Resource 2 - Zoo and Wildlife Solutions

advertisement

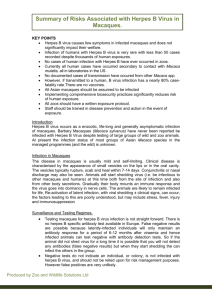

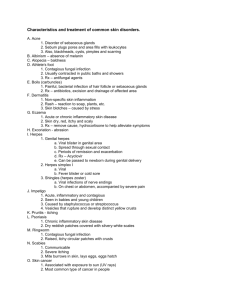

Old World Monkey Taxon Advisory Group Veterinary Advice Herpes B Virus Produced by Matt Hartley, Yedra Feltrer & Stephanie Sanderson with significant contribution from guidance produced by Larry Vogelnest and David McLelland of the Zoo & Aquarium Association, Australasia. Introduction Herpes B virus occurs as a enzootic, life-long and generally asymptomatic infection of macaques (Macaca spp.). Macaca genus monkeys are native to North Africa and Asia. Many thousands of macaques are maintained around the world in zoos, laboratories, circuses and private homes, making the distribution of the virus virtually worldwide. All Macaca spp. should be assumed to be hosts for herpes B virus. (It should be noted that Herpes B has never been demonstrated by virus isolation or serology in Macaca sylvanus (Barbary Macaque)). The main risk associated with maintaining captive macaques potentially infected with Herpes B virus is the risk of transmission to humans because if a human becomes infected with the virus it is likely to be fatal. Herpes B virus rarely causes significant disease in macaques and compromises welfare minimally. At present the infection status of most groups of Asian Macaca species in the managed programmes (and the wild) is unknown. This is partly due to the difficulty in accessing and interpreting the diagnostic tests and also the fear that government authorities may require the euthanasia of infected animals. Basic characteristics of primate herpes viruses: Herpes B virus (also known as herpes simiae, monkey B virus and Cercopithecine herpesvirus 1) is one of a large group of primate alpha herpes viruses, many of which are transmissible between different primate species. Alpha herpes viruses are usually of low pathogenicity (i.e. cause minor or no disease) in their natural hosts, only causing serious disease in aberrant (unnatural) hosts. The alpha herpes viruses endemic in most human populations are Herpes simplex 1 & 2 (causing cold sores and genital herpes respectively). These generally cause minor of no disease in humans yet can be fatal to callitrichidae. Herpes B can be thought of as the ‘herpes simplex’ of macaques. Species affected by Herpes B virus. All Asian macaque species are thought to be susceptible to Herpes B virus infection. Rhesus (M.mulatta) and cynomolgus (M. fascicularis) macaques are the most commonly reported species infected with herpes B however virus has also been isolated from stumptailed (M. arctoides), pig-tailed (M. nemestrina), Japanese (M.fuscata), Bonnet (M. radiata), and Taiwan (M. cyclopis) macaques. The status of Sulawesi crested macaque (M. nigra) and lion tailed macaque (M. silenus) is unknown – however anecdotal evidence (via AZA OWM TAG) suggests that these have tested positive. At least 3 genetically different strains of herpes B virus have been detected. -1- Research is limited however the different species of macaque appear to carry different strains. These strains have been shown to have different virulence. The strain carried by Rhesus macaques is thought to be the most virulent to humans. The prevalence of Herpes B infection in both wild and captive macaques is largely unknown. This due to few laboratories having the test specific for herpes B and limited research. Where population studies have occurred, if infection is present in the group, approx. 25% of juveniles are infected and 100% adults producing an overall infection rate of approx. 80%. (This data is for Rhesus and cynomolgus macaques in both laboratory and wild situations.) Because the virus is dormant in most infected monkeys only a very low percentage (2%–3%) will actually be infectious at any one time. No other monkey species are known to act as carriers for the herpes B virus. However, infection with associated disease and mortality has been reported in patas monkey (Erythrocebus patas), black and white colobus (Colobus guereza), capuchin monkey (Cebus apella), common marmoset (Callithrix jacchus), De Brazza monkeys (Cercopithecus neglectus), Barbary macaques (M sylvanus) and humans. Infection in primate species (including humans) other than macaques is usually fatal. Signs typically include classic herpes vesicles on the nares, oral cavity and conjunctiva, respiratory disease, menigoencephalits and high mortality rate. Transmission Herpes B virus is transmitted through biting and scratching (saliva, blood), and by fomites (inanimate objects such as cage furniture, utensils soiled with body fluids etc) and