introductory session - Are you looking for one of those websites

advertisement

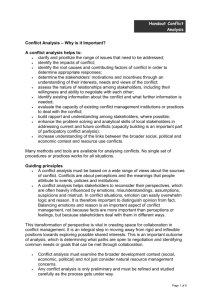

INTRODUCTORY SESSION. This Course Element constitutes a general introduction to the theory of Conflict Management. Change almost always brings about conflicts between the needs and wishes of different stakeholder groups. Conflict prevention by consensus building and when applicable conflict resolution, are needed to win the support of a maximum of stakeholders. Conflict Management offers approaches that help in preventing or resolving conflicts. It is important to note that conflict management has a cultural dimension as different cultures will have different ways of perceiving, acknowledging and approaching a conflict. In short, conflict management recognises that conflicts are a normal part of life but that well managed they can be an important force for positive change allowing people to fully express their views in a peaceful setting and to learn about each others perception of the same questions. A facilitator may be required to match these different perceptions and to express the perception of the conflict per group of stakeholders. Stakeholder analysis (e.g. Stakeholder Conflict and Partnership Matrix, Social Mapping) is therefore an important part of the process. Power issues appear when specific groups (e.g. women) have a less access to resources or to decision making. Sometimes this may even be embodied in the policies or legislation of the country. THE CIRCLE OF CONFLICT One approach in conflict identification is known as the circle of conflict. Positioning the problem in the circle helps analysing causes and finding solutions. Five categories of conflicts are recognised as described hereunder. Data Conflicts are caused by lack of information, spreading of misinformation, different views on what are relevant data, different interpretations of available data, or different assessment procedures. The point is to reach an agreement on what data are important, to agree on data collection procedures, to develop common criteria for data assessment by for example relying on third party experts to gain outside opinion or break through bottlenecks and deadlocks. Needs and Interest Conflicts are due to perceived or actual competition between substantive (e.g. the land), procedural (e.g. incentives, fees or charges) or psychological (e.g. environmental awareness) interests. Possible solutions are reached by focusing on interests instead of on the positions, looking for objective criteria, developing integrative solutions addressing the needs of all parties, searching for ways of expanding options or resources, and by developing trade-offs satisfying interests of different strength. Structural Conflicts proceed from geographic, physical or environmental factors as well as time constraints that hinder co-operation. The lack of appropriate procedures and legislation is here often to blame. But also, from the general set up and role distribution of a situation, from unequal power and authority in the decision-making process, form negative patterns of behaviour and interaction, or from the unequal control, ownership or distribution of resources. Possible solutions comprise the clear definition and acceptance of roles and levels of authority when needed with external mediation or arbitrage, the reallocation of rights and entitlements, the relocation of the negotiation platform at a convenient distance from the field, the establishment of a fair, HEPPAP – Course 1. Organisations, Collaboration and Conflict Management Page 1 transparent and acceptable decision-making process. This involves the replacement of negative behaviour and positional attitudes by interest-based persuasive trade-off bargaining negotiation in an appropriate timeframe. Cultural differences bring about Value Conflicts of various kinds. Next to the economical value of nature, goods and services, there is the difficulty to define criteria for evaluating ideas or behaviour, the variability in ways of life or perception of what is important in frame of the prevailing local ideological or religious context. Values are in fact part of the indigenous knowledge and at the basis of people choices and priorities. Direct attempts to change the values of a group do usually face strong opposition. Challenging values is thus not the appropriate approach but issues should be redefined in other terms than cultural values. Parties should agree to disagree on their own values while looking for a common (“superordinate”) goal they all can share. The most useless conflicts probably are those grouped under the name Relationship Conflicts. These involve strong disagreement between deciders on the basis of strong emotions or dislikes, misperceptions or stereotypes, poor communication leading to an accumulation of wrong assumptions, and repetitive negative behaviour. Therefore, appropriate communication channels should be installed, people should learn to control their expression and build positive perception skills in order to develop a positive problem-solving attitude. People with a negative attitude should whenever possible be removed from their position or made harmless. The distinction between unnecessary and genuine conflicts is quite artificial. The circle of conflict can be used in a participatory manner with all stakeholders. It should be noted that there is a possible overlap between categories and that a given conflict does not necessarily perfectly fit into one category. Different tools can be used in support of the approach. For example, listing Resources, Constraints, Risks and Investments per stakeholder (Resource and Constraints Analysis) or performing a SWOT Analysis (Strengths, Weaknesses, Opportunities and Trends) per activity. To make full use of the population’s