The Controversial Death Ritual of Sati in Hindu

advertisement

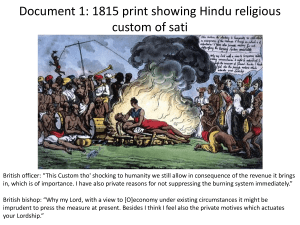

"The Controversial Death Ritual of Sati in Hindu and Indian Culture" A Sociological Research Analysis of Ancient Hindu and Indian Society, Culture, Social Stratification, and Art Theodora Moses 515 Mullica Hill Road Apt D209 Glassboro, NJ 08028 mosest45@students.rowan.edu (732)673-9918 Prepared for the course “Sociology of Death, Dying, and Bereavement” 2 Abstract Sati is the ancient custom of widow Hindu brides following their husbands into death by burning themselves alive on their deceased husbands’ funeral pryes. It was a socially accepted and ritually approved sacrifice that brought a great deal of honor to the widow’s family as well as exalting her to a goddess like position post mortem. While the actual occurrences of recorded official satis are few in number, it is not the frequency of the ritual that is significant. The society of ancient India which allowed and supported this fatal ritual is what needs to be analyzed. The social and religious context in which this ritual occurred will be examined in depth. The debate will be examined from both sides – the supporters of the right to commit sati as well as those who are adamantly against the ancient now outlawed practice. The method for analysis that will be used for this discussion and analysis is that of scholarly interpretation coupled with sociological theory. In addition, Sati as a ritual was portrayed frequently in ancient Hindu art and a careful analysis of the social and religious meanings in these works of art will be discussed and exhibited in the poster portion of this research. 3 Sati is the ancient custom of widow Hindu brides following their husbands into death by burning themselves alive on their deceased husbands’ funeral pryes. It was a socially accepted and ritually approved sacrifice that brought a great deal of honor to the widow’s family as well as exalting her to a goddess like position post mortem. While the actual occurrences of recorded official satis are few in number, it is not the frequency of the ritual that is significant. The society of ancient India which allowed and supported this fatal ritual is what needs to be examined. The woman and ritual were endowed with such a great amount of social prestige that every single Hindu caste has reported cases of sati. The social and religious context in which this ritual occurred will be examined in depth. The debate will be examined from both sides – the supporters of the right to commit sati as well as those who are adamantly against the ancient now outlawed practice. Sati as a ritual was portrayed frequently in ancient Hindu art and a careful analysis of the social and religious meanings in these works of art will be discussed. The method for analysis that will be used for this discussion and analysis is that of scholarly interpretation coupled with sociological theory. The actual word “sati” is derived from the Sanskrit root meaning “truth”. Sati is used when referring to the ritual itself as well as the widow who commits it. So how did this ritual begin? It is not entirely clear, but there is an accepted myth that tells of the origin of sati in India. The origin myth states that the goddess Sati burned herself alive outside of a ceremony being given by her father as a sign of protest and loyalty to her husband, the god Shiva, as he was not permitted to attend or invited to take part in the ceremony being given by her father. The goddess Sati was proclaimed to be the prototype 4 of wifely virtue (Stein 467). Greek travelers to India have reported witnessing the ritual first hand as far back as 4th century B.C. Hinduism and its views of women plays a very important role in the support of the ritual of sati. The way in which women were viewed as well as belief in the afterlife made sati a reality. It was believed that women possess a greater amount of energy than men. This great energy was considered wild and in order for a woman to safely be a part of Hindu society this energy had to be harnessed to a man so he could safely direct it. It was believed that the energy of female children was harnessed by their fathers, and when they were married off this energy would continue to be harnessed by a male figure of authority throughout their lives. This female energy supply, called “shakti” was considered to be “ardhang”, meaning although this energy was great it only constituted half a body’s worth of energy. Only when she was married would her energy be complete, thus a married couple was viewed as being a single bodily unit and not as individuals. If a married man were to lose his wife to death he was permitted and encouraged to take a new wife, replacing the lost energy and becoming whole once again. If a married woman were to lose her husband to death she was not permitted to remarry under any circumstances. She was considered uncontrolled and dangerous, as her energy was no longer harnessed to a man, thus justifying the ritual of sati. “After the death of her husband, she is especially dangerous and must shave her head, cake it with mud, sleep on a bed of stones…If a widow is chaste and young, she is so infected with magic power that she must