Astr604-Ch4

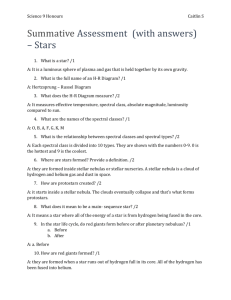

advertisement

1 The basic stellar structure equations require information concerning the physical properties of the matter from which the star is made. The required conditions are the equations of state of the material and are collectively referred to as constitutive relations. Specifically, it is necessary to obtain relationships for the pressure, the opacity, and the energy generation rate, in terms of fundamental characteristics of the material: the density, temperature, and composition. In general, P P ( ,T , composition) ( ,T , composition) ( ,T , composition) (4.1) The pressure equation of state can be quite complex in the deep interiors of certain classes of stars, where the density and temperature can become extremely high. However, in most situations, the ideal gas law, combined with the expression for radiation pressure, is a good first approximation, particularly when the variation in the mean molecular weight with composition and ionization is properly calculated. The opacity of the stellar material can not be expressed exactly by a simple formula. It is actually calculated explicitly for various compositions at specific densities and temperatures and presented in tabular form. Stellar structure codes either interpolate in a densitytemperature grid to obtain the opacity for specified conditions, or alternatively, a “fitting function” can be generated based on the tabulated values. A similar situation also occurs for accurate calculations of the pressure equation of state. 1) Pressure equation of state Interior of a star contains a mixture of ions, electrons, and radiation (photons). For most stars (exception very low mass stars and stellar remnants) the ions and electrons can be treated as an ideal gas. Total pressure: p p i pe p r p gas p r , (4.2) where pi is the pressure of ions, pe is the electron pressure and pr is the radiation pressure. 1.1 Gas Pressure The equation of state for an ideal gas is: PV NkT , (4.3) 2 where V is the volume of the gas, N is the number of particles, T is the temperature, and k is Boltzmann’s constant. The ideal gas equation can be rewritten as Pgas nkT (4.4) where n is the number of particles per unit volume n º N /V (particle number density). In astrophysical applications it is often convenient to express the ideal gas law in an alternative form. Since n is the particle number density, it is clear that it must be related to the mass density of the gas allowing for a variety of particles of different masses, it is then possible to express n as n , m (4.5) where m is the average mass of a gas particles. Then the ideal gas law becomes, Pgas kT m . (4.6) We now define a new quantity, the mean molecular weight, as m mH (4.7) where mH = 1.67x10-24 g is the mass of hydrogen atom. The mean molecular weight is just the average mass of a free particle in the gas, in units of the mass of the hydrogen atom. n (4.8) m H The ideal gas law can now write in terms of the mean molecular weight as: p gas m H kT (4.9) Problem (1): Estimate the central temperature of the Sun using the central pressure value ( Pc 2.7x1015dynes cm -2 , and the molecular weight =0.62 which is appropriate for complete ionization). Neglect the radiation pressure term. 1.2 Determining The mean molecular weight is dependent on the composition of the gas as well as the state of ionization of each species. The determination of m for a completely neutral gas: 3 åN m = åN j mn j j (4.10) j j where mj and Nj are the mass and the total number of atoms of type j that are present in the gas and the sums are assumed to be carries out over all types of atoms. Dividing by the mass of the hydrogen atom, åN A = åN j n j j (4.11) j j where A j º m j / m H . Similarly, for a completely ionized gas i å N jAj j å N j (1 + z j ) (4.12) , j where zj is the number of free electrons that result from completely ionizing an atom of type j. generally it is more useful to express the mean molecular weight in terms of mass ratios, known as mass fractions, rather than numbers of particles. Consequently, we will define the mass fractions of hydrogen (X), helium (Y), and metals (Z) “In some applications, it is necessary to be specify the composition in greater detail. In these cases each species is represented by its own mass fraction” to be X º total mass of hydrogen , total mass of gas Y º total mass of helium , total mass of gas Z º total mass of metals . total mass of gas Clearly, X+Y+Z=1. By inverting the expression for m , it is possible to write alternate equations for in terms of the mass fractions. Recalling that m = m H , Eq. (4.10) for a neutral gas gives