CITY PROFILE OF KOLKATA

advertisement

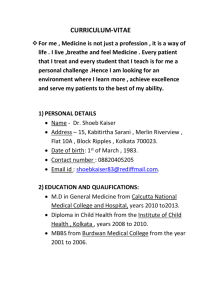

Kolkata water profile: City of joy weeps for water Adversity in spite of abundance. That’s how Kolkata’s water situation can be summed up. The city has access to plenty of water, but its worn-out delivery network results in inequitable distribution. Worse, drinking water gets contaminated, resulting in frequent outbreaks of water-borne diseases… Kolkata (formerly Calcutta) was founded in the late 1600s by the British settlers who arrived with the East India Company. The city probably derives its name from Kalikata, one of the three villages on which it came up, which was famous for a temple dedicated to Goddess Kali. The city has a history spanning over three centuries and was the capital of British India from 1773 to 1911. Over the years, Kolkata, , which is the capital of West Bengal, has grown manifold to become one of the biggest cities in the world. The latest expansion of the city limits took place after the Kolkata Municipal Corporation Act, 1983, was passed. It included the municipalities of South Suburban, Garden Reach and Jadavpur within the Kolkata Municipal Corporation’s jurisdiction, which now spreads over 18,733 hectares, consisting of 141 wards. River Hooghly flows past the western part of Kolkata and the South 24 Parganas district forms the southern and southeastern boundary. The North 24 Parganas forms the eastern and northern limits of the city. Inadequate civic infrastructure The civic infrastructure of the metropolitan area is not adequate to cater to the city’s growing population. Unplanned development for the better part of the city's three centuries of existence has taken its toll. The shortage of funds and low revenue generation has also affected development work. Housing shortage has resulted in the growth of slums. Roads are few while the traffic has increased tremendously. Public transportation is extremely crowded. Sanitation, water supply, pollution, health, access to education and the state of the economy are major areas of concern. The demographic density during 1981 was 22,260 person per sq km and during 1991 this rose to 23,670 persons per sq km in Kolkata. WATER SUPPLY STATUS Paradoxical situation1 Water scarcity in a city like Kolkata, which is situated in the lower reaches of one of the world’s largest delta regions, may seem paradoxical. Though Kolkata has a fairly abundant source of surface water close by, the community water supply system suffers from problems of poor maintenance, inequitable distribution and poor quality management. Kolkata residents get more water than their counterparts in other metropolitan cities. But, the abysmal quality of water makes it a serious health hazard. An inadequate and worn-out distribution system coupled with poverty and squalor in the innumerable slums and squatter colonies adds to the problem. As a result, outbreaks of waterborne diseases and epidemics because of faecal pollution of drinking water are alarmingly frequent in the city. Water sources The residents get their water supply from three main sources: The KMC supplies treated water through an underground pipeline network The roadside public bore wells that KMC has dug The innumerable private bore wells that the residents have dug up. Though there is no dearth of water, the city does not have enough resources to treat it or maintain and manage the distribution system. Enough water, claim authorities The conference of secretaries, chief engineers and heads of implementing agencies in-charge of urban water supply and sanitation held in May, 1989, had recommended a minimum per capita water supply of 150 litres per day, including losses for Class I cities. Earlier, the National Commission on Urbanisation had recommended that in the urban areas, the objective should be to have a provision of at least 70 litres of water per capita per day for domestic requirements. KMC’s Basic Development Plan for Kolkata, released in 1966, recommended a provision of 272 litres per capita per day in Kolkata and Howrah municipal areas and 217 litres per capita per day for the rest of the metropolitan district. The municipal corporation presently supplies about 750-800 million litres per day (MLD) from its surface water sources and 136 MLD from groundwater sources. Additionally, it also supplies 300 MLD of unfiltered, but chlorinated water. KMC now claims to supply over 250 litres of water per day to residents in its jurisdiction. In other words, at least on paper, there is no shortfall even after taking into account the increase in population since 1981. But the stats don’t add up… KMC’s statistical figures, however, conveniently cover up the hardships that most residents face due to inequitable distribution. Moreover, at least 25-35 per cent of the water supplied goes waste due to leakages in the worn-out pipes, public taps and stand posts. Kolkata has some 8,000 stand posts in all and about 60 per cent of the water that these outlets supply is wasted (see picture). Yet, there is no alternative, as these stand posts are the only source of water for the poor. ts supply ty’s poor The rather high per capita water supply figure needs to be considered from another angle also. About 40-50 per cent of the total population in Kolkata lives in slums or squatter colonies and has to collect water from stand posts only. Another 20-25 per cent is served by single tap connections in their houses. Thus, the actual figure is unlikely to go beyond 60-80 litres per day. It is evident that a large volume of water is being wasted due to improper management. Considering the extremely poor level of water supply in majority of municipalities and non-municipal urban areas in the Kolkata Metropolitan Development Authority areas outside KMC, the approach appears to be lop-sided. History of water supply in Kolkata Potable water supply began in Kolkata in 1869 with the installation of a slow sand filtration unit having a capacity of 6 million gallons per day (mgd) at Palta. The plant’s capacity was raised, in stages, to 32 mgd by 1911. The city expanded rapidly between 1948 and 1966 and had to cater to a huge influx of people for various reasons, including the Second World War, the infamous Bengal famine, Independence and partition of Bengal. Large