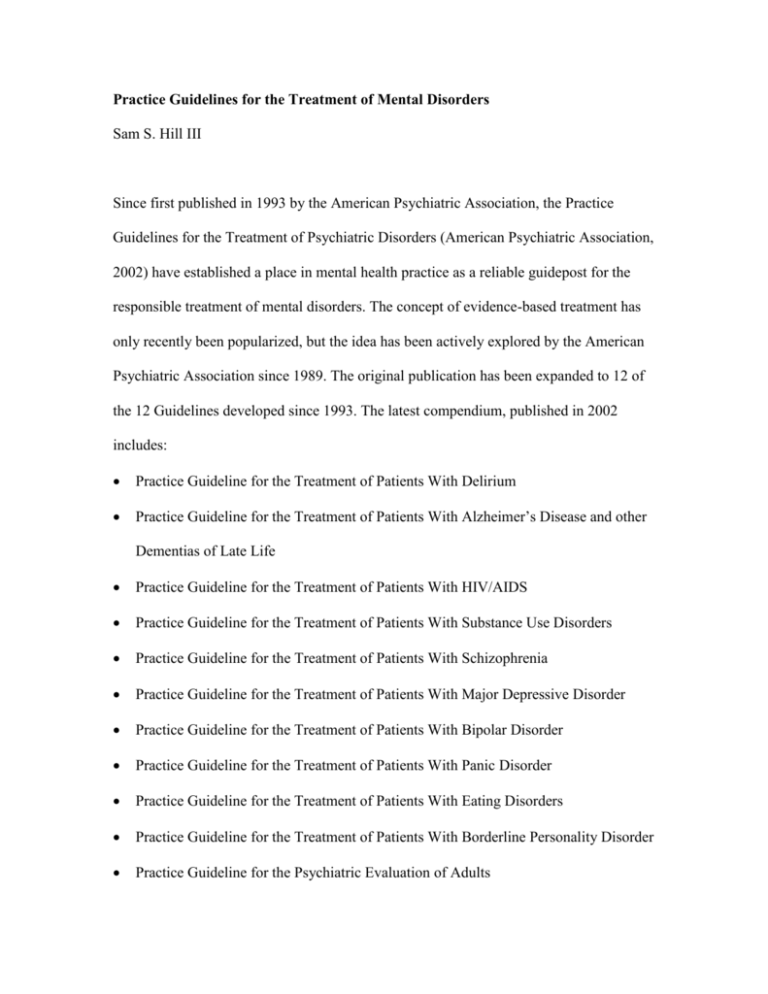

Practice Guidelines for the Treatment of Mental Disorders

advertisement

Practice Guidelines for the Treatment of Mental Disorders Sam S. Hill III Since first published in 1993 by the American Psychiatric Association, the Practice Guidelines for the Treatment of Psychiatric Disorders (American Psychiatric Association, 2002) have established a place in mental health practice as a reliable guidepost for the responsible treatment of mental disorders. The concept of evidence-based treatment has only recently been popularized, but the idea has been actively explored by the American Psychiatric Association since 1989. The original publication has been expanded to 12 of the 12 Guidelines developed since 1993. The latest compendium, published in 2002 includes: Practice Guideline for the Treatment of Patients With Delirium Practice Guideline for the Treatment of Patients With Alzheimer’s Disease and other Dementias of Late Life Practice Guideline for the Treatment of Patients With HIV/AIDS Practice Guideline for the Treatment of Patients With Substance Use Disorders Practice Guideline for the Treatment of Patients With Schizophrenia Practice Guideline for the Treatment of Patients With Major Depressive Disorder Practice Guideline for the Treatment of Patients With Bipolar Disorder Practice Guideline for the Treatment of Patients With Panic Disorder Practice Guideline for the Treatment of Patients With Eating Disorders Practice Guideline for the Treatment of Patients With Borderline Personality Disorder Practice Guideline for the Psychiatric Evaluation of Adults Practice Guideline Development Process The guidelines are organized into a single volume available in paper binding or hardbound. There is a smaller, more portable Quick Reference that summarizes the most important elements of the larger volume. The new edition makes use of the analog decision schematics that are found in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, rev. 4th edition (DSM-IV-TR). Each practice guideline was reviewed by an impressive list of prominent individuals and institutions nationally and internationally known for their expertise in the particular disorder they reviewed. The Guidelines were written by psychiatrists but hold a wealth of information for practitioners from any of the mental health professions. The Guidelines are presented in a common format. The exceptions to this commonality are the specific requirements of the disorders they address. The first part of the Guideline deals with treatment recommendations. This section presents a subsection that summarizes the current state of the art in treatment recommendations. The next subsection suggest the process for formulating and putting into effect a treatment plan, and the concluding subsection of the first section examines specific clinical features that impact the treatment plan. The second section gives a history of the disorder and reviews the current state of science in the disorder. The first subsection defines the disorder, referred to as the “disease,” presents its Epidemiology, Natural History, and Course. The second subsection of the second section reviews and synthesizes the available evidence on the disorder. The third and final section discusses future research needs in the disorder. In the introduction to the Guidelines the American Psychiatric Association laments the low utilization of the Guidelines by their membership but emphasizes the importance of education and dissemination of the practice guidelines and has made this a primary goal for that organization in the future. The non-physician will find the guidelines to be a useful reference resource. Each of the Guidelines concludes with a lengthy reference list of the latest and most important research in the specific disorder addressed by the Guideline. While the approach to treatment in the Guidelines strongly emphasizes the biological aspects of treatment there is an overall endorsement of the Biopsychosocial approach to treatment in what is sometimes referred to as a “whole patient” approach to treatment. There is a wealth of information on differential diagnosis and the treatments guidelines give ample information for those whose approach may be more one of prescriptive eclecticism. There is broader acceptance of these treatment guidelines among third party payers when reviewing treatment plans and progress reports. There is general need expressed by managed mental