Family-centred, child-focused support in the early childhood years

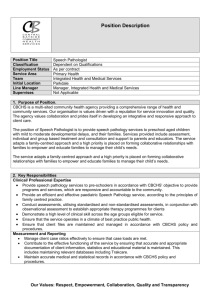

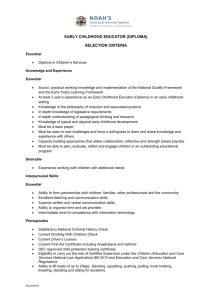

advertisement