indigenous knowledge of traditional land use practices based on limited use of external inputs value restoration and consensus building will be the first priority. Good communication and information exchange is here vital. In order to discuss and test possible new conservatory practices, Participatory Technology Development (PTD) could be tried. For the evaluation of the application of new solutions, an integrated approach involving participatory alternative building and comparison is recommended. INTEREST-BASED BARGAINING Stakeholders will want to confront their interests in satisfying their needs. They bargain for a better possibility to achieve their goals. Most often they will express their interests in terms of a single solution (their position) to the problem. In Interest-based Bargaining it is important that all interests be addressed and that stakeholders be stimulated to come up with their views. The facilitator should aim at understanding the emotional dynamics beyond the statements of interests, identifying the values and interest that underlie positions and separating them so as to defuse value conflicts, bringing parties to review the history of the conflict in a neutral setting under a new “positive” light. Through common brainstorming, options and alternatives can be HEPPAP – Course 1. Organisations, Collaboration and Conflict Management Page 2 listed regardless of their practical feasibility, and assessment criteria can be discussed that will be agreed upon to evaluate solutions. Starting with higher level general requirements makes a general agreement more likely. The further detailing should justify the legitimacy of the needs of the various groups. The conflict will only be satisfactorily resolved if none of the groups of interests is left out of the process. Moreover, it is vital to avoid focusing on positions, as this could block the process. Instead, creative solutions can be found when the focus is on identifying and satisfying legitimate needs and interests. THE CONTINUUM OF CONFLICT MANAGEMENT AND RESOLUTION APPROACHES Various representations of the Continuum of Conflict Management can be found in literature. One example is given below. From left to right there is a general increase of coercion and likelihood of reaching a win-lose situation. The decision-making is private by the parties or with help of a third party, authoritative under control of a third party often with legal enforcement powers, extralegal when the decision is forced by direct or violent action. Avoidance Discussion Negotiation Private, by the parties themselves, or Mediation Administrative Decision Arbitration third party Authoritative, by third party Judicial Decision Legislative Decision Legal authoritative Direct Action Violent Action Extralegal coercive More information on conflict management theory can be found in Annex 1, which is extracted and adapted from a report presented to ESCAP in Bangkok in 1998. GLOSSARY Access to resources. A series of participatory exercises that allows development practitioners to collect information and raises awareness among beneficiaries about the ways in which access to resources varies according to gender and other important social variables. This user-friendly tool draws on the everyday experience of participants and is useful to men, women, trainers, project staff, and field-workers. Advisory non-binding assistance. This type of assistance, often arbitration or expert panels, shifts the bulk of the authority over the conflict, i.e. determining a solution and recommending what is “fair”, to the outside experts. The communication pattern is between the arbiter/panel and the parties. Parties retain the power to accept or reject the recommendations. Alternative Dispute Resolution (ADR) refers to a variety of collaborative approaches that seek to reach a mutually acceptable resolution of issues in a conflict through a voluntary process. Such approaches were developed as alternatives to adversarial or non-consensual strategies, such as judicial or legal recourse, unilaterally initiated public information campaigns, or partisan political action. All of these latter strategies might also be appropriate and legitimate means of addressing disputes, depending upon the context. Alternative conflict resolution approaches complement these more adversarial strategies, and broaden the range of tools available to communities and interest groups who are involved in conflict (FAO, 1994). HEPPAP – Course 1. Organisations, Collaboration and Conflict Management Page 3 Arbitration: "a process that involves the submission of a dispute to an arbitrator (anyone mutually agreeable to the parties), who renders a (binding or advisory) decision after hearing arguments and reviewing evidence." (NIDR no date) Binding Assistance. Binding assistance, through arbitrage or judging, passes authority over the conflict completely over to the outside party. Collaborative Planning: "a process in which parties agree to work together in anticipation of a conflict, and work collaboratively to plan and manage ways to avoid the conflict." (NIDR no date) Conciliation: "an attempt by a neutral third party to communicate separately with disputing parties, for the purpose of reducing tensions and agreeing on a process for resolving a dispute" (Pendzich et al. 1994:8-9). Conflict Anticipation: "the identification of disputes at their early stages of development, targeting and educating potential interest groups, and attempting to develop cooperative responses to the future problem, thus avoiding or lowering the destructive effects of conflict." (CDR Associates 1986:3) Conflict Management is a multidisciplinary field of research and action that seeks to address the question of how people can make better decisions collaboratively. It is an approach