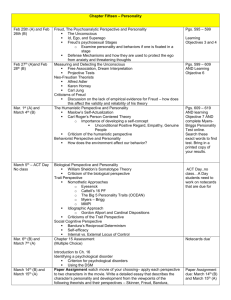

Personality

advertisement

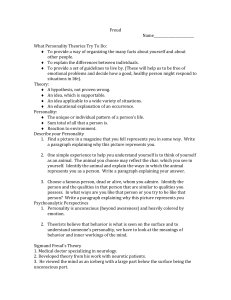

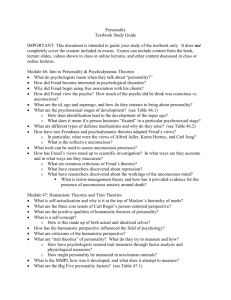

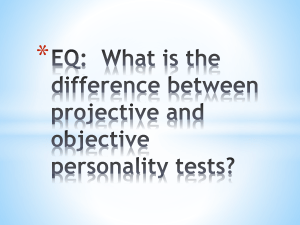

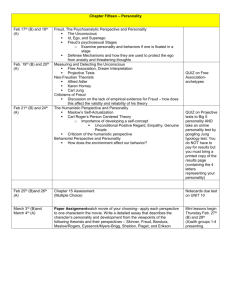

PERSONALITY CHAPTER OBJECTIVES 1. Describe what is meant by personality, and explain how Freud’s treatment of psychological disorders led to his study of the unconscious. 2. Describe personality structure in terms of the interactions of the id, ego, and superego. 3. Identify Freud’s psychosexual stages of development, and describe the effects of fixation on behavior. 4. Explain how defense mechanisms protect the individual from anxiety. 5. Explain how projective tests are used to assess personality. 6. Discuss the contributions of the neo-Freudians, and describe the strengths and weaknesses of Freud’s ideas. 7. Discuss psychologists’ descriptions of personality in terms of types and traits. 8. Explain how personality inventories are used to assess traits, and discuss research regarding the consistency of behavior over time and across situations. 9. Describe the humanistic perspective on personality in terms of Maslow’s focus on self-actualization and Rogers’ emphasis on people’s potential for growth. 10. Describe humanistic psychologists’ approach to personality assessment, and discuss the benefits and liabilities of self-esteem and self-serving bias. 11. Describe the impact of individualism and collectivism on self-identity and social relations. 12. Discuss the criticisms of the humanistic perspective. 13. Describe the social-cognitive perspective on personality, and explain reciprocal determinism. 14. Discuss the important consequences of personal control, learned helplessness, and optimism. 15. Describe how social-cognitive researchers assess behavior in realistic situations, and evaluate the social-cognitive perspective on personality. INTRODUCING PERSONALITY Psychologists consider personality to be one’s characteristic pattern of thinking, feeling, and acting. If your behavior pattern is strikingly distinctive and consistent, people are likely to say you have a “strong” personality. In the course of their work, personality theorists address fundamental issues of human nature and individual differences. Some of these issues may include: * 1. Free will or determinism? Do we have a conscious awareness and control of ourselves? Are we free to choose, to be masters of our fate, or are we victims of biological factors, unconscious forces, or external stimuli? 2. Nature or nurture? Is our personality determined primarily by the abilities, temperaments, or predispositions we inherit, or are we shaped more strongly by the environments in which we live? 3. Past, present, future? Is personality development basically complete in early childhood? Or is personality independent of the past, capable of being influenced by events and experiences in the present and even by future aspirations and goals? 4. Uniqueness or universality? Is the personality of each individual unique or are there broad personality patterns that fit large numbers of persons? 5. Equilibrium or growth? Are we primarily tension-reducing, pleasure-seeking animals or are we motivated primarily by the need to grow, to reach our full potential to reach for ever-higher levels of selfexpression and development? 6. Optimism or pessimism? Are human beings basically good or evil? Are we kind and compassionate, or cruel and merciless? THE PSYCHOANALYTIC PERSPECTIVE Freud found that nervous disorders often made no neurological sense. He began to hypnotize his patients, encouraging them to talk freely about the circumstances surrounding the onset of their symptoms. As they did so, their symptoms often diminished or even disappeared. Freud concluded that emotional disorders resulted from the unconscious dynamics of personality. Recognizing patients’ uneven capacity for hypnosis, Freud turned to free association, which he believed produced a chain of thoughts in the patient’s unconsciousness. He called the process psychoanalysis. Freud believed the mind is like an iceberg --- mostly hidden, with the unconscious containing thoughts and memories of which we are largely unaware. Some of these thoughts we store temporarily in a preconscious area. Freud believed that personality arises from our efforts to resolve the conflict between our biological impulses and the social restraints against them. He theorized that