here - Derwent Estuary

advertisement

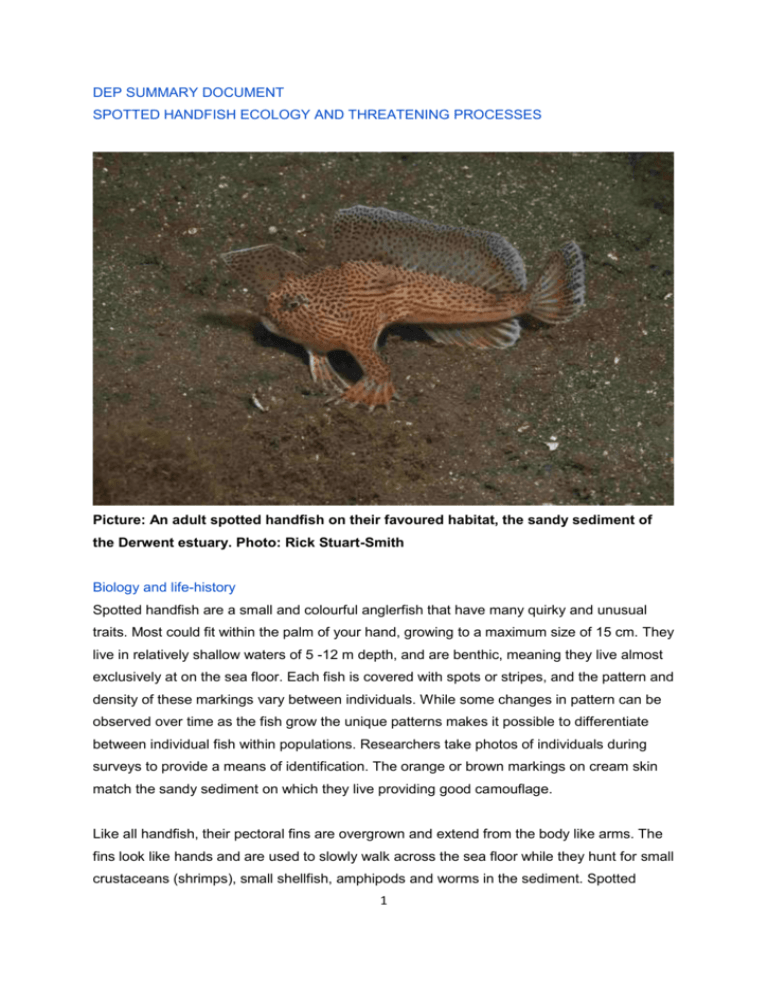

DEP SUMMARY DOCUMENT SPOTTED HANDFISH ECOLOGY AND THREATENING PROCESSES Picture: An adult spotted handfish on their favoured habitat, the sandy sediment of the Derwent estuary. Photo: Rick Stuart-Smith Biology and life-history Spotted handfish are a small and colourful anglerfish that have many quirky and unusual traits. Most could fit within the palm of your hand, growing to a maximum size of 15 cm. They live in relatively shallow waters of 5 -12 m depth, and are benthic, meaning they live almost exclusively at on the sea floor. Each fish is covered with spots or stripes, and the pattern and density of these markings vary between individuals. While some changes in pattern can be observed over time as the fish grow the unique patterns makes it possible to differentiate between individual fish within populations. Researchers take photos of individuals during surveys to provide a means of identification. The orange or brown markings on cream skin match the sandy sediment on which they live providing good camouflage. Like all handfish, their pectoral fins are overgrown and extend from the body like arms. The fins look like hands and are used to slowly walk across the sea floor while they hunt for small crustaceans (shrimps), small shellfish, amphipods and worms in the sediment. Spotted 1 handfish are fairly sedentary and live in loose groups or colonies of tens to hundreds of individuals. Fewer than 10 colonies are known to exist with the Derwent estuary. As each colony is separated by considerable distance, dispersal between colonies is likely to be low. Spotted handfish have interesting breeding habits. Colonies come together during September and October for spawning. This involves laying an interconnected mass of 80– 250 eggs on semi-rigid vertical objects attached to the sea floor. The most commonly used spawning substrate are stalked ascidians (Sycozoa sp.), sponges, seagrasses or seaweeds. The female stands guard over the eggs for the 6 - 8 weeks until hatching, to protect them from predation. Fully-formed juveniles (6 mm to 7 mm long) hatch from each egg and drop to the substrate below. Juveniles are thought to remain in the general vicinity of spawning. Low dispersal of juveniles has major implications on their conservation. Firstly, low mixing between colonies means that any reductions in the spawning success may seriously impact a colony. Second, the ability for spotted handfish to recolonise areas from which they have been displaced is likely to be low. They are highly vulnerable to changes in their environment due to their scarcity, patchy distribution, life history strategy, low breeding rate and poor dispersal ability. Picture: A female spotted handfish guarding her egg mass attached to a sea tulip (stalked ascidian). Photo: Mark Green, CSIRO 2 Species in decline The spotted handfish was first collected by the French explorer Francois Peron in the 1790s, and was one of the earliest named fish from Australian waters. The species was once common throughout the lower Derwent estuary, Frederick Henry Bay, D'Entrecasteaux Channel and the northern regions of Storm Bay. Prior to the mid-1980s it was frequently sighted by divers along the eastern and western shores of the Derwent estuary. By the late 1990 spotted handfish had suffered a serious decline in distribution and abundance. It now appears that they are largely confined to isolated areas within the lower Derwent estuary. Due to the speed of their decline in range and abundance the spotted handfish became the first marine fish to be listed as ‘endangered’ under the Federal Environment Protection and Biodiversity Protection Act 1999, and was followed by a similar listing by the Australian Society for Fish Biology in 1994, as well as state protection in 1995 under Tasmania's Threatened Species Protection Act 1995. In 1996 it was subsequently listed by the IUCN as ‘critically endangered’. The ‘Spotted handfish Recovery Plan 1999-2001’ [LINK], released by the Tasmanian Government, and the ‘Recovery Plan for four species of handfish’ [LINK] released by the Commonwealth’s