take her own life” (Stein 468). The reason for her being unfit to remarry was that her body was now considered unchaste, the epitome of female wickedness in ancient Hinduism. Women’s bodies 5 commoditized so much so that once she has been married she could never again be “used” by another man. “Like a dining leaf used previously by another person, she is unfit to be enjoyed by another person” (Stein 468). Not only was the woman considered to be inferior to her husband, her entire family was looked down upon as well. Upon her marriage, a Hindu woman became a part of her husband’s family. If and when her husband were to die she was then a burden on her in laws, and due to the patriarchal nature of ancient Hindu society there was no longer a place for her in the world (Stein 469). In addition to the position of women in Hindu society as a contributing factor to the acceptance of sati was the religious support given to it by Hinduism. The Hindu religion has strong belief in the life hereafter. The ancient interpretation of the life hereafter was that one’s life after death was only as complete to the extent of which the whole environment of the deceased was transferred into death with them. If a deceased man were to be cremated without his property, including his wife, then his life in the hereafter would not be whole or complete. This belief evolved over time from future life replicating life in this world “into the view of future retributive justice” as in the theory of karma (Fisch 305). Interestingly enough, at this point the practice of sati did not end. A new definition was given to sati. It was no longer her obligation to follow her husband into death so that his after life would be complete, it then became the wife’s duty to liberate her husband and achieve an increased sense of morality for her family. The actual ceremony of a sati was very elaborate and ritualistic. To begin with, a woman was not allowed to burn if she was unfaithful to her husband. It was required that she be in a state of ritual perfection and purity upon burning. This meant that if she was 6 menstruating, she would not be allowed to go through with the sati as menstruation was considered a temporary sign of being unchaste. Her voluntary self immolation and self sacrifice was considered to be a sign of her constant and unwavering devotion to her dead husband. The procession to the cremation ground included the widow and the body of her dead husband as well as Hindu priests, mourners, and often times an excited crowd. Due to the fact that satis were rare religious events it was not uncommon to find a large and eager crowd gathered to see this divine and devout ritual. The sati herself would be adorned in an elaborate gown and jewels, which she was to distribute along with money to the witnesses in the crowd. Upon her death she was exalted to the status of goddess, given the power to curse as well as to bless. The crematory funeral pyre was likened to the couple’s marriage bed and after the ritual was complete the location of cremation became a local shrine dedicated to the now considered saintly and glamorous sati (Stein 473). It is important to further address the position of women in ancient Hindu Indian society. Without the level of social inequality through which they were viewed, the practice of sati would have never come to fruition. A married woman that had sons was regarded highly and with much veneration, however if a woman was unmarried or widowed she was suspect and all together dangerous. A Hindu woman was quoted as saying “’We are not like you. In our society, we do not live alone’” (Stein 484). Marriage was the only way that a woman could become to be considered a functional part of Hindu society. Without marriage, she was not even considered to be a socially active being. This inequality impressed upon them every day of their lives taught and conditioned them that it was their duty to follow their husbands, even into death, and by doing so they were 7 preserving society. Just as social stratification of the castes dictated that lower castes must follow higher castes this inequality was translated to women (Fisch 300). The prestige that came along with committing the ritual sati was institutionalized and recognized by every caste. It was a telling expression of the power struggle between men and women. Becoming a sati and choosing to die and burn along with her already dead husband was the only chance for a woman to gain esteem. She brought value and prestige to her family and herself came to be considered a goddess. Debate continues to thrive in regards to the ancient custom of sati, almost one hundred and eighty years after its initial prohibition. During the British colonization of India sati was prohibited initially in 1829. Western outrage and astonishment at the seemingly brutal practice caused Indian princes to follow suit and prohibit the ritual officially in Indian law in 1862. Despite its prohibition it lingered on for decades, surfacing as recently as 1987 (Fisch 293). It is difficult to report officially documented cases of sati due to the controversy and remote locations often surrounding the ritual. After the state made it illegal the social tolerance and acceptance of this ritual allowed it to live on. Sati became an issue of great concern, a crime in eyes of the state versus a prestigious religious tradition that must be kept alive in very devoutly religious and traditional circles. Estimates range from satis being committed by one out of thirty six widows to only one in one thousand. The average age of officially confirmed satis ranged from twenty one to sixty years old, with an average of 2.3 surviving children for each documented sati. Again, the significance of this ritual does not lie in the statistics, rather in lies in the symbolic and social context (Fisch 295). 