essay1 - The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill

advertisement

“Indefinable Islamic Culture”

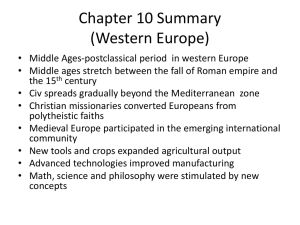

It is a common misconception that “the west” or western civilization is in opposition with

the “the Muslim world”(Ernst [2004]:3). Universal acceptance of this false assumption sets the

stage for the over simplification of Islamic culture through broad assertions that stereotype the

Muslim people. In an attempt to draw a definite box around everything that can be considered

part of “Islamic culture,” a person neglects to realize the complexity of a culture and imposes

unnatural divisions to define Islamic culture such that it is simple, limited but also often

incorrect. To look at Islamic culture as it truly exists, requires an acknowledgement of culture, as

something which cannot exist in isolation. Islamic culture does not exist in a “pure” form in

which it is free from any outside influence. But the overwhelming number of influences and

contributions that make up various cultures make it difficult to determine where to draw the line

between that which belongs to Islamic culture and that which does not. Infinite and ongoing

interactions between cultures leave a vast grey area in which association with Islamic culture is

debatable and open to interpretation. The distinction between Islamic art and Islamicate,

acknowledges the problematic task of understanding culture in the absence of definite

boundaries. Although Islamic civilization is clearly associated with Islamic religion, Islamicate

recognizes the significance of secular influences and the participation of non-Muslims in Islamic

culture (Ernst [2004]: 184). Islamicate is not only important to identify in architecture and art;

Islamic culture has been largely shaped by non-secular forces. Distinctions between Islamic art

and Islamicate highlight the ambiguous boundaries of religious identity that make Islamic culture

complex. Political structures arising from Qur’anic principles suggest that the most basic Muslim

beliefs encourage the development of an integrated society, creating questions as to the scope of

Islamic religion. Cultures constantly borrowing and sharing ideas and traditions result in messy

1

overlaps; specifically in art and philosophy. The distinction between Islamic art and Islamicate,

applied to Islamic culture, brings to light the role of religion in Islamic civilization and the

problematic questions that make it difficult to define Islamic cultures.

The Muslim authority’s recognition of multiple religious groups in the Arab Empire, set

the stage for ambiguity surrounding that which qualifies as Islamic culture. By incorporating

religions other than Islam in the political system, it guaranteed the influence of non-Muslims

within Islamic culture. Individuals of a society largely direct cultural development; it is unclear

how to identify characteristics of a religious culture that is largely made up of non-Muslims. This

is the question that Islamicate attempts to clarify by acknowledging the absence of Islamic

religion in numerous aspects of Islamic culture. While the political policy of religious pluralism

suggests Islamicate is a legitimate form of Islamic culture, this institutional incorporation of

multiple religions is derived from Qur’anic scripture. The Qur’an refers to “People of the Book,”

as people who practice a religion that contains a sacred text. According to the Qur’an, people

practicing these religions are spiritual kinsmen to the Muslim people and should be allowed to

practice their religion (Egger [2003]: 29). In accordance with this passage from the Qur’an, the

Arab Empire adopts a policy of religious pluralism. The Arabs set-up a taxation system in which

non-Muslims can practice their own religions under the protection of Muslim authorities in

return for a tax; these people became known as dhimmis (Egger [2003]: 48). This political

structure derived from Holy Scripture lays the foundation for ambiguous boundaries regarding

identity and overlap between cultures; both of which are addressed by the concept of Islamicate.

From the very beginning, Islamic culture does not exist in the “pure” form that people constantly

attempt to reduce it to. Even within their own empire, Muslims were initially a minority; Islamic

civilization as it originated in the Arab empire, began with a society in which the majority of the

2

people had no connection to Islamic religious beliefs {Egger [2003]: 48). Early integration of

multiple religious groups makes it difficult to define the scope of that which qualifies as part of

Islamic civilization.

