Summary of:

Dixson, A., Dixson, B., & Anderson, M. (2005). Sexual selection and the evolution of visually

conspicuous sexually dimorphic traits in male monkeys, apes, and human beings. Annual

Review of Sex Research,16, 1-19.

Summary by: Stefanie Galich, Megan Dorrian, and Sean Ivester

For Dr. Mills’ Psychology 310 class, Fall, 2007

According to the Darwinian view of sexual selection, traits that enhance reproductive

success are selected during the course of evolution. This is true especially in males and includes

sexually attractive traits such as adornments, horns, antlers, enlarged canine teeth and other

physical weapons that improve fighting capabilities. Experiments have shown that these

conspicuous adornments seem to influence female choice and improve mating and reproductive

success of males. This article suggests that although male weaponry may have evolved from

intrasexual selection, it is possible that the masculine features provide information to females

regarding the reproductive condition of particular males.

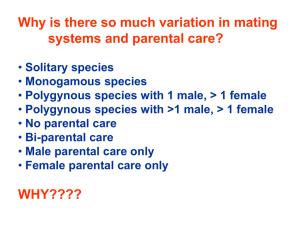

Among primates, pronounced sex differences in body size and canine teeth size are

eminent, with the most impressive differences among those species with polygynous or

multimale-multifemale mating systems. However, the possible functions of these male

adornments, whether to enhance sexual attractiveness or intimidate competitive males, have been

poorly studied among primates.

This review focuses on the relationships between occurrences of sexually dimorphic

visual traits in male anthropoids (i.e., monkeys, apes, and human beings) and the types of mating

systems (monogamous, polygynous, or multimale-multifemale) that characterize the various

species and genera. Sex differences regarding body weight and development of masculine

secondary sexual traits are compared to test whether there is a correlation between increased

body size and occurrences of visual adornments in adult males. One difficulty faced in

undertaking this task is the lack of quantitative measures of sexually dimorphic visual traits in

primates. The article first describes the methodology used to quantify these sex differences.

Secondary Sexual Traits in Male Primates: A Quantitative Approach

Many of the second sexual characteristics that are visually distinctive and sexually

dimorphic in primates are often difficult to measure quantitatively. This might be the reason why

most researchers have concentrated on sexual dimorphisms in more readily available features,

such as body weight or canine tooth size. For other traits such as capes of hair, beard, crests, it

would be advantageous to obtain exact measures of length and color for all species that sexual

dimorphisms occur. However, such approaches have rarely been attempted. If quantification and

statistical comparisons are going to be produced, a strategy is required to quantify visual traits

across a range of species. The approach adopted in this article was to score each sexually

dimorphic visual trait on a 6-point rating scale, ranging from 0 (no difference occurs between

males and females) up to 5 (maximum dimorphism, with males possessing a prominent visual

trait absent in females). Ratings were made of all sexually dimorphic visual traits involving the

trunk, limbs, and head for a total of 124 species representing 38 different genera of New World

monkeys, Old World monkeys and apes, and Homo sapiens.

Sexual Dimorphism in Visual Traits and Primate Mating Systems

The visual trait scores for adult male primates were analyzed according to their principal

mating systems. Polygyny was found to be associated with significantly higher ratings for

masculine visual traits across the genera and species analyzed. Overall, the order of visual trait

development (highest to lowest) is polygyny > monogamy > multimale-multifemale. Multimalemultifemale forms have very low ratings for male-biased sexual dimorphism in visual traits.

Visual traits are also poorly developed in males of most monogamous primate species, with only

a few notable exceptions. Therefore, the human male is not unique among primates that have

monogamous mating systems.

Exceptional Cases: The Mandrill and the Orang-Utan

Two genera are not included in the above analysis because authorities differ as to how

their mating systems should be classified. These are Mandrillus (the mandrill and drill) and

Pongo (the orang-utan of Borneo and Sumatra). The adult male mandrill is the most brightly

colored mammal that exists. In the closely related drill, adult males have a less colorful (black)

face and many visual adornments. Their social groups may fragment into smaller units

traditionally assumed to be polygynous, one-male units. However, observations on semifreeranging mandrill indicate that they have a multimale-multifemale mating system and large

relative testes size.

Orang-Utans are the only anthropoid primates that do not form permanent social groups.