8 Those who favored sati conceptualized it as being the ultimate connection of this world to the next, an aspect that is central to Hinduism. While it does reflect, confirm, and strengthen the subordination of women it was also seen as having a higher, more divine purpose. Advocates for this voluntary self immolation of widows regard it as being respectable religious act protected by religious freedom. It is seen as a rare miracle, a divine event that should not and perhaps even cannot be understood by human standards or judged by mortal law. A sati and the ritual of sati are symbols of ultimate bravery, faithfulness, and chastity (van den Bosch 181). This divine act is seen as entirely voluntary and a free willed self proclamation of heroinism. The opposition and outrage that surrounds sati is founded in the belief that a sati could not have been voluntarily committed by a Hindu woman due to the inherent patriarchal and discriminatory nature of their society. Was it a divine act, or “only a social evil and a crime, characteristic of a culture which is dominated by blameworthy ‘macho-values’ presenting themselves disguised in a religious luster of holiness?” (van de Bosch 185). The culture these women lived in was one of great inequality. Opponents of sati see women as victims of society, a society so imbued with violence that her going through with her own self immolation should be viewed as a symbol of structural violence and not as a voluntary action. Sati was not considered an act of free will but rather either a cruel murder or stubborn suicide. The immense psychological pressure felt by a widow both from her in laws as well as her religion would force her to comply in following her husband into death (Fisch 324). In traditional Hindu society there was no such thing as “free will” for women. They had never been taught how to make an 9 independent decision and it is conceivable that they would be unable to grasp the concept of making an independent decision. Upon her husband’s death, a widow was faced with no other alternative that to submit to what society told her to do, what she had been taught was the ultimate divine act. She was forced to choose between physical and social death, the latter of which being the only true threat. Physical death in the Hindu religion was nothing to be feared due to a strong faith in life after death. To die socially in Hindu society would be a traumatic and tragic death. The woman would be treated by the members of her community and society as dangerous and unchaste, a disgrace to her family and a worthless nuisance. She would be dead in the eyes of others by choosing to violate a cultural and religious rule so central to her identity in society. In 1987, the most recently documented and publicly recognized sati was committed. This occurred one hundred and forty five years after it was prohibited by Indian princes, and produced an understandably huge backlash in modern society both within the Indian culture and across the Western world. The days of female inequality were supposed to have been a thing of the past, a distant memory of the once oppressive and violent nature that discriminated against Hindu women in India. On September 4, 1987 recently widowed Roop Kanwar self immolated herself and became a sati at Deorala in the state of Rajasthan. The practice of sati was thought by most of the world to be a thing of the past, but this highly publicized sati transmuted a cultural stereotype that was thought to be long extinguished, and was called “the barbarity of a primitive practice that blemishes the face of Indian democracy” (Weinberger-Thomas 89). The statistics tell us a very different story. Conservative estimates state that between 1943 and Roop’s very 10 public sati in 1987 that some thirty women committed sati in the state of Rajasthan alone (Weinberger-Thomas 182). So why did all of those satis go unnoticed by the world media, what was different about Roop Kanwar that garnered so much exposure and reciprocal public outrage? Roop Kanwar was only eighteen years old when she took her own life. She and her recently deceased husband had only been married for eight months. He was twenty four years old, six years her senior. His death was extremely sudden occurring only days after a sudden illness and hospitalization. She had no children and her family approved of her decision and shared in the triumph of her heroic deed which was considered to be a rare divine event. She was given the title “sada suhagan”, a wife whose husband lives, and “sati mata”, pure mother. Immediately following her death, people questioned whether she willingly volunteered