Department of Environment outline priority actions for key threatening processes. Key threats to spotted handfish are changes in the benthic community which may result in direct or indirect impacts, and include: -depletion of spawning substrate by introduced Northern Pacific seastars (Asterias amurensis); -depletion of spawning substrate due to pollution from industrial storm water and sewage; -loss of critical habitat due to increasingly silty sediments caused by land clearing; and -coastal developments, particularly those that involving dredging Because handfish live in shallow coastal environments in close proximity to major urban and industrial areas they are exposed to man-made impacts. Changed land practices over the long term have increased soil runoff resulting in siltier sediments within the Derwent estuary. Dredging or damage to the sea floor also occurs from coastal development and fishing practices. These combined processes have reduced the amount of natural sandy habitat and changed the benthic community. Pollution also impacts the benthic habitat where handfish feed and breed. Warming waters due to climate change are also considered to affect these rare fish. 3 The introduced northern Pacific seastar is now abundant in many areas where spotted handfish used to occur. These seastars have not yet been observed directly feeding on spotted handfish egg masses, but they do prey on the stalked ascidian and other benthic substrates commonly used for spawning. The disappearance of ascidians, sponges and sea weeds from the sea floor due to sea stars, siltation and other impacts, is a major problem for handfish. These fixed structures protruding from the flat sandy sea floor are a key element for breeding as they provide substrate on which handfish can attach their freshly laid eggs. In the absence of any spawning substrate handfish cannot guard their egg masses to ensure that they hatch successfully. Instead, any eggs that are laid will be swept away in the current. In some handfish colonies years of poor breeding are evident as they have an aging population, with few or no juvenile. Low or no recruitment of young fish will lead to the eventual extinction of these colonies. Personal collection and the aquarium trade also threaten handfish populations by removing individuals from the wild. Picture: Spotted handfish with Northern Pacific seastar (Asterias amurensis) and sea tulips (stalked ascidians). Photo: Mark Green-CSIRO 4 Management actions Spotted handfish are protected under State and Federal Government legislation, and a recovery plan has been prepared to guide management actions into the future. The Red handfish (Brachionichthys politus), Ziebell’s handfish (Sympterichthys sp.), Waterfall Bay handfish (Sympterichthys sp.) are also threatened species, and are included in this recovery plan. Since 1996, a number of actions have been carried out in accordance with various earlier recovery plans, with support from the state and federal government, the CSIRO, NRM South, and IMAS. These include the collection of baseline biological data, examination of habitat requirements, development of techniques to assess population size and stability, monitoring of known colonies, surveys of new potential habitat and the establishment of captive husbandry protocols. Between 1996 and 1999 a captive breeding program was trialled by the CSIRO, resulting in 185 juvenile spotted handfish being released into the wild in 1999. After early failures the highest rate of hatchling survival in captivity was recorded in 1998/1999. The young fish were tagged and released, however no sightings of tagged handfish were suggests high mortality post release. CSIRO scientists have also developed methods to improve spawning success in the wild using a combination of artificial spawning substrates (vertical plastic rods embedded in the seafloor) and natural substrates (transplanted algae) to make up for the decline of natural substrate (e.g. sea tulips). In 2002, algae (Caulerpa sp.) was transplanted from Frederick Henry Bay to a site in the lower Derwent estuary at which spawning substrate was depleted. These algae are