åj N j total number of particles 1 = = n m H å N j m j total mass gas j 1 number of particles from j mass of particles from j =å x n m H mass of particles from j total mass of gas j Nj 1 1 =å X j =å X n m H j N j A j mH j A j mH j Where Xj is the mass fraction of atoms of type j. Solving 1/, we have 4 1 n 1 X j, Aj =å j (4.13) Thus, for a neutral gas, 1 1 1 X Y 4 A n Where 1/ A n (4.14) Z. n is a weighted average of all elements in the gas heavier than helium. For the solar abundances, 1/ A 1/15.5 . n The mean molecular weight of a completely ionized gas may be determined in a similar way. It is necessary only to include the total number of particles contained in the sample, both nuclei and electrons. For instance, each hydrogen atom contributes one free electron, together with its nucleus, to the total number of particles. Similarly, one helium atom contributes two free electrons plus its nucleus to the total number of particles. Therefore, for a completely ionized gas, Eq. (4.13) becomes 1 j 1+z j =å Aj j X j. (4.15) Including hydrogen and helium explicitly, we have 1 i 3 1+z 2X Y 4 A (4.16) Z. i For elements much heavier than helium, 1 + z j z j , where z j >> 1 represents the number of protons (or electrons) in an atom of type j. It also holds that A j 2z j , the relation being based on the fact that sufficiently massive atoms have approximately the same number of protons and neutrons in their nuclei, and those protons and neutrons have very similar masses. Thus 1+ z A i 1 . 2 If we assume that X=0.70, Y=0.28, and Z=0.02, a composition typical of younger stars, then with these expressions for the mean molecular weight, n = 1.30 and i = 0.62 . Problem (2): Calculate the mean molecular weight of the Sun, use the values X=0.71, Y=0.27, and Z=0.02. 5 1.3 Radiation pressure At high temperature the radiation pressure has to be added to the gas pressure described by the perfect gas equation. The pressure exerted by radiation is given by the following equation: p rad 1 aT 4 , 3 (4.17) where the radiation constant a 4 / c 7.56591x10-15erg cm-3K-4 . In many astrophysical situations the pressure due to the radiation can actually exceed the gas pressure by significant amount. In fact it is possible that the magnitude of the force due to radiation pressure can become sufficiently great that it surpasses the gravitational force, resulting in an overall expansion of the system. Combining both, the ideal gas and radiation pressure terms, the total pressure becomes p kT 1 aT 4 . m H 3 (4.18) 2) Stellar energy sources The rate of energy output of stars (their luminosity) is very large. What is the source of that energy? One measure the life time of a star must relate how long it can sustain its power output. We have three possibilities can be assumed to be sources of energy production. 2.1 Gravitational potential energy The gravitational potential energy of a system of two particles is given by U = - G M m . As r the distance between M and m diminishes, the gravitational potential energy becomes more negative, implying that energy must have been converted to other forms, such as kinetic energy. If a star can manage to convert its gravitational potential energy into heat, and then radiate that heat into space, the star may be able to shine for a significant period of time. However, we must also remember that by the virial theorem the total energy of a system of particles in equilibrium is one-half of the system’s potential energy. Therefore only one-half of the change in gravitational potential energy of a star is actually available to be radiated away; the remaining potential energy supplies the thermal energy that heats the star. Calculating the gravitational potential energy of a star requires consideration of the interaction between every possible pair of particles. This is not as difficult as might first seem. The gravitational force on a point mass dmi located outside of a spherically symmetric mass Mr is 6 dFg ,i G M r dmi r2 and is directed toward the center of the sphere. This force is one that would exist if all of the mass of the sphere were located at its center, a distance r from the point mass. This implies that the gravitational potential energy of the point mass is dU g ,i = - G M r dm i . r Rather than considering an individual point mass, if we assume that point masses are distributed uniformly within a shell of thickness dr and mass dm (where dm is the sum of all the point masses dmi), then dm 4r 2 dr , where ρ is the mass density of the shell and 4r 2 dr is its volume. Thus dU g = - G M r 4 r 2 dr . r (4.19) Integrating overall mass shells from the center of the star to the surface, its total gravitational potential energy becomes R U g 4G M rrdr , (4.20) 0 where R is the radius of the star. Exact calculation of Ug requires knowledge of how ρ, and consequently Mr depends on r. Nevertheless, an approximate value can be obtained by assuming that ρ is constant and equal to its average value, or ~= M , 4 R3 3 where M is the total mass of the star. Now we may also approximate Mr as Mr 4 3 r . 