu community are scabies, PPR, and helminthiasis; and the most common poultry diseases include Newcastle disease (NCD), coccidiosis and fowl typhoid, which may occur as a mixed infection of the three thus creating an additional problem of diagnosing aside that of treatment5. The paper dwells on two technology options (AKAGA and LOKA), developed with farmers from their indigenous plants in a farmer participatory research. It considers their effectiveness relative to farmers’ alternative coping options, while also outlining the policy implications of such indigenous knowledge development and use. Methodology The study area of Ai-inamu community in Ogbadibo local Government area of Benue state, Nigeria is situated in the eastern part of Benue state within the middle belt zone of Nigeria. Data collection method included combined focused group discussion and focused group demonstration. AKAGA technology demonstration involved a total 464 INDIAN J TRADITIONAL KNOWLEDGE, VOL. 6, No. 3, JULY 2007 of 12 men and 30 women from about 40 households. It is prepared by a boiled mixture of one cup (ml) each of the leaves or bark of Annona senegalensis Pers., Khaya senegalensis A. Juss (locally called Achi-oyibo, for respiratory distress), and Anogessius leocarpus Roxb. (locally called otra- an antibacterial) with ¼ cup of ginger and one big bulb of alligator pepper in one gallon of water (Fig. 1). The mixture boiled for an hour and cooled is administered at a dose of 1ml/ bird every day for 5-7 days during disease out break and once every month particularly between the months of October to February for preventive measures. AKAGA is given to the birds as a treatment for NCD coccidiosis and fowl typhoid singularly and also as a treatment for their joint infection. Orthodox options however are specific for each disease type. The management of NCD involves vaccinating at 7 days, 3 weeks, 6 weeks and 18 weeks with NCDV, NCDV lasota, Komoro and NCDV komorov, respectively. Antistress vaccination is also administered on the birds. Treatment for coccidiosis may employ the use of anticoccidial drugs as preventive, control treatment regiments. Examples are sulphur drugs (sulphaquinoxaline, sulphamethazine, etc) Amprolium, Amprol plus, clopindoe, monensin that are given at various dosages in water for 7 days. The use of antibacterial drugs such as sulphamerazine, sulphaquaxaline and antibiotics such as tetracycline and chloramphenicol is also considered as treatment for fowl typhoid, which is given in water for 5-7 days. Orthodox options considered for the control of PPR in sheep and goats were erythromycin and streptomycin, while LOKA is the local alternative prepared from herbs. A ‘no treatment’ control experiment was also conducted. Again, a veterinary service provider supplied erythromycin and streptomycin, which were applied as prescribed. Materials for the LOKA option included one cup (ml) each of the leaves or bark of Anogessuis Leocarpus (otra-an antibacterial) Khaya senegalensis or lemon grass (achi-oyibo- for respiratory distress) and Ocinum spp (anyemba-for diarrhoea), with ¼ cup of potash (kanwa to stabilize the gastrointestinal system) in one gallon of water. The materials put in a pot are boiled for an hour and then allowed to cool. LOKA is prophylactic and so builds up strength in the animal so that they can withstand the stress of outbreak that usually occurs in the months of May and December. LOKA is given 20 ml twice daily for 7 days to young animals, while 40 ml twice daily for 7 days is given to sheep and goats in the months of April and November. Surveys using group discussions were conducted before and about 8 weeks after intervention. The sample comprised 80 farmers including 42 farmers who participated in the demonstration and 38 farmers, who did not but were later informed about the technology. Variables considered in the survey discussions included effectiveness of treatments, cost of materials for treatment and benefit from treatment among others. Effectiveness of technologies was measured by the number of goats, sheep and poultry birds that survived disease outbreak, cost of control in terms of cash and time and services rendered in orthodox treatment and benefits by the number and market value of the sheep, goats and poultry birds that survived. Generally, women and male youths are responsible for taking care of family livestock in terms of feeding and caring for the sick, irrespective of household category. The responsibility is more evenly shared in polygamous households where men also contribute in sheep and goats keeping, at an even ratio of 50% involvement of men, women and male youths (Table 1). The average poultry size is about 20 birds per household, mostly owned by women and youths. Similarly, men, women and youths usually own an