Architectural structures and art forms typically associated with Islamic culture have

historically been employed by non-Islamic cultures. In India during the fifteenth century, a

manual was written in Sanskrit providing directions on how to build a mosque. The temple, it

was written, was to be dedicated to a formless supreme God was not to include any images; these

principles clearly correlate with Islamic principles (Ernst [2004]: 188). This presence of Islamic

culture in Indian culture is commonplace. Cultures are constantly borrowing ideas and traditions

from Islamic culture (and other cultures they may have contact with) to enhance their own

culture. These overlaps that then occur make it increasingly difficult to distinguish architecture in

Islamic culture from architecture in India. Is the dome a feature of Islamic culture or Indian

culture? Islamicate recognizes the presence of non-Muslims, and their contributions to Islamic

culture. The presence of Islamic art can be seen in the palace constructed under the Spanish

Christian King Pedro. The king employed Moors from Granada to construct a palace in Seville.

The palace was covered with arabesque design and Arabic calligraphy, both art forms associated

with Islamic culture. The art had no religious significance to the king, but was instead used to

signify imperial authority (Ernst [2004]:188). Again, cultures overlap, and the lack of religious

meaning comes into question. During this time, Christians were conflicted about Islamic faith.

However, they continued their appropriation of Islamicate culture, which came to be known as

mudajar art (Ernst [2004]:189). These various cases are examples of the constant intersections

between Islamic culture and other cultures, which make the task distinguishing Islamic culture

from other cultures difficult. It further reinforces inaccuracy of the universally held belief, that

3

the Muslim world is in some way separated from the rest of civilization and therefore exists in

some “pure” form. Not only is it difficult to pin point that which is considered part of Islamic

culture, but it is made even more complex in that Islamic culture is not defined by Islamic

religion. Issues highlighted by the definition of Islamicate are seen in art and architecture in

context of Islamic religion.

Like Islamic art and architecture, Islamic philosophy is not associated exclusively with

Islamic civilization. While art forms typically associated with Islamic culture could be found in

the art and architecture of other cultures, Muslims borrowed philosophical thought from Greek

culture (Egger [2003]:130). Muslims exposure to Greek philosophy began with the establishment

of The House of Wisdom, Bayt al-Hikma. The library was central to Al-Ma’mun’s effort to

institutionalize the translation process. The project resulted in the translation of many Greek

manuscripts that became available in Arabic (Egger [2003]:129). The philosophical works of

Plato and Aristotle quickly became popular among Muslim scholars, who called themselves

philosopher-scientists, like their Greek predecessors (Egger [2003]:131). While diverse

philosophical thought emerged, Greek works remained the foundation of Islamic philosophy.

Philosopher-scientists explored the relationship between philosophy and religion, and used

reason to evaluate philosophy as opposed to looking to “authority as the standard of justice and

right behavior”(Egger [2003]:121). The work of Prime Minister Davani, in Jalalian Ethics, is a

good example of the way in which Islamic philosophy integrates Greek philosophical

perspectives with religious values central to Islam (Ernst [2004]:122). It is impossible to separate

Islamic philosophical tradition from Greek ideas, and therefore it is impossible to separate from

western civilization. But because development of Islamic philosophy was largely connected to

Greek ideas, it appears that contributions made by Muslims have been largely overlooked.

4

Historical accounts presented by western civilization emphasize the decline in civilization

following the contributions of Plato and Aristotle, and the reemergence upon the arrival of

European colonialism (Ernst [2004]:124). It is possible that philosophy as it pertains to Islamic

culture is generally neglected as a result of the European agenda to portray their culture as

superior. But as the concept of Islamicate points out, the difficulty in definitive cultural

boundaries leaves cultural definitions up to interpretation. In this instance, the integration of two

cultures, and the inability of Muslims to claim exclusive ownership to their own philosophical

thought, may have allowed for Eurocentric based history to overlook their contributions and

focus solely on the contributions made by ancient Greek culture.

The difficulty of defining what traditions, ideas and beliefs lay within the scope of a

culture is evident from the distinction between Islamic art and Islamicate. Issues surrounding

intersections between cultures and the significance of religion in identifying that which qualifies

as part of a specific civilization, make it difficult to determine the scope of Islamic culture. This

is true of many cultures, but it is particularly harmful within the context of Islamic culture

because of the prevalent belief that the Muslim world is separate from Western civilization. If

one fails to acknowledge the legitimate implications of Islamicate, it is likely to result in extreme

stereotyping and ignorance and a never ending search for an isolated form of Islamic culture. It is

clear that Islamic culture, in terms of political structures, art and philosophy cannot be

understood as isolated subjects.

Bibliography

Egger, Vernon. A History of the Muslim World To 1405 : The Making of a Civilization. Upper

Saddle River: Prentice Hall, 2003.

5

Ernst, Carl. Following Muhammad. New York: University of North Carolina P, 2004.

6