Homology and Analogy FAQ

Homology and Analogy FAQ

If two organisms aren't related, any similarity between them has to be an analogy (or maybe just chance).

If two organisms are related, they may show both homologies and analogies.

If a similarity between two organisms is a homology, the organisms ARE related!

If a similarity between two organisms is an analogy, the organisms MAY OR MAY NOT be related.

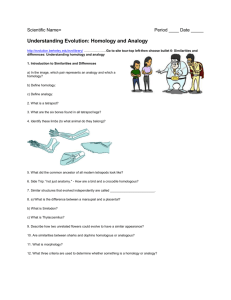

What is a homology?

A homology is a similarity in the structure of some particular part of two organisms (could be a limb, an organ, a molecule, etc.) that is due to inheritance from a common ancestor. This means the last common ancestor of the two organisms in question had that similarity in structure also, and passed it on to these two descendants. In this course, we're only going to conclude a similarity is a homology if we can't see any likely reason that the two organisms would have developed this similarity independently.

What is an analogy?

An analogy is a similarity in the structure of some particular part of two organisms (could be a limb, an organ, a molecule, etc.) that was developed independently by the ancestors of the two organisms. Why would two different groups of organisms develop a similarity in structure independently? Most likely the properties of the structure that are similar are ones that the structure has to have if it's going to serve its purpose. We will use this as our criterion for identifying analogies -- if the similarity in structure is necessary for some function, then we'll conclude the similarity is due to analogy.

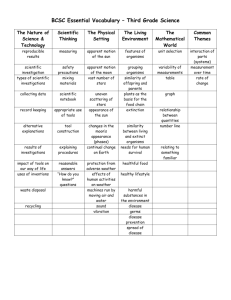

How do I decide if a similarity is due to homology or analogy?

For the purposes of this course, we use this method to decide.

Note that this decision flowchart is biased in favor of analogy -- some similarities that were actually inherited from a common ancestor will be misidentified as analogies using this chart. This means we'll be conservative about calling similarities homologies, and only conclude that when the evidence is quite strong.

Can a similarity be both homology and analogy?

Actually, no . If the similarity in structure is inherited from a common ancestor, even if it would be necessary for the function of the organ, it's still similar because they got it from a common ancestor, so it's homology.

Strictly speaking, an analogy is a similarity that was developed independently in two organisms, not inherited from a common ancestor. Now, why would two organisms develop a similar structure independently? Most likely because the structure has to be like that in order to serve some function.

However, in some situations it would be nearly impossible to tell if a similarity is homology or analogy. For instance, suppose I say that (hypothesis) mourning doves and pigeons have a common ancestor. More important, they had a common ancestor that had wings. If you look at their wings, (evidence) they have some structural similarities -- for instance, a joint (the "elbow"). Their common ancestor had this joint also, so they inherited that structure from the ancestor -- it's actually a homology, if my hypothesis is true .

By our method, though, we would say that its function is to allow the wing to bend, which is necessary for flapping to provide powered flight, so we would conclude that it's an analogy. In the strict sense, if the hypothesis is right (and it likely is, based on other evidence) the conclusion of analogy is wrong, as it would only be an analogy if the pigeon and dove had developed it independently in order to adapt to the requirements of the function .

However, in this course we're going to be very conservative about saying that a similarity is a homology, because we don't want to claim that two organisms are related unless the evidence is really strong. So, anytime we can explain a similarity as an analogy, we'll say that's what it is. We will only conclude that a similarity is a homology if we cannot explain it as an analogy .

That means sometimes we'll conclude some similarity is due to analogy when it's really homology; that's the breaks. After all, finding an analogy doesn't give conclusive evidence about the hypothesis. At least when we say something is homology, we'll be pretty sure about it.

If two organisms have a common ancestor, any similarity between them must be homology, right?

Wrong.

Suppose we have a hypothesis with everything coming from a single-celled organism. Well, then, according to this hypothesis, the pigeon and wasp have a common ancestor (somewhere after the single-celled organism). Both of them have wings (broad, thin, flat, paired structures). If the hypothesis is correct, does this mean those wings must be homologous? NO! Not unless the wasp and pigeon both got them from a common ancestor. This ancestor would have to have had wings in order to pass them on to the wasp and pigeon .