settlements grew on both side of River Hooghly in the Gangetic delta. The Kolkata Municipal Authority (KMA) looked after the civic needs of a population of more than 14.6 million, settled over 178,500 hectares. The first water works at Palta for supply of 27.28 million litres of filtered water every day to a population of 0.4 million was constructed in 1870 for a community water supply scheme with a supply of 68 litres per capita per day. Today, the Palta Water Works, which is situated on 195 hectares along the riverfront, supplies about 780 million litres of water every day on an average. The water from Palta flows through four pipes (of 1 to 1.8 m in diameter) to the reservoirs and pumping station at Tallah. From Tallah the water is distributed to the city by four zonal mains, which feed the vast distribution network measuring about 3,800 kilometres in length. However, the Tallah-Palta water supply system is not enough to serve the consumers in the southern parts of the city, particularly in areas that have been recently added to the Kolkata Municipal Corporation like Tollygunj, Garden Reach, South Suburban and Jadavpur. Considering the low pressure and inadequate supply in these areas, supplementary arrangement from local groundwater sources is made to augment the supply. With the setting up of Garden Reach works in 1982 to supply water to these areas, the critical water supply distribution system in South Kolkata is expected to improve. Presently, Garden Reach supplies 50 million litres per day, which is expected to rise to 217 million litres per day when the construction of various units of the water works is completed. Present status According to B K Maiti, Deputy Chief Engineer, Water Supply Dept, KMC, the demand as on 2004 is around 334 million gallons per day (MGD) and supply from surface and groundwater source is about 320 MGD with a gap of 10 MGD. In 2002, KMC supplied 1062.18 MLD of water, falling short of the demand by almost 189 MLD. However, in 2003, the average supply rose to 1262.52 MLD, meeting nearly 90 per cent of the requirement. Keeping the needs of the growing population in mind, KMC has undertaken several capacity enhancement and upgradation programmes and hopes to exceed the demand by 2005. The New Palta Water Works at Indira Gandhi Water Treatment Plant is a notable step in this process. The 378 MLD water generation project, which was commissioned in July 2004, further augments Palta’s capacity by 226.8 MLD. This, along with the increased supply from Garden Reach Water Works, will increase the per capita water supply to 234 litres per day from the present 202 litres per day. Kolkata’s water supply at a glance: Total daily potable water supply (in million litres) 1350 Per capita availability of water per day (in litres) 202 No. of tubewells Big diameter Small diameter 455 7875 No. of connections Domestic Industrial and commercial 2,12,000 25,000 Public Access Stand posts (in numbers) Street hydrants that use unfiltered water (in numbers) 17,019 2,000 No. of reservoirs 7 Present 14 Under construction 96 Combined capacity (in million gallon) After the commissioning of the New Palta Water Works, the per capita water availability in Kolkata will be 234 litres per day Source: KMC Problems that Palta Water Works faced Rapid growth of population in the city placed a huge burden on the plant. Increased salinity in River Hooghly, excessive leakage through the old distribution network and loss of pressure head as water had to be conveyed over long distances were among the chief problems that the plant faced. But, with the construction of Garakka Barrage and diversion of sweet water to River Hooghly, there has been marked reduction in the salinity of river water. With the establishment of Kolkata Metropolitan Development Authority (KMDA), development work for improvement of surface water to KMC and other settlements in the Kolkata Metropolitan Area have been undertaken. The plant, which had an initial capacity of 22.68 million litres per day (MLD), generated filtered water through sedimentation in pre and final settling tanks and slow sand filtration in the Old Series of 12 filter beds. Another 24 beds, each with a capacity of 3.78 MLD, were added between 1888-1893. In 1905, filter beds with 7.56 MLD capacity, called New Series, was started. Between 1920 and 1936 when 17 beds of 11.34 MLD capacity and one bed of 7.56 MLD capacity, called Extension Series, were introduced. With an output of 491.4 MLD the plant seems to have perennial capacity to serve. In 1952, a 12-bed rapid gravity unit with a capacity of 75.6 MLD was added. This process helped in reducing the sedimentation time. In 1968, another 226.8 MLD rapid gravity filtration unit was added. Slow sand filter The slow sand filtration system is an effective and reliable system that does not require daily washing. A single bed can work up to 100 to 200 days. Formation of a biological mat soon after effective charging removes turbidity, colour and microbes. The biological mat on the surface removes 95 per cent of the colloidal clay particles, which are hideouts for microbes. The process requires much less chlorine to disinfect water. Regular scrapping of about 10 to 20 millimetres of the top sand layer once in every 100 days keeps the beds ready for reuse. Water supply in suburbs The standard of services and quantity of supply in the municipal and non-municipal urban areas outside KMC compares very poorly with that in the city area. Whereas the basic development plan envisaged a supply of 227 litre per capita day with the average rate of supply being only 56 litre per capita per day with the average rate of supply being only 56 litres per capita per day. In 1981, the total water demand of two municipal corporations and 33 municipalities of the Kolkata Urban Agglomeration was 1532 MLD. By 2001, it rose to 2386 MLD. The gap between the existing supply and demand is considerable. The organisation’s capacity and infrastructure of the municipality outside KMC are so poor that the existing supply in most of these municipalities is only a fraction of the optimum possible supply from the installed capacities of water supply systems in those municipalities. In the non-municipal urban areas, there is no organised public water supply system whatsoever. Distribution