or was coerced into becoming a sati. Eleven people were charged due to their connection with the illegal and very public ritual but were later acquitted (Hawley 13). Roop Kanwar’s sati relit the fire concerning the controversial ritual, which led to The Commission Of Sati Prevention Act, “an act to provide for the more effective prevention of the commission of sati and its glorification and for matters connected therewith or incidental thereto” (Weinberger-Thomas 194). Sati as a Hindu death ritual was portrayed frequently in art throughout history. Analysis of the manner in which the ritual is portrayed is very telling of the society of the time’s perspective and opinion regarding sati. In a monochrome of Sarasvati Sati, a sati is portrayed in the manner most representatively and of common practice within Hindu art. The woman committing the sati is pictured; hands poised in prayer, with a calm and serene look in her eyes. The light that encircles her head as she prays signifies her newly 11 attained holiness due to the divine nature of the sati. Under the flames which are small, controlled, and flowery, you can make out her dead husband’s face. The sun’s rays penetrate the flames, acting as a divine match stick of sorts to ignite the holy sacrificial fire. Two Hindu gods emerge from the clouds to bless the sati in her ritual, and the swastikas are a Hindu holy symbol (Weinberger-Thomas 117). The picture is beautiful, serene, and holy – much reflecting the acceptance and practice of widow burning in ancient Hindu culture. Art is by no means imitating life in this case as we are able to see in an actual photograph of a sati. Here we see a photo of Jasvant Kanvar on her husband’s funeral pyre. The veil that covers her head is red which is a symbol for marriage in Hinduism. The woman’s arms emerge out of the pile of coconuts holding her down, her palms up and facing the sky, also a Hindu religious symbol. Her husband’s body and face are unintelligible, but in the background you can see the bodies of at least 3 or 4 people immediately next to the funeral prye, either active in the ceremony or onlookers. The comparison of painting to photograph shows the drastic difference between Hindu perception of sati, the ultimate holy and blessed event, to the reality of it – a woman being burned alive as people stand by and watch. To compare Hindu art depicting sati to art rendered by Europeans depicting the same act contrasts drastically for obvious reasons. The socio-religious meaning and symbolism given to and surrounding any ritual or act is entirely dependant upon the values of the society it has been created by. To outsiders, sati is a brutal and cruel sacrifice, contrary to the Hindu conceptualization as a divine self sacrifice. If one did not know any better, it could easily be assumed that the manner in which “The Story Of Baptist Missions In Foreign Lands” (1885) portrays sati, it is the tribal murder of an arch 12 enemy (Barns). Here we view a large crowd of Indian natives adorned simply in loin clothes surrounding a huge fire on the banks of a river. Flames leap towards the sky and dark billowing clouds of smoke rise up, to a sky vacant of any religious symbolism or Hindu gods looking down with approval. The widow lies face up on top of the flaming funeral prye, her husband no where to be seen. Her arms are crossed over her chest, her face reveals nothing. Many members of the crowd stand with arms outstretched upward, signifying a sense of excitement. In the background the outlines of a village are apparent. This European, outsider portrayal of the ritual sati, or as the they called it “suttee”, show it for what it appears to be to them – a ritual sacrifice of a human being, not framed within any religious context. The controversial practice of widow burning in ancient Hindu tradition has yet to completely fizzle out. As recently as 1987, within this lifetime, an eighteen year old woman killed herself in honor of her husband and family in the form of sati at her husband’s public cremation. Addressing the issues of social inequality, religion, the stratification of gender roles, and the use of art as interpretation close out this research with no real answers of right versus wrong, religion versus state, or voluntary action versus coercion. What we can conclude is that the society and culture that it constructs give meaning and to every single aspect of that society. 13 Bibliography Fisch, Jorg. “Dying for the Dead : Sati in Universal Context”. Journal of World History. Vol 16, No 3. 2005. pp 293-325. Barns, Chancy R., Rev. G. Winfred Henrvey. “The Story of Baptist Missions in Foreign Lands”. 1885. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Image:Hindu_Suttee.jpg Hawley, John Stratton. “Sati, the Blessing and the Curse : The Burning of Wives in India”. Oxford University Press, 1994. Stein, Dorothy. “Burning Widows, Burning Brides : The Perils of Daughterhood in India”. Pacific Affairs. Vol 61, No 3. 1988. pp 465-485. van den Bosch, Lourens P. “A Burning Question : Sati and Sati Temples as the Focus of Political Interest”. Numen. Vol 37. 1990. pp 174-194. Weinberger-Thomas, Catherine. “Ashes of Immortality : Widow Burning in India”. The University of Chicago Press, 1999.