Notes for 2015 AAA paper on ritual discourse and gender in Japan

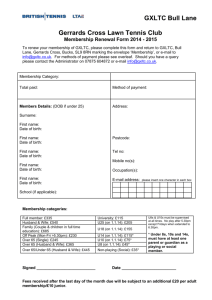

advertisement

「戦後、強くなったのは靴下と女性」 Sengo, tsuyokunatta no wa, kutsushita to josei, which first I heard long ago as “Two things got stronger after the war, women and nylons,” can get us started, at least, and if anyone can trace this meme of Japanese women’s growing strength back farther, in the way Robert Merton tugged at Newton’s “If I see farther, it is because I stand on the shoulders of giants,” I will be glad to hear about it. I am not entirely sure we have a definition of ritual that will let us include the public discourse this Japanese expression captures, but the debate over, or even assertion that, women’s power is growing to the extent that it eclipses that of men in some spheres of social life if not all, seems to me to fit in with that broad category of social phenomena which persist without evidently accomplishing their goal, or acquiring a resolution, or simply, stopping. And so we are thrown back on the idea that either we do things all the time that are irrational and that even knowing they are doesn’t put a stop to them, or else that the activity is symbolic. And having then gone the next step to note that they are merely symbolic, we can end our analysis, take a deep breath, and get on to something important. But this is a debate that is really no debate, and no one who is not part of it can possibly be fooled. Over the last several surveys, the UN rankings for gender equality have consistently located Japan at the very bottom of the wealthy world, most recently number 104. This is the same sort of debate that finds the world’s best health care system in the US with infant mortality at 34, just below Cuba, but ahead of Malta. Any disinterested observe must conclude that something important is missing from the public presentation, the core of the tale of the Emperor’s New Clothes. Following on Ortner’s formulation of Male is to Female as Culture is to Nature, Lamphere examines in further detail the Rosaldo’s 1974 formulation of the widespread analogy found in Japan as well, Male is to Public and Female is to Domestic, showing that this formula leads not to a balance of power or even a relation of necessary equality required to make a teeter-totter work, but systematic inequality. And yet, there is enough still missing within this formulation, as Rosaldo not just recognize but demand that this relation is not one of necessity or a biological imperative, that Ogasawara could find the issue compelling enough to try to understand the question of men’s and women’s power relations that she could not resolve the matter in her own mind based on her own subjectivity until she undertook systematic fieldwork as a participant observer as an Office Lady in a major Japanese bank. The ingredient I want to add here from Bell is the inherent political component of ritual, symbolism in action. As Bell puts it, ritual is “power relations in action” and thus is inherently political. But if ritual is inherently political, politics is not an activity confined to the legislative halls of national governments. There is a political dimension to every human activity. Politics identifies the social contention raised over how the activity should be conducted or how the activity should be framed. Politics and ritualization can thus be seen as locked in an eternal dynamic: one questions and contends while the other, in reaction to this contention, attempts to assert that some things are beyond question. But power is illusory. It is easy enough to say that people want their own way, and that what they do get is a result of not just what they do to accomplish their aims, but what others do in response. Yet this is not all simply struggle. People can also support one’s aims and lend a hand according to their own lights. And so, if people do want to get things done socially, and they cannot do this by exercising power, what can they do? This is the question, really, what do people do to get their way, knowing that the results of their efforts depend on what other people do in response. What seems to distinguish routine from ritual to me at the moment is that routine is an established practice that gives the results aimed at, while ritual relies on symbolic action, putting symbols into action. Perhaps in this instance I am relying on American culture’s first order assertion that symbols are not as important as what they stand for or point to. But in addition to Bell’s recognition that ritual is a way of getting one’s way, I want to draw on Paige and Paige’s notion that how rituals of reproduction at least work is in part by misdirection, and this idea seems to gain significant comparative support as well, that the relations among categories of thought that symbols create for us can be forged while we are looking in a different direction entirely. Maybe this is a key to “false consciousness,” but in any event, it is clear that in so far as symbols structure cultural knowledge by similarity, to the extent we focus on those similarities, are attention is drawn away from those areas of difference hidden by our analogies. When we have positive knowledge, cause leads to effect reliably. When we act on analogies, we put our confidence in the web of relationships among the categories of thought that make up our culture and so reproduce those relationships once again. In Paige and Paige’s view, ritual lets us do so without becoming aware of the ways we are recreating the social relationship supported by the rest of culture. The basic misleading structure is Male : Female :: Public : Private :: Breadwinner : Homemaker, which frames the debate around gender construction and roles. The illusion, of course, is that in modern industrial society the idea of the Private has a stream of resources that originate somewhere other than in the Public. When we look into all those households in which the household is still the basic formation of production, the picture is entirely different, and it is this situation that gave rise to the current pattern. Women are not heads of households and where there are daughters but not sons in households that require a successor, adult men are frequently adopted, not women except in the water trades in which women cater to men who provide their income. Amayakasu position and superiority: How to reconcile or understand the contribution of the amaeru relation between wives and husbands in the home. The person who indulges is the superior. The subordinate shows the need for affection and the superior recognizes that need and fulfills it by indulging the subordinate: it is not all iron discipline. There is a good deal of “boys will be boys” to this, “wanpaku boya.” So it makes sense then when we see the wife indulge the husband at home, that the wife treats her husband from the position of wife, as the mother treats her children from the position of mother. Certainly this makes it seem as tho the wife is the superior at home. And yet, is there any sense in which we can think there is an iron hand in the velvet glove. There might be with a child, certainly in the threat to leave a child or abandon a child, to exclude the child, to call the authorities to take the child away. But can this work with the husband? Or is this same technique of indulging, also called mothering, the only technique available to wives for husband management? What could she do that would discipline the husband that would not at the same time draw widespread criticism to her? To be a wife is to indulge her husband, and that is the only technique she has. She must either absorb his behavior or subject herself to external criticism for her selfish and ungrateful treatment of him. How does she get her way? Where is the power, her ability to get her way despite her husband’s resistance? This is not the same as having cultural permission to do the best job she can as household manager and a wide latitude to do so with autonomy. That a husband has learned helplessness does not authorize her not to boil water when he wants it or needs it within the conventional role relation, eg, when he returns home late from work. We have to conclude that the relation between husband and wife is not the same as that between the chief of staff and the “young officers.” While he can individually discipline any officer, he needs the support of the large majority of his officer corps to remain legitimate. This is not the case with husbands and wives. When I first arrived at Kyoto University’s Primate Research Center and got to know the graduate students, I learned that they routinely sneaked into the director’s office and took bottles of whiskey he had been given as presents. People gave him the whiskey and the graduate students drank it. In the three years I was there, no notice was ever taken of the practice, and it continued steadily. The students always acted as tho their act was undetected and was exceedingly clever of them. This seems to me a fine example of amaykasu. At first I thought this faux-debate was a sort of accusation, a limitation or a tether, like an invisible fence, that saying women were more powerful than men, when they clearly were not, anywhere, was a way of saying women had gone as far as they were going to go. Rather like a university president recently said to her faculty as they began to organize a union, that that would spoil the relationship between the faculty and the administration. Certainly the attenuated feminist movement of the 70s gives this impression, except that so many women seemed to agree then, as with the use of the word “proxy” rather than the conventional word “representative” (daihyō) by women who ran for office in association with the Seikatsu Club Seikyo movement. And even in the present the conception of housewife in Japan seems to get more than nothing from the conception of “professional housewife,” to the extent that women are reviving the popularity of this role in increasing numbers. (see Nippon.com article) Start