3 If we substitute into Eq. (4.20), the total gravitational potential energy becomes Ug ~ 2 16 2 3 GM 2 G R5 ~ 15 5 R (4.21) Lastly, applying the virial theorem (total energy =1/2 gravitational energy), the total mechanical energy of the star is E~ 3 GM 2 10 R (4.22) 7 Problem (3): Derive Equation (4.21) in more details, starting from Equation (4.19). Problem (4): (a) If the Sun were originally much larger than that it is today, how much energy would have been liberated in its gravitational collapse? Assuming that its original radius was Ri, where Ri >> 1R๏. (b) Calculate the dynamical timescale of the Sun, assuming that the luminosity is roughly constant. 2.2 Chemical reactions Another possible energy source involves chemical processes. However, since chemical reactions are based on the interactions of orbital electrons in atoms, the amount of energy available to be released per atom is not likely to exceed more than 1 to 10 eV, typical of the atomic energy levels in hydrogen and helium. Given the number of atoms present in a star, the amount of chemical energy available is also far too low to account for the Sun’s luminosity over a reasonable period of time. Problem (5): Assuming that 10 eV could be released by every atom in the Sun through chemical reactions, estimate how long the Sun could shine at its current rate through chemical processes alone. For simplicity, assume that the Sun is composed entirely of hydrogen. Is it possible that the Sun’s energy is entirely chemical? Why or why not. 2.3 Nuclear reactions Already in the 1930’s it was generally accepted that stellar energy had to be produced by nuclear fusion. In 1938 Hans Bethe and independently Carl Friedrich Von Weizsäcker put forward the first detailed mechanism for energy production in the stars, the carbon-nitrogen-oxygen (CNO) cycle. The other important energy generation process (the proton-proton chain and the triple-alpha reaction) were not proposed until 1950’s. The nuclei of atoms may be considered as sources of energy. Whereas electron orbits involve energies in the eV range, nuclear processes generally involve energies millions of time larger (MeV). Just like chemical reactions can result in the transformation of atoms into molecules or one kind of molecule into another, nuclear reactions change one type of nucleus into another. The nucleus of a particular element is specified by the number of protons, Z, it contains with each proton carrying a charge of +e. We often refer to Z as the atomic number [e.g. H (Z=1), He (Z=2), C (Z=6), N (Z=7), O (Z=8), Ne (Z=10), and Fe (Z=26)]. In neutral atom the number of 8 protons must exactly equal the number of orbital electrons. An isotope of a given element is identified by the number of neutrons, N, in the nucleus, with neutrons being electrically neutral [Isotopes of an element have the same atomic number but different number of neutrons N, e.g. 1H (ordinary hydrogen), 2H (deuterium), 3H (tritium)] . All isotopes of a given element have the same number of protons. Collectively, protons and neutrons are referred to as nucleons, the number of nucleons in a particular isotope being A=Z+N. Since protons and neutrons have very similar masses and greatly exceed the mass of electrons. A is a good indication of the mass of the isotope and is often referred to as the mass number (The quantity Aj defined in Eq. (4.11) is roughly equal to the mass number). The masses of the proton, neutron and electron are respectively, m p = 1.672623x10-24g , m n = 1.674929x10-24 g and me = 9.109390x10-28g . It is often convenient to express the masses of nuclei in terms of atomic mass units; 1u = 1.660540x10-24 g , exactly 1/12 the mass of the isotope carbon-12. The masses of nuclear particles are also frequently expressed in terms of their rest mass energies, in units of MeV. The simplest isotope of hydrogen is composed of one proton and one electron and has a mass of m H = 1.007825 u . This mass is actually less than the combined masses of the proton and electron taken separately. In fact, the exact mass difference is 13.6 eV if the atom is in its ground state, which is just its ionization potential. Since mass and energy are equivalent, and the total mass-energy of the system must be conserved, any loss