Bad stuff, that DNA

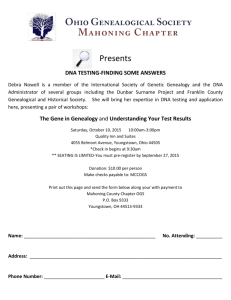

advertisement