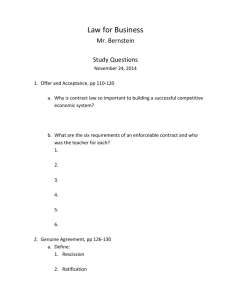

Chapter 2 - The Classical System of Contract Law: Mutual Assent

advertisement