in energy when the electron and proton combine to form an atom must come at the expense of a loss in total mass. This is the binding energy of the atom. The estimate of the nuclear timescale for the Sun was based on the assumption that four hydrogen nuclei are converted into helium. However, it is highly unlikely that this could occur via a four-body collision, i.e., all nuclei hitting simultaneously. For the process to occur, the final product must be created by a chain of reactions, each involving a much more probable two-body interaction. The process of nuclear reactions obey conservation laws, it is necessary to conserve electric charge, the number of nucleons, and the number of leptons “light thing” and includes electrons, positrons, neutrinos, and antineutrons”. Although antimatter is extremely rare in comparison with matter, it plays an important role in subatomic physics, including nuclear reactions. Antimatter particles are identical to their matter counterparts but have opposite attributes, such as electric charge. Antimatter also has the characteristic that a collision with its matter counterpart results in complete annihilation of both particles, accompanied by the production of energetic photons. For instance e e 2 , (4.23) 9 where e-, e+, and γ denote an electron, positron, and photon, respectively. Note that two photons are required to conserve momentum and energy simultaneously. Applying the conservation laws, one chain of reactions that can convert H to He is the first proton-proton chain (PP I). It involves a reaction sequence that that ultimately results in 4 11H 24 He 2e 2ve 2 . (4.24) Through the intermediate production of deuterium ( 12 H ) and helium-3. The entire PP I reaction chain is 1 1 H + 11 H ® 12 H + e + +v e 2 1 H 11H 23He 3 2 He 23He24 He 211H . (4.25) Each step of PP I chain has its own reaction rate, since different Coulomb barriers and cross sections are involved. The slowest step in the sequence is the initial one, occurring because it involves the decay of a proton into a neutron via p n e ve . Such a decay involves the weak force, another of the four known forces. The production of helium-3 nuclei in the PP I chain also provides for the possibility of their interaction directly with helium-4 nuclei, resulting in a second branch of the PP chain. In an environment characteristic of the center of the Sun, 69% of the time a helium-3 interacts with another helium-3 in the PP I chain, while 31% of the time the PP II chain occurs: 3 2 He 24He 47 Be 7 4 Be e 37 Li ve (neutrino) 7 3 Li 11H 2 24 He (4.26) Yet another branch, the PP III chain, is possible because the capture of an electron by the beryllium7 nucleus in the PP II chain is in competition with the capture of a proton (a proton is capture only 0.3% of the time in the center of the Sun): 7 4 Be 11H 58 B 8 5 Be ® 8 4 Be 2 24 He 8 4 Be + e + +v e (4.27) The three branches of the proton-proton chain, along with their branching ratios, are summarized in the figure. The nuclear energy generation rate for the combined PP chain is calculated to be 1 / 3 6 pp 2.38 x10 6 X 2 f pp ppC ppT62 / 3 e 33.80T 10 ergs g 1 s 1 (2.28) where T6 is a dimensionless expression of temperature in units of 106 K (or T6 T / 10 6 K), f pp = f pp (X ,Y , ,T ) 1 is the PP chain screening factor, pp = pp (X ,Y ,T ) 1 is a correction factor that accounts for the simultaneous occurrence of PP I, PP II, and PP III, and C pp 1 involves higher order correction terms. When written the previous equation as a power law near T=1.5x107 K, the energy generation rate has the form pp o¢, pp X 2 pp f ppT64 , (4.29) where o, pp 1.07x10 5 erg cm3g 2s 1 . The power law form of the energy generation rate demonstrates a relatively modest temperature dependence of T4 near T6=15. At tempertures below 20 million degrees the PP chain is the mail energy production mechanism. At higher temperatures corresponding to stars with masses above 1.5 M ๏, the CNO cycle becomes dominant, because its reaction rate increases more rapidly with temperature. A second independent cycle called CNO cycle also exists for the production of helium-4 from hydrogen. In the CNO cycle, carbon, nitrogen, and oxygen are used as catalysts, being consumed and then regenerated during the process. The first branch culminates with production of carbon-12 and helium-4: 12 6 C 11H 137N 13 7 N 136C e ve 13 6 N 11H 158O 15 8 O157N e ve 15 7 14 7 C 11H 147 N N 11H 126C 24He . (4.30) The second branch occurs only about 0.04% of the time, and arises when the final reaction in the previous equation produces oxygen-16 and a photon, rather than carbon-12 and helium-4: 15 7 N 11H 168 O 17 8 O 11H 147 N 24He . 