system The most critical aspect of Kolkata’s community water supply is the state of its distribution system. The number of zonal mains is inadequate and the greater part of the network has long outlived its natural life and is in an advanced stage of dilapidation. Major and minor tank leaks are endemic and bursting of major pipes is frequent. These factors are the principal causes of not only substantial loss of water in transit but also gross pollution and deterioration in water quality. Construction of Metro railway and other public utility services has damaged and aggravated the decaying water distribution system in the city. Water charges According to KMC the production cost for 1000 litre of water is about Rs 3.11 and the selling cost is Rs 3 for domestic purposes as on 2003. The Kolkata Municipal Corporation Act, 1980, empowers the corporation to impose fees at such rates as would be determined by the regulations made in this regard for supply of water to premises for domestic purposes. The KMC decision to impose water fees on 27.31 per cent of the 152,578 holdings in the city as on 31.08.85 is encouraging. This fee at present is charged on holdings, whose annual valuation is above Rs 2990, so that the economically weaker section are exempted from paying the tax. KMC to collect water tax After withdrawal of subsidy on water supply in Kolkata, the citizens collectively may have to pay about Rs 600 million annually to the civic authorities. Under directions of the Asian Development Bank (ADB), KMC will levy charges for water supply, sewerage and drainage charges to recover costs. Water supply in the city is subsidised under the current system. In 2001-02, Rs 757.1 million was spent in generation and supply of filtered water in KMC areas, while only Rs 183 million was recovered as water charges. The KMC supplies an average of 250 MGD to the city, at a cost of Rs 10 per kilolitre. The supply works out to an average of 45 litres per head per day. Presently, the water charge is based on the size of the ferrule in a house – homes half-inch ferrules are charged Rs 480 per year (to go up to Rs 600) and one-inch ferrule connections at the rate of Rs 790 (to go to Rs 1,000). For bulk users of water, consuming over 1000 kilolitres per day, water meters are installed. Metered water supply is to be charged at the rate of Rs 3 per kilolitre for domestic consumers, while industrial and commercial connections are to cost Rs 15 per kilolitre. According to a survey, this would generate a surplus of Rs 700- 800 million per year. For sewerage and drainage, a 50 per cent surcharge will be imposed on water tariff for domestic consumers, which will be 80 per cent for industrial consumers. ‘In addition, 15 per cent of the consolidate rate charge will be allocated for supporting water supply, 15 per cent of sewerage and drainage and 15 per cent of SWM,’ the ADB report stated. (The Times of India, November 26, 2002) Water quality and health risks The city has been notorious for the epidemics of cholera and other water-borne diseases for long. A newspaper report published on September 29, 1825 states: ‘…the terrible way in which Cholera has broken out in Kolkata is beyond all description… it is very difficult to ascertain the number of people that are dying every day in Kolkata, we have heard that in the week the average number of deaths may be 400. It would be no exaggeration but on the side of under estimation.’ The incidence of cholera rose sharply with the increasing population of the city in the late 1940s and 1950s due to influx of refugees. In 1958, there were 4,895 cases of cholera and 1,756 deaths were reported. Though the city now witnesses fewer cholera epidemics, during the 1970s and 1980s, the city witnessed outbreaks of gastroenteritis, hepatitis, dysentery and other water borne diseases. Experts believe that though the water supply from Palta is safe after the treatment it undergoes, it gets contaminated as it passes through the underground distribution network. The fear of water-borne disease striking is the greatest during the monsoons. The floods increase the chances of surface water being contaminated by sewage and garbage washings. The contaminated water then enters the distribution system through breaches in the distribution network. Special mention may be made here of the unfiltered water supply of 340 MLD drawn from the river and distribution through 1,120 kilometres of mains, meant chiefly for fire fighting, street washing, water closet flushing, etc. The city’s poor also use this untreated water for domestic uses. It was a major factor behind the cholera epidemics that afflicted Kolkata till 1960s. Chlorination of unfiltered water on the basis of a report submitted by the All India Institute of Hygiene & Public Health has dramatically reduced the cases from 1963 onwards. A survey, conducted by the Federation of Consumers Association (FCA), West Bengal and Better Business Bureau, a NGO found that 80 per cent of the 1,000 water samples collected from all municipal wards of the city contain E.coli (bacteria that indicates the presence of faecal matter), Salmonella (responsible for typhoid), Shigella (bacteria that causes dysentery) and Vibrio (causes cholera). The scenario is the worst in the Kasba-Ballygunj area. Though chlorinating the water could have killed these microbes, not the slightest trace of Chlorine was found even in a single sample. (Source: The Telegraph, April 14, 2003) Drinking water quality in Kolkata9 A recent study conducted by Better Business Bureau (BBB) concluded that the quality of water supplied by KMC is good at the source (where it is treated and pumped from), but gets contaminated on its way before it reaches the consumers. The researchers examined 100 samples out of a total of 1000 samples collected from nine zones. The study revealed: 87 per cent of water reservoirs serving residential buildings had high traces of human waste Water collected from 63 per cent of taps showed a high level of faecal contamination, while 20 per cent of water samples collected from the city's hospitals were also polluted. Roughly one-fifth of the deep wells and hand pumps maintained by the Kolkata Municipal Corporation also had traces of excrement. The zone-wise analysis is as below: Zone-wise analysis of water samples Zone Areas included no Zone 1 Extends from Lake Market in North to Garia in South, Raja S.C.Mallick Rd. in East to Deshpran Sasmal Rd. in West. Zone 2 Extends from Taratal - Majerhut in the North to Biren Roy Road.