average of 4 goats per household. Women and male youths are most critical targets for intervention on improved management of PPR infection in goats and sheep as well as mixed infection in poultry. Results and discussion All gender categories including men, women, and youths especially the poor have access to the AYOOLA et al.: MANAGEMENT OF LIVESTOCK DISEASES IN NIGERIA Table1— Gender and care of goats within households Gender category Women Men Male youths % Involvement by household category Monogamous Polygamous Female headed 100.00 100.00 50.00 50.00 50.00 50.00 100.00 materials for preparing the treatment except for Anogessius leocarpus, which does not grow within the community but is available in neighbouring communities. The possibility of propagating the herb for improving community access was explored, and its propagation by stem cutting was to be tried. All gender categories were involved in the technology development, while men and male youths may be involved in gathering the herbs, women and female youths usually prepare and administer treatment on poultry birds. Nigerian farmers very sensibly do respond to change provided firstly that it does not conflict with there time values and secondly that it pays6. Incidences of disease outbreak in the past have in most cases resulted in cent per cent losses in birds, if no treatment is given. Relative to an alternative of zero treatment, farmers consider the AKAGA a viable alternative. AKAGA is associated with a survival rate of 50-65%. It is quite effective but cheap especially when considered that it is treatment for a multiple of diseases in just a single dosage. It is also easily available, simple to prepare and non-toxic, having only the economic cost of the time spent in the collection of the materials for its preparation. Using the year 2000 factor prices, a household with an average of 20 poultry birds would require about N60.00 for modern treatment against mixed infection of fowl typhoid, Newcastle disease and coccidiosis in poultry birds to guarantee the survival of at least 10 or 12 out of 20 poultry birds. On the other hand, the materials for AKAGA are herbs, which are not necessarily purchased, except for the ginger and alligator pepper which are not grown in that area, estimated at about N1.00 / poultry bird. Very poor can afford N1.00 to treat a fowl and save N14.00 from avoiding the use of vaccine. The contribution of AKAGA spells a sustainability, which is consistent with the status of illiterate, and resource poor farmers of Ai-inamu community. Similarly, findings reveal that LOKA treatment was associated with a survival rate of 70%, about 465 20.5% lower than erythromycin but 10% higher than streptomycin treatment. Table 2 gives a benefit-cost analysis of LOKA versus orthodox options. Erythromycin requires about 15 naira per goat of cash expenses while LOKA requires just a naira for potash; implying about 1,400 % incremental monetary outlay for orthodox treatment. Therefore, a household with an average of 4 goats will require about 4 naira for treatment against PPR to guarantee the survival of at least 3 out of 4 goats. Hence, even the very poor can afford a naira to treat a goat by LOKA as opposed to the 15 naira required for administering erythromycin. However, the total cost of each option being the sum of the financial commitment on the treatment and the value of goats that did not survive. Erythromycin is least expensive while streptomycin is most expensive (Table 2). On the other hand, erythromycin is most beneficial, while streptomycin is least beneficial. The LOKA treatment emerges as being superior to the streptomycin option in terms of cost saving and incremental benefit as well as accessibility to farmers (Fig. 2). The implication is that if only streptomycin is available, a better option is LOKA with an incremental benefit of 10%. However Anogessius leocarpus, which is required for LOKA, does not grow within the community but is available in the neighboring communities within a range of 2-15 km. It is possible to encourage the propagation of the herb in the local communities for the purpose of increasing its accessibility (Fig. 3). The Table 2— Benefit cost analysis of alternative options for PPR in sheep and goats Treatment LOKA Erythromycin Streptomycin Control Survival rate (%) Benefits (N) Costs (N) 70.00% 90.50% 60.00% 40.00% 7000.00 9600.00 6000.00 4000.00 3004.00 460.00 4060.00 6000.00 Fig. 2—Benefit-cost analysis of alternative options for management of PPR in sheep and goats 466 INDIAN J TRADITIONAL KNOWLEDGE, VOL. 6, No. 3, JULY 2007 Fig. 3—Accessibility of herbs for managing mixed infection in old tree and PPR in sheep and goats policy aim of sustainable agriculture is environmental, social and psychological viability especially alongside the support