16 8 O 11H 179 F 17 9 F 178 O e ve (4.31) The energy generation rate for the CNO cycle is given by 1 / 3 6 CNO 8.67x10 27 X X CNO CCNOT62 / 3e 152.28T ergs g 1 s 1 , (4.32) where XCNO is the total mass fraction of carbon, nitrogen, and oxygen and CCNO is a higher-order correction term. When written as a power law centered about T=1.5x107 K, the energy equation becomes 11 CNO o¢,CNO X X CNOT619.9 , (4.33) where o, CNO =8.24x10-24 erg cm3g-2s-1. Apparently the CNO cycle is much more strongly temperature-dependent than is the PP chain. This property implies that low-mass stars, which have smaller central temperatures, are dominated by the PP chains during their “hydrogen burning” evolution while more massive stars, with their higher central temperatures, convert hydrogen to helium by the CNO cycle. When hydrogen is converted into helium, by either the PP chain or the CNO cycle, the mean molecular weight of the gas will increase. If neither the temperature nor density of the gas changes, the ideal gas law predicts that the central pressure would necessarily decrease. As a result, the star would no longer be in hydrostatic equilibrium and would begin to collapse. This collapse has the effect of actually raising both the temperature and the density to compensate for the increase in . When the temperature rises by a factor of an approximately 64 above what is necessary to burn hydrogen, helium nuclei can overcome their Coulomb repulsion and begin to burn. The process becomes progressively more likely as the amount of helium increases. As a result of the preceding reactions, the abundance of helium increases in the stellar interior. At a temperature above 108 degrees the helium can be transformed into carbon in the triple alpha (4He) reaction. The reaction sequence by which helium is converted into carbon is known as the triple alpha process. The triple alpha process is 4 2 He 24He 48 Be 8 4 Be 24He 126C (4.34) In the triple alpha process, the first step produces an unstable beryllium nucleus that will rapidly decay back into two separate helium nuclei if not immediately struck by another alpha particle. As a result, this reaction may be through of as a threebody interaction and therefore, the reaction rate depends on (ρY)3. The nuclear energy generation rate is given by 1 8 3 5.09x1011 2Y 3 T83 f 3 e 44.02T ergs g 1 s 1 (4.35) where T8 = T/108 K and f3α is the screening factor for the triple alpha process. Written as a power law centered on T=108 K, it demonstrates a very dramatic temperature dependence, 12 3 o' ,3 2Y 3 f 3 T841.0 (4.36) With such a strong dependence, even a small increase in temperature will produce a large increase in the amount of energy generated per second. For instance, an increase of only 10% in temperature raises the energy output rate by more than 50 times! In the high temperature environment of helium burning, other competing processes are also at work. After sufficient carbon has been generated by triple alpha process, it becomes possible for carbon nuclei to capture alpha particle, producing oxygen. Some of the oxygen in turn capture alpha particle to produce neon. C 24 He 168 O 12 6 16 8 (4.37) O 24 He 1020 Ne At helium burning temperature, the continued capture of alpha particles leading to progressively more massive nuclei quickly becomes prohibitive due to the ever higher Coulomb barrier. Problem (6): Calculate the ratio of the energy generation rate for the PP chain to the energy generation rate for the CNO cycle given conditions characteristic of the center of the present –day (evolved) Sun, namely T=1.58x107 K, = 162 g cm-3, X= 0.34, and XCNO = 0.013. Assume that the PP chain screening factor is unity (fpp=1) and that the PP chain branching factor is unity (pp=1). 1 Problem (7): Beginning with the equation 3 5.09x1011 2Y 3 T83 f 3 e 44.02T8 ergs g 1 s1 and writing the energy generation rate in the form (T ) = ''T s , show that the temperature dependence for the triple alpha process, given by the equation 3 o' ,3 2Y 3 f 3 T841.0 is correct. ” is a function that is independent of temperature Hint: First take the natural logarithm of both sides of equation 1 8 3 5.09x1011 2Y 3 T83 f 3 e 44.02T ergs g 1 s1 and then differentiate with respect to ln T8. Follow the same procedure with your power law form of the equation and compare the results. You may want to make use of the relation d ln d ln d ln = = T8 1 d lnT 8 dT 8 dT 8 T8 13 2.4 Binding energy A mass of nuclei with several protons and/or neutrons does not exactly equal mass of the constituents “slightly smaller” because of the binding energy of the nucleus. Since binding energy differs for different nuclei, can