Males are assumed to be nongregarious and occupy large home ranges, which overlap several

smaller individual home ranges of females. Relatively slow moving orang-utans have a dispersed

social organization, in which females may approach and consort with fully developed adult

males. Nonterrirotiral males, with less well-developed secondary sexual characteristics, may

pursue females and attempt to mate with them. The extreme sexual dimorphism and striking

adornments of the male orang-utan may have been selected, due to its nongregarious social

organization and mating system. It is also possible that abnormal selection pressures have

molded the secondary sexual adornments of the adult male orang-utan. Fully developed males

are highly aggressive towards each other and employ distance displays for communication in the

rainforest. Dominant males are known to suppress secondary sexual development in subordinate

male orang-utans. Suppression of secondary sexual development also occurs in subordinate male

mandrills. The gain and loss of alpha status among males is associated with changes in males’

adornments.

Secondary Sexual Visual Traits in the Human Male: Comparative Perspectives

Scores for sexually dimorphic visual traits in males are positively correlated with the

degree of sexual dimorphism in body weight. This correlation is mainly due to the genera that

have polgynous mating systems. The genus Homo is characterized by low sexual dimorphism in

body weight, accompanied by a relatively high score for masculine visual traits. The sexually

dimorphic visual traits of human males are not incompatible with the designation of monogamy

as the principal mating system. However, polygyny also occurs in many human cultures, usually

as an exclusive privilege to men of higher social status. Therefore, the evolution of conspicuous

adornments in human males may have occurred within this context. However, there were several

conditions that undercut this view. First, sexual dimorphism in body size in very low in Homo

compared with polynous primates. Moreover, the canine teeth of all human beings are small and

men lack enlarged canines that are typical of polygynous monkeys and apes. Finally, the human

male has relatively small testes in relation to body weight. Testes weights in men are comparable

to those of nonhuman primates that are monogamous – or polygynous – and that have low levels

of sperm competition. Other comparative studies of other reproductive traits also indicate that the

evolution of human sexual behavior is unlikely to have involved strong selection via sperm

competition.

Sexual selection involves attractiveness to the opposite sex. Even though the two sexes

are similar in size in Homo sapiens, men are somewhat larger, more muscular, and considerably

stronger than women. Women on the other hand, have a higher proportion of body fat than men.

This optimal distribution of body fat may be associated with a low waist-to-hip ratio and a

curvaceous shape not only attractive to men but also a signal of female and health and

reproductive potential. Some have seriously challenged the waist-to-hip ratio hypothesis though,

and limited evidence shows that such a waist-to-hip ratio may be universally disfavored by men.

Some evidence indicates that weight scaled for height may provide a better measure of female

attractiveness. In the remainder of the article, the authors consider some of the evidence

concerning the evolution of physique and visual traits in the human male and ask whether sexual

selection and female mate choice have played a significant role in this process.

Somatotype, Secondary Sexual Traits, and Attractiveness in the Human Male

It is very likely that numerous features influence sexual attractiveness in human beings,

as in many other animals too. A male muscular torso with broad shoulders and a narrow waist

are rated as more attractive by some women in past studies. A cross-cultural study involving

subjects in the U.K. and Sri Lanka had women rate back-posed images of the following men:

mesomorphic (muscular), average, ectomorphic (slim), and endomorphic (heavily built).

Mesomorphic images were rated as most attractive and endomorphic images as least attractive.

These results are consistent with the theory that sexual selection has an effect on visual

signals, which advertise masculine strength, physical health, age, and endocrine condition in the

human male. Early in evolution, a mesomorphic male may have offered greater protection for a

female and possessed physical advantages in hunting. Currently, we know very little about the

distinct selective forces that molded the evolution of visual traits in human beings. Very few

cross-cultural studies have been executed that measure women’s ratings of masculine traits in

different human populations.

Conclusion

Among nonhuman primates, masculine secondary sexual adornments are greatest in those

species having polgynous mating systems. Adult males in polygynous systems show

significantly higher scores for combination of visual traits than those monkeys and apes in

monogamous or multimale-multifemale groups. Males of polygynous primate species also tend

to be much larger than females, and the sexual dimorphism of body weight correlates with scores

for masculine visual traits. Monogamous monkeys and apes sometimes have high scores for

visual adornments, but these traits are not as pronounced as for polygynous species. Human

males also show sexually dimorphic visual traits in the absence of sexual dimorphism of body

weight. The visual traits of human males are consistent with those of primates in which pairformation, monogamy, and small family groups are the basic mating systems. Quantitative crosscultural studies of the functions of visual traits and secondary sexual adornments in human

males, and their roles in sexual attractiveness and intermale status are very limited.