Now you can't tell what the last common ancestor of wasp and pigeon was in this hypothesis, but in the hypothesis, it was also the ancestor of all animals, including worms, ants, and dogs, for instance. It is unlikely that the common ancestor of the entire kingdom animalia had wings .

Thus, even if the hypothesis is right and birds and wasps have a common ancestor, if their common ancestor didn't have wings, their lineages would have developed wings independently, so the similarities in their wings would be due to analogy. The hypothesis would predict we'd find some homologies between birds and wasps, but not in their wings .

So if two organisms have an analogy, that means they can't be related, right?

No, that's not true. Suppose, for the sake of argument, that birds and butterflies are related, and their last common ancestor was a worm. One branch of this worm's descendants developed an exoskeleton made out of chitin, giving rise to insects. Another branch of the worm's descendants developed internal bones and gave rise to vertebrates. Eventually some of those vertebrates developed wings -- they're birds. Some of the insects also developed wings, and some of them are butterflies. If this hypothesis is right, then birds and butterflies have a common ancestor, but they didn't inherit their wings from it. The two lineages (insects and vertebrates) had

members that developed wings independently. Any similarities you would find in their wings would be analogies.

Yet they're still related. This is why we say that analogy is inconclusive -- finding that a similarity is an analogy does mean that the two organisms didn't inherit that particular similarity from a common ancestor, but it doesn't necessarily mean they didn't HAVE any common ancestors.

If it's similar by homology, must the structure have the same function in both organisms?

No.

Some of the easiest homologies to detect are similarities in structure when the structures don't serve the same function at all, or when one structure doesn't even seem to have any function .

For example, let's say one of you proposes that the tails of dogs and fish are homologous. You say they that they had "similar form, but different functions." First of all, you have to stop to define just what the similarity in structure is. What is it anyway?

Both stick out behind the organism. Both have bones in them. That's about it. What are the functions? Well, in a dog, the function is thought to be for balance. In a fish, the function is propulsion through the water. So, should we conclude that they're homologous? Maybe we should go a little further, even though the flowchart has us stop here. Is the similarity necessary for the functions? Well, the dog's tail must be somewhat stiff (contain bones) in order to stick out and provide balance. And sticking out behind seems like a good place for a balancing organ. The fish's tail has to have bones in order to be stiff enough to push against the water, and obviously you want it in back if it's going to push you forward. So in fact, what little similarity they have could be said to be simply necessary for the functions they perform, even though those functions are different .

The point here is the similarity in the tails of fish and dog is probably not convincing evidence of common ancestry .

So is analogy a similarity necessary for survival?

No.

Most of the characteristics of organisms might be said to be necessary for survival, or considered differently, none of them are. After all, wings aren't necessary for survival; We don't have any, and we are doing okay. The

"necessity" that we discuss when talking about homology and analogy is different. When we see a structural similarity in some body part in two organisms, we ask, "is the similarity we see necessary in order for this body part to serve its function?" That is, IF you're going to use wings to fly, are there some structural properties they would always have to have in order to do that? Probably so, including being thin, flat, broad, etc .

So, can I say that two organisms are homologous?

No , you're not testing whether two ORGANISMS are homologous or analogous; you're testing individual structural similarities. The wings of wasp and pigeon are probably similar by analogy. There could be other similarities, maybe in the molecular structures in their cells, which they inherited from the common ancestor of all animals, and those would be homologies. This wouldn't mean that we should then conclude the wings are homologous; it's quite possible for organisms to have some similarities they inherited from a common ancestor and some that they developed independently. We're looking at one structural similarity at a time .

I don't know enough about bird and butterfly wings to answer this. I'm looking up more stuff on the web.

Well, we never want to discourage you from seeking information, but generally, the exercises assigned in this course will include all the information you need to do them, or use just information that everyone would have.

Everyone knows enough about bird and butterfly wings to say that they're flat and thin, right? And that's enough for the purpose of this assignment. The point of the assignment was just to make sure you can apply the reasoning process to decide if a similarity is due to analogy or homology, not to make you into ornithologists or entomologists .