Paradigm Shifts in Quality Improvement in Education

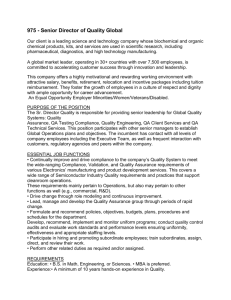

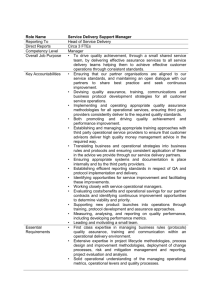

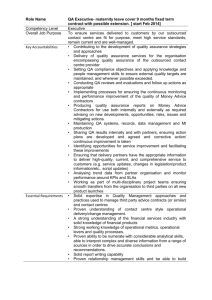

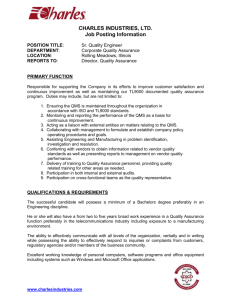

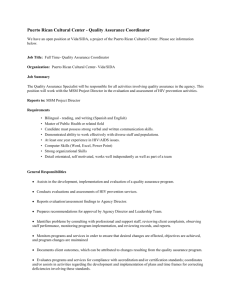

advertisement