- Barisha in South & Banamali Laskar Rs. - Behala in the West to Deshpran Sasmal Rd. in the East. Zone 3 Zone 4 Zone 5 Zone 6 Zone 7 Zone 8 Extends from Kasba - Ballygaunge in the North to Garia in the South, E.M. Bypass in the East upto Raja S.C.Mallik Road, Garihat crossing & NSC Bose Road S.C. Mallick Rd. in the West. The zone is bounded by Circus Avenue Park Circus - Tapsia Rd. in the North and Despriya Park - Ballygaunge in the South, E.M. Bypass in the East and S.P. Mukherjee Rd. in the West. The zone is bounded by Lenin Sarani, Cannel South Road in the North, A.J.C, Bose Road ... Tapsia Rd. in the South, Maidan in the West to Dhapa ... E.M.Bypass in the East. The zone is bounded by Belghachia Rd. , Pati Pukur , Lake Town in the north to Sealdah , Beliaghata Road in the South , A.P.C. Road in the West to Nazrul Isam Sarani , Ultadanga Road , National Medical College in the East, Tala in the South , Hoogly River in the West and Seth Bagan .. Dum Dum Road in the East. The zone is bounded by Shyam Bazar Crossing of Belghachiya road in the north to Lenin Sarani in the South , Strand Road, Barabazar in the West and Acharya P.C. Road in the East. Bounded by Sithi K.C. Roy road in the north, Belgachiya, Tala in the South, Hoogly in the West and Seth Bagan Dum Dum road in the East. Test result of groundwater samples Arsenic closes to permissible limit Arsenic closes to permissible limit Turbidity, TDS and iron were present in higher than permissible limits. Arsenic closes to permissible limit Turbidity, TDS and iron were present in higher than permissible limits. In Zone 5 and 6 both KMC and private bore wells were found to be totally free from any chemical contamination. Test result of KMC pipe water supply. 50 per cent of samples have high hardness and iron content. 3 per cent of samples displayed Arsenic higher than acceptable limit. Here groundwater also Arsenic, hence there might be contamination. Free from chemical contamination. Turbidity, Hardness and iron are above permissible limit in 2 per cent to 20 per cent of the samples. Free from chemical contamination. Free from chemical contamination. Free from chemical contamination. Turbidity, Hardness and iron are above permissible limit in 2 per cent to 20 per cent of the samples. Zone 9 The zone extends from eastern bank of Hoogly, Strand road (north) to Taratala road, Garden Reach (south), Taratala Road (west) to Despran Sasmal road (east) Turbidity, TDS and iron were present in higher than permissible limits. Turbidity, Hardness and iron are above permissible limit in 2 per cent to 20 per cent of the samples. Source: Better Business Bureau Arsenic in Kolkata The civic authorities have sealed the deep tubewells at Victoria Memorial Hall after all the test reports from the laboratories of the School of Tropical Medicine, Kolkata Municipal Corporation (KMC) and the Department of Public Health Engineers confirmed arsenic contamination beyond permissible limits. The concentration of arsenic was found to be four times higher than WHO prescribed benchmark. The KMC has made alternative arrangements to supply safe water to Victoria. (Source: The Telegraph, August, 1, 2003) GROUNDWATER SCENARIO IN KOLKATA History of groundwater extraction 10 The first move to tap sub-surface water in Kolkata was made as early as 1804. Between 1918 and 1940, nearly 200 medium diameter tubewells with an average yield of 27,275 litres per hour were set up in what is known today as Kokata Metorpolitan District. Many more tubewells were drilled during the World War II to ensure water supply during emergency. The population growth after partition made it necessary to install heavy-duty tubewells to supplement TallahPalta water supply, particularly in southern Kolkata. Though initially conceived as an emergency and stopgap measure, the system has now come to stay for good. Presently, Kolkata Municipal Corporation runs 455 large diameter deep tubewells and 7825 small diameter tubewells contributing about 136 million litres of water per day. An unaccounted number of deep tubewells by private industries and business establishments, housing estates and highrise apartment blocks have also been functioning. There are also several thousand small diameter tubewells owned by private households. Groundwater resource Due to large-scale withdrawal of groundwater from the confined aquifers, a depression of piezometric surface in Central and South Central Kolkata has developed. The magnitude of the depression is 6-8 metres, and has developed over a period of about 40 years (1958-98) in the core sector covering Narkeldanga- Park Circus – Bhowanipur. As a result, the general southerly flow in the confined aquifers has become radial in a much larger area surrounding the cone of depression. The central part of Kolkata Municipal Corporation area is drawing water from all directions resulting in its radial flow. The total quantity entering form the immediate vicinity of KMC area into the central depression zone comes to 204 MLD in the absence of precise Census data of the withdrawal structures it is difficult to evaluate precise ground water draft in KMC area. Groundwater withdrawal status as on 1988 Source Numbers Average discharge Larger diameter tubewells 325 Small private tubewells (4.5 inch diameter) 4834 68 cubic metres per hour 27 cubic metres per hour Assumed hours of pumping 7 hours Total per day withdrawal 153 MLD 7 hours 914 MLD Shallow hand pumps 12,000 0.68 cubic metres Total Source: Central Ground Water Board (CGWB) 7 hours 56.7 MLD 1123.70 MLD According to the Central Ground Water Board (CGWB) the withdrawal is 1123.70 MLD but the inflow is only 204 MLD, which results in the fall in the piezometric head. In 2003-04 according to KMC the number of larger diameter tubewells has increased to 455, and smaller diameter borewells to 9875 and the number of shallow hand pumps is 17,019. Hence the current groundwater based on the withdrawal figure by CGWB will be about 2120.5 MLD. Hence it is clear that between 1998 and 2003 the groundwater extraction has increased by 1.9 times in five years