South Asian Women – Negotiating Identities SOUTH ASIAN

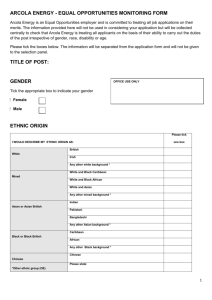

advertisement

South Asian Women – Negotiating Identities SOUTH ASIAN DISABLED WOMEN: NEGOTIATING IDENTITIES 2005 Dr. Yasmin Hussain Department of Sociology and Social Policy University of Leeds Leeds LS2 9JT Tel: 0113 233 4618 Email y.hussain@leeds.ac.uk Biographical Note Yasmin Hussain is a Research Fellow in the School of Sociology and Social Policy, University of Leeds. 1 South Asian Women – Negotiating Identities SOUTH ASIAN DISABLED WOMEN: NEGOTIATING IDENTITIES ABSTRACT This paper is concerned with the identities of disabled South Asian women within Britain. It presents empirical evidence concerning how disability, gender and ethnicity are negotiated simultaneously for young disabled Muslim and Sikh women. How these identities are negotiated is analysed in the realms of family, religion and marriage drawing on qualitative interviews with the young women, their parents and siblings. The paper argues against ideas of singular identity or the hierarchisation of identities or oppressions. The paper contributes to contemporary debates about how young South Asian women are constructing new forms of identity in Britain. 2 South Asian Women – Negotiating Identities SOUTH ASIAN DISABLED WOMEN: NEGOTIATING IDENTITIES INTRODUCTION This paper presents an analysis of disabled South Asian women within their respective ethnic, religious and cultural frameworks. Literature addressing ethnic minorities and disability has largely ignored the concerns of South Asians and especially South Asian women. Furthermore debates about identity, disability, ethnicity and gender take place in isolation from each other, yet they need to be considered in relation to each other. South Asian women – irrespective of impairment – may identify with different religious and cultural values to those of wider society (Modood et al., 1994). It is the convergence of multiple places and cultures that transforms the terms of South Asian women’s experiences, a process which requires them to negotiate and re-negotiate their identities. It is against this background that this article aims to decipher questions of identity, by examining young women’s experiences of the inter-connected practices of religion, family life and marriage within the South Asian community in Britain. These practices are the focus of the empirical analysis as they are the most significant sites of the hybridisation of identity, negotiation between parents and children and where questions of sexuality and the meanings ascribed to the disabled body come to the fore. The views of these women and those of their parents and siblings show how these experiences are socially constructed and regulated. Their place within society, the lives they lead, their relationship with others, and attitudes towards them, are part of a broader social and cultural picture. Their lives are shaped most immediately by cultural and religious factors largely through the family and the community. Ethnicity 3 South Asian Women – Negotiating Identities is an added dimension to the lives of the young women interviewed, as they relay an experience of disability in which they attempt to reconcile the inability of the wider society and of the minority community to accommodate their impairments. What is remarkable about these women is that irrespective of the boundaries they encounter they succeed in maintaining positive ethnic and religious identities. First the methodology of the research is outlined with a particular emphasis on how the sample was constructed in order to address the central research questions. This is followed by a discussion of recent debates around the relationships between disability, gender and ethnicity. This section aims to show how mainstream discussions of disability (e.g. Corker and French, 1999; Oliver, 1996; Swain et. al. 1993) and disability and gender (e.g. Lloyd, 2001; Morris, 1991) tend to ignore ethnicity, and how, when the ethnic dimension is introduced, many of the issues raised within the disability studies literature have to be re-thought and cannot be assumed to be universal. The rest of the paper is then concerned with the empirical data focussing on the inter-related questions of religion, family and marriage METHODOLOGY The data used in this research was carried out as part of a study entitled ‘Disability, Ethnicity and Young People funded by the Joseph Rowntree Foundation (Hussain et al, 2002). The project used qualitative methods and analysis, based on semi- structured interviews. Young people were interviewed as well as their parents and siblings where possible. The focus was on young disabled South Asian people who had been born or had grown up in Britain and who had recently or were currently going through significant life course transitions such as marriage. The inclusion of parents and siblings in the sample represented an important methodological principle, 4 South Asian Women – Negotiating Identities to ensure that disability did not dominate the respondents’ narratives. In-depth interviews with topic guides for all three groups of interviewees were used. Questions were framed around the following headings: social networks; family relationships; religion and language; living with a disability; society and disability; service support; education; and future expectations. Twenty-nine disabled young people were interviewed; sixteen young men and thirteen young women; between seventeen and thirty years old. Nineteen young people were Muslim and ten were Sikh. In addition to this fourteen parents were interviewed; eight described themselves as Muslim, six as Sikh. Fifteen brothers and sisters were also interviewed and who, where possible, were matched with the gender of their disabled sibling. Overall ten interviews were in Punjabi, one in Urdu, and forty-seven were in English. The interviews were tape recorded and transcribed and pseudonyms used to ensure the anonymity of respondents. Strenuous attempts were made to generate a Hindu sample through the same mechanisms as the Muslim and Sikh sample, both in the North of England and the Midlands. However this was unsuccessful; Hindu disabled young people were absent from the local authority registers and neither were they recognised by the Hindu community or religious organizations. Clearly this is a major limitation on this study in terms of making wider generalisations about South Asians and comparisons between them, and this experience suggests that a very different methodological