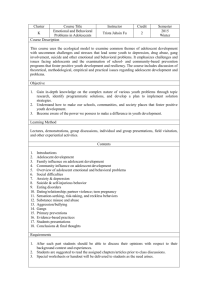

Several international documents provide the policy

advertisement