that attempts to address the roots of conflicts by building upon shared interests and finding points of agreement that accommodate the respective needs of the various parties involved (Anderson et al, 1996). Consensus Building or conflict prevention: a process leading to "an agreement (or synthesis) that is reached by identifying the interests of all concerned parties and then building an integrative solution." (CDR Associates 1986:3). This group of approaches, often linked to participatory planning methods or stakeholder participation, focuses less on the resolution of a specific conflict than on fostering a cooperative (planning) process for complex, multi-issue, multi-user situations. Focus group meetings. Relatively low-cost, semi-structured, small group (four to twelve participants plus a facilitator) consultations used to explore peoples' attitudes, feelings, or preferences, and to build consensus. Focus group work is a compromise between participant observation, which is less controlled, lengthier, and more in-depth, and preset interviews, which are not likely to attend to participants' own concerns. Mapping. A generic term for gathering in pictorial form baseline data on a variety of indicators. This is an excellent starting point for participatory work because it gets people involved in creating a visual output that can be used immediately to bridge verbal communication gaps and to generate lively discussion. Maps are useful as verification of secondary source information, as training and awareness raising tools, for comparison, and for monitoring of change. Common types of maps include health maps, institutional maps (Venn diagrams), and resource maps. Mediation: "the use of a neutral third-party in a negotiation process, where a mediator assists HEPPAP – Course 1. Organisations, Collaboration and Conflict Management Page 4 those in a conflict situation in reaching their own agreement, but has no power to direct the parties or attempt to resolve the dispute" (Pendzich et al. 1994:8-9). Needs assessment. A tool that draws out information about people's varied needs, raises participants' awareness of related issues, and provides a framework for prioritizing needs. This sort of tool is an integral part of gender analysis to develop an understanding of the particular needs of both men and women and to do comparative analysis. Negotiation: "a voluntary process in which parties meet face to face to reach a mutually acceptable resolution of a conflict" (Pendzich et al. 1994:8-9). Non-Binding Arbitration. Non-Binding arbitrage is finding out what a neutral third party or a fair, impartial person or panel would think of the dispute. The opinion is advisory but normally carries a great deal of weight if the parties have confidence in the arbitrator. Participation; Development practitioners use a wide variety of different methods, tailored to different tasks and situations, in support of participatory development. Bellow ten methods are introduced that have been used in different development situations to achieve various objectives. These include: workshop-based and community-based methods for collaborative decision making, methods for stakeholder consultation, and methods for incorporating participation and social analysis into project design. Further on, each method is compared and contrasted with the others and their advantages and disadvantages noted to help Task Managers choose those most useful to them. A glossary of available tools, many of which are components of the methods, follows the summaries. More details on both the methods and the tools can be found in the Participation Sourcebook (World Bank, 1996). Participant observation is a fieldwork technique used by anthropologists and sociologists to collect qualitative and quantitative data that leads to an in-depth understanding of peoples' practices, motivations, and attitudes. Participant observation entails investigating the project background, studying the general characteristics of a beneficiary population, and living for an extended period among beneficiaries, during which interviews, observations, and analyses are recorded and discussed. Preference ranking. Also called direct matrix ranking, an exercise during which people identify what they do and do not value about a class of objects (for example, tree species or cooking fuel types). Ranking allows participants to understand the reasons for local preferences and to see how values differ among local groups. Understanding preferences is critical for choosing appropriate and effective interventions. Partnering. Based on the principle that traditional adversarial relationships can better be replaced through team-building activities by a co-operative approach preventing disputes. The approach requires personal relationships and commitment, common goals and dispute prevention processes. It supposes improved communication and on-time performance. Procedural assistance. Facilitators or mediators may also provide procedural assistance to the communication process among the parties in conflict, ranging from joint brainstorming sessions HEPPAP – Course 1. Organisations, Collaboration and Conflict Management Page 5 to parlaying information back and forth. When providing procedural assistance the facilitators explicitly do not involve themselves in the substantive issues, however, and do not suggest solutions or negotiating positions. The responsibility both for designing solutions and for finding agreement remains with the parties in conflict. Relationship building. A relatively “light” form of intervention is when outside facilitators arrange some activities to (re-) build a working relationship among the parties, in cases of conflict where this does not exist or has deteriorated during the conflict. This leaves the responsibility