needle sticks and sharps. The virus can also cross intact mucous membranes (ie splashes of infected material into the eye can result in infection). Sexual transmission between macaques is thought to be the primary mechanism of transmission in established captive colonies. Primary infection in captive macaques usually occurs in juvenile animals as they lose their maternal antibodies, or in new arrivals. When a macaque becomes infected the virus multiplies up in the tissues at the site of infection. At this time the animal may show a rash/cold sore type lesion. Animals will start shedding virus (ie be infectious to others) at this time both from the site of infection and also from other body secretions. These animals will test negative by antibody tests but still be infectious. Gradually their body mounts an immune response and the virus goes into dormancy in nerve cells. These animals will now test positive by antibody test and are likely to remain infected for life. Whilst dormant no virus particles are shed (ie the animal is not infectious). Virus can be isolated in all body secretions from animals that are shedding (e.g. saliva, urine, tears) but not from animals where the virus is lying dormant. B virus is rarely found in the blood and transmission is very unlikely by this route. -2- Re-activation of latent infection, with viral shedding ± clinical signs, can occur; the factors leading to this are poorly understood, but may include stress, fever, injury and immunosuppression However, infected macaques exposed to such factors do not necessarily shed virus. When re-activation does occur, virus can potentially be shed in saliva, blood, faeces, and urine. Macaca sp. that are shedding the virus may be asymptomatic or have lesions similar to cold sores in humans and occasionally nasal discharge and conjunctivitis. These usually resolve spontaneously. Stress will increase the likelihood that the virus will be reactivated and shed. Minimising stress in a colony of macaques is critical. Measures to minimise stress include provision of an appropriate environment, behavioural enrichment, optimal nutrition, preventative medicine, breeding and genetic management (maintain the size and social structure of the colony to ensure harmony within the colony, and genetic management to reduce inbreeding). Disease in macaques Many colonies of macaques have endemic herpes B virus infection with no apparent impact on the general health of the animals. Prevalence of virus shedding at any given time is typically very low (2-3%), even in colonies where all animals carry the virus.. The disease in macaques is usually mild and self-limiting. Clinical disease is characterised by the appearance of small vesicles on the lips or in the oral cavity. The vesicles typically rupture, scab and heal within 7-14 days. Conjunctivitis or nasal discharge may also be seen. Fatal infection occurs rarely in macaques. Herpes B virus particles have been recovered from saliva, blood, faeces, urine, serum, eye, brain, genital tracts and kidney tissue cultures from infected macaques. Herpes B virus management in macaques Testing macaques for herpes B virus infection is not straight forward. Available diagnostic tests include antibody detection (for alpha herpesviruses), antigen detection, viral culture, and PCR. These tests can be used to detect infection in individuals or in colonies. There is no herpes B specific antibody test available in Europe. The used serological tests all cross react with other alpha herpesviruses. Additionally the potential for false negative results is the most problematic aspect of interpreting herpes B virus tests because latently-infected individuals will only maintain an antibody response for a period of 6-12 months after viraemia and hence infected animals can test negative with antibody detection tests. So if the animal did not shed virus for a long time it is possible that you will not detect any antibodies (false negative results) but when they start shedding they can infect the others in the group. Negative tests do not indicate an individual, or colony, is not infected with herpes B virus, and should not be relied upon for risk management purposes. False negative results are most problematic when testing one-off samples. Therefore it is recommended to perform multiple testing at least 3 times spread over a 6-12 month period -3- False positives are very unlikely. Herpes B virus management in EEP Programmes for Sulawesi Crested Macaque and Lion-Tailed Macaque There are two EEP programmes for macaque species managed by the Old World Monkey TAG. There are no reports of Herpes B