The Middle Ages: An Introduction

advertisement

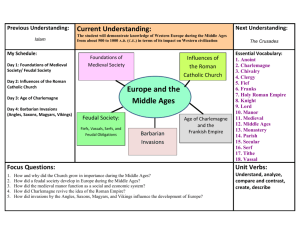

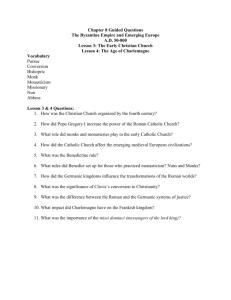

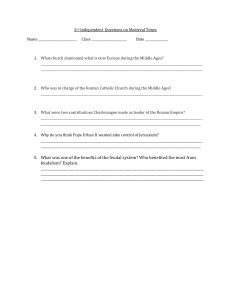

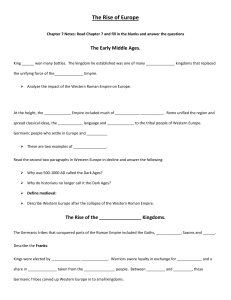

The Early Middle Ages Questions: 1. Identify the time periods of the Early, High, and Late Middle Ages. Answer: 2. Maps: visit the map web links on p. 2 and answer the questions in the text. Answer: 3. Legacy of Charlemagne: visit the web link (p. 2) assess his historical significance. Answer: 4. Why did it become so difficult to maintain centralized government under a single king in the last two centuries of the Early Middle Ages? Answer: 5. Interpreting visual evidence: explain the illustration of feudal society on p. 3. What visual clues identify the people in the illustration? Answer: 6. Visit the Medieval manor web link (p. 3) and answer the questions in the text. Answer: 7. Visit the Medieval scriptorium web link (p. 4) and answer the question in the text. Answer: 8. Understand the main idea of each section; note the significance of items in bold The Middle Ages, roughly from A.D. 500 to 1500, marked a new beginning for Western history. The Roman Empire had been undergoing a process of gradual decline from the end of the Pax Romana in A.D. 180, and the western half of the Roman Empire had dissolved by the fifth century as a result of both internal and external pressures. Over the next 500 years during the Early Middle Ages, Western peoples returned to simple agricultural villages and turned to local land-owning lords for protection. Then, over the next 500 years during the High and Late Middle Ages, Westerners slowly learned to rebuild cities, revitalize trade, and construct larger political units as nation-states developed, especially in western Europe. Europe began to develop economically and technologically and constructed a sophisticated culture that set the stage for Europe dramatic development in the modern era. The Early Middle Ages Traditional histories of the origins of the Middle Ages used to begin with images of “barbarian” invaders suddenly sweeping into western Europe and destroying the Roman Empire virtually overnight. These depictions tended to be interestingly dramatic but very exaggerated. More recently, historians have abandoned this simple story line. Instead of a sudden “fall” of Rome in the fifth century and an equally sudden 1 beginning of the Middle Ages in 476 (the year Germanic invaders overthrew the last Roman emperor of the Western Empire), we now think of a gradual transition. Rome and its culture did not disappear overnight. In fact it took centuries for various Germanic peoples to migrate into Europe during “Late Antiquity” (300s-400s) and to change it. The West underwent a period of gradual transformation – a slow blending of Roman civilization, Germanic culture, and Christianity. Map-links: These links show the growth of the Roman Empire and the intrusion of invaders from the north and the east. Map-A Question: Who were the Germanic invaders who were the first to threaten the Roman Empire from the north? http://nersp.nerdc.ufl.edu/~malavet/com parat/notes/romanmap.gif Map-B Question: Contrast the Eastern and Western halves of the Empire: which was threatened more by invasion? http://www.zonu.com/images/0X0/200912-09-11393/Barbarian-invasions-ofthe-Roman-Empire-100-to-500.png Political Organization in the Early Middle Ages Political organization during the Early Middle Ages falls into two phases: 500-800: attempts to organize Germanic kingdoms in the old Roman Empire. 800-1000: full development of “feudalism.” After the gradual decay of the Roman Empire, medieval people had to organize new ways to establish power and order. Germanic invaders began a process of organizing smaller “kingdoms” in place of the larger, “centralized government” of the Roman Empire (government from a single center of power, a capital city). These early Germanic kingdoms were very loosely organized in contrast to the highly centralized government of the Roman Empire at its height. The most successful of these early kingdoms was established in the old Roman province of Gaul (modern-day France)—the “kingdom of the Franks,” which developed after 500 and reached its height under the Frankish king Charlemagne around 800. Charlemagne—Charles the Great— reigned for nearly fifty years, carving out an impressive kingdom by conquest and through close association with the Church. Peace terms imposed by Charlemagne often included the requirement to convert to Christianity. For these and other services to the Church, Pope Leo III crowned Charlemagne “Emperor of the Romans” on Christmas Day, 800. Map-C Question: Charlemagne’s Kingdom: how does it compare with the Roman Empire at its height? http://www.laughtergenealogy.com/bin/h istprof/images/europe_map.gif Maintaining centralized control of his kingdom was difficult, and Charlemagne followed the Germanic custom of granting regional authority to local lords, exchanging control of land for soldiers to serve in the king’s army. Charlemagne maintained a corps of royal officials called missi dominici, who checked up on local lords and reported back to the king. Charlemagne sponsored an