for the conflict resolution process to the parties themselves, i.e. identification of and negotiation over solutions. Role playing. Enables people to creatively remove themselves from their usual roles and perspectives to allow them to understand choices and decisions made by other people with other responsibilities. Ranging from a simple story with only a few characters to an elaborate street theatre production, this tool can be used to acclimatise a research team to a project setting, train trainers, and encourage community discussions about a particular development intervention. Stakeholders are people who may –directly or indirectly, positively or negatively – affect or be affected by the outcome of projects or programmes. This means that stakeholders are likely to outnumber project users. (p. 5/15, section I, IDB, 1997a). Substantive assistance. Mediators can also involve themselves in the fashioning of the solutions, i.e. provide substantive assistance as well. In this case the parties share with, or turn over to, the mediator the responsibility for identification of the solutions, but maintain direct communication and retain the authority to determine what constitutes an agreement. Surveys. A sequence of focused, predetermined questions in a fixed order, often with predetermined, limited options for responses. Surveys can add value when they are used to identify development problems or objectives, narrow the focus or clarify the objectives of a project or policy, plan strategies for implementation, and monitor or evaluate participation. Among the survey instruments used in Bank work are firm surveys, sentinel community surveillance, contingent valuation, and priority surveys. Village meetings. Multiple use meetings in participatory development, including information sharing and group consultation, consensus building, prioritisation and sequencing of interventions, and collaborative monitoring and evaluation. When multiple tools such as resource mapping, ranking, and focus groups have been used, village meetings are important venues for launching activities, evaluating progress, and gaining feedback on analysis. Workshops. Structured group meetings at which a variety of key stakeholder groups, whose activities or influence affect a development issue or project, share knowledge and work toward a common vision. With the help of a workshop facilitator, participants undertake a series of activities designed to help them progress toward the development objective (consensus building, information sharing, prioritisation of objectives, team building, and so on). In project as well as policy work, from preplanning to evaluation stages, stakeholder workshops are used to initiate, establish, and sustain collaboration. HEPPAP – Course 1. Organisations, Collaboration and Conflict Management Page 6 HEPPAP – Course 1. Organisations, Collaboration and Conflict Management Page 7 ANNEX 1. EXCERPTS FROM AN ESCAP REPORT ON CONFLICT MANAGEMENT EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 1. Introduction Wetland management and conflicts Conflict management can be called the greatest challenge of Integrated Wetland Management. Almost any significant development of the wetland zone, be it for tourism, biodiversity, fisheries or residences, is likely to infringe on the rights or expectations of others and, hence, to lead to user conflicts. In practice, it can be observed that projects and papers most often tend to describe the conflicts among users – and call for an integrated approach – but do not address the conflicts directly. Wetland managers usually are not trained – and do not posses the tools – to manage conflicts. Often also, environmental issues (for example, pollution) and resource user conflicts (for example, fishing conflicts) are not clearly distinguished from each other, perhaps because of the frequent cause-effect relation existing between the two. In this report is argued that conflict management, starting with the careful identification and analysis of potential conflicts at the early stages of project preparation, should become an explicit component of integrated wetland management. Therefore, conflict management techniques should become part of the toolkit of wetland managers. Wetland Conflicts This report examines the potential of methods and techniques that explicitly address “conflicts”, jointly referred to here as conflict management, to contribute to wetland management. Wetland conflicts are defined as situations or circumstances where strong and persistent divergence of positions (needs, values, etc.) among wetland users and other stakeholders represent an obstacle to efficiently managing a defined wetland area. Conflict management is a well-developed field of social sciences but has not been applied much to the management of natural resources in general and to the management of wetland zones in particular. It is recognised here that all societies develop institutions to deal with conflicts. When change in society is rapid, however, institutions are likely to lag behind. This situation is currently found in many wetland zones. In the long-term, the formal institutions may increase their capability to deal with wetland conflicts, but in the short-term explicit conflict management approaches will have to be built into wetland management projects and programmes. Conflicts in Asia and the Pacific Attitudes towards conflict influence the behavioural choices that people make when confronted with disputes. A key part of using conflict management techniques in Asia and the Pacific therefore involves understanding attitudes towards conflict throughout the region. Of fundamental importance is the concept of authority in terms of the structure of power. In some of the countries in the region a powerful political elite or ruling