period. Groundwater quality (CGWB) The chemical quality of groundwater in the Kolkata area in the depth range of 60-250 mbgl is depicted through isochloride and isoconductance maps (based on the data for the April 1999 to understand the nature of chemical characteristics of groundwater. From the isochloride contour map it is seen that in the extreme northern part (North of Shyambazar area) chloride concentration in groundwater is above 500 mg/l. Similarly in the western part of Alipur i.e. in Garden Reach and adjacent area, the chloride concentration in groundwater is above 500 mg/l. In the area lying between Belgachia and Park Street, chloride concentration in groundwater is between 250 and 500 mg/l. In Garia-Jadavpur sector, chloride concentration in groundwater is within 250 mg/l. From isoconductance map, it is seen that extreme northern part of KMC area isoconductance value is above 2000 micro siemen/ cm at 250 C. In Sealdah-Beleghata-Narkeldanaga area and Garia-Putiari-Behala area in conductance value is between 1000-1500 micro siemen/ cm at 250 C. In Garden Reach area, isoconductance value is more than 1000 micro siemen/cm chemical character. Tanneries situated in the eastern part of Kolkata (Tangra, Tiljala, Tapsia, etc.) are a cause for concern as industrial effluents from these units pollute the Bheris, wetlands and agricultural fields. Toxic trace elements like, Chromium and Cobalt are found (above 0.01 mg/l) in the shallow aquifer (within 20 m bgl) in the area, which is not suitable for drinking purposes. However analysis of water samples from deeper aquifer (80 to 200m depth) shows that concentration of chromium, cobalt and other heavy metals is below permissible limit. Hydro-geological consequences of unplanned groundwater extraction 2 The impact of groundwater exploitation needs closer examination. Tests reveal that northern parts of Kolkata Metropolitan District have much greater value of groundwater transmissivity. Yet, it is southern Kolkata that is most reliant on groundwater sources. This lower availability and greater exploitation of groundwater produces consequences reflected in a number of surveys relating to the level of piezometric surface. A survey conducted in 1956 showed the depth of piezometric surface in the post-monsoon period descending from 4.27 metres in the northern suburbs to 5.46 metres in the southern city area. A much wider survey in 1985 showed the piezometric surface to be only 1.78 to 2.65 metres in the far north and 11 to 13.38 metres in the south-central area. By collating the results of two surveys, a progressive decline in the groundwater levels towards the south can be seen. This clearly indicates that the southern part of KMD has a much lower potential for groundwater exploitation. More crucial, however, is the overall decline in such water levels all over the KMD. At any given point, 1985 level was markedly lower than the 1956, the extent varying from 3.84 meters to 9.75 meters. This decline has obviously been caused by reckless and unplanned exploitation of groundwater resources during the last three decades. This can lead to gradual subsistence in land in the deltaic area as has been seen in Texas, Bangkok and some cities in China. As has been pointed out in the Basic Development plan, the poor quality of groundwater should also be taken into account in developing any rational plan of water resource management for the Kolkata Metropolitan District especially in the eastern and southern parts. Drainage and sewerage Kolkata has been plagued by severe problems of drainage due to its geographical location. The city has been notorious for water logging during the rainy months ever since it was founded. Situated between the tidal river Hooghly on the west and surrounded by swamps and marshes on the east and south, the city has suffered chronic drainage congestion during the monsoons, when the Hooghly River, the tidal creek, and the swamps over flow. Lack of drainage and the resulting unhealthy conditions particularly during the hot and humid monsoon moths makes the city’s environment appalling. The situation was so bad during the early years that a large number of people succumbed during the rains, every year, throughout the eighteenth century. This state of affairs continued upto the middle of 19 th century when efforts were initiated to improve the drainage. The drainage systems of the city have been designed as a combined system for the disposal of storm water as well as sewage and dry weather flow. The core of the system had been proposed in 1855 and constructed during 1860-1875 to cover originally an area of 1920 hectares. Subsequent modifications and augmentations during 1891-1906 brought another 3200 hectares in the newer southern areas of the city under the sewerage system. The sewage from the combined drainage system flowed into the creek of the tidal river, Vidyadhari, on the east of the city. Burdened with the entire city’s drainage system River Vidyadhari began to show signs of rapid deterioration. In 1943, a new scheme for both the outfall and the internal drainage system was commissioned. Since then, the system has undergone major modifications and expansion to meet the city’s rapid growth. The Masterplan prepared by the WHO for the Kolkata Metropolitan District in the 1960s dealt with these issues and has provided the guiding framework since then. Geographical and hydrological factors Kolkata’s drainage problem is aggravated by the topography (west to east- away from River Hooghly) and the tidal nature of the rivers and streams around it. The premature reclamation, which interrupted the natural land building process, resulted in the general ground elevation, which is lower that the high water level in Hooghly. Discharge of drainage, therefore would require constructing deep underground drains and pumping out the waste water at very high capacity and recurring costs. The tidal rise of water level in the water bodies (3 metres during winter and 5 meters during monsoon) imposes yet another constraint on the speedy and effective disposal of Kolkata’s drainage. Water bodies of Kolkata Water bodies of Kolkata requires urgent management initiatives, says Mohit Ray of Vasundhara3, NGO that works for wetland development. According to Ray, the water bodies are water