health groups for specific treatment criteria to which they can hold clinicians in determining whether they are going to provide payment for a course of treatment. Myriad issues are associated with the desirability of treatment guidelines, and there are good reasons why many professional associations have not published treatment guidelines. However, the financial realities of the current treatment environment make the use of treatment guideline at least useful. Organization of the Treatment Guidelines The guidelines are organized into a single volume available in paperback. The volume contains the not only the treatment guidelines but a chapter dealing with important considerations in conducting a psychiatric/psychological evaluation. The sections of this chapter include guidance on formulating the referral question to be answered in the evaluation. Another section deals with the influence of the clinical setting of the evaluation interview. The chapter then deals with the domains of the clinical evaluation and finally the process of evaluation. The chapters are composed with the treatment imperatives of each disorder taking precedence over organization uniformity. The first three section of each treatment guideline begins with: A summary of recommendations A disease definition, epidemiology, and natural history Treatment principles and alternatives The formulation and implementation of a treatment plan Clinical features influencing treatment A listing of the reviewers and reviewing organizations A reference list The essential content of the chapters remains as in previous editions of the treatment guidelines with elaboration of specific treatment regimens, specifically I the guideline for the treatment of HIV/AIDS. Example of a Treatment Guideline: “Treatment guidelines for the treatment of patients With HIV/AIDS” The guideline is presented in two parts o Part A: Background Information and Treatment Recommendations for Patients With HIV/AIDS o Part B: Review and Synthesis of Available Evidence Part A includes the summary of treatment recommendations, disease definition, epidemiology and natural history, the formulation and implementation of the treatment plan, and the clinical and environmental features influencing treatment. Part B reviews the data regarding the prevention for individuals at high risk for HIV infection and data regarding the psychiatric treatments for individuals with HIV infection. Psychotherapy is given equal footing with pharmacotherapy interventions and the emphasis on the “total person” and his or her living environment is enough to warm the heart of any clinical social worker. The Quick Reference to the American Psychiatric Association Practice Guidelines for the Treatment of Psychiatric Disorders Compendium 2002 was published to meet the needs of the practicing professional. Although this writer did not measure the volume, it appears to be just about the size of the waist pocket of the white physician’s coat. The quick reference “cuts to the chase” the ten disorders considered. The 10 quick reference guides (QRGs) are condensed, but complete versions of the original treatment guidelines found in the large volume. The obvious challenge was to write the QRGs in enough detail to be useful but brief enough to be truly portable. The organization of the QRGs is in 4 sections, including diagnosis and assessment, and treatment recommendations vary according to the evidence-based treatment indicated. This is what Norcross and Prochaska among others have called prescriptive eclecticism, (Norcross & Prochaska, 1988). The heavy emphasis on sequence of treatment and pharmacotherapy make the quick reference less useful to the non-physician clinician. It should be kept in mind that the quick reference was written for the practicing psychiatrist and the logic and process is geared to those professions treatment concepts. References and Readings American Psychiatric Association (2002). Practice guidelines for the treatment of psychiatric disorders: compendium 2002. Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Press American Psychiatric Association (2002). Quick reference to the American Psychiatric Associations practice guidelines for the treatment of psychiatric disorders: compendium 2002. Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Press Norcross, J. C., & Prochaska, J. O. (1988). A study of eclectic (and integrative) views revisited. Professional Psychology: Research & Practice, 19, 170–174.