Andrew P

advertisement

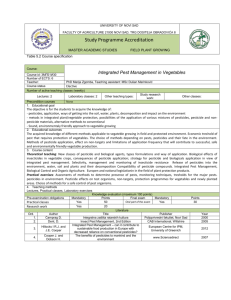

Andrew P. Flynn ATL 110, Section 009 Frank C. Manista, Ph.D. November 26, 2002 Pesticide Usage and the Issues Surrounding It Pesticide use in the United States is constantly in the spotlight. Environmentalist groups are always quick to criticize usage and they make sure that the media their local government hear about it. But, is all the controversy really necessary? It is true that the public perception of pesticide use is not a good one. The reason for this is that the majority of people are uniformed about pesticides and their effects on the environment. The public has been given this perception through media coverage of extreme environmentalists saying that pesticides are killing the environment and ourselves. “We live in interesting times when the truth and public perception on environmental issues are shaped more by the media and special interest than science and reason” (Kenna 1). In reality, if people were better informed about pesticides, they would know that when pesticides are used in a correct fashion, the majority of the effects are positive for the environment and ourselves. “It only takes one extreme environmentalist to blow things out of proportion in order to get support for their cause. There is a tremendous misunderstanding in our society about pesticides” (Maloy 27). However, the trend is that most people will more than likely think of pesticides as a danger to society. What impact will all these negative perceptions create for the future of pesticides? Are there any alternatives to pesticide use? To better understand pesticides and the debate surrounding their usage, it is important to look at the history and the background of these products along with the current regulations imposed on pesticides. Flynn 2 Pesticides are chemical agents for controlling pests; they include herbicides, fungicides, insecticides, and nematicides. The first recorded use of a pesticide dates back to 1200 BC when biblical armies would cover conquered fields with ashes and salt, making the soil unable to grow crops. Pesticides have come a long ways since those times. Instead of just applying a certain element or compound to the soil to control pests, technology has allowed chemists to create all sorts of organic compounds which are very site specific. For the most part, pesticides are organic compounds that interfere with some physiological process in the pest organism. To work properly, a pesticide must be present at the site of pest activity at an effective concentration and for a sufficient time period. Pesticides are mainly used in three different agricultural industries. The most important usage is in the farming industry. Insecticides save crops from insects, fungicides save crops from disease, and herbicides control weeds. The other two industries in which pesticides are used are in horticulture and turfgrass management. In the opinion of the public, this is where the issue lies when it comes to pesticides being a threat. Because having green grass and a beautiful landscape is not essential for sustaining life on earth, pesticides tend to get a bad wrap in these industries. In particular, the turfgrass industry receives more negative attention for pesticides use than any other. Reasons being are that humans and wildlife are always in close contact with turf. Whether it be on a golf course, a sports field, or even a home lawn, humans are in constant contact with the turf. The fact that pesticides could pose a threat to humans has brought about many changes within the pesticide and pest management industry. In 1970, the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) was formed. The EPA was responsible for all registration of pesticides. In 1972, Congress passed the Federal Environmental Pesticide Control Act (FIFRA). This act was passed Flynn 3 to assure that all chemicals being applied as pesticides would not pose a threat to the environment or any non-target species. “These products are biologically active chemicals and, if they are misused, can cause damage to human and environmental health” (Grodner 28). The largest impact FIFRA had on the pesticide industry was that it required a label to be put on every pesticide that is registered. When the pesticide is used according to the label and all directions are followed, the application of the product should be relatively safe. Also, under Section 23 of FIFRA, it was agreed that it is the states’ responsibility to implement these laws and regulations and to educate commercial applicators. This eventually led to FIFRA regulating the use of the potentially more harmful and dangerous chemicals, often referred to as Restricted Use Pesticides (RUPs), to certified applicators. In order to become a certified pesticide applicator, there are several courses and tests that must be completed. These tests are to ensure that if a RUP type chemical is being applied, a trained professional that is aware of the laws, labels, and restrictions is the one who is applying it. “The regulations require commercial pesticide applicators to demonstrate competency in the following areas: label and labeling comprehension, safety, environment, pests, pesticides, equipment, application techniques, and laws and regulations” (The Urban Pest Management Council of Canada 49). In addition to all those areas, the applicator must also be able to demonstrate competency in the specific category in which they wish to be certified. For example, someone spraying for insect must be certified to spray insecticides. In one way, theses regulations benefit the public and the pest management industry, but with the way things are going today, many current regulations are hurting or attempting to hurt the industry. From coast to coast, legislation directly affecting how the pest management industry does business is working it way through the government. Some legislation is good for the industry Flynn 4 and some is bad. In Arizona, citing provisions “that could put 200 pest control companies out of business,” Gov. Jane Hall (R) vetoed legislation that would have put additional requirements on pest management companies. This would have marked the second major revision to the state’s Structural Pest Control Act in the last three years. In Alaska, legislation requiring commercial applicators to post signs before even applying the pesticide and also requiring companies to submit comprehensive records on an annual basis to the Department of Environmental Conservation also failed