release or absorb energy when nuclei either fuse or fission. Example: In the Sun 4x 1 H 4 He 4 protons, each of mass 1.0081 atomic amu: 4.0324 mass of helium nucleus: 4.0039 The mass difference is 0.0285 amu (atomic mass unit, 1 amu=1.6605402x10-24 g) which equal 4.7x10-26 g. So, E=Mc2 = 4.3x10-5 erg = 27 MeV. Energy yield ~ 10-5 erg per proton, so ~ 4x1038 reactions per second needed to yield L๏. About 650 million tones of hydrogen fusing per second. Generally calculation: define the binding energy of a nucleus as the energy required to break it up into constituent protons and neutrons. Suppose nucleus has proton number Z, atomic mass number A (number of protons+neutrons) and mass mnuc. Binding energy, Eb, will be given as: E b mc 2 [(A Z )m n Zm p m nuc ]c 2 . Most useful quantity in understanding the energy release in nuclear reactions is the binding energy per nucleon, Eb/A. Plot Eb/A versus A largely determines which elements can be formed in different stars. The general trend is an increase of Eb/A with A up to iron (A=56) and a slow monotonic decline beyond iron. The steep rise of the binding energy from hydrogen, through deuterium and 3He, to 4He implies that fusion of hydrogen into helium should release a large amount of energy per nucleon (unit mass), considerably larger than that released in, say, fusion of helium into carbon. It is apparent that for relatively small values of A (less than 56), several nuclei have abnormally high values of Eb/A relative to others of similar mass. Among these unusually stable nuclei are 24 He and 168O , which, along with 11 H , are the most abundant nuclei in the universe. Another important feature is the broad peak around A=56. At the top of the peak is iron, 56 26 Fe , the most stable of all nuclei. Most bound nucleus is iron 56: A less 14 than 56 fusion release energy, A larger than 56 fusion requires energy. Yield for fusion of hydrogen to 56Fe:~8.5 MeV per nucleon. Most of this is already obtained in forming helium (6.6 MeV). It is believed that shortly after this Big Bang the early universe was composed primarily of hydrogen and helium, with no heavy elements. Today Earth and its inhabitants contain an abundance of heavier elements. The study of stellar nucleosynthesis suggests strongly that these heavier nuclei were generated in the interiors of stars. It can be said that we are all “star dust” the product of heavy element generation within previous generation of stars. Based on stellar nucleosynthesis, it should come as no surprise that the most abundant nuclear species in the cosmos are, in order, 1 1 H , 24 He , 16 8 O, 12 6 C , 1020 Ne , 14 7 N , and 56 26 Fe . The abundances are the result of the dominant nuclear reaction processes that occur in stars, together with the nuclear configurations that result in the most stable nuclei. Problem (8): Calculate the rest energy of a proton in MeV. Problem (9): Calculate the binding energy of the deuteron, an isotope of hydrogen containing one proton and one neutron, given the following mp = 1.6726x1024 g, mn = 1.6749x1024 g, md = 3.3436x1024 g. Problem (10): Calculate the binding energy of a 4He nucleus. Problem (11): The Q value of a reaction is the amount of energy released (or absorbed) during the reaction. Calculate the Q value for each step of the PP I reaction chain. Express your answers in MeV. The masses of 12 H , and 23 He are 2.0141 u and 3.0160 u, respectively. Problem (12): Is the source of nuclear energy sufficient to power the Sun during its lifetime? For simplicity, assume also that the Sun was originally 100% hydrogen and that only the inner 10% of the Sun’s mass can be converted from hydrogen into helium. 15 Problem (13): Calculate the amount of energy released or absorbed in the following reactions (express your answers in MeV) (a) 126 C + 126 C ® 24 12 (b) 126 C + 126 C ® 16 8 (c) 19 9 Fe + 11 H ® The mass of Mg + O + 2 24 He 16 8 O + 24 He 12 6 C is 12.0 u, by definition, and the masses of 16 8 O, 19 9 F , and 24 12 Mg are 15.99491 u, 18.99840 u, and 23.98504 u, respectively. Are these reactions exothermic or endothermic? 