family was until recently or still is in control of the decision making. This party could enforce a solution –commonly described as the Best Alternative To a Negotiated Agreement (BATNA)- and thus had no incentives to participate in a conflict management process. This recent history still influences the attitudes of stakeholders in the region. Regional cultural aspects do affect the discussion of conflict management as well. Examples of aspects, which may be perceived very differently throughout the region, are: Emotional contents of sovereignty over jurisdictional waters Attitude of dependence on government intervention High respect of hierarchy or seniority HEPPAP – Course 1. Organisations, Collaboration and Conflict Management Page 8 Strong traditional decision making structures Community shared resources as part of the cultural background Strong customary land and marine tenure system Avoidance of face to face confrontation Tradition of political violence Political cost of decision making in front of the electorate Tendency to intermingle business and personal issues Urge to use discussion to maintain social networks 2. Conceptual Framework Conflict Management & Participation The high priority accorded to “ownership of projects” and “stakeholder participation in all programme phases” is a typical success factor for all integrated resource and environmental management fields. Stakeholders, as defined in the IDB Resource Book on Participation, are “people who may –directly or indirectly, positively or negatively – affect or be affected by the outcome of projects or programs. This means that stakeholders are likely to outnumber project users”. Conflict management is closely linked to participation of stakeholders. The most significant influence on the prevention and resolution of conflicts in wetland management is likely to result from early participation. Thus, effort should be made not to limit participation to consultation procedures after experts have already designed the project alternatives or management interventions. This study explicitly focuses on the prevention, occurrence and management of conflicts. In this context stakeholder participation is recognised as an important response to a conflict situation. However, it is not the only possible action. Furthermore, depending on the characteristics of the conflict, other approaches may be identified as more suitable. Conflict management & Wetland Management Wetland managers come from diverse fields, but mostly have a natural science or engineering background. Conflict management, on the other hand, started as a subject of social and behavioural sciences with the focus on alternatives to legal procedures. Traditionally, limited overlap exists between both groups. The following benefits of conflict management, both as part of project preparation and as a component in project execution, are identified: 1. Ownership of the project 2. Contribution to resolving pre-existing conflicts among stakeholders 3. Prevention of delays during execution as well as sub-optimal project performance 4. Reduction of costs of conflicts later in time Conflict management techniques Six main groups of conflict management techniques are distinguished, ranging from methods that leave the responsibility for the identification and negotiation of solutions to the conflict with the parties themselves, to methods that put this responsibility in the hands of third parties: 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. Consensus building or conflict prevention Relationship building Procedural assistance Substantive assistance Advisory non-binding assistance 6. Binding Assistance HEPPAP – Course 1. Organisations, Collaboration and Conflict Management Page 9 Conflict Assessment A crucial first step in any conflict management approach is conflict assessment. Four main factors have been distinguished, that need to be analysed in determining the scope, nature and stage of a wetland management conflict: 1 2 3 Characterisation of conflict and stakeholders. Stage in the project cycle. Stage in the conflict process. 4 The legal and institutional context. The overall conclusions of the study are: Cultural diversity Asian and Pacific countries do not constitute a homogeneous group. Cultural and societal differences are very important in the region and it is unlikely that a single approach will equally suit all countries. The inclination shown by various agencies and international organisations to organise their work on the basis of great blocks of countries may find its justification in Africa or Latin-America but obviously is inappropriate to the Asian and Pacific region. Here, subdivisions should be considered to reflect the cultural diversity of the region. Moreover, ethnic variations including groups that are culturally extremely different can occur in wetland zone or small island areas. Sociologists or anthropologists recognise various types of informal groups of people: ethnic groups, kin groups or territorial groups, for example. The existence of these should be taken into account. Political diversity Also in terms of political systems, Asian and Pacific countries do show a wider diversity than other regions in the world. Hence, the concepts of stakeholder, participation or conflict management will have a different content and context, and therefore the approach to consensus building will have to be adapted to fit in the local system. Subdivisions should be considered to reflect the political diversity of the region. Bureaucracy Many countries have a fairly complex system of authority and a plethora of competent agencies usually inherited from past colonial history. Overlapping attributions do create conflicts of competence, intricate procedures and confusion in the final decision. Cultural aspects may lead