to pass. These are just a couple examples of how close the pest control industry is to losing some of their rights to do their jobs. “What is important is the need for pest management professionals to become active in the political process to help protect the industry’s future” (Harrington 6). Without active participation by supporters of pesticide use in these political processes, these types of legislation will eventually be passed. Some legislation has already been passed. “Approximately 42 states have laws or attorney general opinions giving state pre-emption in pesticide regulation and/or that local government agencies cannot pass regulation that inhibits use of pesticides by the public. However, local activists continue to press for regulation or legal roadblocks against registered uses of pesticide and fertilizer products” (Higley 10). In Boulder, CO, the city has stopped all pesticide use until the city council can fully review activist request for a permanent ban. In Carbon County, PA, the county has banned the use of right-of-way herbicides. Right-of-way herbicides are the weed killers that any non-certified person can go out and buy at their local convenient store. In Suffolk County, NY, activists are suing to stop mosquito abatement applications. Frank Gasperini, director of state issues for Responsible Industry for a Sound Environment (RISE), states, “Pre-emption is critical, because if local governments can pass pesticides regulation, we would see a patchwork of different and contradictory laws that would Flynn 5 not protect the public and would make the business of supply and use of pesticide products nearly impossible, while denying citizens the right to protect their own property” (Higley 11). Because these new regulations seem to keep coming, it is important to begin to think of some alternatives to pesticide usage. The two main alternatives to spraying pesticides would be using biological control methods to overtake the pest or by using integrated pest management (IPM) which would also control pests. Biological controls would consist of introducing an opposing species of the pest in order to run out the pest or destroy it. This works good sometimes, but could have negative effects when the species that has been introduced to the pest becomes more of a problem. It is not near as effective on pests as pesticides are. IPM consists of minimizing the use of chemical practices and concentrating more on cultural methods to control pests. This would include things such as pruning a dead branch off of a tree, mowing the grass at a certain height to minimize risks of infestation, or by using any type of preventative measure to try to keep a pest out. In an article by Austin Frishman, “When Not to Spray, Yet Achieve Success,” he explains in a list, ways of when not to spray pesticides, yet still control the pest. For example, when fruit flies are living around a trash basket, remove the trash, clean the container, and use an insect light trap to capture the adult flies. He also lists several more situations that when one understands the biology of the pest, there is no need to use pesticides. “There are many situations where the use of some pesticide is necessary. I just wanted to give some examples of why we do not grab for the can and think later” (Frishman 9). With the constantly changing laws and regulations in the pest management industry, the future of pesticide usage could go in one of several directions. New products, new pests, and Flynn 6 new technologies will contribute to which direction pesticide use will go. Some of these changes are for the better, and few are discouraging. One thing is for certain, change is inevitable. The Food Quality Protection Act of 1996 has created a bit of uncertainty for the future of pesticides. This new laws differs from some what similar past laws in that it looks at the cumulative affects from exposures of all pesticides with similar modes of action. Past laws would just look at short term affects of any type of pesticide. Because of newer technologies, researchers can now narrow pesticides into specific groups and do long term research on their affects. “The Food Quality Protection Act will march on. Its overall impact is uncertain, but without a doubt, we will see some loss of pesticide products for use in the landscape” (Brandenburg 104). The only bright spot for the future of pesticide use is in the new technologies and new chemicals being created. “Most of the newer products we see introduced into the market are less toxic to people and wildlife than are many of the products these new introductions are replacing. As technology continues to improve, we’ll see more advances in that direction” (Brandenburg 106). “The spectacular growth and development of synthetic organic pesticides that has occurred since mid-century has been accompanied by equally noteworthy benefits in managing pests of crops and forests, in dairy and poultry production, and in control of vector-borne diseases” (Plimmer 645). Analytical chemistry and pest biology are important factors in the direction of pesticide design. Environmental issues have been turned into regulatory requirements. As a result of this, major objectives of pesticide design focus on creating more environmentally acceptable compounds, the improvement of selectivity of the compounds, and a reduction of the dose required for an effective treatment. These are all positive steps for the industry. Technology has also allowed chemists to create pesticides made from natural products or from Flynn 7 engineered organisms. These products appear to have a lot of promise for the future, but currently, they often fail to meet pest manager’s expectations. The future of pesticides appears to have its advantages and disadvantages. Laws and regulations are calling for safer and lower dosages of pesticides, and with newer technologies, it will be possible to make these pesticides effective. However, these laws and regulations are also limiting and banning effective pesticides. Can pesticides really be that bad in which it is required to ban their usage? The EPA requires hundreds of tests and it takes over ten years for a pesticide to even be granted registration for the marketplace. In research done by the USGA environmental research group, place where long term pesticide use took place are far below dangerous levels (Kenna 1). It is certain though, that there will always be a demand for pest management, and while there is that demand, pesticides will continue to be used.