16 Stellar model building We have now derived all of the fundamental equations of stellar structure. These equations, together with a set of relations describing the physical properties of the stellar material, may be solved to obtain a theoretical stellar model. The actual solution of the stellar structure equations and the consititutive relations requires appropriate boundary conditions that specify physical constrains to the mathematical equations. Boundary conditions essentially play the role of defining limits of integration. The central boundary conditions are fairly obvious, namely that the interior mass and luminosity must approach zero at the center of the star, or M r 0 Lr 0 as r 0 (4.38) A second set of boundary conditions is that the temperature, pressure, and density all approach zero at some surface value for the star’s radius, R*, or T 0 P 0 0 as r R * . (4.39) Finally, given the basic stellar structure equations, constitutive relations, and boundary conditions, we can now specify the type of star to be modeled. As can be seen the pressure gradient at a given radius is dependent on the interior mass and density. Similarly the radiative temperature gradient depends on the local temperature, density, opacity, and interior luminosity, while the luminosity gradient is a function of the density and energy generation rate. The density, opacity, and the energy generation rate in turn depend explicitly on the pressure, temperature, and the composition at that location. If the interior mass at the surface of the star (the entire stellar mass) is specified, along with the composition, surface radius, and the luminosity, application of the the surface boundary conditions allows for a determination of the pressure, interior mass, temperature and the interior luminosity at an infinitesimal distance dr below the surface of the star. Continuing this numerical integration of the stellar structure equations to the center of the star must result in agreement with the central boundary conditions. Since the values of the various gradients are directly related to the composition of the star, it is not possible to specify any arbitrary combination of surface radius and luminosity after the mass and composition have been selected. Similarly, if the mass, radius, and luminosity are specified, a unique composition structure is required. This set of 17 constrains is known as the Vogt-Russell theorem: “The mass and composition of a star uniquely determine its radius, luminosity, and internal structure, as well as its subsequent evolution.” With the exception of very special solutions to the stellar structure equations, the system of differential equations, along with their constitutive relations, cannot be solved analytically. Instead, as already mentioned, it is necessary to integrate the system of equation numerically. This is accomplished by approximating the differential equations by the difference equations, by replacing dP/dr by P/r, for instance. The star is then imagined to be constructed of spherically symmetric shells and the integration is carried out from some initial radius in finite steps by specifying some increment δr. It is the possible to increment each of the fundamental physical parameters through successive applications of the difference equations. For instance, if the pressure in zone i is given by P, then the pressure in the next deepest zone, Pi+1, is found from Pi 1 Pi P r, r (4.40) where δr is negative. The numerical integration of the stellar structure equations may be carried out from the surface towered the center, from the center towered the surface, or, as is often done, in both directions simultaneously. If the integration is carried out in both directions, the solutions will meet at some fitting point where the variables must vary smoothly from one solution to the other. The last approach is frequently taken because the most important physical processes in the outer layers of stars generally differ from those in the deep interiors. The transfer of radiation through optically thin zones and the ionization of hydrogen and helium occur close to the surface while nuclear reactions occur near the center. By integration in both directions, these processes may be decoupled somewhat, simplifying the problem. A very simple stellar structure code (called STATSTAR), written in FORTRAN, integrates the stellar structure equations developed in this chapter in their time-dependent form from the outside of the star to the center using appropriate constitutive relations; it also assumes a constant (or homogenous) composition throughout. So that the basic elements of stellar model building can be more easily understood, many of the sophisticated numerical techniques present in research codes have been neglected, as have the detailed calculations of the pressure equation of state and the opacity. Despite these approximations, very reasonable models may be obtained for stars lying on 18 the main sequence of the H-R diagram. An example of 1 M๏ star is given in Appendix I to help the student interpret the output of STATSTAR. ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------Solve computer problems 10.18, 10.19 and 10.20, page 378-388. 19