resources for poor people. Hence, efforts to improve people’s quality of life must include a plan to use these water bodies wisely. The encroachment and filling of water bodies in the urban areas are taking place because of lack of planning, information and management. There is no database on these 3,000 water bodies, which serve about 400,000 people. There are no studies on management issues of urban and peri-urban water bodies, which are considered as a special group of natural resources. Kolkata Municipal Corporation does not have any specific section to deal with these water bodies. Conservation efforts for these water bodies become useless if there is no programme for its future preservation. Kolkata needs a special institution for proper management of these urban water resources. Kolkata still has about 3,000 ponds, which provide about 15 per cent of water requirement of the city but no city planning exercise has ever mentioned these important water resources. Vasundhara has been working to spread awareness through direct participation and research for last several years. Inadequate treatment capacity It is to be regretted that Kolkata does not yet have a full-fledged sewage treatment plant. There is only a primary treatment plant at Bantala to treat a part of the sewage. It contains two sediments tanks, each containing two sedimentation tanks, each having a capacity of 273 million litres per day, two sludge pumphouse and 12 sludge lagoons. Even this plant has ceased to function. It needs to be recommissioned urgently and placed under the Kolkata Municipal Corporation. At present, it is being operated by the irrigation and waterways directorate. Sewage-fed aquaculture in wetlands Kolkata has a unique system for the utilisation of sewage in the eastern suburbs of the city. For a long time now, the vast wetland there has supported sewage fed fisheries, which supply a considerable quantity of fish to the Kolkata market. Sewage irrigation is also practiced to produce vegetables for bulk supply to the city. According to Dhrubajyoti Ghosh, the wetland produces 10,000 tonnes of fresh and relatively cheaper fish and 147 tonnes of vegetables daily. Bonani Kakkar of PUBLIC, a local NGO, says, “Since the wetland is near to Kolkata, the vegetables and fish are available at a cheaper rate, due to less transportation cost.” The wetlands in Kolkata originated largely from the inter-distributory marshes, created by the shifting of the main river, Hooghly. It is estimated that out of 10,120 hectares of wetland existing in 1945, an area of about 4700 hectares of land were used for sewage fed fisheries that yielded an average of 8.40 quintals per hectare. By 1985, the wetland area under sewage fed fisheries has declined to 3,200 hectare. The domestic sewage generated by the city, estimated to be 1394.42 MLD, gets partly purified as it flows through the east Kolkata wetlands by means of a system of principal and ancillary channels. These flows are utilised in sewage-fed fisheries having an average production of about 3.44 MT/ hectares/year and vegetable production. At present about 3898.27 hectares (out of this 697.72 hectares are seasonal) are covered with sewage-fed fisheries. There are about 58 fisheries in east Kolkata wetland area, providing direct employment to 15,700 people and indirect employment to 23,600. The employment generation is for the population living below the poverty line. The fish are marketed through different auction markets. Chingrighata market is the most important one with an average daily sale of 12.6 metric tonnes. East Kolkata wetland The East Kolkata wetlands is an urban facility that treats the city’s huge wastewater and utilises the treated water for pisciculture and agriculture, through recovery of wastewater nutrients in an efficient manner. Here, wastewater is used in fisheries and agriculture covering about 12,500 hectares that has been designated as conservation area by an order of the Kolkata high court. The conservation area, also described as the waste recycling region, has three major sub-regions of economic activity – fishponds (bheris), garbage farms and paddy lands. The smallest recycling sub-region on the edge of the city covers the vegetable fields that grow vegetables on a garbage substrate and are uniquely planned with alternate bands of garbage filled lands and elongated trench-like ponds locally known as jheels. Sewage is detained in these jheels for sometime, after which the treated effluent is used for irrigating the garbage fields for growing vegetables. In the fishponds, the city’s wastewater is made to flow through a network of drainage channels. The wastewater fishponds act as solar reactors and complete most of their biochemical reactions with the help of solar energy. Reduction of BOD (biochemical oxygen demand) takes place due to the unique phenomenon of algae-bacteria symbiosis where energy is drawn from algal photosynthesis. In this way, requirement and consumption of energy remains the minimum. Unlike conventional mechanical sewage treatment plants, wastewater ponds can ensure efficient removal of coliforms that are prone to be pathogenic (Turning Around, 1996). The fishponds drain out the used water to irrigate paddy fields. The fishpond ecosystem of east Kolkata is one of the rare examples of environmental protection and development management where the fish producers and farmers have adopted a complex ecological process for mastering the resource recovery activities. What is remarkable is that the fish yield rate attained is among the best in any freshwater pisciculture in the country. The east Kolkata wetland has the largest number of sewage-fed fishponds in the world that are located in one place. The knowledge that has emerged based on traditional skill, enterprise and innovation provides an alternative to the conventional option of wastewater treatment by an ecologically sustainable and wise use of wetlands. Here the task of reusing nutrients is linked with the enhancement of food security and development of livelihood of the local community using nutrient rich effluent in fisheries and agriculture. The conventional sewage treatment plant is considered an externality in the basic social and economic of Kolkata and its fringe. Interestingly, a large part of this ‘folk’ technology is part of an oral tradition. New generation environmentfriendly engineering has been quick to incorporate the advantages of natural biological processes and principles of ecological regulation. In this context, using wetland functions for reducing wastewater pollution and reuse of nutrients is an example of an effort that has opened new areas of research and application in other parts of the world too. In 1980, on an initiative of the Government of West Bengal, the wetland area and its reuse practices were assessed. By 1983, the first scientific document on this ecosystem was published which enabled the rest of the world to know about the ecological significance of this outstanding wetland area. In 1985, the map of the waste recycling region that forms the basis of all planning and development activities on this wetland area was prepared. In the same year, the state government put forward a proposal to introduce a resource efficient stabilisation tank (REST) system for the treatment and reuse of city sewage. The Ganga Project Directorate as an alternative to conventional energy expensive and capital-intensive mechanical treatment plants accepted this. A number of such projects under the Ganga Action Plan have now been completed and are working. Towards the end of the eighties real estate interest reached a new high and there was a strong tendency to convert water bodies and wetlands into housing complexes. To combat this, the Government of West Bengal initiated a number of development control measures. For a comprehensive planning and development of the entire region, a baseline document for management action plan using Ramsar guidelines has been completed. Industrial pollution in wetland A large number of small and medium scale industries are availing of the drainage system laid by municipality since last couple of decades to release their untreated effluent. These drainage channels are linked with the main outfall channels leading to the river Kulti. This industrial wastewater can cause undesirable impact on the fish and vegetables grown using the same. It is imperative to identify such industrial units which discharge contaminated effluent to bring them under the purview of pollution control regulations. Common in-situ effluent treatment plants for the polluting industries are considered to be the likely solution to this emerging problem. Quality of wetland3 The report on Environmental scenario of sewage fed fisheries of Kolkata, contains the results obtained from analysis of the inlet and settled water of Captain Bhery, which was collected by the Fisheries Department fortnightly throughout the year. The pathogenic bacterial count was found to be much less in settled water compared with inlet water. Sewage outflow from Chowbhaga pumping station11 The BOD in the raw sewage has been found to vary between 30-116 mg/l while the same in the settled ponds is as low as 2.1 –5.7 mg/l. COD also drastically fell from a concentration of 150-180 mg/l to 84-97 mg/l. DO increased from 0.8 mg/l in the raw sewage to 3-12 mg/l in the settled ponds. pH at inlet points varied from 7.2 –8.2, but at the growing pond it was between 8.7 – 9.5. Ammonical nitrogen and nitrate nitrogen concentrations in the inlet were 0.107 –0.32 and 0.52 –0.8 mg/l respectively while the same in the settled ponds were 0.001 – 0.005 and 0.102 – 0.42 mg/l respectively. Bioaccumulation of heavy metals in the sewage fed system was confirmed. Among the heavy metals, zinc seems to be the dominant one with its concentration in the inlet being 0.9 mg/l, followed by lead (0.6 mg/l), copper ( 0.2 mg/l), chromium ( 0.15 mg/l) and cadmium ( 0.02 mg/l). However, presence of heavy metal in fish tissues was found to be insignificant. In spite of that, it has been suggested that instead of allowing the raw wastewater to directly enter the fish ponds, as is sometimes done, it should pass through a water hyacinth tank where some amount of heavy metals may be observed. Regarding disease and parasites the, bhery fish are practically free from any major disease. Rainwater harvesting in Kolkata Rainwater harvesting will be an ideal option to prevent the alarming fall in the water level in the city. The study of the rainfall pattern and sub surface geology shows that both storage and recharge methods can be successful applied in the city. Rainfall pattern in Kolkata The city lies in a monsoon region, with most of its average annual rainfall of 1500 mm falling from June through September. Though winters are mild, with an average January temperature of 19° C (67° F), the temperature sometimes dips to 10° C (50° F). From March through September, Kolkata is hot and humid, with an average July temperature of 29° C (85° F); in the months of May and June the temperature may rise as high as 38° C (100° F). Water harvesting potential of the city Kolkata Municipal Area = 187 sq km Annual average rainfall = 1500 mm Total rainwater falling over the city = 187 x 1,000,000 x 1500 = 280,500,000,000 litres = 768 MLD Present water supply = 1209.6 MLD Even if we assume 70 per cent of the area to be developed, 50 per cent of it to be roofed and we collect 70 per cent of the water falling over it, the quantity of rainwater that can be harvested works out to 188 MLD. This is a sizeable quantity compared to current water supply. How much water can be harvested from individual houses If a house in Kolkata has a rooftop area of 100 sq m, one can harvest about 1,20,000 litres of water. The formula for calculating the amount of rainwater that can be harvested is as follows. Runoff =A x R x C A=Area R=Rainfall in millimetres C=Runoff coefficient (0.8) Here’s how: Area (A)=100 m2 Rainfall = 1500 millimetres Runoff coefficient = 0.8 Runoff (100 x 1500 x 0.8) = 1,20,000 litres Storing rainwater The design parameter for storage depends on the number of dry days and requirement. The details for calculation an optimum storage tank is given below. Rainy days in the city The above graph shows that the number of dry spell or non-rainy days in a year is 200. So, we have to design the size of our storage tank in such a way that during the dry periods, water is available for drinking purpose. The below mentioned calculation can be applied to determine the size of the storage tank. No. of persons in