OUTLINE

I) Secondary sexual traits in male primates

A) Quantitative approach

B) Six point rating scale of sexually dimorphic visual traits

1) Zero= no difference occurs between males and females

2) Five= maximum dimorphism, with males possessing a prominent visual trait absent,

or nearly absent in females

II) Sexual dimorphism in visual traits and primate mating systems

A) Human mating systems are primarily monogamous, but sometimes polygynous

1) Polygyny occurs among higher status males with power, wealth and resources

2) Both types occur cross-culturally among Homo sapiens

3) Polygyny is associated with higher ratings for masculine visual traits across genera

and species

B) Monogamous primates exhibit significantly higher scores for sexual dimorphism in visual

traits than multimale-multifemale species

C) Visual trait development is highest in polygyny, then monogamy and lowest in

multimale-mulitfemale species

1) The human male is not unique among primates that have monogamous mating

systems in regards to the development of masculine secondary sexual visual traits

III) Exceptional cases

A) Mandrill:

1) Polygynous or multimale-mulitfemale mating systems

2) Engage in mate guarding of females

3) Extreme sexual dimorphism: brightest coloration of adult male mammals

(a) Evolved due to an enhanced need for competitive signals due to no long term

social bonds between breeding partners and extreme selection pressure for them

to signal rank to other males and/or their attractiveness to females

4) Dominant males suppress secondary sexual development in subordinate males

B) Orang-Utan:

1) Only anthropoid primates that do not form permanent social groups

2) Fully adult males are highly aggressive towards each other

3) Extreme sexual dimorphism: adornments

4) Dominant males suppress secondary sexual development in subordinate males

(a) Alternate reproductive strategy

(b) Gain and loss of alpha status is associated with changes in the male’s adornments

IV) Secondary sexual visual traits in the human male

A) Conspicuous visual traits of adult human male

1) Scores for sexually dimorphic visual traits in males are positively correlated with the

degree of sexual dimorphism in body weight, highly correlated to genera of

polygynous mating systems

(a) Body weight ratio

(b) The genus Homo has low sexual dimorphism in body weight and a high score for

masculine visual traits

2) Polygyny occurs in many human cultures, usually among men of higher social status

or greater resources

3) Sexual dimorphism in body size is very low in Homo sapiens

4) Canine teeth of all humans are small

5) Human males have relatively small testes in relation to body weight

(a) Evolution of human sexual behavior is unlikely to have involved strong selection

via sperm competition

B) Sexual selection involves the attractiveness of the opposite sex

1) Two sexes are of similar size in Homo sapiens

(a) But, men are somewhat larger, more muscular, and stronger than women

(b) Women have a higher percentage of body fat

2) Low waist-to-hip ratio may be optimal and illustrate health and reproductive potential

of females

(a) In contrast, the 0.7 ratio may not be universally favored by men

3) Weight scaled for height (body mass index) may provide a more relevant measure of

female attractiveness

V) Somatotype, secondary sexual traits, and attractiveness in the human male

A) Tall men have greater reproductive success

B) Muscular torso, broad shoulder, narrow waist and a deep masculine tone of voice are

rated attractive by some women

C) In a study in UK and Sri Lanka, mesomorphic males are rated as most attractive by

females

D) Sexual selection has an effect on visual signals advertising masculine strength, physical

health, age and underlying endocrine condition in the human male

1) Mesomorphy may be an indicator of superior cardiac function and metabolic health

(a) May have offered a female greater protection and possessed physical advantages

in hunting

2) Endomorphy has been correlated with greater risk of heart disease and poor general

health

3) Mesomorphic and endomorphic figures were found to be more attractive with trunk

hair

VI) Conclusion

A) Among nonhuman primates, masculine secondary sexual adornment are greatest in

polygynous species

1) These males tend to be much larger than females

2) The degree of sexual dimorphism in body weight correlates significantly with scores

for masculine visual traits

B) Among monogamous monkeys and apes, adult males have high scores for visual

adornments, which are not as pronounces for polygynous species

C) Human males exhibit sexually dimorphic visual traits in the absence of pronounced

sexual dimorphism in body weight

TEST QUESTIONS:

1. What mating system has the highest level of visual trait development? A…

a. Monogamous mating system

b. Polygynous mating system

c. Multimale-multifemale mating system

d. Poyandrous mating system

2. What are two main purposes for why sexual dimorphic traits evolve?

a. Selection pressures for males to signal rank to other males AND to signal their

attractiveness to other females

b. Competitive signals AND mate guarding

c. Reproductive awards AND attractiveness to the opposite sex

3. Which somatotype tends to be preferred by women for men?

a. endomorph

b. mesomorph

c. ectomorph

4. T/F: Size of canine teeth and body are two major differences we discussed between

humans and non-human primates in regards to sex differences.

3. T/F: Males of polygynous primate species tend to be much larger than females.

5. T/F: Primarily monogamous species have low sexual dimorphism and body weight.

ANSWERS:

1. b

2. a

3. b

4. T

5. T

6. T