the conflict centers on three interacting systems: the id, which operates on the pleasure principle, and the ego, which functions on the reality principle, and the superego, an internalized set of ideals. Freud maintained that children pass through a series of psychosexual stages during which the id’s pleasure-seeking energies focus on distinct pleasuresensitive areas of the body called “erogenous zones”. During the oral stage (0-18 months) pleasure centers on the mouth. During the anal stage (18-36 months) pleasure centers on bowel/bladder elimination. During the critical phallic stage (3-6 years), pleasure centers on the genitals. Boys experience the Oedipus complex, which unconscious sexual desires toward their mother and hatred of their father. They cope with these threatening feelings through identification with their father, thereby incorporating many of his values and developing a sense of gender identity. The latency stage (6 years to puberty), in which sexuality is dormant, gives way to the genital stage (puberty on) as youths begin to experience sexual feelings toward others. In Freud’s view, maladaptive adult behavior results from conflicts unresolved during the oral, anal, and phallic stages. At any point, conflict can occur, or fixate, the person’s pleasure-seeking energies in that stage. Defense mechanisms reduce or redirect anxiety in various ways, but always by distorting reality. For example ** Repression, which underlies the other defense mechanisms, banishes anxietyarousing thoughts from consciousness. Regression involves retreat to an earlier, more infantile stage of development. Reaction formation makes unacceptable impulses look like their opposites. Projection attributes threatening impulses to others. Rationalization offers self-justifying explanations for behavior. Displacement divert impulses to a more acceptable object. Sublimation is the transformation of unacceptable impulses into socially valued motivations. On a projective test, such as the Thematic Apperception Test (TAT) and Rorschach inkblot test, people are provided with an ambiguous stimulus and then asked to describe it or tell a story. The stimulus has no inherent meaning, so whatever meaning people read into it presumably reflects their interests and conflicts. Although projective tests have questionable reliability or validity, many clinicians continue to use them. In contrast to Freud, the neo-Freudians generally placed more emphasis on the conscious mind in interpreting experience and coping with the environment, and they argued that we have more positive motives than sex and aggression. Unlike other neo-Freudians, Carl Jung agreed with Freud that the unconscious exerts a powerful influence. In addition, he suggested that the collective unconscious is a shared, inherited reservoir of memory traces from our species’ history. Critics contend that many of Freud’s specific ideas are implausible, unvalidated, or contradicted by new research, and that his theory offers only afterthe-fact explanations (not to mention misunderstanding women and children!!!). Many researchers now believe that repression rarely, if ever occurs. Nevertheless, Freud drew psychology’s attention to the unconscious, to the struggle to cope with anxiety and sexuality, to the conflict between biological impulses and social restraints, and to the importance of childhood. His cultural impact has been enormous. THE TRAIT PERSPECTIVE Some psychologists attempt to describe and classify personalities in terms of traits. Sheldon classified people by body type: as endomorph, mesomorph, or ectomorph. More popular today is an effort to classify people according to Carl Jung’s personality types Through factor analysis, Hans and Sybil Eysenck reduced normal variations to two or three genetically influenced dimensions, including extraversion-introversion and emotional stability-instability. More recently, researchers have isolated five distinct personality dimensions, dubbed the Big Five: emotional stability, extraversion, openness, agreeableness, and conscientiousness. Genetic predispositions influence most such traits. ** Psychologists assess several traits at once by administering personality inventories. For example, the empirically derived Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory (MMPI-2) was originally developed to identify the traits of emotionally troubled people. Although people’s traits seem to persist over time, human