in either Sulawesi Crested Macaque or Lion Tailed Macaque in the wild. There has been a single report of Herpes B in Lion Tailed Macaques in a zoo the USA but no confirmed reports of the virus being isolated from Sulawesi Crested Macaques in zoos. If the current EEP populations are infected the virus could have originated from wild caught animals (if Herpes B is endemic in wild populations) or from other macaques species housed in zoos which are known to harbor the virus. There is potential that the populations or individual groups have never been exposed to the virus and we have potential to maintain virus free populations, which would significantly reduce the risk of managing this species in zoos. The TAG has provided this comprehensive guidance for managing the risks associated with Herpes B in other macaque species in European zoos but makes no recommendations for monitoring or diagnostic testing for these species, which is left to the discretion of the individual zoos. Benefits of Testing EEP Macaques for Herpes B Virus An improved understanding of the prevalence and epidemiology of the virus in the EEP populations. Reassurance to zoo managers and staff that the status of the group is known positive so effective and comprehensive management plans can be implemented rather than working with animals of unknown status. A managed screening programme according to the guidelines below may satisfy decision makers that the likelihood the group is infected is lower and therefore the risks associated with import of the species is acceptable. An attempt can be made to establish groups, which repeatedly test negative but they cannot be classed as a negative group. The TAG can make an informed decision as to whether or not to require euthanasia of macaques which test positive for Herpes B virus. Consequences of Testing EEP Macaques for Herpes B Virus Public Health Authorities may require euthanasia of known positive individuals or groups. Zoo managers may insist on euthanasia of animals. Zoos may refuse to pay for diagnostic testing of animals. Zoos may refuse to hold groups that have tested positive for virus Governments may refuse to allow the import of macaques species into their countries. Other regional zoo associations may refuse to accept EEP animals. Governments may refuse to accept animals from zoos in any conservation reintroduction programmes for the species. -4- Wild populations may be endemically infected with Herpes B and therefore the status of EEP populations reflects the wild situation and the efforts have been pointless. Potential screening programme for EEP species If the TAG did decide to begin a screening programme the following protocol should be followed. Pre-export testing should be performed. This is no guarantee that the animal is not in the early stages of infection and is still potentially infectious but it will decrease the risk. Collections holding the EEP species should establish the infection status of the group. This should be done by opportunistic screening of adult animals. Most testing relies on looking for antibody levels in macaques. Most human laboratories can do a generic test for alpha herpes viruses (the human herpes simplex virus test cross reacts with herpes B virus). Samples from animals that are positive on this generic test should be submitted for specific Herpes B testing at a specialist laboratory. If any positive results are received the group should be considered known positive and managed accordingly. Multiple testing should be performed. - 4 serological tests period initially then at 6 weeks, 6 months and 12 months. When all tests come back negative, one can consider the individual animal non-infected but the tests will need to be repeated every 12 months. This is likely to be unfeasible in most zoo situations. All macaque deaths should be thoroughly investigated. Necropsies should be carried out by an experienced veterinarian or pathologist. Personal protective equipment (including gloves, masks, eye protection, protective clothing and footwear) should always be worn. The necropsy should preferably be carried out in a biohazard safety cabinet. Zoos which are unable to meet sufficient biosecurity standards for necropsy of macaques should consider submitting the body to an appropriate diagnostic laboratory. Laboratory personnel handling secretions, excretions, bodily fluids, and tissues from macaques Zoos undertaking diagnostic testing should discuss their testing regimes and protocols with the OWM TAG Vet advisors before commencing and should inform the vet advisors of all results. -5- Routine Herpes B Screening