approach to researching disability within the British Hindu community is needed. The sampling frames allowed us to approach individuals with a range of experiences and circumstances, in sufficient numbers to allow meaningful analysis. A range of ages, for example, was included, as well as a balance of young men and women. Although this paper focuses on the experiences and identities of young 5 South Asian Women – Negotiating Identities women, the inclusion of men in the sample allows some important comparisons to be made below at certain crucial points. It was decided to select people on the basis of religion because evidence suggests this is a more important variable than parents’ place of birth for South Asian ethnic identities in Britain (Modood et. al. 1997). The sample was generated from a diverse range of organisations. This would ensure it was not dominated by groups of individuals with similar experiences. The need to include people who were not in touch with state services, for instance, was recognised as important, as was the inclusion of individuals who were not necessarily active members of the voluntary sector. The young disabled peoples’ parents were largely working class, who were either unemployed, worked in textile factories or owned small businesses such as shops. All the parents were born either from India or Pakistan. The fathers sometimes stayed at home to help the wife look after a disabled child. Respondents had physical impairments – half of which had the impairment from birth, the others had acquired the impairment through illness or accidents. 6 South Asian Women – Negotiating Identities ETHNICITY, DISABILITY AND GENDER The medical model of disability, with its emphasis on individuality, rehabilitation and sense of personal tragedy, has been challenged by the social model emphasising that many of the disadvantages faced by disabled people arise because of the wider society’s inability to accommodate them (Corker and French, 1999; Oliver, 1996; Swain et al., 1993). This suggests that impairment can only be understood against what is considered as ‘normal’ for someone of their own age, gender and social class. Normalcy is not a given universal and impairment needs to be seen in its social and cultural context (Ahmad, 2000). Despite its valuable and important role in asserting the rights of disabled people, the disabled peoples’ movement has being criticised for not recognising ethnic diversity (Stuart, 1996). For many disabled ethnic minority people racism remains an issue and affects their engagement with the wider society. This is manifest, for instance, in the greater social and material inequalities experienced by South Asian families when compared to White families (Mason, 1999; Modood et al., 1997). Furthermore, South Asian families with a disabled child tend to be poorer than their White counterparts and have less access to services and benefits. The barriers faced by ethnic minority families with a disabled or chronically ill child act to exclude them from society (Chamba et al., 1999). This is part of the broader context within which disability assumes a specific meaning for South Asians. The failure to engage academically with the circumstances of those individuals who are both disabled and from ethnic minorities renders them invisible (Begum, 1992; 1996). Women’s writings on disability during the 1980’s and 1990’s had raised the question of the subordination of disabled women (Lloyd, 2001; Morris, 1991; Boylan, 1991). However, the category of ‘disabled woman’ failed to relate to ethnic minority 7 South Asian Women – Negotiating Identities women; these writers depicted experiences which were perceived as the norm, describing the condition of ‘all’ women who had impairments, but ignored ethnic minority women’s experiences which are embedded within ethnicity, culture and religion. This absence has meant that little is known of the commonalties and differences between disabled ethnic minority women and disabled White women. Just as the discrimination and disadvantage experienced in the 1970s signalled the emergence of the Black community on the social and political fronts, a Black collective identity also emerged within the field of disability using the collective label ‘Black’. Black women defined a womanhood which is significantly different to the general trends in the women’s movement, by analysing the triple oppression of gender, race and disability, and how these shape the lives of Black women (Lonsdale, 1990). The collectivisation of experiences under the term ‘Black’ has enhanced the chances for the harmonisation of diverse struggles on issues of gender and race, Subsequently writers such as Nasa Begum (1994) and Ayesha Vernon (1998) have encompassed a South Asian female perspective under this blanket term. Amalgamating South Asians within the established category of ‘Black’ in contemporary disability discourse gives the illusion of homogeneity, and fails to analyse the different features of identity. The issues dealt with under the term ‘Black’ are largely around disadvantage and the demand for equality. Differences in lifestyles, for instance in relation to religion, family and marriage give rise to particular issues within these minority communities and are absent from disability discourse. The experiences of South Asian people, in particular women, are intricately connected to their ethnic and cultural background (Hussain et al, 2002). 8 South Asian Women – Negotiating Identities Even the category ‘British South Asian’ has short comings. ‘South Asian’ spans a broad definition which condenses within it specific parameters such as religion. It does however provide theoretical direction, since the term British South Asian focuses on what is culturally and ethnically shared. There are similarities in the position of Muslim, Hindu, Sikh, and Gujrati women that allow a collective reference as South Asian. Ultimately, locating the identity of British South Asian disabled women within established categories inherited from the past proves to be limiting. The implications of this are especially complex when it comes to dealing with disabled people from ethnic minority groups where the idea of hybrid identity emerges (Papastergiadis, 1997). This is part of a more dynamic process, reflecting broader changes in the experience of South Asian young people living in Britain. Young people engage with ethnic, religious and cultural values associated with their parents’ homeland within the context of a Western society. Academic, policy