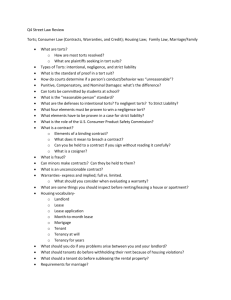

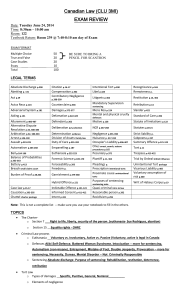

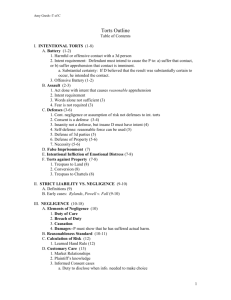

Torts Generally - NYU School of Law

advertisement