Standard Herpes Screening at Local Facility Negative Positive Send to Specialist Laboratory for Specific Herpes B Testing Tested Negative at that point in time. Repeat Negative Report to Local Health Authorities Test All Animals in Group Positive Inform EEP for Advice Euthanase Positive Animals Zoonotic potential and significance in man Transmission to humans is by contamination of wounds or mucous membranes with body secretions or tissues from infected animals. Currently all human cases have occurred secondary to contact with Macaca mulatta, all in a laboratory setting in the US. No documented cases of transmission have occured from other Macaca sp. Infection of humans with Herpes B virus is very rare. To date, <50 human infections have been reported in the literature since infection was first recognized in 1932, despite the thousands of exposures occurring both among laboratory workers and people exposed to free ranging macaques. However, if transmitted to a human, B virus infection has a nearly 80% casefatality rate and of before improved treatment regimes were instituted in 1987 many of those that survived had such severe brain damage that they required lifelong institutionalisation. B-virus disease in humans usually results from macaque bites or scratches Incubation periods may be as short as 2 days, but more commonly are 2 to 5 weeks. Length of incubation depends on the site of infection. Wounds to the head, neck and torso have much shorter incubation periods that wounds to the extremities. Vesicles on the skin develop at the site of inoculation 1–5 days post exposure in many cases, followed by swelling of local lymph nodes. Itchy skin and pain at the inoculation site may be intense. Other signs of infection include influenza like symptoms, such as persistent fever, headache, nausea, vomiting, and muscle pain. The disease progresses quickly to a fulminating meningoencephalitis. Symptoms include paralysis (often progressive and ascending), numbness dizziness, double vision, difficult swallowing and confusion, respiratory difficulties, urinary retention, -6- altered consciousness, and coma. The few cases that have been treated by the time neurologic symptoms have emerged have had limited success. Death occurs 10–14 days post exposure in 70–80% of herpes B virus infected humans, principally due to severe encephalitis. Latent infections can develop with subsequent reactivation. In recent years the case fatality rate has declined, likely due to the early initiation of antiviral therapy, better supportive care, and/or earlier diagnosis of infections. Minimising exposure risk to humans All macaques should be considered as potentially infectious regardless of any test results. No protective vaccines are available and treatment, though improving is not currently very successful. Control of Herpes B infection in humans must therefore be centred on prevention of exposures and good education of staff: Institutions should identify and collaborate with a local medical practitioner for establishing policy and protocols, and coordinating the response to an exposure event. All personnel should receive appropriate training on the risk associated with herpes B virus, appropriate methods of restraint, and the use of protective clothing. Regular staff refreshers should be conducted and a training and awareness log should be maintained to document that personnel have completed such requirements. Personnel should be required to sign that they acknowledge comprehension of institutional guidelines. Access to macaque areas should be restricted to people that have completed this process. Periodic reviews of safety procedures with regard to herpes B virus should occur. All personnel, including contractors, students and volunteers, that may be exposed to macaques, to their excretions/secretions, or may enter the macaque exhibit, should be fully briefed on the risk management guidelines for the prevention of herpes B virus and should read and understand the written protocols. Zoo employees should minimise direct and indirect contact with macaques, and do not enter enclosures containing macaques. Macaques should not be utilised for direct contact experiences for the general public, and that incidental contact of the general public with macaque body fluids (eg urine, spitting, throwing faeces) is prevented. Personnel coming into contact with macaques or their biological products should wear appropriate clothing that minimises the risk of contamination of skin and mucous membranes (e.g. eyes, mouth) with macaque secretions or excretions, and prevents scratches. This should include (at a