DNA Databases for Law Enforcement

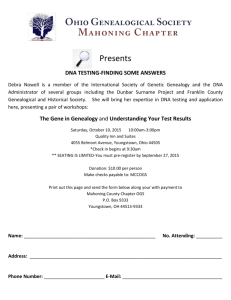

advertisement