and lay discussion tend to overemphasise ‘cultural conflict’ between young people and their parents, in particular those pertaining to gender (see Brah 1992). Outright rejection of their parents’ ethnic and religious identities is rare among the second generation, although partial and contingent acceptance as well as reinterpretation of some values does occur (AmitTalai and Wulff 1995; Drury, 1991). It is not a question of forsaking one claim for another and choosing between a ‘Western’ or ‘Asian’ way of life (Modood et al, 1994; 1997). Consequently the idea of hybrid identities has emerged to analyse these issues (Papastergiadis, 1997). To what extent do these ethnic, religious and cultural identifications further mediate the experience of disability? Recent research into the lives of young South Asian women growing up with physical impairments shows that issues of difference, gender inequalities and culture 9 South Asian Women – Negotiating Identities are all important (Hussain et al 2002). No young disabled woman is totally detached from their parents’ ethnic, religious and cultural traditions. In fact most young people acquire a good working knowledge of ethnic traditions and religious teachings and identified with them. These young women question their own predicaments, values and responses and recall how they come to terms with their own British South Asian identity and disability. Women in South Asian communities are also the guardians and representatives of family honour, where their role within the family becomes intertwined with notion of izzat, meaning family honour and self-respect. Izzat in Britain faces a new range of threats; for example, should women be allowed to go onto further education, enter employment or choose their own marriage partner? Whilst their British upbringing encourages notions of individuality and independence and also convinces them that they have the ability to earn a living, the notion of filial duty is difficult to shed without incurring feelings of vulnerability and guilt (Afsar, 1989, Wilson 1978). For disabled South Asian women their communities’ views about disability add a further layer of complexity around izzat. Finally, for these women, their body is included in and often compromised by broader social and structural relations (Edwards and Imries, 2003). Disabled women also seek sexual and reproductive rights that are specific to them as disabled people (Lloyd, 2001). These issues remain underdeveloped in disability studies, especially the absence of ethnicity in such considerations. Whilst the literature on gender has engaged with ideas about the body and its social construction, disability discourse continues to marginalise ethnicity and gender. The South Asian female body becomes a site of resistance to the influences of social and ethnic relations. The South Asian community still deploys a medical model of disability that is primarily 10 South Asian Women – Negotiating Identities concerned with the physical body. Consequently for the women their body becomes intricately bound up within a social construction of femininity where their body ultimately becomes ‘text’ (Hughes 1999; Shilling, 1993). For the South Asian women interviewed for this study, the body becomes the site where the power of others is realised, and izzat is one form of this, and wider racism another. They become disabled through the attitudes and norms by which society defines them (Edwards & Imrie, 2003). Thus they battle against ethnically specific expectations with regard to sexuality, reproduction and ideal body images. SOUTH ASIAN FAMILIES AND DISABILITY Literature about South Asian disabled people in the past has largely focused upon the medical model with its emphasis on personal tragedy. Rohina Shah (1986) cites examples of parents who reject their disabled child. They encountered feelings of resentment by other members of their family and felt stigmatised by them. The parents interviewed for this study also saw the birth of a disabled child as a punishment for sins or a test from God (Hussain et. al. 2002). This promoted feelings of inadequacy especially for the mother, and consequently parents failed to prepare for the welfare of their child, assuming that God would protect him/her (Shah, 1986 quoted in Begum, 1992). Because having a disabled child has social and psychological consequences for parents; this became bound up in their relationship with the young person as it affected how the young person made sense of their disability (Hussain et al, 2002; Beresford, 1996; Chamba et al., 1999). Parents became ‘over-protective’, often underestimating the abilities of the young person and thus undermining their ability to exercise control over their lives (Atkin and Ahmad, 2000). Parental concerns specifically focused on issues such as 11 South Asian Women – Negotiating Identities the ability to successfully negotiate transitions that they deemed ‘normal’ for nondisabled children: a good education; social skills; knowledge of parental religions and cultures; and assuming adult roles such as having a job and being married. Parents felt their child’s impairment presented additional and substantial barriers (Hussain et al, 2002). To a large extent, parents saw caring for a disabled child as an extension of their parenting role and one that would continue into adulthood. They felt responsible for all aspects of the child’s life and worried about how their disabled child would cope with adulthood. Parents also expected to be involved in the child’s life far longer than they would for their other children. Such assumptions, however, can create possible tensions between themselves and the young person. Despite having some sense of a social model of disability, families did not entirely transcend their sense of personal tragedy and more general negative views of disability (Hussain et al 2002). Several parents encouraged the young women towards greater independence. This introduced an ongoing tension in the parents’ views of disability. Whilst they regarded their child as vulnerable and unable to have the opportunities available to their other siblings, parents wanted to maximise the opportunities available to their child and encourage independence. Some parents felt the extended family created additional barriers for the family. To this extent, South Asian communities’ disablist attitudes are perhaps no different from the general population (Ahmad, 2000). This also reminds us that that the extended family is often a mixed blessing (Chamba et al. 1998) and