minimum) longsleeved and long-legged garments, and sturdy slip-resistance footwear. Additional PPE may be considered based on a risk assessment of individual -7- facilities and work practices. Personal protective clothing and equipment should be supplied and laundered by the employer. Strict personal hygiene is essential for herpes B virus risk management. Hand washing is the most effective means of preventing transmission of zoonotic diseases generally. Disposable gloves should be used in higher risk situations, but they do not negate the importance of hand washing after working around macaques, or after servicing areas potentially contaminated by macaques. The use of high pressure hosing in macaque areas should be avoided to minimise the production of aerosols from faeces, saliva and other secretions/excretions. When cleaning exhibits, as much solid material as possible (faeces, food, bedding) should be picked up, using such as a broom and shovel, to minimise the need for hosing. Herpes viruses have limited abilities to withstand environmental conditions outside a host animal. Under optimal conditions, the virus can remain viable for up to 7 days at 37°C, and for several weeks at 4°C. Viability on dry surfaces has not been evaluated, but is likely similar to that of other mammalian herpesviruses: typically 3–6 hours. Herpes B virus is readily destroyed by common detergents and disinfectants; these should be used when cleaning enclosures and associated equipment. Common disinfectants (e.g. F10, Virkon, Trigene, Chlohexidine, bleach) at concentrations and contact times effective against other enveloped viruses, can reasonably be assumed to effective, though controlled trials have apparently not been conducted. Direct handling of macaques should be minimised. Capturing, restraining or otherwise handling fully conscious macaques is not recommended. Macaques should be physically restrained in a squeeze-cage and hand injected with a chemical restraint agent prior to handling. If a squeeze cage is not available, if an animal will not enter the squeeze system, or if an animal escapes the enclosure, chemical restraint via dart, or physical restraint in an appropriate net, may be necessary. Only experienced personnel wearing appropriate PPE should attempt physical capture of macaques. When physically restraining animals, particularly if not chemically restrained arm-length reinforced leather gauntlets should be worn. When handling chemically restrained animals, latex gloves and face protection should supplement standard PPE. Behavioural conditioning of macaques is a practical and very useful technique to complement physical and chemical restraint options. All veterinary procedures on macaques should be carried out by suitably experienced and competent veterinarians with a full understanding of herpes B risk and risk management. Veterinary procedures should only be performed on animals that are sufficiently chemically restrained. Protective clothing should be worn when handling macaques. Special care must be taken to prevent needle stick and other sharps injuries. Double gloving is recommended, especially for surgery. Masks and eye protection should be used for endotracheal intubation and other oral procedures to protect against -8- exposure to aerosolised secretions. Veterinary staff handling surgical packs, drapes, swabs, and other equipment used for macaque surgery should wear disposable gloves. The awareness of this infection should be increased amongst health care professionals and field workers in countries where Herpes B infection is endemic in the indigenous macaque population – It might be possible that many cases may go undiagnosed and hence untreated. Institutions should ensure suitable education and training programs for staff on any field programmes they support. Post exposure prophylaxis and first aid Humans should be considered as potentially exposed following any wound received from a macaque or contamination of mucous membranes or broken skin by macaque excretions and secretions. The adequacy and timeliness of wound decontamination procedures are the most important factors in preventing the risk of infection after herpes B virus exposure. Immediately after the exposure event: Skin wounds Cleanse the exposed area by thoroughly washing and scrubbing the area or wound with povidone-iodine surgical scrub, chlorhexidine surgical scrub, soap, or concentrated detergent, for 15 minutes Then: Irrigate the washed area with running water for 15-20 minutes. Mucous Membranes (eyes, mouth etc) Irrigate the area for 15-20 minutes with saline or running water. (soap, detergent