of farmer-centered approaches7. AKAGA and LOKA emphasize the above statement pointing to the sustainability of such knowledge systems. For resource poor farmers, such credibility has to be in terms of cheapness, efficacy and general economic viability consistent with farmers’ economic status. The simplicity of the AKAGA and LOKA technologies in terms of preparation circumvents the problems associated with technologies developed based on high external inputs, which are most often not suitable to farmer’s socio-economic circumstances8. In most cases, farmers quickly become empowered in the required skill for such technologies as it developed from their own practices. The above attributes are all mutually reinforcing towards livelihood improvement and sustenance for the farmer. The relatively low cost implies that even the very poor can comfortably afford the technologies while their efficacy reduces the possibility of economic losses owing to disease attacks. Besides being indicative of livelihood improvement, these also will serve as entry points for such knowledge exploration. Since indigenous knowledge is constantly evolving, AKAGA and LOKA technologies leave room for more refinement while also stimulating thought to similar knowledge explorations9. The technologies are regarded as community owned, thus fostering their commitment to responsibilities towards further development. Such knowledge is regarded as an important source of accurate information and a corner stone of community development10. Therefore, indigenous communities will continue to regard it as a vital resource well worth preserving for the benefit of future generations. In Nigeria perhaps this approach will signify an important breakthrough in the poverty question where the absence of participatory policy formulation and implementation have always being the core of the matter11. A policy framework, which begins at the farmer’s knowledge and works upwards with a view to improving his livelihood, would be more sustainable especially because it takes into cognizance his socioeconomic and environment situation. This will create a bi-partisan institutional mechanism for empowering the population of farmers as active participants in the policy process as well as define their rightful roles in the development process11. There is also the obligation of encouraging the inextricable connections between man and his environment where nature is supported by nature in such a favourable policy environment. Acknowledgement Authors acknowledge the contribution of Mr P Ekuno in terms of support for fieldwork. References 1 Sonaiya EB, Backyard Poultry Production for Socioeconomic Advancement of the Nigerian Family: Requirements for Research and Development, In: Proc Int Seminar Promoting Sustainable Small-scale Livestock Production Towards Reduction of Malnutrition and Poverty in Rural and Sub-urban Families in Nigeria, (1999, 24-41. 2 Smith AJ, Poultry, (CTA Macmillan Publishers, London), 1990. 3 Federal Department of Livestock and Pest Control Services, Nigerian Livestock resources, Vol1, Executive summary and atlas, (Federal Department of Livestock and Pest Control Services, Abuja), 1992, 30. 4 Shawulu CJ, Common Animal Health Problems in Smallholder Livestock Farms: Experiences and Challenges for the Control of Livestock Diseases, In: Proc Int Seminar on Promoting Sustainable Small-scale Livestock Production Towards Reduction of Malnutrition and Poverty in Rural and Sub-urban Families in Nigeria, 1999, 164-174. 5 Anonymous, An assessment of Alternative Technologies for Managing Mixed Infection of Newcastle Disease, AYOOLA et al.: MANAGEMENT OF LIVESTOCK DISEASES IN NIGERIA Coccidiosis and Fowl Typhoid in Ogbadibo Local Government Area of Benue State, Nigeria, 2000, 12. 6 William SK, Taiwo Rural Development in Nigeria, (University of Ife Press, Ile-Ife, Nigeria), 1978. 7 Wibberely J, Promoting sustainable livelihoods through farmer groups and farm household’s development initiatives, In: Proc Int Seminar on Promoting Sustainable Small-scale Livestock Production Towards Reduction of Malnutrition and Poverty in Rural and Sub-urban Families in Nigeria, 1999, 104-139. 8 Ayoola JB & E Okoroafor, Socio-economic Considerations for Sustainable Uptake of Neem Technology for Pest Control 467 in Benue State, Nigeria, Int J Agric Biol Sci, 3(8) (2004) 4958. 9 Ortiz O, Understanding Interactions between Idigenous Knowledge and Scientific Information, Indigenous Knowledge Dev Monitor, 7(3) (1999) 7-10. 10 Henry P, Huntington & Maria E Fernadez-Gimenez, Indigenous Knowledge in the Artic: A review of Research and Applications, Indigenous Knowledge Dev Monitor, 7(3) (1999) 11-14. 11 Ayoola, GB, Farm and Infrastructure Foundation: Mission and Mandate, (Founders Press, Makurdi, Benue State, Nigeria), 1999.