officials to use knowledge as a means to gain power so that the circulation of information is minimal. The simplification of structures and procedures is a must to ensure transparency. The access to information is a condition to effective participation. Therefore, involving the grassroots level in collecting and processing information in its own language is one of the key to successful participation. Language diversity Major ethnic variations including groups that are linguistically different can occur that will impair communication between communities in the wetland zone or small island areas. On a regional level, the language diversity and lack of a common language do not facilitate the dissemination of information between countries and even within countries. Wetland zone boundaries In most countries, the definition of the administrative boundaries of the wetland zone is still inappropriate. Boundaries based on an arbitrary distance measured from a tide level line do often result in splitting up morphological or ecological units such as lagoons or wetlands. This is causing either an overlap in competence or voids in regulations. HEPPAP – Course 1. Organisations, Collaboration and Conflict Management Page 10 Top-down planning structures Being the least empowered, politically, economically, socially and academically, local communities often are unable to express their needs and to be heard from the decision-makers. The result of this alienation from the planning process is a certain discontent with ill-adapted measures for which the level of acceptance will be low. The hiatus between decision makers and planners who dispose of all relevant tools at the higher level, and local communities who are unequipped at the lower level, makes that the target group of the planning is considered the least capable of being a partner in the planning. Most often a top-down approach is adopted, instead of a bottom-up process, while the beneficiary groups best know what they need and how to fulfil this. Drastic measures such as resettlements are often taken without sufficient explanation work. Voluntary conservation measures are only likely to succeed in frame of a structure of empowerment and co-management. However, the sole bottom-up approach should also not be regarded as the ultimate solution. Tradition and social pressure Traditional communities sometimes have very ancient ways of life, which are not likely to change if communities do not have the opportunity to ensure their survival through tapping alternative sources of livelihood. Environmentally damageable practices such as coral mining or illegal fishing will thus only be abandoned if they become socially unacceptable to the community themselves. Voluntary conservation measures are therefore more likely to gain acceptance in community-based programmes providing a co-management structure of empowerment and law enforcement. However, poverty alleviation measures must be taken at the same time to offer alternative sources of livelihood. Involvement of outsiders In the conflicts involving an international donor agency there is a risk for an expert-dominated approach. Donors do not always consult stakeholders effectively. Either the timing of the consultation or the composition of the consulted groups can be less than optimal. It is observed that donors or international agencies do have their preferred counterpart organisations at country level and that they thus are not quite able to integrate as they have a tendency to adopt a traditional way of funding sector activities. Participation as a means, not an objective There is a trend in some countries to include participation more as an objective in itself, than as a means to an end. The composition of the groups of stakeholders and the methodology chosen may then not take into account all stakeholders involved. Issues and problems may be overlooked because too much importance is given to the tool. A responsible use of participatory techniques should be encouraged. Importance of timing and preparation of participation Participatory approaches can be made more efficient, when started early in the design phase. This is clearly perceived in various countries. However, donor pressure to complete proposals and plans may cause late or insufficient participation. In addition, all stakeholders should be involved and appropriate information should be provided about the issues at stake. Furthermore, the design of the process should be clear to all stakeholders. Choice of a method and mediator The choice of a suitable conflict management technique and mediator is extremely important, as is the need to adapt to local conditions, culture and society. Several sections in this report are dedicated to this topic. HEPPAP – Course 1. Organisations, Collaboration and Conflict Management Page 11 Expert bias Davos et al. (1997) conclude that wetland management projects in general are expert-driven and outcomeoriented. A recent review of World Bank Practice (World Bank, 1997) concluded that multilateral organisations also tend to have a bias towards solutions to problems or conflicts based on expert opinion. The standard solution to a problem is to have an expert staff member, or a consultant recruited for the purpose, study the issue and propose a solution. Issues are often defined as “technical” problems, related to water quality, poverty or public health, for example, and solutions are defined in terms of “fundable” – often though not always physical – interventions. Given that one of the main products in support of “lending” of the development banks has always been “technical assistance”, this is very understandable. Consultants and agencies can and do consult with stakeholders, but the terms of reference of their assignments usually put high expectations on rapid