a household No. of dry days in a year Per capita consumption (lpcd) Average annual rainfall (mm) Rooftop area (sqm) Runoff coefficient Size of the storage tank : : : 10 : 200 6 : 1500 : 20 : 0.80 10 x 200 x 6 = 12,000 litres Check : Water available from rooftop : 1500 x 20 x 0.8 = 24,000 Hence, sufficient water is available to meet the demand of 12,000 litres The storage tank can be ferrocement tank, plastic tank or brickwork tank. The tanks can be placed of surface or below the ground level also. Case study Recharging in Kolkata Recharging is also viable in Kolkata, but for recharging the under ground aquifers, knowledge of Hydrogeolgy of the city is essential. Hydrogeology of Kolkata2 A succession of quaternary sediments comprising clay, silt, fine to coarse sand and occasional gravel lie underneath Kolkata. Below these sediments at depths beyond 296 m, there is a thick sequence of Pliocene clay at least down to a depth of 614 m below the land surface. The thickness of the top clay bed varies from place to place with an average thickness of around 40 m. The maximum thickness of over 80m of this bed is encountered at Beleghata. The clay bed thins out to about 20m towards east of Kolkata. In the central part of the city, the thickness of the top clay bed is over 50m. Occurrence of groundwater is Kolkata is controlled by this geological set up. An aquiclude represented by clay and silty clay with an average thickness of 40m occurs in the upper part of the sedimentary sequence prevents natural recharge. Where to divert the rainwater in North Kolkata and Howrah2 Sl No. Location Sub-surface geology in meters below ground level (mbgl) Depth of the recharge well in mbgl 1 Akra Road 0-24 clay 50m 24 –32 fine sand 32- 48 clay 48- 104 coarse sand 2 Garden Reach 0-56 clay 60m below 56 coarse sand 3 Hastings 0-32 m fine sand 32 – 56 m clay Shallow recharge structures up to 32m and deeper structures below 60 m below 56 m coarse sand 4 Park Street 0-48 clay 50 Below 48 fine and coarse sand 5 Seal Lane 0-40 clay 40 below 40 fine and coarse sand 6 Subhas Sorovar 0- 56 clay 60 below 56 find and coarse sand 7 8 Bagmari park Manicktala 0-40 m clay Baksara 0-32 clay 45 Below 40 fine and coarse sand 35 below 32 fine and coarse sand 9 Tikiapara 0-48 clay 50 below 48 fine and coarse sand 10 Sovabazar 0- 56 clay below 56 sand 60 Where to divert the rainwater in South Kolkata 2 Sl No. Location Sub surface geology in meters below ground level (mbgl) Depth of the recharge well in mbgl 1 Alipur 0-24 clay 25 below 24 fine and coarse sand 2 3 4 Lansdown Road 0-48 clay Mandivilla Garden 0-56 m Barisha 0-40 clay 50 below 48 coarse sand below 56 coarse sand 45 40 – 120 sand below 120 clay 5 K P Roy Road 0-8 clay 8- 48 fine sand Shallow structures to depth of 15m and deeper structure to a depth of 60m 48 – 56 clay below 56 coarse sand 6 Ashok Nagar 0- 32 fine sand 32 - 72 clay Shallow structures upto a depth of 15m and deeper structures to a depth of 75m below 72 fine and coarse sand 7 Jadavpur 0-16 clay 16- 32 fine sand Shallow structures to depth of 20m and deeper structures to a depth of 40 32 – 36 clay below 36 fine and coarse sand 8 Dhakuria 0-16 clay 16-40 fine sand Shallow structures at 20m and deeper structures for a depth of 40m below 40 coarse sand 9 Jodhpur Park 0-48 clay Deeper structures upto a depth of 50m below 48 coarse sand 10 Tiljaya 0-32 clay 35m below 32 m coarse sand Case studies I. Bidhan nagar Government College, Salt Lake. Case Background The college, which is of 7.5 acres (30,000 sq m), is located in Salt Lake. The daily water requirement is fulfilled by municipal supply and from its own tubewell. Measures taken for rainwater harvesting Part of the rooftop rainwater is diverted to storage tank of 12,000 litres capacity (see site plan). The approximate cost for constructing the ferrocement tank was about Rs 30,000. The project was implemented in January 2004 and West Bengal Pollution Control Board funded the project. Rooftop rainwater harvesting I. Storing rainwater The rainwater generated at a rooftop area of about 50 sqm from a total rooftop area of 2,000 sqm is harvested. The rooftop rainwater flow to the storage tank through the down takes pipe of 6-inch diameter. The filtering tank provided in the top of the storage tank filters the silt from the rooftop. The stored water is utilised for non-potable purposes like gardening and washing purposes. The cross section view of the storage tank is given below. II. All India Soil and Land Use Survey ( AISLUS), Patuli- Baishanabghata. Case Background This is the first rainwater harvesting project of Kolkata at AISLUS complex. The project was funded by CGWB, designed and implemented by Ardem Centre for Resource Development and Environmental Management. The annual water harvesting potential of the site is about 811 cubic meters. Rainwater harvesting measures The rooftop rainwater from an area of 676 sq m is harvested through recharge well with two recharge borewells. The approximate cost for constructing the ferrocement tank was about Rs 5 lakh. The project was implemented in 2004. Rooftop rainwater harvesting I. Recharging groundwater The rainwater generated at a rooftop is collected in series of collection chamber. The collection chambers are interconnected by underground pipe and the water is finally diverted to the recharge well (see picture of recharge well). The well is 11.57 m in length, 1.65 m in width and 3 m in depth. The recharge well is provided with two recharge borewells of 150 mm diameter to a depth of 119 m. The recharge well is provided with gravel and sand for filtering purposes. References: 1. Wetlands of Kolkata (Source: Kolkata – The city of wetlands, Dept of Fisheries, Govt of W Bengal) 2. Groundwater in urban environment of India, CGWB, Faridabad, Dec 2000. 3. Annual survey of Environment, Vasundhara, 2004 4. Annual survey of Environment, Vasundhara, 2003 5. Dhrubanjoti Ghosh, Institute of wetland management and ecological Design. 6. Nisitendra Nath Som, Director, Physical planning Unit, KMDA 7. Kolkata Municipal Corporation 8. Annual reports 2001-2002, West Bengal Pollution Control Board. 9. Better Business Bureau, Kolkata. 10. Water of west Bengal: Souvenir 11. The city of wetlands- Edited by Madhumita Mukherjee , Department of Fisheries, Govt of West Bengal.