and disinfectants are too harsh for application to the eye or other mucous membranes) As soon as possible following first aid procedures the patient should receive medical attention, ideally by the zoo’s identified medical practitioner who has been involved in developing institution specific protocols. Information sheets containing basic information about herpes B virus, postexposure treatment protocols, and contacts for further information should be readily accessible and accompany the patient to the medical facility. The identified medical practitioner(s) may be unavailable at the time and the patient could be seen by a doctor unfamiliar with herpes B virus. Without delaying first aid, the details of the events associated with exposure should be documented, including the time of exposure, the nature of the exposure, the location of any injuries, the identification of the macaque(s) involved, the first aid measures administered and who administered them. This information assists the examining physician to determine the relative risk of B virus exposure, and allows for modification of existing protocols to prevent similar exposure events in the future. -9- The clinical and virological status of a macaque at the time of a human exposure event may provide information useful to the medical practitioner. The decision to assess a macaque for herpes B virus-associated lesions and/or collect samples for virus detection should be made by the zoo veterinarian(s) in consultation with the medical practitioner. A risk assessment should be carried out as soon as possible post-exposure based on the realistic and predictive values of testing the macaque(s) and further operator risk. Swabs collected for virus detection will be most useful if collected as close to the time of exposure as possible; swabs collected at a later time may not accurately reflect the macaque’s status at the time of the exposure. The macaque should be anaesthetised for any such procedure, to facilitate safe and thorough examination and sample collection. Samples from the macaque that may be considered for viral screening include: Serum samples collected at the time of human exposure, and 14-21 days later Swabs from buccal cavity (inside the cheek), right eye, left eye and genitalia. Swabs should be placed immediately into viral transport medium. Use a separate swab for each site. If the specific macaque associated with the injury is unknown, the value of testing all animals in the group is generally considered to be low. References Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), Govt USA. Herpes B virus website: http://www.cdc.gov/herpesbvirus/index.html Guidelines for the prevention of Herpesvirus simiae (B virus) infection in monkey handlers. MMWR 1987;36:680-2, 687-9. http://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/00015936.htm European Association of Zoo and Wildlife Veterinarians (EAZWV). Transmissible Disease Fact Sheet: B-Virus. http://www.eaza.net/activities/tdfactsheets/009%20BVirus.doc.pdf American Association of Zoo Veterinarians (AAZV). 2013. Infectious Disease Committee Manual: Herpesvirus B. http://c.ymcdn.com/sites/www.aazv.org/resource/resmgr/IDM/IDM_Herpes_B_2013.p df Cohen JI, DS Davenport, JA Stewart, S Deitchman, JK Hilliard, LE Chapman, and the B Virus Working Group. 2002. Recommendations for prevention of and therapy for exposure to B virus (Cercopithecine herpesvirus 1). Clinical Infectious Diseases. 235: 1191–1203. Huff JL, Barry PA. (2003) B-virus (Cercopithecine herpesvirus 1) infection in humans and macaques: potential for zoonotic disease. Emerg Infect Dis Vol.9 (2) 246-250. CDC Herpes B fact sheet: http://www.cdc.gov/herpesbvirus/index.htm Engel GA, Jones-Engel L, Schillaci MA, Suaryana KG, Putra A, Fuentes A, Henkel R. (2002) Human exposure to herpesvirus B-seropositive macaques, Bali, Indonesia. Emerg Infect Dis. 2002 Aug;8(8):789-95 Jensen K, Alvarado-Ramy F, González-Martínez J, Kraiselburd E, Rullán J. (2004) B virus and free-ranging macaques, Puerto Rico. Emerg Infect Dis. 2004 - 10 - Mar;10(3):494-6 Bielitzki JT. (1999) Emerging viral diseases of nonhuman primates. In: Fowler ME, Miller RE, editors. Zoo and wild animal medicine: Current therapy 4. Saunders, Philadelphia, pp 377-382. Loomis MR, O’Neill T, Bush M, Montali RJ. (1981) Fatal herpesvirus infection in Patas monkeys and a Black and White Colobus monkey. Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association. 179:1236–1239. Reme T et all (2009) Recommendation fro post-exposure prophylaxis after potential exposure to herpes b virus in Germany. J Occup Med Toxicol. 4:29. - 11 -