impressive cultural revival often referred to as the “Carolingian Renaissance,” attracting scholars to his capital at Aachen, 2 encouraging reforms to the teaching of Churchmen, and establishing a Palace School to educate royal officials. Scholars copied and preserved ancient manuscripts, ensuring their survival. Web Link Question: Legacy of Charlemagne: What is his long-term historical significance? http://www.themiddleages.net/people/ch arlemagne.html After Charlemagne’s death, his kingdom dissolved under the pressure of a second wave of invasions in the ninth century. From the north, the Vikings or Northmen swept down from Scandinavia. From the south Muslim invaders known as the Moors had invaded Spain and the islands of the Western Mediterranean and continued their attacks on the West. As a consequence of this new chaos, political power fell into the hands of local land-controlling lords who had only a limited personal allegiance to more powerful nobles or to distant “kings” who were kings in name only. The political system of feudalism developed in this setting. Feudal society Feudal Social Structure The social structure of early medieval society was organized around three groups of people who provided society’s basic services and functions: lords— those who fought and controlled the land; religious—those who prayed; serfs—those who worked. Serfs were peasant farm workers legally tied to the lands of their lords. Small numbers of freemen did exist and provided essential craft services, but this group was small in the early medieval period. Society was relatively static: social position was fixed as part of God’s divine plan for the universe. Economic Reorganization The early medieval period—once referred to as the “Dark Ages”—was a time of slow growth, when the West was a relatively unhttp://www.laughtergenealogy.com/bi n/histprof/images/europe_map.gifderdev eloped part of the globe. For the most part, Western Europe was cut of from trade with other parts of the world. In a world without trade, people had to provide for themselves. An economic system called manorialism developed in this economic context. The goal of the manorial economic system was to provide virtual selfsufficiency in a world in which very little was coming in from the outside. It is important to remember that manorialism did succeed in meeting the basic economic needs of society and represented a process of cultural adaptation to changing times and problems. Web Link Questions: Medieval manor: How self-sufficient was the 3 manor? What was the purpose of a fallow field? http://go.hrw.com/hrw.nd/gohrw_rls1/p KeywordResults?keyword=st9%20medi eval%20manor Cultural Life These political, social, and economic arrangements seem rather primitive when compared with the sophisticated culture of the classical world of Greece and Rome. It is important to remember that Western Europe was in “survival mode,” trying to hang on in the face of not one but two periods of chaotic invasion. Pervasive, but gradual cultural decline characterized Western Europe in the early medieval period. Urban life, formal schooling, literacy (all the markers of “high” civilization) had—not quite, but almost—vanished for most people. A Medieval Scriptorium During the early medieval period great lords—even kings—were mostly illiterate. Even the great Charlemagne could read but never mastered the ability to write. Only the clergy retained the ability to read and write, and the only schools were located in monasteries and were dedicated to teaching religious not ordinary people. Because monks had to be literate to read the Holy Scripture, monasteries became centers of learning: manuscripts were preserved and copied there. Web Link Question: a medieval scriptorium: How long would it take to hand-copy the bible? http://www.hrc.utexas.edu/exhibitions/p ermanent/gutenberg/html/2.html Literate monks such as St. Bede in England (author of The Church History of the English Nation) and Gregory of Tours (author of the History of the Franks) wrote some of the few surviving histories of the early Middle Ages. It would be wrong to think of this world as culture-less. Recent historians have emphasized the efforts to preserve civilization and the emergence of a new medieval synthesis—a culture that combined Roman, Germanic, and Christian elements. An illiterate German warrior class replaced an educated Roman aristocracy, and a vigorous oral literature, now largely lost, was sung or chanted in the halls of Europe’s new Germanic rulers. Little of this was written down in a society where few could read. From Britain, however, came one great epic story: Anglo-Saxon tale of Beowulf dating from the seventh or eighth century. Almost everything about the poem is debated by scholars, but the story itself, of the hero Beowulf’s killing, first, of the monster Grendel and then of Grendel’s even more ferocious mother, suggests something of the primitive violence of early medieval society. 4 The Middle Ages, then, is not just about decline and decay and “darkness.” In the disintegration of the older Roman Empire a distinctive, new “medieval” society—a blend of late Roman culture, Germanic traditions, and Christianity— grew. CLASS NOTES: 5