globalization (1500) A buzzword of political speech and a

advertisement

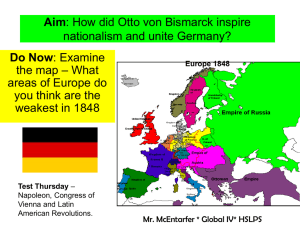

nationalism A name for the modern social and political formations that draw together feelings of belonging, solidarity, and identification between national citizens and the territory imagined as their collective national homeland. The existence and coherence of a particular nation are in this sense best understood as an ongoing product and not the primordial precursor of nationalism. But while nations can therefore be said to be made by nationalism, they are not made up. They are neither illusions nor invented like works of fiction. Although his book’s title has sometimes been misinterpreted as suggesting such an inventive account, it is instead his emphasis on the politically and socially constructive work of nationalism that is at the heart of Benedict Anderson’s now muchreprinted thesis that nationalism produces nations as “imagined communities” (Anderson, 2006). They are imagined, he argues, because nationalism mobilizes a strong but abstract sense of community between distant strangers in a way that consolidates their identification with both a common historical inheritance and a shared national space. This is also why nationalism is more social than the personal passions of patriotism and less legal than the regulative norms of citizenship, even though, as feminist and queer geographers have underlined in particular, it is clearly interwoven with each (see Bell and Binnie, 2000; Marston, 1990). In a review of his book’s many translations and globe-trotting travels that is added to the most recent edition, Anderson further documents how nationalism clearly fosters distinct national cultures of reading, writing, teaching, and communication. He underlines, too, that one of his initial intentions in the book (and one that he thinks accounts for much of its global popularity) is that geographically it shifted the focus in the study of nationalism away from Europe (and the Eurocentrism that traditional Marxist accounts shared with traditional liberal accounts) and towards various post-colonial nationalisms of the global south, including not least of all what he calls the “creole nationalisms” of the Americas (a formulation that itself also usefully undermines exceptionalist American arguments about US republicanism as the uniquely pioneering prototype of post-colonial nationalism). In making this case, however, Anderson does not so directly address the many ways in which his arguments have both resonated with and been advanced in various versions of post-colonial theory. His own attention to the role of maps and other geographic depictions in imagining the communities of nationalism clearly resonates, for example, with Edward Said’s theoretical concerns with the imaginative geographies of orientalism, including the ways in which the cultures of imperialism worked contrapuntally to construct the modernity of Euro-American nationalism by constantly contrasting the supposedly pre-modern human geographies of their colonies with the ordered and enframed landscapes of metropolitan museums, exhibitions, and textbook cartographies (Said, 1979, 1993; cf. Gregory, 1994; Mitchell, 1988). Further developing these lines of examination, other post-colonial studies of nationalism have continued to problematize the diverse geographical arguments and assumptions that continue to create hierarchies of national belonging, national achievement, and national blame in the course of imagining community. Whether it is concerns with the fate of women on the margins of the post-colonial nation (Spivak, 1992), interest in the necessarily extra-territorial affiliations of anti-racist and anti-colonial activists (Gilroy, 1993; Singh, 2004), or reflection on the historical tragedies that have led to geographies of blame for the so-called failure of post-colonial nationalism in countries such as Haiti (Farmer, 1992; Scott, 2004), scholarship addressing the imagined communities of nationalism has increasingly also problematized pre-emptive epistemological assumptions that limit national history to national geography. At the same time, work on the ways in which national geography is taught and learned in nationalist teachings themselves has also increasingly sought to unpack how the performance of nationalism can close down as much as open up opportunities for imagining territory anew (cp. Bhabha, 1994 with Brückner, 1999; Schulten, 2001; Sparke, 2005). All these post-colonial questions indicate in turn how nationalism can be implicated in racialized imaginings of space and place in both dominative and resistant ways, an ambivalence that has historically been one of the reasons why defining nationalism has been so vexing for critical theorists. As Etienne Balibar puts it with both a question and an answer of his own: “Why does it prove to be so difficult to define nationalism? First, because the concept never functions alone, but is always part of a chain in which it is both a central and weak link. This chain is constantly being enriched . . . with new intermediate or extreme terms: civic spirit, patriotism, populism, ethnicism, ethnocentrism, xenophobia, chauvinism, imperialism, jingoism . . .” (Balibar, 1991: 46). MS References Anderson, B. 2006: Imagined Communities: Reflections on the Origins and Spread of Nationalism, 4th edn with afterword. New York: Verso. Balibar, E. 1991. Racism and nationalism. In E. Balibar and E. Wallerstein, Race, Nation, Class: Ambiguous Identities. New York: Verso, pp. 37–67. Bell, D. and Binnie, J. 2000: The Sexual Citizen: Queer Politics and Beyond. Cambridge: Polity Press. Bhabha, H.K. 1994: The Location of Culture. New York: Routledge. Brückner, M. 1999: Lessons in geography: maps, spellers and other grammars of nationalism in the early republic. American Quarterly, 51: 311–343. Farmer, P. 1992: AIDS and Accusation: Haiti and the Geography of Blame. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1992. Gilroy P. 1993: The Black Atlantic. London: Verso. Gregory, D. 1994: Geographical Imaginations. Cambridge, MA: Blackwell Publishers. Marston, S. 1990: Who are “the people”?: Gender, citizenship, and the making of the American nation. Environment and Planning D: Society and Space, 8: 449– 458. Mitchell, T. 1988. Colonising Egypt. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Said, E. 1979: Orientalism. New York: Vintage. Said, E. 1993: Culture and Imperialism. New York: Alfred Knopf. Schulten, S. 2001: The Geographical Imagination in America, 1880–1950. Chicago: Chicago University Press. Scott, D. 2004: Conscripts of Modernity: the Tragedy of Colonial Enlightenment. Durham, NC: Duke University Press. Singh, N. 2004: Black is a Country: Race and the Unfinished Struggle for Democracy. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. Sparke, M. 2005: In the Space of Theory: Postfoundational Geographies of the Nation-State. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press. Spivak, G. C. 1992: Woman in Difference: Mahasweta Devi’s Douloti the Beautiful. In A. Parker, M. Russo, D. Sommer and P. Yaeger, ed. Nationalisms and Sexualities. New York: Routledge, pp. 96–117.

![“The Progress of invention is really a threat [to monarchy]. Whenever](http://s2.studylib.net/store/data/005328855_1-dcf2226918c1b7efad661cb19485529d-300x300.png)