sometimes oppressive, providing moral policing but little practical support (Katbamna et al. 2000). Women’s moral identities were perceived within South Asian communities to be more ‘at risk’ than men’s, having consequences for the individual and the family and affecting marriage prospects (Katbamna et al. 2000). Men are agents of the 12 South Asian Women – Negotiating Identities culture yet women are its symbols; the protection of moral identities is fundamental to this, and this shapes gendered responses to disability in ethnically specific ways (Anwar, 1979; Ballard, 1994). All the parents, without a shadow of doubt, wanted the best for their daughters, yet they were clearly more distressed at having a daughter with a physical impairment, and their daughter’s recognised this. According to Saira Iqbal a twenty two year old single Muslim woman who experienced problems with her joints: “If I was a boy, I think it would have been easier ’cos… our Asian people, all they want are sons, they don’t want daughters, they think daughters are useless”. This applied equally to Muslim and Sikh families. The mother of Rupal Bains, a young single Sikh woman who had mobility problems and used a wheelchair, summed up the concerns of many parents: “Sons are sons, they’re boys. You don’t worry about boys, do you, the same way.” Perceived threats to young disabled women’s moral identities were countered by resisting their incursions into the wider social world. The father of Rukhsana Javed (Muslim, Single,19) did not like his daughter, who experienced mobility problems arising from complications associated with kidney failure, attending social clubs for other disabled people, explaining that: “I don’t want her to go along with [the idea] that girls should have male friends.” The young women, themselves, recognised these differences. Jameela Yusaf, a twenty eight year old Muslim woman whose mobility problems arose from a spinal condition, remarked: “Like my brothers, they don’t get stopped, they can go out with friends but it wouldn’t be the done thing for girls within the family. I think they have slightly more freedom than us.” Young women with impairments thus tended to experience greater isolation than young men. Nevertheless, both the young disabled persons and their non-disabled female siblings had to negotiate such issues in similar 13 South Asian Women – Negotiating Identities ways; consequently, disabled young women were not particularly disadvantaged in this respect compared to their able-bodied sisters. These South Asian women tried to exercise some control over their lives with a sense of mutuality, interdependence and ability to reciprocate. They negotiated the meaning of disability as they celebrated their ethnic, cultural and religious differences. Such identifications become especially salient in terms of the ‘second generation’, irrespective of whether they have an impairment. Establishing autonomy and independence is as important to South Asian young women living in Britain as their ‘White’ counterparts, yet assumes different connotations (Atkin and Ahmad, 2000). For disabled women, developing and sustaining an identity separate from their parents and exercising some control over their own lives, however, is not always equated with leaving home and establishing an independent existence (also see Ahmad et al, 2000). The narratives of the young women with physical impairments reflect this. According to Jameela Yusaf, a twenty eight year old Muslim woman with mobility problems: “Within our culture, it’s difficult... I couldn’t say to my parents like I’m going to live independently, like an English person could do that, there would be difficulties”. It is not the norm for young unmarried women to leave the parental home; traditionally, they leave when married. These Asian women have a need to exercise control over their lives with a sense of mutuality, interdependence and ability to reciprocate. They negotiate the meaning of disability as they celebrate their ethnic, cultural and religious differences (Hussain et al, 2002). Such identifications become especially salient in terms of the ‘second generation’, irrespective of whether they have an impairment. 14 South Asian Women – Negotiating Identities RELIGIOUS PRACTICES The primacy of religion in South Asian identities owes at least as much to community relations as to personal faiths, and it marks a significant dimension of cultural difference between the communities and British society. There is very little if any movement between generations from a religious identification to ‘none’ among the younger members of these groups (Modood et al, 1997). For the young women interviewed conforming to the religious practices of their parents was a further expression of their ethnic identity. However, there were different experiences of religious practices between ethnic groups. Most of the Muslim participants practised their faith more readily than their Sikh counterparts. Within the Muslim population there were gender differences, women emphasised the role religion had in their lives more than their male counterparts; for these women it was an integral part of their lives. Young disabled people, irrespective of gender, did not have the same access to religious and cultural socialisation as their non-disabled siblings (see also Ahmad et al, 1998; Hussain et al 2002). A particular problem was religious education and the role of mosques and temples. Attending places of worship was problematic: according to Rajwinder Kaur, a twenty eight year old Sikh woman whose burns have caused her severe mobility problems, “I do feel bad because I wish that I could go, [but] you have to sit on the floor, you see, and it’s hard getting back up”. Religious teachers sometimes failed to accommodate the young person’s impairment or did little to support or encourage them. Fatima, a single Muslim woman aged twenty six with achondroplasia, was made to feel different when she attended the Mosque and was taught in a separate room, away from the other children; she added, “the Imam did not seem that interested in teaching me”. 