identification of well-defined solutions. In the review referred to above, it was concluded that in most cases World Bank staff and external (international) experts define the terms of reference (ToR) for the consultative process. The nature of the consultations following the ToR and results then “tends to be to convince affected people and other stakeholders of the validity and wisdom of the choices already made.” (World Bank, 1997, p. 36) 5. Suggestions for further action Capacity Building Wetland managers as well as agencies are insufficiently aware of the importance of conflicts in wetland management and of the methods and techniques available to manage them. In addition, local communities are often not at a point where they can negotiate with powerful stakeholders. Therefore, capacity building for conflict management needs to reach agencies, wetland managers in the countries as well as the various stakeholders. It is important that conflict management techniques are chosen to be relevant to the region. Similarly, capacity-building programmes should consider the benefits of professional facilitators from the region. Local Facilitators To ensure acceptance of conflict management techniques it is important that facilitators and mediators be regarded as competent in the region. For this reason they should as much as possible originate from the region. Capacity building programmes should take into account the need for professional facilitator/mediator training for the region. Local Government & Conflict Management Local governments are often the weak link between the strong national agencies and the stakeholders in projects. In wetland management projects the local governments are likely to be responsible for key components of project execution. It is at this level, however, that capabilities in effective conflict management are relatively weak. Wetland managers could take this into account in its capacity building programmes as well as in the support to pilot projects dealing with conflict management in wetland management. Participatory Development Some recommendations: Encourage grassroots documentation, by and for people at grassroots level providing the time, incentives, and examples that will facilitate the exchange of experience at grassroots level Shift from the dominant language, so as to enable the research and recording of experience and documentation by local people HEPPAP – Course 1. Organisations, Collaboration and Conflict Management Page 12 Develop non-traditional forms of documentation, that will be more compatible than written text and books with the local modes of expression Encourage translation from local languages, providing resources and capacity building so that local communities and instances can communicate Increase the priority of information management, starting from the beginning of the project conception Setting an example of sharing, both of successes and failures to prevent knowledge concentration as a means to gain power Recognise ownership, of contributions at all levels in respect of the ethics of data and information collection The Project Cycle Conflict management is to play a role, depending on the stage in the project cycle: Policy and Strategy Definition. All stakeholders should increasingly access meetings, conferences, seminars and workshops related to strategy definition directly. Country Programming and Project Identification. Major conflicts or conflict areas may be identified as the objective for specific supported interventions. Identification and Orientation. This is an important stage from the perspective of conflict prevention. Dormant conflicts of interest are likely to erupt. Parties may try to control or highjack the procedure. At this stage a conflict analysis or assessment is useful to provide appropriate conflict management inputs at the next stage. The conflict analysis should identify all stakeholders, past and potential conflicts among them, relationships among stakeholders and the balance of power, in relation to the identified project. The design of the conflict management process during project preparation and analysis should be based on this conflict analysis. Preparation, Analysis. Community consultation is part of the project preparation process. Consultation that aims at conflict prevention or reduction needs to involve all stakeholders early in the project design phase and clearly show how the different inputs will affect the project. The type of conflict management approach that is most effective depends partly on the existing relationships among stakeholders, but the focus is on consensus building and relationship building. A second conflict management related task during project preparation is to design conflict resolution procedures that will govern project implementation. Negotiation and Approval. If the previous stages have been concluded successfully, negotiation focuses on the conflicts of interests among the stakeholders and procedural assistance to overcome power imbalances among stakeholders. Project Implementation or Execution. Contracts and agreements do, in principle, cover project implementation. Stakeholder participation takes place as described in the project document. Conflicts are likely to be clearly defined and among a smaller number of parties. The emphasis of conflict management is on mediation and arbitration, rather than on consensus building. Project documents should have conflict management procedures built into the project execution stage, as cost-effective mechanisms to prevent escalation of conflicts at this stage. Monitoring and Evaluation. If conflicts could not be dealt with internally, monitoring or evaluation missions can be the ultimate option to manage conflicts. HEPPAP – Course 1. Organisations, Collaboration and Conflict Management Page 13