behavior varies widely from situation to situation. Despite these variations, a person’s average behavior across different situations is fairly consistent. Moreover, individual differences in some traits, such as expressiveness, can be quickly perceived. THE HUMANISTIC PERSPECTIVE Maslow believed that if basic human needs are fulfilled and self-esteem is achieved, people will strive to actualize their highest potential. To describe selfactualization, he studied some exemplary personalities and summarized his impression of their qualities. To nurture growth in others, Rogers advised being genuine, empathic, and accepting (offering unconditional positive regard). In such a climate, people can develop a deeper self-awareness and a more realistic and positive selfconcept. Humanistic psychologists assess personality through questionnaires on which people report their self-concept and by seeking to understand others’ subjective personal experiences in therapy. People who have high self-esteem have fewer ulcers, are less likely to use drugs, are less conforming, are more persistent at difficult tasks, are more accepting of others, and are just plain happier. Self-serving bias, our readiness to perceive ourselves favorably, can lead to excessive pride and self-righteousness. The self-serving perceptions that underlie conflicts range from other-blaming marital discord to self-promoting ethnic snobbery. Self-reliant individualists define identity in terms of personal goals and individual achievement. Being self-contained, they easily move in and out of groups. Socially connected collectivists give priority to group goals and to their social identities and commitments. Because they value communal solidarity, they place a premium on maintaining harmony and allowing others to save face. People in competitive, individualistic cultures have more personal freedom, take more pride in personal achievements, are less geographically bound to their families, and enjoy more privacy. But these benefits come at the cost of more frequent loneliness, more divorce, more homicide, and more stress-related disease. Critics complain that the perspective’s concepts are vague and subjective. For example, the description of self-actualizing people seems more a reflection of Maslow’s personal values that a scientific description. The individualism promoted by humanistic psychology may promote selfindulgence, selfishness, and an erosion of moral restraints. Furthermore, humanistic psychology fails to appreciate the reality of our human capacity for evil. Its naïve optimism may lead to apathy about major social problems. THE SOCIAL-COGNITIVE PERSPECTIVE The social-cognitive perspective applies principles of learning, cognition, and social behavior to personality, with particular emphasis on the ways in which our personalities influence and are influenced by our interaction with the environment. It assumes reciprocal determinism --- that personal-cognitive factors combine with the environment to influence behavior. People who perceive an internal rather than an external sense of locus of control achieve more in school, are more independent, and are less depressed. Moreover, they are better able to delay gratification and cope with various stresses. Faced with repeated traumatic events over which they have no control, people come to feel helpless, hopeless, and depressed. Their learned helplessness may result in passivity in later situations where their efforts could make a difference. Those who see setbacks as flukes rather than as signs of incompetence are likely to be more persistent and successful. Optimists have also been found to outlive pessimists, as well as to have fewer illnesses. Excessive optimism, however, can lead to complacency and can blind us to real risks. The study of personal control and optimism reflects the new interest in positive psychology, the scientific study of optimal human functioning. Social-cognitive researchers observe how people’s behaviors and beliefs both affect and are affected by their situations. They have found that the best way to predict someone’s behavior in a given situation is to observe that person’s behavior pattern in similar situations. Although faulted for slighting the importance of unconscious dynamics and inner traits, the social-cognitive perspective builds on psychology’s wellestablished concepts of learning and cognition and reminds us of the power of social situations.