15 South Asian Women – Negotiating Identities Impairment continued to affect their lives into early adulthood to the point that almost all the young women avoided attending either mosque or temple and religious gatherings in people’s houses on account of the problems they expected to face. For many of the young people interviewed estrangement from such religious occasions seemed to be largely confined to the more formal rituals associated with their religion, in the case of Muslims such as reading the Quran and praying. Humaira Saleem, a single woman aged twenty nine who lost the use of her legs as a child, like other young people, described how her impairment interfered with her observance of religious practices: “Well, I can’t read namaaz properly because I can’t sit down on the floor; I find it difficult”. But for the Muslim interviewees religion was a sufficiently important part of their lives for them to accommodate the difficulties of practice as Mehmoona Akhtar a married Muslim woman aged twenty who had experienced severe hip problems since she was a child says “I can’t sit on the floor but I sit on a chair and read it.” This gendered practising of the Islamic faith, was not accidental. Parents encouraged their daughters more than sons to learn about the religion (Hussain et. al. 2002). This process is not specific to impairment but part of a wider process, reflecting broader changes in the experiences of South Asian young people living in Britain. Young women engaged with the religious values associated with their parents’ homeland, more so than their male counterparts (Modood et al, 1997). The father of Rukhsana Javed, a Muslim single woman aged nineteen who experienced mobility problems arising from complications associated with kidney failure, wanted all his children to learn about religion and go to Mosque: “It gives you peace of mind, a sense of self-worth and it tells you who you are.” 16 South Asian Women – Negotiating Identities Muslims also took a more positive view of disability. The impairment was seen to be given by Allah, who would also provide the family with the resources to cope with the child’s disability (Atkin and Ahmad, 2000). Parents saw this as their responsibility; the mother of Kausar Khalid, a single Muslim girl aged eighteen with mobility problems, said “If God has given me this one, I’ll help her to do everything.” Such sentiments were echoed by the parents of Naseem Javed a single seventeen year old quadraplegic: “God has given us a child like this, so we have got to prove to Him that we will look after her, because she is a Muslim and our daughter.” Whilst the women did not go to places of worship, their religious identity was important. These women were able to learn about Islam by reading at home and talking with other family members. Moreover, most young people knew enough about their religious and cultural values to feel they belonged to their religious community and to behave ‘appropriately’. In many ways, the young women had as much of an awareness of religious and cultural values as their female siblings. The young women found identification with their religious affiliation particularly meaningful. These women turned to Islam for help and guidance during difficult times. Religion emerged as important in all of the girls’ lives. Two of the Muslim women wore the hijab and had done so for quite some time. These women used Islam as a source of strength: according to Miriam, a twenty seven year old with arthritis, talking about her impairment, “The only way you can sort of gain strength and carry on is by just through faith.” She admits: “It helps you lighten the load.” There was a growing awareness of Islam among the girls as a form of empowerment. They talked about the injustices women faced as bearers of their culture and their Islamic faith, and were able to define a concept of Islam which was not a culturally determined set of practices inherited from their parents, but one which 17 South Asian Women – Negotiating Identities was firmly based on the Islamic scriptures. The young disabled women used Islamic principles to argue and convince their parents on several issues. Miriam Hussain, a twenty seven year old with arthritis attributes to this her awareness of women’s rights: “That’s why I've got a translated Quran in English, ’cos they say that man can treat us like this, it’s not true”. The women’s knowledge of Islam framed their perspectives of life and the discrepancies they experienced in everyday life. Therefore religion became a resource that they used to resist parental control. Some of the Sikh families, however, came across more theological barriers to religious practice. For some of these families, their child’s impairment was associated with the sins of a previous life. Such a response could also inform the response of the wider community, even if the parent did not specifically agree with such a view. The mother of Rupal Bains, a twenty year old single woman who used a wheelchair, explained that other people in the Sikh community believe she is being punished for past-life sins: “It’s like the elders, you know, they assume that I’ve been punished for something that I must have done, something wrong in my past life”. It is perhaps not surprising that most of the Sikh young people did not usually subscribe to such beliefs. To do so could be damaging to their sense of self. What was significant about the Sikhs was that although they identified themselves as Sikhs, they had a more negative view of religion. According to Rajwinder Kaur (married, aged 26), who has mobility problems, “I don’t practise it. I don’t like going to temple or anything, I just accept it basically. I don’t follow it.” This opinion of religion was not specific to gender; the Sikh men also had similar opinions, as did both sets of siblings. The parents talked abut religion as being of some importance, yet for their daughters, with impairment or not, it did not have the same significance. The daughters talked about being excluded from the religion due to 18 South Asian Women – Negotiating Identities their inability to access places of worship and the reactions they experienced from others. Rajwinder Kaur added: “I go after a year or something, they’re thinking who’s she? Where’s she come out of?” She feels very bitter at this: “I don’t think religion to many young children is important any more, actually. They’ve got better things in life to do than go to temple or whatever it is.” MARRIAGE Disability had an impact on traditional marriage patterns with the South Asian communities. Traditionally, South Asian daughters are perceived as visitors within parental homes who await the transition to their ‘real’ home with the husband’s family. Marriage also brought about a shift in authority from the father to the husband, consequently women became the izzat of their husbands (Modood et al, 1994). The female non-disabled siblings talked about marriage which involved negotiation