used as spawning substrate at the Frederick Henry Bay, and initial results at the site in the lower Derwent estuary have also been encouraging. However, Caulerpa sp. can only be transplanted to sites with suitable salinity and light levels within the estuary. A grant awarded to the DEP by the Federal Government’s Caring for Our Country program is supporting additional surveys and improvements to spawning substrate at several sites in the Derwent estuary. This work aims to build on existing knowledge of spotted handfish distribution and abundance within the Derwent estuary. Plant outs of artificial substrate at a range of sites aim to provide enough suitable spawning habitat for existing populations. The provision of additional structures on which breeding fish can attach their eggs will hopefully see an increase in egg survival and recruitment of young fish into the population. Future work to assess whether artificial substrate have resulted in a recruitment of juvenile handfish would be of value to assess the effectiveness of the recovery program. This work 5 is being undertaken by volunteer divers in collaboration with ReefLife Survey, CSIRO, IMAS, TAFI, Veolia Environmental Services and Aquenal Pty Ltd. Numerous participants have made generous in-kind offers of support, all of which are greatly appreciated. DEP led work has already yielded some positive results with indications of population expansion at two spotted handfish local populations identified on the western shore. Current recovery actions include: Spotted handfish population surveys (at 3 sites), with capacity building of a core group of community-based divers to assist in monitoring and undertake surveys; Installation of artificial substrates at two or three colonies with aging fish populations and a lack of suitable spawning habitat; Maintenance of artificial substrates over time; Assessment of artificial substrate use during spawning; and, Resurvey to monitor the effectiveness of project outcomes. Picture: Scuba survey of spotted handfish habitat in the Derwent estuary. Photo: Mark Green-CSIRO Cautious optimism There have been significant improvements in the treatment of sewage, industrial wastes 6 and stormwater discharged to the Derwent estuary as a result of more than $100 million invested by industries and local governments in the last decade. It is hoped that these environmental improvements – combined with targeted recovery actions to improve handfish spawning success – will lead to the recovery of this unique species over time. However, there is currently no active management of the introduced northern Pacific seastar, and no signs of a breakthrough in their bio-control. This means that these pests are constantly removing natural spawning substrate from the sea floor. We must keep up the hard work to provide alternative spawning habitat for spotted handfish, and integrate new and improved management ideas to ensure the survival of this very special inhabitant of the Derwent estuary. Picture: Spotted handfish adult with juvenile. Photo: Mark Green-CSIRO Close relatives: Fifty million years ago handfish were present in many of the world's oceans, but today they are confined to the south-east of Australia. The handfish family Brachionichthyidae are the most species-rich of the few marine fish families endemic to Australia. There are 14 species, nine of which were only described in 2009. Tasmania is a hot spot for handfish with six species endemic to the state. Many of these Tasmanian endemics have a greatly restricted range occurring in one to a couple of estuarine systems and coastal bays. The Ziebell’s handfish (Sympterichthys sp.) and Waterfall Bay handfish (Sympterichthys sp.) (a colour 7 morph of Ziebell's Handfish) are both restricted to the Tasman Peninsula. Both species were listed as Vulnerable under the EPBC Act in 2000. The red handfish (Brachionichths politus, or Thymichthys politus) considered to be restricted to the Tasman Peninsula and Frederick Henry Bay, was listed as a threatened species under the EPBC Act in 2004. The Pink Handfish, is known from only four specimens and was last recorded off the Tasman Peninsula 8