with their parents. This is part of a dynamic process reflecting broader changes in the experience of Asian young people living in Britain (Afsar, 1989). But for her disabled sister, impairment added another dimension, differences emerged between the expectations of the disabled young person and their siblings. Young disabled women had less chance of being married than their male counterparts who were more likely to be engaged or involved in negotiations about marriage. The prospect of marriage for a young woman with an impairment was virtually nonexistent; her physical impairment thus prevented her from fulfilling her traditional and conservative role as a homemaker. Parents with a disabled daughter talked about the devastating effect on her marriage prospects, but with sons, it was a different case: there was more hope. The mother of Naseem Javed, a seventeen year old Muslim who had been a quadriplegic since the age of twelve, explains why “Within our culture, girls do not belong to the 19 South Asian Women – Negotiating Identities parents, they belong to the families of the husband she marries… although all parents worry about their daughters, it’s even worse having a daughter like this.” The father of Rukhsana Javed (Muslim, Single; 19) talked about the devastating effect having a disabled daughter who experienced mobility problems has had. Talking about marriage, he says: “Who is going to marry someone like our daughter? If she was normal, we would have got her married by now.” The discussions with the female siblings about their disabled sister evoked similar sentiments. They talked negatively about the marriage prospects for the disabled sister and mirrored the viewpoint of their parents. For instance Rehana, the sister of Humaira Saleem, a single Muslim woman aged twenty nine who lost the use of her legs as a child, reveals the difficulty her sister will face in finding a partner: “You wouldn’t get a husband to actually care for her, would you… she needs 24-hour care… you wouldn’t find a man committed enough to actually look after her all the time, take her to bathroom, give her a shower.” What was interesting was the perception parents and siblings had of the partner as not merely husband or wife but as carer. Parents and siblings continually referred to the partner in the role of the carer, they wanted their sons to get married so that their wives could take over the role of the carer which they had been filling. However, this was different for the women, given the domestic expectations of married woman. Family members defined the disability as a burden and undesirable and unfair for a man. Being unmarried was therefore an accepted fact within the family and seemed to be an inevitable consequence of having a disability. From the perspective of the young women, they all saw marriage as a desirable part of life, but none of them envisaged this as a real possibility. None of the women had been asked if they would like to marry, nor had they even assumed 20 South Asian Women – Negotiating Identities they would find a marriage partner. Yet in reality finding a partner independent from family intervention was difficult (Hussain et al, 2002). The girls realised this and began to assimilate the negative views perpetuated through their family, expressing guilt at having a disability and the suffering they were causing their parents. One respondent, Miriam Hussain, a twenty seven year old Muslim with arthritis, talked about her mother’s disappointment in her: “Sometimes she gets upset, saying I wish you were okay, you’re so pretty and this and that and the other, you need a husband to take care of you.” This negative view from the family filtered down to the women themselves. For instance, Jameela Yusaf, a twenty eight year old Muslim woman whose mobility problems arose from a spinal condition, said: “I wouldn’t be able to cope, I don’t think anyway… I don’t think it’s fair on the other person who you are getting married to. I couldn’t see myself coping and bringing up a family and things like a normal lady would be expected to do. I couldn’t do that, there’s no way.” This was a view shared by many others, including Saira Iqbal (Muslim; Single; 22) who had problems with her joints: “I don’t wanna get married, ’cos I don’t think I could ever cope with, you know, married life… it’s hard work.” Five women in total were married, and all but one of the partners came from India or Pakistan (the one remaining migrated to Britain from Barbados). Two of the five had married during their impairment, Rajwinder Kaur, a Sihk woman aged twenty six who experienced mobility problems aged 28. Both had been married with their physical impairment restricting their mobility, but had very different experiences. Nazia felt lucky to be married. “people wouldn’t have given me a marriage partner but because it was my dad’s brother’s son, he therefore agreed to marry me”. Rajwinder Kaur experienced problems with her marriage and felt she had to accept second best because of their impairment and believe their siblings were 21 South Asian Women – Negotiating Identities likely to find more suitable partners. Rajwinder said that her sister got the better husband: “Compared to my husband he’s much cleverer, he speaks English and everything, he’s more westernised. Yes, I think I could have done better. I think the only reason I ended up with my husband is because of my disability. I ended up with him because of my leg. I know I could’ve done better.” She was on the verge of leaving her husband and had informed her family of her intentions. Rajwinder Kaur’s experiences were echoed by the other women who were married. All the other women were all experiencing problems with their marriage and believed themselves to be a burden to their partner. These women were married before their disability was diagnosed or before they had limited mobility, yet they talked about the effect of the impairment on their relationship. Sukwinder Kaur (Sikh, married, 30), an MS patient, spoke of husband’s refusal to acknowledge her disability because she appears ‘alright’ physically. He refuses to do any domestic chores in the home, so she has to rely on her daughter or home help to clean her home: “I have asked him to do it, but he goes why are you here? You are here to clean up. I’ve been to work, I can’t be cleaning up.” He accuses her of being lazy: “he thinks most of the things that I can’t do, I should be able to do, like looking after the house and cleaning”. Her husband has filed for divorce without informing her: “He wants a divorce and still to live with me and get married and bring another woman in the house.” Parents felt it was easier to bring marriage partners from overseas rather than try to secure partners in Britain. By comparison, able-bodied siblings seem more likely to marry someone from Britain, although several were considering marriage partners from overseas. There were various reasons for seeking overseas marriage partners and most seem to have been informed by the young person’s disability. First, 22 South Asian Women – Negotiating Identities partners from overseas were seen as not having high expectations and therefore more willing to enter Britain and look after a disabled person. This is perhaps ironic, given that young people feel South Asian cultures are too traditional (Hussain et. al. 2002). Second, young people and their parents remarked that by considering marriage partners from South Asia they were offering entry in to Britain: a much sought-after option among those living in India and Pakistan. This, however, could have its disadvantages. Several young people and their parents were concerned that some prospective partners were using marriage as an excuse to enter Britain and had no intention of trying to make the marriage work. Entry to Britain was felt to be a particular issue for prospective husbands. This is a particular worry for Miriam Hussain, a twenty seven year old Muslim with arthritis. She has been engaged twice but was worried that her prospective husband is using it as an excuse to settle in Britain. She does not understand why anyone would want to take on a wife with an impairment “I would never be sure that, if they just did it just to get a ticket over here, so I wasn’t too keen”. Although the bulk of the women were reconciled to the idea of not marrying, there were others who were adamant about finding a partner. These women talked about their desire to marry even if it meant having a partner from outside their culture. Several had concealed relationships with non-Asians from their families, to avoid offending traditional sensitivities. Humaira Saleem, a single Muslim woman aged twenty nine who lost the use of her legs as a child, talked about her three-year relationship with her White boyfriend, whom she met at the local community centre. Her reluctance to enter into a relationship with a South Asian man is clearly evident and has to do with the control she anticipates: “The way they treat their wives, tell them what to do and what not to do”. Her relationship was conducted clandestinely at 23 South Asian Women – Negotiating Identities the centre. She also visited his home and met his parents, but the relationship ended when she asked him to change his religion: “I wanted him to change his religion and to become a Muslim, so I could teach him the Quran… and he comes out with it, he doesn’t want to do that and then he told me to change my religion… I couldn’t.” Her parents knew nothing of the relationship, but she knows their likely response: “If my family had known they’d have probably killed me!” Marriages within these families were being handled in a traditional way. Negotiated and arranged marriages took place. Few parents or young people suggested that their impairment would fundamentally alter traditional marriage patterns. The mother of Rupal Bains, a young single Sikh woman who had mobility problems, was one of the few parents who did. Her primary concern was to ensure her daughter married a husband who would look after her: “I would never arrange for her, because then that would be unfair… we could find her somebody but we do not know if he will care for her. So it’s best she found somebody herself” This was an exception, a mother encouraging her daughter to pursue a love marriage and leaving selection entirely in the hands of her daughter. In other cases there was scepticism about romantic love and western-style marriage, with some citing religious reservations. Miriam Hussain, a twenty seven year old with arthritis said: “I wouldn’t go out with anybody. I always have male friends, but I won’t let them pass that limit.” Her reasons are embedded in religion: “I don’t wanna, ’cos it tells me not to in the Muslim religion.” But those who were on the lookout anticipated problems. On the other hand, a few of the women who had displayed a desire for marriage anticipated problems. Many who would like to get married envisaged problems not from the family but from prospective partners. Rakinder Sohota, another Sikh interviewee with MS admits finding a partner would 24 South Asian Women – Negotiating Identities be problematic due to her disability: “I don’t want a situation where I do meet someone and I’m having to tell them about my disability… I’ve found with people…they had partners who’ve left them because of their disabilities.” Because of this, “I think I’ll just be on my own, I mean I’d like to sort of have a partner or get married, but I can’t see myself doing it”. CONCLUSION The meaning of disability in British South Asian communities is neglected and remains poorly understood in current debates in disability studies. These debates tend to assume a universal social model of disability that has been criticised by disabled women from a feminist perspective. However, such criticisms created their own new universal White subject often neglecting the specific circumstances of disabled ethnic minority women especially in relation to the regulation of sexual behaviour, marriage and religious practices. This paper has attempted to redress these imbalances through the analysis of empirical data on these issues. All the young women interviewed were capable and efficient, active, vigorous and energetic, but at the same time appeared submissive and compliant as each limited their behaviour to some degree in order to meet cultural expectations and avoid conflict with their parents. All are aware of their parent’s expectations for them but also consciously motivated by their own interests and desires. From the disabled young person’s point of view her experience was different to that of her able-bodied siblings. For both Muslim and Sikh women marriages were difficult to arrange or negotiate and the minority who had husbands sometimes felt that they had married ‘less well’ than their sisters, often marrying new migrants rather than British born husbands. However, despite cultural expectations that all South Asian women would 25 South Asian Women – Negotiating Identities get married, the likelihood for many young women in this study was that they would not get married. All the young women interviewed had internalised the appropriate attitudes, values and forms of social behaviour as dictated by their ethnic, cultural and religious values. These values became an integral to the identity of these women, more so than their male counterparts (Hussain et al, 2002). Social control therefore was not exercised through punishment for transgressing against society, but through internalised norms often associated with izzat. To a large extent, their narratives are similar to their able-bodied siblings in this respect. The family ultimately had a major role to play in these young women’ lives. The parents often had their daughters’ best interests in mind and these forms of control ensured the young women stayed within the ethnic and cultural framework; it became a means of social and family control. Religious affiliations are of increasing significance among British South Asians now challenging the notion of a ‘South Asian’ identity. Religion was especially important for the Muslim women in this study. However, despite positive views amongst Muslims towards disabled people organised religion in Mosques and at Sikh temples failed to cater adequately for the needs of the young disabled women. Overall the empirical findings suggest that there is range of issues that are specific to the positioning of young South Asian disabled women: around sexuality and control of the body, real marriage prospects as opposed to expectations and access to collective religious practices. Exploring identities is a complex undertaking, especially when the potential axis of identity claims are so numerous and contested as in this study. The young women’s opinions and views presented here offers no support to notions of singular identities or of a hierarchies of identifications, it shows that identity claims of disabled 26 South Asian Women – Negotiating Identities young people were negotiated and contingent, allowing some freedoms within contexts in which ethnicity, religion, gender, social status, racism, generational relations and the meaning of being disabled were important considerations. It also suggests that the findings may apply to South Asian groups more generally. 27 South Asian Women – Negotiating Identities Acknowledgments The support of the Joseph Rowntree Foundation which funded the research upon which the paper is based upon is gratefully acknowledged, in particular Dr Emma Stone. Thanks also goes to Dr Karl Atkin, Professor Waqar Ahmad and Dr Paul Bagguley. REFERENCES Afsar, H., (1989) 'Gender Roles and The Moral Economy of Kin Among Pakistani Women in West Yorkshire', New Community, 15: 211-25. Ahmad, W.I.U., (2000) Ethnicity, Disability and Chronic Illness, Buckingham: Open University Press. Amit-Talai, V. and Wulff, H., (1995), Youth Cultures: a Cross-Cultural Perspective, London: Routledge. Anwar, M., (1979), Myth of Return: Pakistanis in Britain, London: Heinemann Educational. Atkin, K. and Ahmad, W.I.U., (2000) 'Living with a Sickle Cell Disorder: How Young People Negotiate their Care and Treatment', in Ahmad, W.I.U. (ed) Ethnicity, Disability and Chronic Illness, Buckingham: Open University Press. Ballard, R., (ed.), (1994), Desh Pardesh, The South Asian Presence in Britain, London: Hurst. Basit, T. N., (1997) Eastern Values, Western Milieu: Identities and Aspirations of Adolescent British Muslim Girls, London: Aldershot: Ashgate. Begum, N. (1992) Something to be Proud of, (London, London Borough Of Waltham Forest). Begum, N. (1994) Reflections: The Views of Black Disabled People on their Lives and Community (London, Central Council for Education and Training in Social Work). Boylan, E. (ed) (1991) Women and Disability, London: Zed Books. Brah, A. (1992) 'Women of South Asian origin in Britain', in P. Braham, A. Rattansi and R. Skelllington (eds.) Racism and Anti-Racism: Inequalities, Opportunities and Policies, London: Sage. Bulmer, M. and Solomos, J., (1999), Ethnic and Racial Studies Today, London: Routledge. 28 South Asian Women – Negotiating Identities Chamba, R. Hirst, M. Lawton, D. Ahmad, W. and Beresford, B. (1999) Expert Voices: A National Survey of Minority Ethnic Parents Caring for a Severely Disabled Child, Bristol: Policy Press. Corker, M. and French, S. (eds) (1999) Disability Discourse, Buckingham: Open University Press. Drury, B. (1991) Sikh Girls and the Maintenance of Ethnic Culture, New Community, 17(3): 387-99. Edwards, C. Imrie, R, (2003), ‘Disability and Bodies are Bearers of Value’, Sociology, 37 (2): 239-56. Hughes, B. (1999), ‘The Construction of Impairment: Modernity and the Aesthetic of Oppression’, Disability and Society, 13(2): 155-72. Hussain, Y. (2005 forthcoming), Writing Diaspora: South Asian Women, Culture and Ethnicity, Ashgate Aldershot, London. Hussain, Y., Atkin, K., Ahmad, W.I.U., (2002), South Asian Disabled Young People and their Families, Bristol: Policy Press. Lonsdale, S. (1990) Women and Disability, London: Macmillan. Katbamna, S., Bhakta, P. And Parker, G. (2000) Perceptions of disability and care giving relationships among South Asian Communities in Ahmad, W.I.U. (ed) Ethnicity, Disability and Chronic Illness, Buckingham: Open University Press. Modood, T, Beishon, S and Virdee, S (1994) Changing Ethnic Identities, London: Policy Studies Institute. Modood, T, Berthoud, R, Lakey, J, Nazroo, J, Smith, P, Virdee, S, Beishon, S (1997) Ethnic Minorities in Britain: Diversity and Disadvantage (Fourth PSI Survey), London: Policy Studies Institute. Oliver, M. (1996) Understanding Disability: From Theory to Practice, Basingstoke: Macmillan. Papastergiadis, N., (1997), 'Tracing Hybridity in Theory' in Werbner, P; Madood, T, Debating Cultural Hybridity; Multi-Cultural Identities and the Politics of AntiRacism, London: Zed Books. Parmar, P., (1982), 'Gender, Race and Class: Asian Women in Resistance'; in Centre for Contemporary Cultural Studies, The Empire Strikes Back: Race and Racism in 70’s Britain, London: Routledge. Rex, J., (1997), The Ethnicity Reader: Nationalism, Multiculturalism, and Migration, Cambridge: Polity Press. Shilling, C. (1993), The Body and Social Theory, London: Sage. 29 South Asian Women – Negotiating Identities Vernon, A. (1998) Understanding simultaneous oppression : the experience of disabled black and minority ethnic women, PhD thesis, University of Leeds. Werbner, P., (1997) The Migration Process: Capital, Gifts and Offerings among British Pakistanis, London: Berg. Wilson, A. (1978) Finding a Voice: South Asian Women in Britain. London: Virago. 30